Abstract

Introduction

To investigate the association of individual and contextual exposures with lung function by gender in rural-dwelling Canadians.

Methods

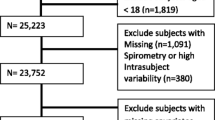

A cross-sectional mail survey obtained completed questionnaires on exposures from 8263 individuals; a sub-sample of 1609 individuals (762 men, 847 women) additionally participated in clinical lung function testing. The three dependent variables were forced expired volume in one second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), and FEV1/FVC ratio. Independent variables included smoking, waist circumference, body mass index, indoor household exposures (secondhand smoke, dampness, mold, musty odor), occupational exposures (grain dust, pesticides, livestock, farm residence), and socioeconomic status. The primary analysis was multiple linear regression, conducted separately for each outcome. The potential modifying influence of gender was tested in multivariable models using product terms between gender and each independent variable.

Results

High-risk waist circumference was related to reduced FVC and FEV1 for both genders, but the effect was more pronounced in men. Greater pack-years smoking was associated with lower lung function values. Exposure to household smoke was related to reduced FEV1, and exposure to livestock, with increased FEV1. Lower income adequacy was associated with reduced FVC and FEV1.

Conclusion

High-risk waist circumference was more strongly associated with reduced lung function in men than women. Longitudinal research combined with rigorous exposure assessment is needed to clarify how sex and gender interact to impact lung function in rural populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For brevity sake, we use the term gender throughout the rest of the paper; however, we recognize that the effects of sex and gender on human health are complexly interwoven throughout the life course [19].

References

Kannel W, Hubert H, Lew E (1983) Vital capacity as a predictor of cardiovascular disease: the framingham study. Am Heart J 105:311–315

Mannino D, Buist A, Petty T et al (2003) Lung function and mortality in the United States: data from the first national health and nutrition examination survey follow-up study. Thorax 58(5):388–393

Canoy D, Pekkanen J, Elliott P et al (2007) Early growth and adult respiratory function in men and women followed from the fetal period to adulthood. Thorax 62(5):396–402

Mirabelli MC, Preisser JS, Loehr LR et al (2016) Lung function decline over 25 years of follow-up among black and white adults in the ARIC study cohort. Respir Med 113:57–64

Eisner MD, Wang Y, Haight TJ et al (2007) Secondhand smoke exposure, pulmonary function, and cardiovascular mortality. Ann Epidemiol 17(5):364–373

Canoy D, Luben R, Welch A et al (2004) Abdominal obesity and respiratory function in men and women in the EPIC-norfolk study, United Kingdom. Am J Epidemiol 159(12):1140–1149

Hegewald MJ, Crapo RO (2007) Socioeconomic status and lung function. Chest 132:1608–1614

Pahwa P, Senthilselvan A, McDuffie HH et al (2003) Longitudinal decline in lung function measurements among Saskatchewan grain workers. Can Respir J 10:135–141

Huy T, De Schipper K, Chan-Yeung M, Kennedy SM (1991) Grain dust and lung function. Dose–response relationships. Am Rev Respir Dis 144:1314–1321

Wang XR, Zhang HX, Sun BX et al (2005) A 20-year follow-up study on chronic respiratory effects of exposure to cotton dust. Eur Respir J 26(5):881–886

Becklake M, Kauffmann F (1999) Gender differences in airway behaviour over the human life span. Thorax 54(12):1119–1138

Krieger N (2003) Genders, sexes, and health: what are the connections–and why does it matter? Int J Epidemiol 32(4):652–657

Eng A, Mannetje AT, McLean D et al (2011) Gender differences in occupational exposure patterns. Occup Environ Med 68(12):888–894

Statistics Canada (2011) Census of Agriculture. Highlights and analysis. Statistics Canada, Ottawa

Schenker MB, Christiani D, Cormier Y et al (1998) American thoracic society: respiratory health hazards in agriculture. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 158:S1–S76

Habib RR, Hojeij S, Elzein K (2014) Gender in occupational health research of farmworkers: a systematic review. Am J Ind Med 57(12):1344–1367

McDuffie HH, Pahwa P, Dosman JA (1992) Respiratory health status for 3098 Canadian grain workers studied longitudinally. Am J Ind Med 20:753–762

Gan WQ, Man SP, Postma DS et al (2006) Female smokers beyond the perimenopausal period are at increased risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Res 7(1):52

Springer KW, Stellman JM, Jordan-Young RM (2012) Beyond a catalogue of differences: a theoretical frame and good practice guidelines for researching gender in human health. Soc Sci Med 74(11):1817–1824

Pahwa P, Karunanayake CP, Hagel L et al (2012) The Saskatchewan rural health study: an application of a population health framework to understand respiratory health outcomes. BMC Res Notes 5:400

Dillman DA (2000) Mail and internet surveys: the tailored design method, 2nd edn. Wiley, New York

Statement of the American Thoracic Society (1987) Standardization of spirometry: 1987 update. Am Rev Resp Dis 136:1285–1298

Canada Health (2003) Canadian guidelines for body weight classification in adults. Office of Nutrition Policy and Promotion, Ottawa

Statistics Canada (2008) National population health survey household component: documentation for the derived variables and the constant longitudinal variables. Statistics Canada, Ottawa

Chen Y, Rennie D, Cormier YF, Dosman J (2007) Waist circumference is associated with pulmonary function in normal-weight, overweight, and obese subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 85:35–39

Ochs-Balcom HM, Grant BJB, Muti P et al (2006) Pulmonary function and abdominal adiposity in the general population. Chest 129:853–862

Harik-Khan RI, Wise RA, Fleg JL (2001) The effect of gender on the relationship between body fat distribution and lung function. J Clin Epidemiol 54:399–406

Steele R, Finucane F, Griffin S et al (2008) Obesity is associated with altered lung function independently of physical activity and fitness. Obesity 17:578–584

James AL, Palmer LJ, Kicic E et al (2005) Decline in lung function in the Busselton Health Study: the effects of asthma and cigarette smoking. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 171(2):109–114

Chen Y, Horne SL, Dosman JA (1991) Increased susceptibility to lung dysfunction in female smokers. Am Rev Respir Dis 143:1224–1230

Kohansal R, Martinez-Camblor P, Agusti A et al (2009) The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction revisited: an analysis of the Framingham Offspring cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 180:3–10

Xu X, Dockery DW, Ware JH et al (1992) Effects of cigarette smoking on rate of loss of pulmonary function in adults: a longitudinal assessment. Am Rev Respir Dis 146:1345–1348

Jaakkola MS, Jaakkola JJ (2002) Effects of environmental tobacco smoke on the respiratory health of adults. Scand J Work Environ Health 28(2):52–70

Eisner MD (2002) Environmental tobacco smoke exposure and pulmonary function among adults in NHANES III: impact on the general population and adults with current asthma. Environ Health Perspect 110(8):765–770

Mendell MJ, Mirer AG, Cheung K et al (2011) Respiratory and allergic health effects of dampness, mold, and dampness-related agents: a review of the epidemiologic evidence. Environ Health Perspect 119:748–756

Hernberg S, Sripaiboonkij P, Quansah R et al (2014) Indoor molds and lung function in healthy adults. Respir Med 108:677–684

Norback D, Zock JP, Plana E et al (2013) Lung function decline in relation to mould and dampness in the home: the longitudinal European community respiratory health survey ECRHS II. Thorax 66:396–401

Rennie D, Chen Y, Lawson J et al (2005) Different effect of damp housing on respiratory health in women. J Am Med Women Assoc 60:46–51

Melenka LS, Hessel PA, Yoshida K et al (1999) Lung health in Alberta farmers. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 3:913–919

McDuffie HH, Pahwa P, Dosman JA (1992) Respiratory health status for 3098 Canadian grain workers studied longitudinally. Am J Ind Med 20:753–762

Kennedy S, Loehoorn M (2003) Exposure assessment in epidemiology: does gender matter? Am J Ind Med 44:576–583

Messing K, Punnett L, Bond M et al (2003) Be the fairest of them all: challenges and recommendations for the treatment of gender in occupational health research. Am J Ind Med 43:618–629

Quinn MM (2011) Why do women and men have different occupational exposures? Occup Environ Med 68(12):861–862

Dimich-Ward H, Beking K, DyBuncio A et al (2012) Occupational exposure influences on gender differences in respiratory health. Lung 190(2):147–154

Schachter EN, Zuskin E, Moshier EL et al (2009) Gender and respiratory findings in workers occupationally exposed to organic aerosols: a meta-analysis of 12 cross-sectional studies. Environ Health 8(1):1–33

Lai PS, Hang JQ, Zhang FY et al (2013) Gender differences in the effect of occupational endotoxin exposure on impaired lung function and death: the shanghai textile worker study. Occup Environ Med 19:152–157

Lai PS, Hang JQ, Valeri L et al (2015) Endotoxin and gender modify lung function recovery after occupational organic dust exposure: a 30-year study. Occup Environ Med 72:546–552

Heederik D, Smit LA (2014) Gender differences in lung function recovery after cessation of occupational endotoxin exposure: a complex story. Occup Environ Med 72:543–544

Kirychuk SP, Senthilselvan A, Dosman JA et al (2003) Respiratory symptoms and lung function in poultry confinement workers in Western Canada. Can Respir J 10(7):375–380

Radon K, Weber C, Iversen M et al (2001) Exposure assessment and lung function in pig and poultry farmers. Occup Environ Med 58:405–410

Senthilselvan A, Dosman JA, Kirychuk P et al (1997) Accelerated lung function decline in swine confinement workers. Chest 111:1733–1741

Leynaert B, Neukirch C, Jarvis D et al (2001) Does living on a farm during childhood protect against asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopy in adulthood? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164(10):1829–1834

Lampi J, Canoy D, Jarvis D et al (2011) Farming environment and prevalence of atopy at age 31: prospective birth cohort study in Finland. Clin Exp Allergy 41(7):987–993

Lampi J, Koskela H, Hartikainen AL et al (2015) Farm environment during infancy and lung function at the age of 31: a prospective birth cohort study in Finland. BMJ Open 5(7):e007350

Chenard L, Senthiselvan A, Grover V et al (2007) Lung function and farm size predict healthy worker effect in swine farmers. Chest 131:245–254

Gray LA, Leyland AH, Benzeval M, Watt GC (2013) Explaining the social patterning of lung function in adulthood at different ages: the roles of childhood precursors, health behaviours and environmental factors. J Epidemiol Community Health 67(11):905–911

McFadden E, Luben R, Wareham N et al (2009) How far can we explain the social class differential in respiratory function? A cross-sectional population study of 21,991 men and women from EPIC-Norfolk. Eur J Epidemiol 24(4):193–201

Bartley M, Kelly Y, Sacker A (2012) Early life financial adversity and respiratory function in midlife: a prospective birth cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 175(1):33–42

Tennant PW, Gibson GJ, Pearce MS (2008) Lifecourse predictors of adult respiratory function: results from the Newcastle thousand families study. Thorax 63(9):823–830

Wong SL, Shields M, Leatherdale S et al (2012) Assessment of validity of self-reported smoking status. Health Rep 23(1):47

Avila-Tang E, Elf JL, Cummings KM et al (2012) Assessing secondhand smoke exposure with reported measures. Tob Control 22:156–163

Jaakkola MS, Jaakkola JJ (2004) Indoor molds and asthma in adults. Adv Appl Microbiol 55:309–338

Teschke K, Olshan AF, Daniels JL et al (2002) Occupational exposure assessment in case-control studies: opportunities for improvement. Occup Environ Med 59(9):575–594

Camp PG, Dimich-Ward H, Kennedy SM (2004) Women and occupational lung disease: sex differences and gender influences on research and disease outcomes. Clin Chest Med 25(2):269–279

Rothman KJ, Gallacher JE, Hatch EE (2013) Why representativeness should be avoided. Int J Epidemiol 42(4):1012–1014

Acknowledgments

The Saskatchewan Rural Health Study Team consists of James Dosman, MD (Designated Principal Investigator, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK Canada); Dr. Punam Pahwa, PhD (Co-principal Investigator, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon SK Canada); Dr. John Gordon, PhD (Co-principal Investigator, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon SK Canada); Yue Chen, PhD (University of Ottawa, Ottawa Canada); Roland Dyck, MD (University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon SK Canada); Louise Hagel (Project Manager, University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon SK Canada); Bonnie Janzen, PhD (University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon SK Canada); Chandima Karunanayake, PhD (University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon SK Canada); Shelley Kirychuk, PhD (University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon SK Canada); Niels Koehncke, MD (University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon SK Canada); Joshua Lawson, PhD, (University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon SK Canada); William Pickett, PhD (Queen’s University, Kingston ON Canada); Roger Pitbaldo, PhD (Professor Emeritus, Laurentian University, Sudbury ON Canada); Donna Rennie, RN, PhD, (University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon SK Canada); and Ambikaipakan Senthilselvan, PhD (University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada). We are grateful for the contributions of the rural municipality administrators and the community leaders of the towns included in the study that facilitated access to the study populations and to all of participants who donated their time to complete and return the survey.

Funding

Canadian Institutes of Health Research MOP-187209-POP-CCAA-11829.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Additional information

The Saskatchewan Rural Health Study Team are listed in “Acknowledgments.”

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Janzen, B., Karunanayake, C., Rennie, D. et al. Gender Differences in the Association of Individual and Contextual Exposures with Lung Function in a Rural Canadian Population. Lung 195, 43–52 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-016-9950-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-016-9950-8