Abstract

Background and objective

It has been recognized that anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitides may lead to hypertrophic pachymeningitis (HP) or intractable otitis media (OM). To our knowledge, few cases of coexistent ANCA-related HP and OM have been described previously. To increase awareness of this disease, we reviewed the literature describing patients with HP and intractable OM in a population with AAV to guide clinical decision making for otolaryngologists.

Methods

PubMed was searched with the following terms: ANCA-associated vasculitis, otitis media, and hypertrophic pachymeningitis. Only patients with concomitant AAV, OM and HP were considered and included in this review.

Results

A total of 243 articles were reviewed, and of these, 6 met inclusion criteria. Headache, cranial polyneuropathy, and intractable OM with effusion or granulation were common. Serum MPO–ANCA positivity was most common in Asian patients. Almost all patients had dural mater thickening on gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of the brain. Corticosteroids plus an immunosuppressant was more effective and most patients had improved hearing after treatment, but approximately 50% of subjects had disease relapse.

Conclusion

In this review, we summarized the current knowledge on the clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and pathogenesis of this disease. We should carefully detect the potential cases of ANCA-related HP and OM in patients with intractable OM, HP, or AAV, and make the optimal treatment plan to avoid long-term neurological complications and irreversible hearing loss. Furthermore, due to an increased possibility of relapse, close follow-up, including a hearing test, ANCA titers, imaging examination, and detection of toxic and side effects of immunosuppressive therapy, are necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) is a rare necrotizing vasculitis with few or no immune deposits, predominantly affecting small vessels associated with ANCA specific for myeloperoxidase (MPO) or proteinase 3 (PR3). In small vessels, AAV includes granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis) (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) [1,2,3,4,5]. Recently, AAV has been shown to lead to hypertrophic pachymeningitis (HP), which accounts for most AAV cases. HP is a rare chronic disorder characterized by dural thickening. It is idiopathic or secondary to various conditions, such as infections (e.g., neurosyphilis or fungal meningitis), inflammatory disorders (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis or neurosarcoidosis), and neoplasms (e.g., dural carcinomatosis and meningioma). AAV is a major cause of HP, and ANCA-related HP (i.e. ANCA-associated HP) is the most common form among HP patients, representing as many as 34.0% of all HP cases in Japan [6]. In addition, otitis media (OM) may also co-occur with AAV. For example, 30–50% of GPA patients had OM, so and thus the concept of OM with AAV (OMAAV) was proposed to help understand the disease process better [7, 8]. We investigated whether ANCA-related HP and OM can occur simultaneously because Harabuchi’s group reported that 22.2% of ANCA-related HP patients had otologic symptoms, suggesting the presence of OM [8]. In addition, 17% of OMAAV patients were reported to have HP at their initial visit, and 28% have it at the end of the clinical course [6]. Therefore, few patients have ANCA-related HP and OM simultaneously. Some patients may require treatment for hearing loss, headache, with or without cranial nerve paralysis. Such cases are easily misdiagnosed, so better criteria are needed for early diagnosis and to avoid long-term neurological complications and irreversible hearing loss. To guide clinical decision making for otolaryngologists, we performed this review and tried to elucidate the characteristics of patients with HP and intractable OM in a population with AAV.

Materials and methods

PubMed was searched for papers published between 1946 and May, 2018 addressing cases with ANCA-related HP and OM (i.e. AAV with HP and OM, ANCA-related HP and OM, or HP and OM plus AAV). A search strategy was developed with the following terms: HP, OM, AAV (electronic search: “hypertrophic pachymeningitis” AND “otitis media,” “Hypertrophic pachymeningitis” AND “ANCA-associated vasculitis,” “otitis media” AND “ANCA-associated vasculitis,” and “hypertrophic pachymeningitis” AND “otitis media” AND “ANCA-associated vasculitis”). Studies in English, Chinese, and Japanese were included, and full-text articles were reviewed. All patients included had AAV, HP, and intractable OM or they were excluded.

Results

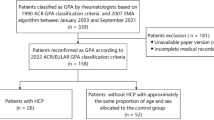

We identified 243 articles but finally reviewed 20 studies describing HP associated with OM (Table 1) [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27], and of these, six met inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Some patient data likely overlapped among studies due to being from similar institutions or case sources. Most patients with coexistent ANCA-related HP and OM were elderly women. Headache, cranial polyneuropathy and otologic symptoms, such as hearing-loss, otorrhea, otalgia, and tinnitus, were common. Serum MPO–ANCA positivity was most common in Asian patients. All patients had dural mater thickening and enhancement on gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain. Treatment consisted of corticosteroid alone; corticosteroid plus immunosuppressant; and corticosteroid alone initially with immunosuppressant added after relapse. Most patients had hearing improvement after treatment, but for almost 50%, hearing loss returned. Relapse was less frequent for patients treated with corticosteroids and an immunosuppressant during their limited follow-up period.

Discussion

Diagnosis

Patients were diagnosed with ANCA-related HP or OMAVV if serum MPO–ANCA and/or PR3-ANCA titers were elevated or if ANCA-related disease (such as GPA, MPA or EGPA) co-occurred with HP or OM. Similarly, patients were diagnosed with ANCA-related HP and OM if AAV patients co-occurred with HP and OM. Consequently, patients with ANCA-related HP and OM could be diagnosed based on established criteria for AAV, HP, and OMAAV. These include histopathology consistent with AAV or positivity for serum MPO–ANCA and/or PR3-ANCA; intractable OM with effusion or granulation that will not respond to antibiotics and tympanic ventilation tubes, and exclusion of other types of OM, such as bacterial OM, choleastoma, tuberculosis, and neoplasms. In addition, diagnosis was made if enhancement of dural mater on contrast-enhanced MRI or chronic inflammatory changes on dural biopsy were noted. Efficacy of corticosteroid and an immunosuppressant such as cyclophosphamide was considered diagnostic for ANCA-related HP and OM.

Clinical presentation

Due to effusion or granulation in the middle ear, progressive conductive hearing loss may occur. Then, sensorineural hearing loss may gradually occur as inner ear disturbances progress. Therefore, three types of hearing impairment may be found: conductive, mixed, and sensorineural hearing loss. Hearing loss was reversible for some cases after therapy, but complete deafness is often difficult to reverse. Profound hearing impairment was evident for patients with OMAAV and 64% of ANCA-positive patients had severe hearing loss [27]. Although more than half of patients had otorrhea, no bacterial pathogens were noted with otorrhea cultures or ear exudate analysis. Cranial nerve involvement may occur for patients with ANCA-related HP and/or OMAAV. For example, 30–50% of those patients had peripheral facial palsy during the clinical course [8]. Furthermore, more diffuse symptoms such as headache and seizures may occur as disease progresses, and severe headache is the most common symptom of HP. This is regarded as an important factor associated with HP occurrence in AAV or OMAAV patients.

Serum ANCA status

Although histopathological identification of necrotizing vasculitis is the key to diagnosing AAV, when pathology cannot be certain or specimens cannot be easily obtained, misdiagnosis may occur [4, 5]. For example, a middle ear specimen often showed a lower positive rate compared to the other specimen taken from nose or lung which may lead to misdiagnosis [28]. Serum ANCA reactivity and clinical symptoms maybe the most important findings for diagnosing AAV. Elevation of ANCA titers is thought to be a highly sensitive and specific serological index for AAV such as GPA, MPA and EGPA [4, 29]. But not all the patients with AAV have positive results on serologic testing for ANCA, for example, for patients with ANCA-negative AAV, they may have ANCA that cannot be detected with current methods or may have ANCA of as yet undiscovered specificity [5]. Moreover, ANCA status may convert to MPO-ANCA and/or PR3-ANCA positivity as disease progresses. ANCA status provides us an important index for documenting therapeutic effects. Patients initially ANCA-positive may revert to ANCA-negative status after therapy, suggesting disease improvement. In contrast, the reappearance of ANCA titers can indicate a relapse.

In previous studies, ANCA status was reported to be influenced by regional factors. For example, MPO–ANCA positivity is more common in China, Japan and Korea, whereas PR3-ANCA is more frequent in Europe and the US [27, 30,31,32,33,34]. MPO–ANCA positivity was more frequent for patients with ANCA-related HP and OM, likely because most relevant reports were from Japanese scholars in this review. ANCA status may be influenced by environmental factors and genetics. A recently published genome-wide association study confirmed that PR3-ANCA was associated with the human major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II isotype HLA-DP, the gene encoding α-1-AT (SERPINA1) and the gene encoding PR3 (PRTN3), whereas MPO-ANCA was associated with MHC class II isotype HLA-DQ [35].

Clinical features vary by ANCA status. Patients with PR3-ANCA positive OM have granulomatous formation or effusion in the middle ear, whereas MPO–ANCA positive OM predominantly presents as OM with effusion [7, 8, 27]. Most patients with MPO–ANCA positive HP have the CNS-limited form and a less severe phenotype compared with patients with PR3-ANCA positive HP [27, 36, 37]. In addition, Studies suggest that PR3-ANCA-positive subjects had greater involvement of brain parenchyma, renal parenchyma and lung compared with MPO–ANCA positive subjects [38]. However, whether patients with PR3-ANCA positivity have more severe neurological damage and more severe disease compared with patients who are MPO–ANCA positive is still unclear, and the association between ANCA status and disease severity is not clear either.

Radiology

Imaging may be used to identify OM and fibrotic meningeal lesions of HP, analyze adjacent structures, and evaluate curative effects of ANCA-related HP and OM. Computed tomography (CT) of the temporal bones is useful for diagnosing OM, and the middle ear and mastoid cavities filled with soft tissue material are common (Fig. 2). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offers some advantages over CT for the assessment of meningeal lesions. Contrast-enhanced MRI of the brain or spine can be used to diagnose HP, and gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted MRI reveals thickening of the dural mater, especially when it is difficult to obtain specimen or make a positive diagnosis of HP with histopathology. Moreover, axial T2-weighted MRI may be used to observe inflammation of the middle ear and mastoid cavities.

There have been reported significant overlaps in the distribution pattern of dural enhancement among patients with MPO–ANCA positive HP, PR3-ANCA positive HP, immune-mediated, and idiopathic HP, and there is no consensus on the correlation between dural enhancement pattern and HP etiology [27, 39]. But fortunately, recent imaging studies indicated that most patients with MPO–ANCA positive HP have the CNS-limited form and less frequent leptomeningeal or parenchymal involvement than those with PR3-ANCA-positivity [36, 37]. However, the association between ANCA status and dural enhancement pattern of HP and its pathological mechanism remain to be further studied.

Treatment

Treatment of AAV includes remission induction and maintenance. The European League against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommended that AAV should be treated according to severity and organ involvement with prednisolone and cyclophosphamide used for remission and induction for patients with organ-threatening AAV. Prednisolone and methotrexate can be used for remission and induction of patients with AAV with non-organ threatening or non-life threatening disease [40]. Corticosteroid and cyclophosphamide are more effective than corticosteroid alone, offering long-term remission, better hearing outcomes, and survival for patients with ANCA-positive HP or OMAAV [7, 8, 27, 30, 41]. Therefore, initial treatment with corticosteroid and an immunosuppressant such as cyclophosphamide should be recommended for ANCA-positive HP and OM, moreover, it should be also used in the event of a recurrence [5, 42, 43]. Thus, it can be seen that the treatment for this subgroup of patients with AAV is different from other AAV patients with non-organ threatening disease. Furthermore, the treatment of this disease is different from that of intractable OM or HP caused by other etiologies. For example, for patients with idiopathic HP, concomitant OM and HP, or IgG4-related HP, most of the published reports reveal a preference for corticosteroid treatment, followed by the addition of an immunosuppressant at relapse [6, 14, 17, 44].

Therapy has improved for AAV treatment, but most treatment recommendations are empirical and require more study. For example, immunosuppressant selection and dose adjustment is based on patient age, ANCA status, and disease severity but these need more scrutiny. In addition, immunosuppressive regimens may be associated with gonadal toxicity, diabetes, thromboembolism, and cardiovascular disease. A recent study suggested that death due to adverse events in the first year of treatment was three times more likely than from vasculitis itself [45, 46]. Therefore, new highly selective immunosuppressant drugs that have little toxicity are needed.

Pathogenesis

Although the etiology and mechanism of ANCA-related HP plus OM is unclear, increasing awareness of AAV contributes to understanding ANCA-related HP and OMAAV due to a common etiologic basis. AAV is considered to be an autoimmune disease associated with ANCA. In vitro and animal models suggest that ANCA may contribute to the formation of small vessel vasculitis [47]. MPO and PR3 specific ANCA can activate neutrophils and monocytes via interactions with target antigens translocated from the lysosomal compartment to the cell surface due to triggers such as infectious agents, cytokines, and chemokines. Activated neutrophils not only release free oxygen radicals and lytic enzymes but also trigger endothelial activation [48, 49]. Although the role of ANCA is generally accepted, studies confirm that normal individuals without vasculitis were positive for ANCA [50]. In addition, TH1-predominant granulomatous lesions were found in patients with ANCA-positive HP, suggesting that ectopic lymphoid neogenesis may play a role [27]. In summary, AAV may involve molecular signaling pathways with positive or negative feedback loops.

Whether a potential relationship exists between HP and OM occurring in AAV patients is unclear. Some studies suggest a relationship that is associated with middle ear and dural mater anatomy (Fig. 3) [7, 17, 19, 27]. For example, small vasculitis leading to granulation or effusion in the middle ear may spread to the dural mater and lead to secondary HP via several ways: damaged tympanicum tegmentum; temporal bone sutura or fissure; the inner ear including the labyrinth and vestibule; local circulation via venous return communicating with the middle ear and the dural mater in the middle and/or the posterior cranial fossa. In addition, small vasculitis or granulomatous lesions in the dural mater may also spread to the middle ear via the above ways and cause OM. In addition, the occurrence of ANCA-related HP and OM may be thought of as distinct but synchronous events.

Conclusions

Here, we summarize clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of ANCA-related HP and OM and its etiology (Fig. 4). Early hearing loss may be reversible due to cochlear homeostatic function, so rapid diagnosis and treatment are critical for recovery of auditory function [7, 8, 27, 51]. In addition, we should carefully screen out the potential cases with ANCA-related HP and OM in a population with intractable OM, HP, or AAV, and make appropriate treatment. Initial treatment with corticosteroids and an immunosuppressant should be recommended. However, due to an increased possibility of relapse, close follow-up with a hearing test, MRI, and ANCA titers, is needed. Furthermore, prevention and management of the adverse effects associated with immunosuppressive therapy is very important for patients with ANCA-related HP and OM.

References

Leavitt RY1, Fauci AS, Bloch DA, Michel BA, Hunder GG, Arend WP, Calabrese LH, Fries JF, Lie JT, Lightfoot RW Jr et al (1990) The American college of rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Wegener’s granulomatosis. Arthritis Rheum 33(8):1101–1107

Lightfoot RW Jr, Michel BA, Bloch DA, Hunder GG, Zvaifler NJ, McShane DJ, Arend WP, Calabrese LH, Leavitt RY, Lie JT et al (1990) The American college of rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of polyarteritis nodosa. Arthritis Rheum 33(8):1088–1093

Masi AT, Hunder GG, Lie JT, Michel BA, Bloch DA, Arend WP, Calabrese LH, Edworthy SM, Fauci AS, Leavitt RY et al (1990) The American college of rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Churg–Strauss syndrome (allergic granulomatosis and angiitis). Arthritis Rheum 33(8):1094–1100

Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Andrassy K, Bacon PA, Churg J, Gross WL, Hagen EC, Hoffman GS, Hunder GG, Kallenberg CG et al (1994) Nomenclature of systemic vasculitides: proposal of an international consensus conference. Arthritis Rheum 37(2):187–192

Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, Basu N, Cid MC, Ferrario F, Flores-Suarez LF, Gross WL, Guillevin L, Hagen EC, Hoffman GS, Jayne DR, Kallenberg CG, Lamprecht P, Langford CA, Luqmani RA, Mahr AD, Matteson EL, Merkel PA, Ozen S, Pusey CD, Rasmussen N, Rees AJ, Scott DG, Specks U, Stone JH, Takahashi K, Watts RA (2013) 2012 Revised international chapel hill consensus conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum 65(1):1–11

Yonekawa T, Murai H, Utsuki S, Matsushita T, Masaki K, Isobe N, Yamasaki R, Yoshida M, Kusunoki S, Sakata K, Fujii K, Kira J (2013) A nationwide survey of hypertrophic pachymeningitis in Japan. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 85(7):732–739

Yoshida N, Iino Y (2014) Pathogenesis and diagnosis of otitis media with ANCA-associated vasculitis. Allergol Int 63(4):523–532

Harabuchi Y, Kishibe K, Tateyama K, Morita Y, Yoshida N, Kunimoto Y, Matsui T, Sakaguchi H, Okada M, Watanabe T, Inagaki A, Kobayashi S, Iino Y, Murakami S, Takahashi H, Tono T (2017) Clinical features and treatment outcomes of otitis media with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (OMAAV): a retrospective analysis of 235 patients from a nationwide survey in Japan. Mod Rheumatol 27(1):87–94

Ishii A, Ohkoshi N, Nagata H, Mizusawa H, Kanazawa I (1991) A case of Garcin’s syndrome caused by pachymeningitis secondary to otitis media, responsive to antibiotic therapy. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 31(8):837–841

Murai H, Kira J, Kobayashi T, Goto I, Inoue H, Hasuo K (1992) Hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis due to Aspergillus flavus. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 94:247–250

Oku T, Yamashita M, Inoue T, Sayama T, Kodama T, Nagatomi H, Wakisaka S (1995) A case of posterior fossa hypertrophic pachymeningitis with hydrocephalus. No To Shinkei 47(6):569–573

Adachi M, Hayashi A, Ohkoshi N, Nagata H, Mizusawa H, Shoji S, Tabei F, Matsumura A (1995) Hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis with spinal epidural granulomatous lesion. Intern Med 34(8):806–810

Yi Z, Zhang R, Xiao W, Lin X, Lin Y (2000) Otogenic hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis associated with edema of the temporal lobe and organic mental disorder-case report. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Ke Za Zhi 35(4):271–274

Kanzaki S, Inoue Y, Watabe T, Ogawa K (2004) Hypertrophic chronic pachymeningitis associated with chronic otitis media and mastoiditis. Auris Nasus Larynx 31(2):155–159

Sato Y, Aoyama M, Soeda T, Hoshi A, Honma M, Yamamoto T (2004) A case of hypertrophic pachymeningitis, resolved by antimicrobial therapy. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 44(8):527–530

Tada M, Onodera O, Hara K, Tanaka K, Takahashi H, Tsuji S, Nishizawa M (2006) Oral cyclophosphamide therapy for multifocal fibrosclerosis with hypertrophic intracranial pachymeningitis. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 46(2):128–133

Iwasaki S, Ito K, Sugasawa M (2006) Hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis associated with middle ear inflammation. Otol Neurotol 27(7):928–933

Bravo D, Machová H, Hahn A, Marková H, Otruba L, Mandys V, Houstava L, Kalvach P (2007) Mastoiditis complicated with Gradenigo syndrome and a hypertrophic pachymeningitis with consequent communicating hydrocephalus. Acta Otolaryngol 127(1):93–97

Lu HT, Li MH, Hu DJ, Li WB, Pan YP, Zee CS (2009) Hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis accompanied by inflammation of the nasopharygeal soft tissue. Headache 49(8):1229–1231

Kobayakawa Y, Tanaka K, Matsumoto S, Tanaka K, Kawajiri M, Yamada T (2010) Recurrent idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis after surgery of chronic otitis media with cholesteatoma: a case report. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 50(7):489–492

Hasegawa H, Kohsaka H, Takada K, Miyasaka N (2012) Renal involvement in antimyeloperoxidase antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive granulomatosis with polyangiitis with chronic hypertrophic pachymeningitis. J Rheumatol 39(10):2053–2055

Mori A, Hira K, Hatano T, Okuma Y, Kubo S, Hirano K, Ohno K, Noda K, Suzuki H, Ohsawa I, Hattori N (2013) Bilateral facial nerve palsy due to otitis media associated with myeloperoxidase-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody. Am J Med Sci 346(3):240–243

Keshavaraj A, Gamage R, Jayaweera G, Gooneratne IK (2012) Idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis presenting with a superficial soft tissue mass. J Neurosci Rural Pract 3(2):193–195

Saito T, Fujimori J, Yoshida S, Kaneko K, Kodera T (2014) Case of cerebral venous thrombosis caused by MPO–ANCA associated hypertrophic pachymeningitis. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 54(10):827–830

Okada M, Hato N, Okada Y, Sato E, Yamada H, Hakuba N, Gyo K (2015) A case of hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis associated with invasive Aspergillus mastoiditis. Auris Nasus Larynx 42(6):488–491

Fujimoto M, Kira J, Murai H, Yoshimura T, Takizawa K, Goto I (1993) Hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis associated with mixed connective tissue disease; a comparison with idiopathic and infectious pachymeningitis. Intern Med 32(6):510–512

Yokoseki A, Saji E, Arakawa M, Kosaka T, Hokari M, Toyoshima Y, Okamoto K, Takeda S, Sanpei K, Kikuchi H, Hirohata S, Akazawa K, Kakita A, Takahashi H, Nishizawa M, Kawachi I (2014) Hypertrophic pachymeningitis: significance of myeloperoxidase anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody. Brain 137(Pt 2):520–536

Takagi D, Nakamaru Y, Maguchi S, Furuta Y, Fukuda S (2002) Otologic manifestations of Wegener’s granulomatosis. Laryngoscope 112(9):1684–1690

Sablé-Fourtassou R, Cohen P, Mahr A, Pagnoux C, Mouthon L, Jayne D, Blockmans D, Cordier JF, Delaval P, Puechal X, Lauque D, Viallard JF, Zoulim A, Guillevin L, French Vasculitis Study Group (2005) Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and the Churg–Strauss syndrome. Ann Intern Med 143(9):632–638

Ono N, Yoshihiro K, Oryoji D, Matsuda M, Ueki Y, Uezono S, Kai Y, Himeji D, Niiro H, Ueda A (2013) Four cases of MPO–ANCA-positive vasculitis with otitis media, and review of the literature. Mod Rheumatol 23(3):554–563

Lim EJ, Kim SH, Lee SH, Lee KY, Choi JH, Nam EJ, Lee SH (2011) Reversible sensorineural hearing loss due to pachymeningitis associated with elevated serum MPO–ANCA. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol 4(3):155–158

Nikolaou AC, Vlachtsis KC, Daniilidis MA, Petridis DG, Daniilidis IC (2001) Wegener’s granulomatosis presenting with bilateral facial nerve palsy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 258(4):198–202

Iqbal AM, Blackburn D, Rafiq M, Sharrack B (2013) Wegener’s granulomatosis presenting with multiple cranial nerve palsies and pachymeningitis. Pract Neurol 13(3):193–195

Taylor SC, Clayburgh DR, Rosenbaum JT, Schindler JS (2012) Progression and management of Wegener’s granulomatosis in the head and neck. Laryngoscope 122(8):1695–1700

Lyons PA, Rayner TF, Trivedi S, Holle JU, Watts RA, Jayne DR, Baslund B, Brenchley P, Bruchfeld A, Chaudhry AN, Cohen Tervaert JW, Deloukas P, Feighery C, Gross WL, Guillevin L, Gunnarsson I, Harper L, Hrušková Z, Little MA, Martorana D, Neumann T, Ohlsson S, Padmanabhan S, Pusey CD, Salama AD, Sanders JS, Savage CO, Segelmark M, Stegeman CA, Tesař V, Vaglio A, Wieczorek S, Wilde B, Zwerina J, Rees AJ, Clayton DG, Smith KG (2012) Genetically distinct subsets within ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med 367(3):214–223

Cartin-Ceba R, Peikert T, Specks U (2012) Pathogenesis of ANCA-associated vasculitis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 14(6):481–493

Holle JU, Gross WL, Holl-Ulrich K, Ambrosch P, Noelle B, Both M, Csernok E, Moosig F, Schinke S, Reinhold-Keller E (2010) Prospective long-term follow-up of patients with localised Wegener’s granulomatosis: does it occur as persistent disease stage? Ann Rheum Dis 69(11):1934–1939

Lionaki S, Blyth ER, Hogan SL, Hu Y, Senior BA, Jennette CE, Nachman PH, Jennette JC, Falk RJ (2012) Classification of antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody vasculitides: the role of antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody specificity for myeloperoxidase or proteinase 3 in disease recognition and prognosis. Arthritis Rheum 64(10):3452–3462

Hahn LD, Fulbright R, Baehring JM (2016) Hypertrophic pachymeningitis. J Neurol Sci 367:278–283

Mukhtyar C, Guillevin L, Cid MC, Dasgupta B, de Groot K, Gross W, Hauser T, Hellmich B, Jayne D, Kallenberg CG, Merkel PA, Raspe H, Salvarani C, Scott DG, Stegeman C, Watts R, Westman K, Witter J, Yazici H, Luqmani R, European Vasculitis Study Group (2009) EULAR recommendations for the management of primary small and medium vessel vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis 68(3):310–317

Furukawa Y, Matsumoto Y, Yamada M (2004) Hypertrophic pachymeningitis as an initial and cardinal manifestation of microscopic polyangiitis. Neurology 63(9):1722–1724

Stone JH, Merkel PA, Spiera R, Seo P, Langford CA, Hoffman GS, Kallenberg CG, St Clair EW, Turkiewicz A, Tchao NK, Webber L, Ding L, Sejismundo LP, Mieras K, Weitzenkamp D, Ikle D, Seyfert-Margolis V, Mueller M, Brunetta P, Allen NB, Fervenza FC, Geetha D, Keogh KA, Kissin EY, Monach PA, Peikert T, Stegeman C, Ytterberg SR, Specks U, RAVE-ITN Research Group (2010) Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med 363(3):221–232

Jones RB, Tervaert JW, Hauser T, Luqmani R, Morgan MD, Peh CA, Savage CO, Segelmark M, Tesar V, van Paassen P, Walsh D, Walsh M, Westman K, Jayne DR, European Vasculitis Study Group (2010) Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide in ANCA-associated renal vasculitis. N Engl J Med 363(3):211–220

Lu LX, Della-Torre E, Stone JH, Clark SW (2014) IgG4-related hypertrophic pachymeningitis: clinical features, diagnostic criteria, and treatment. JAMA Neurol 71(6):785–793

Little MA, Nightingale P, Verburgh CA, Hauser T, De Groot K, Savage C, Jayne D, Harper L, European Vasculitis Study (EUVAS) Group (2010) Early mortality in systemic vasculitis: relative contribution of adverse events and active vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis 69(6):1036–1043

Miloslavsky EM, Specks U, Merkel PA, Seo P, Spiera R, Langford CA, Hoffman GS, Kallenberg CG, St Clair EW, Tchao NK, Viviano L, Ding L, Sejismundo LP, Mieras K, Iklé D, Jepson B, Mueller M, Brunetta P, Allen NB, Fervenza FC, Geetha D, Keogh K, Kissin EY, Monach PA, Peikert T, Stegeman C, Ytterberg SR, Stone JH, Rituximab in ANCA-Associated Vasculitis-Immune Tolerance Network Research Group (2013) Clinical outcomes of remission induction therapy for severe antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum 65(9):2441–2449

Heeringa P, Little MA (2011) In vivo approaches to investigate ANCA-associated vasculitis: lessons and limitations. Arthritis Res Ther 13(1):204

Jennette JC, Xiao H, Falk RJ (2006) Pathogenesis of vascular inflammation by anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. J Am Soc Nephrol 17(5):1235–1242

Ciavatta DJ, Yang J, Preston GA, Badhwar AK, Xiao H, Hewins P, Nester CM, Pendergraft WF 3rd, Magnuson TR, Jennette JC, Falk RJ (2010) Epigenetic basis for aberrant upregulation of autoantigen genes in humans with ANCA vasculitis. J Clin Invest 120(9):3209–3219

Girard T, Mahr A, Noël LH, Cordier JF, Lesavre P, André MH, Guillevin L (2001) Are antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies a marker predictive of relapse in Wegener’s granulomatosis? A prospective study. Rheumatology 40(2):147–151

Shi X (2011) Physiopathology of the cochlear microcirculation. Hear Res 282(1–2):10–24

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ph.D. Xunqiang Yin, School of Public Health, Central South University, for his great help in the data analysis. In addition, we are very grateful to Dr. Chunyu Wang, Department of Neurology, the Second Xiangya Hospital. She provided professional expertise in this article. We would like to thank LetPub (http://www.letpub.com) for providing linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81570928 and 30700940).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, A., Yang, X., Wu, W. et al. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis and otitis media: a review of literature. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 275, 2915–2923 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-018-5172-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-018-5172-4