Abstract

Early complications of myocutaneous flap transfers following surgical eradication of head and neck tumors have been extensively described. However, knowledge concerning long-term complications of these techniques remains limited. We report the cases of two patients with a prior history of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (HNSCC), who developed a second primary SCC on the cutaneous surface of their flaps, years after reconstruction. Interestingly, it seems that the well-known risk of a second primary SCC in patients with previous head and neck carcinoma also applies to foreign tissues implanted within the area at risk. Given the important expansion of these interventions, this type of complication may become more frequent in the future. Therefore, long-term follow-up of patients previously treated for HNSCC not only requires careful evaluation of the normal mucosa of the upper aero-digestive tract, but also of the cutaneous surface of the flap used for reconstruction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Since Bakamjian described pharyngo-esophageal reconstruction using a deltopectoral flap in 1965 [1], various types of myocutaneous flaps have been developed for the surgical reconstruction of head and neck defects [2–4]. These advances have allowed more extensive eradication of head and neck tumors. While the true benefit of these interventions in terms of survival is still a matter of debate, they have allowed better loco-regional control of the disease and improved cosmetic outcomes as well as functional rehabilitation. The common complications of myocutaneous flaps have been described extensively in the literature [5, 6]. However, only a few cases of second primary tumors developing within skin flaps have been reported thus far. We present two cases involving the late development of a second primary squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), arising in both the skin of a deltopectoral flap and that of a free forearm flap used for the reconstruction of head and neck defects following surgical eradication of the primary tumor.

Report of two cases

Case no. 1

In September 2001, a 58-year-old man was referred to the Otolaryngology, Head, and Neck Surgery Department of the University Hospital of Lausanne, Switzerland, following the diagnosis of an exophytic lesion of the left tonsil by his dentist. The patient had a past history of heavy cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption.

A biopsy specimen of the lesion was diagnosed as SCC. The patient underwent a trans-mandibular resection of the tumor together with a complete left functional neck dissection and a tracheotomy. A left forearm free flap was used to reconstruct the defect of the retromolar space. Anatomopathological studies showed a moderate to poorly differentiated SCC of the upper tonsillar region extending to the soft palate with two lymph node metastases (pT2, pN2b, M0 stage). Medial surgical margins returned positive for in situ SCC. Three days following surgery, partial necrosis of the skin flap required replacement by a new radial forearm free flap. During the intervention, further excision of the medial surgical margin allowed eradication of the remaining in situ SCC. No further complications were encountered. The patient was discharged home 5 weeks after the primary surgery without postoperative radiotherapy. He had stopped smoking and drinking alcohol since the first operation. He was followed closely for 3.5 years with no evidence of recurrent disease until 2005.

In August 2005, an exophytic lesion was identified on the lower portion of the free forearm flap during routine follow-up examination. Histopathological study of the lesion revealed an SCC. The patient underwent endoscopic CO2 laser resection of the tumor. The surgical specimen displayed a 2.3 cm in diameter tumor that had arisen from the skin of the flap used for the reconstruction of the retromolar space. Histologically, the tumor was a well differentiated invasive SCC arising from an in situ SCC of the adjacent skin (Fig. 1). The skin flap could easily be identified by the presence of multiple foci of hyperkeratosis, the existence of actinic elastosis in the superficial dermis as well as the presence of persistent hair follicles and sweat glands in the dermis. Deep surgical margins were composed of hypodermic adipose tissue. The resection margins were free of tumor. The patient was discharged soon after the operation and has been followed up for 2 years thus far, without evidence of recurrent disease.

Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining of SCC arising in the free forearm skin flap of the case no. 1 (a). The tumor cells show a strong immunoreactivity with anti-sera to cytokeratins 5/6 (b). They are negative for cytokeratin 7 immunostaining (c), which is in contrast positive in residual sweat glands (arrow). Over expression of p53 (d) is confined to SCC cells with no immunoreactivity in adjacent non-neoplastic skin. Original magnification ×20 (a, b, c) and ×40 (d)

Case no. 2

In September, 1985, a 44-year-old man visited the Otolaryngology, Head, and Neck Surgery Department of the University Hospital of Lausanne, Switzerland, following the detection of a carcinomatous lesion located in the right, upper tonsillar region with extension to the soft palate. The patient had a past history of cigarette smoking.

A biopsy specimen of the lesion confirmed the diagnosis of SCC. The patient underwent a trans-mandibular resection of the tumor together with a complete right functional neck dissection and a tracheotomy. Reconstruction of the surgical defect using a deltopectoral flap was performed. Histopathological findings showed a moderately differentiated SCC of the right upper tonsil extending to the soft palate with four homolateral lymph node metastases with extracapsular spread (pT4, pN3, M0 stage). Surgical margins were free of tumor. The patient did not face any postoperative complications. He was discharged soon after the operation. Adjuvant radiotherapy was given. The patient was followed closely for 10 years with no evidence of recurrent disease until 1995. He had stopped smoking since the first operation.

In November 1995, the patient underwent a total circular pharyngo-laryngectomy followed by reconstruction with a free jejunal flap for a well-differentiated transglottic SCC (pT4, pN0, M0 stage). The procedure went without postoperative complications. Routine follow-ups were performed with no evidence of recurrent disease until 2005.

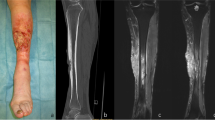

In May 2005, a white-colored thickening surrounded by a hyper-pigmented area in the skin of the deltopectoral flap was identified during routine follow-up examination. Clinically, the lesion appeared as a leucoplakia. Biopsy of the lesion revealed an SCC. The patient underwent endoscopic CO2 laser resection of the tumor. Histopathological analysis demonstrated a tumor of 2.4 × 0.5 × 0.2 cm that had arisen from the skin of the flap used for the reconstruction of the pharynx. The surgical specimen corresponded to a muco-cutaneous fragment with atrophic hair follicles and sweat glands located in the dermis (Fig. 2). Loss of epithelial keratinization was also identified. The tumor was a well-differentiated invasive SCC arising from foci of high-grade dysplasia and in situ SCC of the adjacent skin. The resection margins were free of tumor. The patient was discharged soon after the operation and has been followed for 2 years, with no evidence of recurrent disease.

HE staining of SCC arising in the deltopectoral skin flap of the case no. 2 (a) with presence of residual hypodermic adipose tissue (arrow). The immunohistochemical profile of cytokeratins 5/6 (b), cytokeratine 7 (c), and expression of p53 (d), is identical to the one observed in the case no. 1 (Fig. 1). Original magnification ×20 (a, b, c) and ×40 (d)

Discussion

We report two cases of SCC arising in the skin of both, a forearm free flap and a deltopectoral flap, used for the reconstruction of pharyngeal defects in two head and neck cancer patients, 3 and 20 years following surgery, respectively. To our knowledge, only four similar cases have been described thus far in the literature. Iseli et al. [7] reported an SCC arising in a deltopectoral flap used for the reconstruction of the hypopharynx, 27 years after total laryngectomy. Sakamoto et al. [8] reported a second primary SCC arising in a radial forearm flap used for the reconstruction of the hypopharynx, 10 years after surgery. Deans et al. [9] reported the late development of an SCC in a deltopectoral flap used to reconstruct the pharyngeal defect, 24 years following total laryngectomy. Finally, Scott and Klaassen [10] reported an SCC arising in a pedicled flap used to reconstruct the floor of the mouth, 40 years after jaw reconstruction.

These reports, together with ours, suggest different potential mechanisms involved in the development of such complications. These include the colonization of the flap by residual tumor cells from the primary lesion, the development of a second primary tumor from the oral mucosa adjacent to the flap that has colonized the skin of the reconstructed zone, a second primary tumor that already existed in the skin flap at the time of reconstruction and finally, a second primary tumor induced by the exposure of the skin flap to new environmental conditions.

Similar to other reports, at least 3 years had elapsed between the first operation of both of our patients and the development of the second malignant lesion on the skin flap. Therefore, the possibility that the second primary carcinomas may have resulted from the colonization by residual tumor cells after surgery is almost nil. In both cases, we could identify areas of epithelial dysplasia and in situ carcinoma at the periphery of the invasive component of the tumor (Figs. 1, 2). The presence of persistent dermal appendages in the tumor vicinity was also identified. Furthermore, the invasive portion of the tumor was seen at some distance from the junction with the adjacent oral mucosa. These findings indicate that the second primary tumor most likely arose from a multi-step carcinogenic process that affected the epithelium of the implanted skin flap instead of colonization by residual cells from the primary tumor. For similar reasons, a second tumor arising in the oral mucosa adjacent to the flap that would have spread onto the cutaneous epithelium is also unlikely.

Montgomery et al. [11] reported a second primary SCC occurring in the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap used for the reconstruction of an anterior defect of the floor of the mouth. Based on the fact that a previous history of multiple cutaneous SCCs of the chest wall was known in this patient, the authors concluded that an occult microscopic tumor already existed in the flap prior to its transfer. The presence of hyperkeratosis and the existence of actinic elastosis in the superficial dermis of the skin flap in our first patient (Case no. 1) are evidence of prolonged UV exposure. It is, therefore, possible that in this case, UV exposure could have played a role in the development of the second primary cancer. This does not imply, however, that a microscopic lesion already existed at the time of transfer of the flap. The relatively short period of time that elapsed between the surgery and the occurrence of the second primary tumor in both cases also supports this hypothesis. However other reports together with our second case suggest that, in the absence of a history of chronic UV exposure, between 10 and 40 years may elapse before a second primary tumor will develop on a skin flap [7–10]. For this reason, the hypothesis of a second primary tumor induced by UV exposure, at least in our second case, is unlikely.

We believe that the most likely mechanism involved in the late development of a second primary SCC arising in a skin flap used for the reconstruction of head and neck defects is the development of a tumorigenic process induced by modifications of environmental conditions of the cutaneous epithelium. However, at this stage, identification of such carcinogenic processes remains only speculative. Common carcinogens of head and neck SCCs, such as alcohol and cigarette consumption, could be implicated [12]. Sakamoto et al. [8] concluded that although smoking had been given up after the first operation, chronic alcohol consumption was not, and was likely involved in the development of a second primary SCC in the flap of their patient, 10 years after surgery. Consistent with the report from Iseli et al. [7], the potential involvement of cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption is, however, not relevant in our cases. Indeed, both of our patients had quit smoking and stopped alcohol consumption after the first surgical intervention.

Of particular interest is the apparent tendency of the grafted skin to undergo metaplastic transformations that mimic the histological features of the oral mucosa. These changes include the loss of keratinization and the partial disappearance of dermal structures such as hair follicles and sweat glands. These changes have been described previously by Badran et al. [13]. Whether oral metaplasia of skin grafts represents the first step of a carcinogenic process in response to yet unknown oral stimuli, is an attractive hypothesis. Indeed, metaplastic transformations in other clinical situations, such as intestinal metaplasia in Barrett’s esophagus, are well-described predisposing factors to malignant transformation. The mechanism behind the metaplastic transformation of the skin epithelium after transfer to the oral cavity as well as its potential predisposing influence on neoplastic transformation, are yet to be explored. It could come from external stimuli, such as saliva or dietary substances that may influence the phenotype of cutaneous cells leading to morphological and physiological characteristics, closely mimicking those of the oral mucosa. Prolonged exposure to such non-physiological stimuli for skin cells may finally trigger neoplastic changes that do not occur in normal epithelial cells of the upper aerodigestive tract. Another putative mechanism could involve the migration, colonization, and subsequent replacement of cutaneous cells by epithelial cells from the nearby oral mucosa. This hypothesis would fit with the well-known risk of metachronous SCC development in patients with previous head and neck carcinoma. Indeed, colonizing epithelial cells would come from mucosal areas that have been chronically exposed to common carcinogens of the head and neck [12]. Therefore, these cells already possess all of the genetic alterations that are predisposing to SCC transformation. If this mechanism were true, then long-term implanted skin flaps of head and neck regions would progressively acquire similar risks of developing metachronous malignant lesions as the rest of the epithelial lining of the upper aerodigestive tract. The fact that morphological, as well as immunohistochemical features, of the second primary tumors are strictly identical to those of SCCs classically encountered in the head and neck region further support this hypothesis (Figs. 1, 2).

Conclusions

It appears that skin flaps used to reconstruct the upper aerodigestive tract progressively acquire the potential to undergo metaplastic changes as well as subsequent malignant transformation. Thus far, the cellular mechanisms involved remain purely speculative. Second primary SCCs arising in the skin of myocutaneous flaps may become more common in the future, because the clinical application of these procedures in reconstructive surgery for patients with head and neck cancers has expanded tremendously. Therefore long-term follow-up of patients with former head and neck cancer not only requires careful evaluation of the normal mucosa of the upper aerodigestive tract but also of the cutaneous surface of the flap used for reconstruction.

References

Bakamjian VY (1965) A two-stage method for pharyngoesophageal reconstruction with a primary pectoral skin flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 36:173–184

Arian S (1979) The pectoralis major myocutaneous flap. Plastic Reconstr Surg 63:73–81

McConnel FM, Hester TR Jr, Nahai F et al (1981) Free jejunal grafts for reconstruction of pharynx and cervical esophagus. Arch Otolaryngol 107:476–481

Song R, Gao Y, Song Y et al (1982) The forearm flap. Clin Plast Surg 9:21–26

Maisel RH, Liston SL, Adams GL (1983) Complications of pectoralis myocutaneous flaps. Laryngoscope 93:928–930

Ossoff RH, Wurster CF, Berktold RE et al. (1983) Complications after pectoralis major myocutaneous flap reconstruction of head and neck defects. Arch Otolaryngol 109:812–814

Iseli TA, Hall FT, Buchanan MR et al (2002) Squamous cell carcinoma arising in the skin of a deltopectoral flap 27 years after pharyngeal reconstruction. Head Neck 24:87–90

Sakamoto M, Nibu K, Sugasawa M et al (1998) A second primary squamous cell carcinoma arising in a radial forearm flap used for reconstruction of the hypopharynx. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 60:170–173

Deans JA, Hill J, Welch AR et al (1990) Late development of a squamous carcinoma in a reconstructed pharynx. J Laryngol Otol 104:827–828

Scott MJ, Klaassen MF (1992) Squamous cell carcinoma in a tube pedicle forty years after jaw reconstruction. Br J Plast Surg 45:70–71

Montgomery WW, Varvares MA, Samson MJ et al (1993) Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma occurring in a pectoralis major myocutaneous flap. Case report and literature review. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 102:206–208

Cann CI, Fried MP, Rothman KJ (1985) Epidemiology of squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 18:367–388

Badran D, Soutar DS, Robertson AG et al (1998) Behavior of radial forearm skin flaps transplanted into the oral cavity. Clin Anat 11:379–389

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Monnier, Y., Pasche, P., Monnier, P. et al. Second primary squamous cell carcinoma arising in cutaneous flap reconstructions of two head and neck cancer patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 265, 831–835 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-007-0526-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-007-0526-3