Abstract

Purpose

First trimester risk assessment for chromosomal abnormalities plays a major role in the contemporary pregnancy care. It has evolved significantly since its introduction in the 1990s, when it essentially consisted of just the nuchal translucency measurement. Today, it involves the measurement of several biophysical and biochemical markers and it is often combined with a cell-free DNA (cfDNA) analysis as a secondary test.

Methods

A search of the Medline and Embase databases was done looking for articles about first trimester aneuploidy screening. We performed a detailed review of the literature to evaluate the screening tests currently available and their respective test performance.

Results

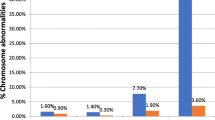

Combined screening for trisomy 21 based on maternal age, fetal NT, and the serum markers free beta-hCG and PAPP-A results in a detection rate of about 90% for a false positive of 3–5%. With the addition of further ultrasound markers, the false positive rate can be roughly halved. Screening based on cfDNA identifies about 99% of the affected fetuses for a false positive rate of 0.1%. However, there is a test failure rate of about 2%. The ideal combination between combined and cfDNA screening is still under discussion. Currently, a contingent screening policy seems most favorable where combined screening is offered for everyone and cfDNA analysis only for those with a borderline risk result after combined screening.

Conclusion

Significant advances in screening for trisomy 21 have been made over the past 2 decades. Contemporary screening policies can detect for more than 95% of affected fetuses for false positive rate of less than 3%.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Nicolaides KH (2011) A model for a new pyramid of prenatal care based on the 11–13 weeks’ assessment. Prenat Diagn 31:3–6. doi:10.1002/pd.2685

Snijders R, Noble P, Sebire N et al (1998) UK multicentre project on assessment of risk of trisomy 21 by maternal age and fetal nuchal-translucency thickness at 10–14 weeks of gestation. Lancet 352:343–346. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11280-6

Nicolaides KH, Azar G, Byrne D et al (1992) Fetal nuchal translucency: ultrasound screening for chromosomal defects in first trimester of pregnancy. BMJ 304:867–869

Cuckle H, Maymon R (2016) Development of prenatal screening—a historical overview. Semin Perinatol 40:12–22. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2015.11.003

Spencer K, Souter V, Tul N et al (1999) A screening program for trisomy 21 at 10–14 weeks using fetal nuchal translucency, maternal serum free beta-human chorionic gonadotropin and pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 13:231–237. doi:10.1046/j.1469-0705.1999.13040231.x

Snijders RJ, Sundberg K, Holzgreve W et al (1999) Maternal age- and gestation-specific risk for trisomy 21. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 13:167–170. doi:10.1046/j.1469-0705.1999.13030167.x

Kagan KO, Wright D, Spencer K et al (2008) First-trimester screening for trisomy 21 by free beta-human chorionic gonadotropin and pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A: impact of maternal and pregnancy characteristics. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 31:493–502. doi:10.1002/uog.5332

Wright D, Kagan KO, Molina FS et al (2008) A mixture model of nuchal translucency thickness in screening for chromosomal defects. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 31:376–383. doi:10.1002/uog.5299

Kagan KO, Wright D, Baker A et al (2008) Screening for trisomy 21 by maternal age, fetal nuchal translucency thickness, free beta-human chorionic gonadotropin and pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 31:618–624. doi:10.1002/uog.5331

Kagan KO, Wright D, Valencia C et al (2008) Screening for trisomies 21, 18 and 13 by maternal age, fetal nuchal translucency, fetal heart rate, free-hCG and pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A. Hum Reprod 23:1968–1975. doi:10.1093/humrep/den224

Wright D, Syngelaki A, Bradbury I et al (2014) First-trimester screening for trisomies 21, 18 and 13 by ultrasound and biochemical testing. Fetal Diagn Ther 35:118–126. doi:10.1159/000357430

Kagan KO, Valencia C, Livanos P et al (2009) Tricuspid regurgitation in screening for trisomies 21, 18 and 13 and Turner syndrome at 11 + 0 to 13 + 6 weeks of gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 33:18–22. doi:10.1002/uog.6264

Kagan KO, Cicero S, Staboulidou I et al (2009) Fetal nasal bone in screening for trisomies 21, 18 and 13 and Turner syndrome at 11–13 weeks of gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 33:259–264. doi:10.1002/uog.6318

Maiz N, Wright D, Ferreira AFA et al (2012) A mixture model of ductus venosus pulsatility index in screening for aneuploidies at 11–13 weeks gestation. Fetal Diagn Ther 31:221–229. doi:10.1159/000337322

Abele H, Wagner P, Sonek J et al (2015) First trimester ultrasound screening for Down syndrome based on maternal age, fetal nuchal translucency and different combinations of the additional markers nasal bone, tricuspid and ductus venosus flow. Prenat Diagn 35:1182–1186. doi:10.1002/pd.4664

Kagan KO, Hoopmann M, Abele H et al (2012) First-trimester combined screening for trisomy 21 with different combinations of placental growth factor, free β-human chorionic gonadotropin and pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 40:530–535. doi:10.1002/uog.11173

Ekelund CK, Petersen OB, Jørgensen FS et al (2015) The Danish fetal medicine database: establishment, organization and quality assessment of the first trimester screening program for trisomy 21 in Denmark 2008–2012. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 94:577–583. doi:10.1111/aogs.12581

Santorum M, Wright D, Syngelaki A et al (2016) Accuracy of first trimester combined test in screening for trisomies 21, 18 and 13. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1002/uog.17283

Kagan KO, Eiben B, Kozlowski P (2014) Kombiniertes Ersttrimesterscreening und zellfreie fetale DNA: next generation screening. Ultraschall Med 35:229–236. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1366353

Kagan KO, Wright D, Etchegaray A et al (2009) Effect of deviation of nuchal translucency measurements on the performance of screening for trisomy 21. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 33:657–664. doi:10.1002/uog.6370

Abele H, Wagner N, Hoopmann M et al (2010) Effect of deviation from the mid-sagittal plane on the measurement of fetal nuchal translucency. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 35:525–529. doi:10.1002/uog.7599

Kagan KO, Avgidou K, Molina FS et al (2006) Relation between increased fetal nuchal translucency thickness and chromosomal defects. Obstet Gynecol 107:6–10. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000191301.63871.c6

Baer RJ, Norton ME, Shaw GM et al (2014) Risk of selected structural abnormalities in infants after increased nuchal translucency measurement. Am J Obstet Gynecol 211(675):e1–e19. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.06.025

Souka AP, Von Kaisenberg CS, Hyett JA et al (2005) Increased nuchal translucency with normal karyotype. YMOB 192:1005–1021. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.093

Merz E, Thode C, Eiben B et al (2011) Individualized correction for maternal weight in calculating the risk of chromosomal abnormalities with first-trimester screening data. Ultraschall Med 32:33–39. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1246001

Wright D, Spencer K, Kagan KK et al (2010) First-trimester combined screening for trisomy 21 at 7–14 weeks’ gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 36:404–411. doi:10.1002/uog.7755

Wright D, Bradbury I, Malone F et al (2010) Cross-trimester repeated measures testing for Down’s syndrome screening: an assessment. Health Technol Assess 14:1–80. doi:10.3310/hta14330

Kagan KO, Etchegaray A, Zhou Y et al (2009) Prospective validation of first-trimester combined screening for trisomy 21. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 34:14–18. doi:10.1002/uog.6412

Pandya P, Wright D, Syngelaki A et al (2012) Maternal serum placental growth factor in prospective screening for aneuploidies at 8–13 weeks’ gestation. Fetal Diagn Ther 31:87–93. doi:10.1159/000335684

Bredaki FE, Wright D, Matos P et al (2011) First-trimester screening for trisomy 21 using alpha-fetoprotein. Fetal Diagn Ther 30:215–218. doi:10.1159/000330198

Gil MM, Accurti V, Santacruz B et al (2017) Analysis of cell-free dna in maternal blood in screening for aneuploidies: updated meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1002/uog.17484

Kagan KO, Hoopmann M, Singer S et al (2016) Discordance between ultrasound and cell free DNA screening for monosomy X. Arch Gynecol Obstet 294:219–224. doi:10.1007/s00404-016-4077-y

Ashoor G, Syngelaki A, Poon LCY et al (2013) Fetal fraction in maternal plasma cell-free DNA at 11–13 weeks’ gestation: relation to maternal and fetal characteristics. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 41:26–32. doi:10.1002/uog.12331

Revello R, Sarno L, Ispas A et al (2016) Screening for trisomies by cell-free DNA testing of maternal blood: consequences of a failed result. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 47:698–704. doi:10.1002/uog.15851

(2015) Committee Opinion No. 640: cell-free DNA screening for fetal aneuploidy. Obstet Gynecol 126:e31–e37. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001051

Wagner P, Sonek J, Hoopmann M et al (2016) First-trimester screening for trisomies 18 and 13, triploidy and Turner syndrome by detailed early anomaly scan. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 48:446–451. doi:10.1002/uog.15829

Grati FR, Kagan KO (2016) No test result rate of cfDNA analysis and its influence on test performance metrics. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1002/uog.17330

Salomon LJ, Alfirevic Z, Audibert F et al (2017) ISUOG updated consensus statement on the impact of cfDNA aneuploidy testing on screening policies and prenatal ultrasound practice. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 49:815–816. doi:10.1002/uog.17483

Nicolaides KH, Wright D, Poon LC et al (2013) First-trimester contingent screening for trisomy 21 by biomarkers and maternal blood cell-free DNA testing. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 42:41–50. doi:10.1002/uog.12511

Wright D, Bradbury I, Benn P et al (2004) Contingent screening for Down syndrome is an efficient alternative to non-disclosure sequential screening. Prenat Diagn 24:762–766. doi:10.1002/pd.974

Kagan K, Schmid M, Hoopmann M et al (2015) Screening performance and costs of different strategies in prenatal screening for trisomy 21. Geburtsh Frauenheilk 75:244–250. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1545885

Beulen L, Faas BHW, Feenstra I et al (2016) The clinical utility of non-invasive prenatal testing in pregnancies with ultrasound anomalies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1002/uog.17228

Grande M, Jansen FAR, Blumenfeld YJ et al (2015) Genomic microarray in fetuses with increased nuchal translucency and normal karyotype: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 46:650–658. doi:10.1002/uog.14880

de Wit MC, Srebniak MI, Govaerts LCP et al (2014) Additional value of prenatal genomic array testing in fetuses with isolated structural ultrasound abnormalities and a normal karyotype: a systematic review of the literature. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 43:139–146. doi:10.1002/uog.12575

Maya I, Yacobson S, Kahana S et al (2017) The cut-off value for normal nuchal translucency evaluated by chromosomal microarray analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1002/uog.17421

Syngelaki A, Guerra L, Ceccacci I et al (2016) Impact of holoprosencephaly, exomphalos, megacystis and high NT in first trimester screening for chromosomal abnormalities. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1002/uog.17286

Everett TR, Chitty LS (2015) Cell-free fetal DNA: the new tool in fetal medicine. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 45:499–507. doi:10.1002/uog.14746

Wapner RJ, Babiarz JE, Levy B et al (2015) Expanding the scope of noninvasive prenatal testing: detection of fetal microdeletion syndromes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 212(332):e1–e9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.11.041

Gammon BL, Kraft SA, Michie M, Allyse M (2016) “I think we’ve got too many tests!”: prenatal providers’ reflections on ethical and clinical challenges in the practice integration of cell-free DNA screening. Ethics Med Public Health 2:334–342. doi:10.1016/j.jemep.2016.07.006

Grati FR, Molina Gomes D, Ferreira JCPB et al (2015) Prevalence of recurrent pathogenic microdeletions and microduplications in over 9500 pregnancies. Prenat Diagn 35:801–809. doi:10.1002/pd.4613

Dugoff L, Mennuti MT, McDonald McGinn DM (2017) The benefits and limitations of cell-free DNA screening for 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Prenat Diagn 37:53–60. doi:10.1002/pd.4864

O’Gorman N, Wright D, Poon LC et al (2017) Accuracy of competing risks model in screening for pre-eclampsia by maternal factors and biomarkers at 11–13 weeks’ gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1002/uog.17399

Vora NL, Robinson S, Hardisty EE, Stamilio DM (2017) Utility of ultrasound examination at 10–14 weeks prior to cell-free DNA screening for fetal aneuploidy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 49:465–469. doi:10.1002/uog.15995

Kenkhuis MJA, Bakker M, Bardi F et al (2017) Yield of a 12–13 week scan for the early diagnosis of fetal congenital anomalies in the cell-free DNA era. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1002/uog.17487

Nicolaides KH, Musci TJ, Struble CA et al (2014) Assessment of fetal sex chromosome aneuploidy using directed cell-free DNA analysis. Fetal Diagn Ther 35:1–6. doi:10.1159/000357198

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KOK, JS, PW, and MH: All four authors have worked together in terms of the project development, manuscript writing, and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This is a review of the actual literature.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kagan, K.O., Sonek, J., Wagner, P. et al. Principles of first trimester screening in the age of non-invasive prenatal diagnosis: screening for chromosomal abnormalities. Arch Gynecol Obstet 296, 645–651 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-017-4459-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-017-4459-9