Abstract

Purpose

To determine the risk of uterine rupture for women undergoing trial of labour (TOL) with both a prior caesarean section (CS) and a vaginal delivery.

Methods

A systematic literature search was performed using keywords for CS and uterine rupture. The results were critically appraised and the data from relevant and valid articles were extracted. Odds ratios were calculated and a pooled estimate was determined using the Mantel–Haenszel method.

Results

Five studies were used for final analysis. Three studies showed a significant risk reduction for women with both a previous CS and a prior vaginal delivery (PVD) compared to women with a previous CS only, and two studies showed a trend towards risk reduction. The absolute risk of uterine rupture with a prior vaginal delivery varied from 0.17 to 0.46%. The overall odds ratio for PVD was 0.39 (95% CI 0.29–0.52, P < 0.00001).

Conclusion

Women with a history of both a CS and vaginal delivery are at decreased risk of uterine rupture when undergoing TOL compared with women who have only had a CS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Traditionally the Netherlands have a low rate of caesarean sections (CS), but this rate has risen from 8% in 1993 to 15.1% in 2007 [1]. One of the reasons for this increase is that the higher rates of maternal and neonatal complications are reported [2, 3] for women undergoing trial of labour (TOL) after a first caesarean section. One of the most serious complications is the rupture of the uterus [4]. In general, the success rate of TOL is approximately 75% [5] and the associated risk of uterine rupture 0.4–0.7% [4, 6–8]. This risk increases when there is a classical or lower uterine segment vertical incision scar [9–12], or when labour is induced using oxytocin [13–15] or prostaglandins [7, 15, 16]. A risk reduction [17, 18] has been described for women with a prior vaginal delivery (PVD); however, no systematically reviewed data exist concerning the magnitude of the effect. This may play an important role in the decision whether to initiate TOL. Therefore, the aim of our study is to perform a systematic literature review to determine the risk of uterine rupture for women with a history of both a caesarean section and a vaginal delivery.

Methods

Search strategy

A literature review was conducted in the Medline database using the Pubmed search engine as well as in the Embase database, the Cochrane library and CINAHL. We conducted the search using keywords for the patient population and outcome, see Table 1.

We used the following exclusion criteria: articles not in English, Dutch or German, case reports or no full text available. Inclusion criteria were that the study population included women with a history of caesarean section, a prior vaginal delivery and uterine rupture as an outcome measure. The search was conducted in June 2010. To assess the eligibility of the studies, two authors independently appraised and cross-checked the extracted studies. The included studies were screened for related articles.

Critical appraisal

The resulting articles were more closely looked at in the critical appraisal. Both the relevance and validity were evaluated. Studies were deemed relevant when patient population, predictor and outcome measures were in accordance with the predefined criteria as outlined in Table 2. To evaluate the validity, a set of criteria was established to rate the included studies on study design, selection bias, study size and outcome measures. To determine the criterion of population size, an a priori power analysis was conducted. For all criteria used, see Table 2. The level of evidence was graded according to the Harbour and Miller criteria [19], but this was not used as an independent criterion. Studies with both moderate to good relevance and validity were used to answer the clinical question.

Statistical analysis

Data on rates of uterine rupture in women with a history of both a CS and a PVD versus women with a history of solely a CS were extracted from the included studies. For one study [5], the original dataset was used in addition to the published article. The data were subsequently summarized in 2 × 2 tables. Where needed, missing values were computed on the basis of odds ratios and sample sizes using the quadratic formula. Statistical analysis was performed using RevMan 5 software [20]. Results were aggregated using the Mantel–Haenszel method [21] for fixed effects models, and the odds ratio of the pooled data was calculated with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Search

The search query returned 3,578 articles across all search engines. Screening the results based on title and abstract resulted in 54 articles. Upon examination of the full text article, 9 articles were selected for further appraisal. Additionally one related article was found, see Fig. 1.

Critical appraisal

Ten articles [9, 22–29] were assessed in the critical appraisal. The criteria for the critical appraisal are outlined in Table 2. Six studies were selected, five of which were used for final analysis. All of them were cohort studies, three retrospective and two prospective. Population size varied from 2,204 to 35,854 patients. Four studies included women with a single caesarean section, while Kwee 2007 used one or more caesarean section as criterion. Hendler 2004 used a single previous vaginal delivery as predictor whereas the rest used one or more vaginal deliveries. The outcome measure was clinically evident uterine rupture for all studies. Although it is not explicitly stated that the dataset in Grobman 2008 is identical to the dataset in Grobman 2007 [23], presumably the same population is described. The data from Grobman 2008 [24] were, therefore, not used in further analysis.

Mercer [27] and Shimonovitz [30] were excluded since they studied a prior vaginal birth after caesarean section (VBAC) instead of any previous vaginal delivery as predictor. In addition, the study by Shimonovitz et al. [30] was a case control study by design and the definition of uterine rupture was not clearly described. Similarly, Bedoya et al. [22] did not feature a clear definition, was retrospective in design and the population size was not adequate. The study by Macones et al. [26] was a case–control study in which patients with one or more CS were included. Moreover, one or more PVD instead of only a single PVD was used as predictor.

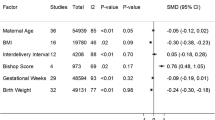

Prior vaginal delivery and uterine rupture

All studies found a lower risk of uterine rupture for women with a previous PVD, three studies showing a significant risk reduction and two studies showing a strong trend. Odds ratios varied from 0.18 (Zelop et al. [29]) to 0.47 (Kwee et al. [5]), with an absolute risk of uterine rupture with a PVD varying from 0.17% (Smith et al. [28]) to 0.82% (Kwee et al. [5]). When the results are pooled, the combined OR is 0.39 (95% CI 0.29–0.52, P < 1 × 10−10), see Fig. 2. Results are summarized in Table 3.

Discussion

Faced with choosing an intended route of delivery after a low-transverse caesarean section, women must choose between an elective caesarean section, with increased maternal morbidity on the short term and more long-term reproductive consequences [6, 31] and TOL, which involves a concurrent higher risk of uterine rupture. In order to make an informed decision, pregnant women with a previous caesarean delivery must be made aware of this risk of uterine rupture.

This systematic review of the literature has shown a previous vaginal delivery for women with a prior caesarean section, to be strongly predictive for the risk of uterine rupture, associated with a risk reduction of more than 60%. The evidence for this effect is strong due to the fact that the studies included have a relatively large sample size and because all studies are consistent in showing an effect in the same direction and of about the same magnitude. All but two studies showed a statistically significant effect. The pooled data showed a cumulative OR of 0.39.

It must be noted, however, that the analyzed studies, except for Hendler et al. [25], used one or more previous vaginal delivery as the predictor. This could have possibly augmented the found effect. Shimonovitz et al. [30], however, examined the effect of multiple VBAC attempts on the risk of uterine rupture and found no additional effect of two or more VBAC attempts. Mercer et al. [27] confirmed this finding. It is, therefore, unlikely that an increased number of previous vaginal deliveries will have a substantial additional effect.

Most of the data in Table 3 have been calculated using data extracted from the studies. Smith et al. [28] and presumably Hendler et al. [25] provided adjusted odds ratios. By means of comparing results and using previous vaginal delivery as an isolated predictor, unadjusted odds ratios needed to be calculated. It is conceivable that there are confounding factors present and, therefore, no conclusions can be drawn about a causative relation of PVD status with uterine rupture. However, this has no bearing on the usefulness of PVD status as an isolated predictor, which was the aim of this review.

Regarding the order of the caesarean section and the prior vaginal delivery, no data are available on its effect on the rate of uterine rupture. However, higher success rates for TOL are reported after a prior successful VBAC when compared with a vaginal delivery before the caesarean section [14, 32, 33]. It may, therefore, be conceivable that the risk of uterine rupture is lower for women who had a successful delivery after a caesarean section, in comparison to those who had a vaginal delivery prior to the caesarean section.

The abovementioned findings will be relevant for multiparae who have undergone a CS in the last pregnancy, as we have shown that a previous PVD is associated with a strongly reduced risk for uterine rupture and a high chance of success for TOL. Moreover, implications may extend to those women who had a CS in their first pregnancy and have to choose a delivery route for further pregnancies. The increased risk of placenta accreta and placenta praevia [34, 35] with each additional CS and the decreased risk of uterine rupture after VBAC, may be a reason to choose for TOL for families who plan on having more than two children.

Conclusion

Considering on the one hand the high quality of the evidence for PVD status as predictor for lower risk of uterine rupture, and on the other the severe consequences of uterine rupture for both mother and child, we strongly recommend the use of PVD status for deciding the intended delivery route.

References

Prismant BV (2008) Landelijke Verloskundige Registratie (Dutch Perinatal Database) Stichting Perinatale Registratie

McMahon MJ, Luther ER, Bowes WA, Olshan AF (1996) Comparison of a trial of labor with an elective second cesarean section. N Engl J Med 335:689–695

Smith GCS, Pell JP, Cameron AD, Dobbie R (2002) Risk of perinatal death associated with labor after previous cesarean delivery in uncomplicated term pregnancies. JAMA 287:2684–2690

Zwart JJ, Richters JM, Öry F, de Vries JIP, Bloemenkamp KWM, van Roosmalen J (2009) Uterine rupture in the Netherlands: a nationwide population-based cohort study. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 116:1069–1080

Kwee A, Bots ML, Visser GH, Bruinse HW (2007) Obstetric management and outcome of pregnancy in women with a history of caesarean section in the Netherlands. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 132:171–176

Landon MB, Hauth JC, Leveno KJ, Spong CY, Leindecker S et al (2004) Maternal and perinatal outcomes associated with a trial of labor after prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med 351:2581–2589

Lydon-Rochelle M, Holt VL, Easterling TR, Martin DP (2001) Risk of uterine rupture during labor among women with a prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med 345:3–8

Mozurkewich EL, Hutton EK (2000) Elective repeat cesarean delivery versus trial of labor: a meta-analysis of the literature from 1989 to 1999. Am J Obstet Gynecol 183:1187–1197

O’Brien-Abel N (2003) Uterine rupture during VBAC trial of labor: risk factors and fetal response. J Midwifery Women’s Health 48:249–257

Martin JN Jr, Perry KG Jr, Roberts WE, Meydrech EF (1997) The case for trial of labor in the patient with a prior low-segment vertical cesarean incision. Am J Obstet Gynecol 177:144–148

Rosen MG, Dickinson JC, Westhoff CL (1991) Vaginal birth after cesarean: a meta-analysis of morbidity and mortality. Obstet Gynecol 77:465–470

Halperin ME, Moore DC, Hannah WJ (1988) Classical versus low-segment transverse incision for preterm caesarean section: maternal complications and outcome of subsequent pregnancies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 95:990–996

Flamm BL, Geiger AM (1997) Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery: an admission scoring system. Obstet Gynecol 90:907–910

Leung AS, Farmer RM, Leung EK, Medearis AL, Paul RH (1993) Risk factors associated with uterine rupture during trial of labor after cesarean delivery: a case-control study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 168:1358–1363

Zelop CM, Shipp TD, Repke JT, Cohen A, Caughey AB, Lieberman E (1999) Uterine rupture during induced or augmented labor in gravid women with one prior cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 181:882–886

Ravasia DJ, Wood SL, Pollard JK (2000) Uterine rupture during induced trial of labor among women with previous cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 183:1176–1179

Harper LM, Macones GA (2008) Predicting success and reducing the risks when attempting vaginal birth after cesarean. Obstet Gynecol Surv 63:538–545

Smith GCS, White IR, Pell JP, Dobbie R (2005) Predicting cesarean section and uterine rupture among women attempting vaginal birth after prior cesarean section. PLoS Med 2:e252

Harbour R, Miller J (2001) A new system for grading recommendations in evidence based guidelines. BMJ 323:334–336

The Cochrane Collaboration OUK (2009). RevMan 5

Mantel N, Haenszel W (1959) Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst 22:719–748

Bedoya C, Bartha JL, Rodriguez I, Fontan I, Bedoya JM, Sanchez-Ramos J (1992) A trial of labor after cesarean section in patients with or without a prior vaginal delivery. Int J Gynecol Obstet 39:285–289

Grobman WA, Gilbert S, Landon MB, Spong CY, Leveno KJ et al (2007) Outcomes of induction of labor after one prior cesarean. Obstet Gynecol 109:262–269

Grobman WA, Lai Y, Landon MB, Spong CY, Leveno KJ et al (2008) Prediction of uterine rupture associated with attempted vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 199:e1–e30

Hendler I, Bujold E (2004) Effect of prior vaginal delivery or prior vaginal birth after cesarean delivery on obstetric outcomes in women undergoing trial of labor. Obstet Gynecol 104:273–277

Macones GA, Peipert J, Nelson DB, Odibo A, Stevens EJ et al (2005) Maternal complications with vaginal birth after cesarean delivery: a multicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 193:1656–1662

Mercer BM, Gilbert S, Landon MB, Spong CY, Leveno KJ et al (2008) Labor outcomes with increasing number of prior vaginal births after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 111:285–291

Smith GCS, Pell JP, Pasupathy D, Dobbie R (2004) Factors predisposing to perinatal death related to uterine rupture during attempted vaginal birth after caesarean section: retrospective cohort study. Br Med J 329:375–377

Zelop CM, Shipp TD, Repke JT, Cohen A, Lieberman E (2000) Effect of previous vaginal delivery on the risk of uterine rupture during a subsequent trial of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol 183:1184–1186

Shimonovitz S, Botosneano A, Hochner-Celnikier D (2000) Successful first vaginal birth after cesarean section: a predictor of reduced risk for uterine rupture in subsequent deliveries. Isr Med Assoc J 2:526–528

Pare E, Quinones JN, Macones GA (2006) Vaginal birth after caesarean section versus elective repeat caesarean section: Assessment of maternal downstream health outcomes. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 113:75–85

Gyamfi C, Juhasz G, Gyamfi P, Stone JL (2004) Increased success of trial of labor after previous vaginal birth after cesarean. Obstet Gynecol 104:715–719

Weinstein D, Benshushan A, Tanos V, Zilberstein R, Rojansky N (1996) Predictive score for vaginal birth after cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol 174:192–198

Kwee A, Bots ML, Visser GHA, Bruinse HW (2006) Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: a prospective study in The Netherlands. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 124:187–192

Silver RM, Landon MB, Rouse DJ, Leveno KJ, Spong CY et al (2006) Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol 107:1226–1232

Conflict of interest

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

de Lau, H., Gremmels, H., Schuitemaker, N.W. et al. Risk of uterine rupture in women undergoing trial of labour with a history of both a caesarean section and a vaginal delivery. Arch Gynecol Obstet 284, 1053–1058 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-011-2048-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-011-2048-x