Abstract

Purpose

It is difficult to change dietary habits and maintain them in the long run, particularly in elderly people. We aimed to assess whether adherence to the Mediterranean diet (MedDiet) and cardiovascular risk factor were similar in the middle-aged and oldest participants in the PREDIMED study.

Methods

We analyzed participants belonging to the first and fourth quartiles of age (Q1 and Q4, respectively) to compare between-group differences in adherence to the nutritional intervention and cardiovascular risk factor (CRF) control during a 3-year follow-up. All participants underwent yearly clinical, nutritional, and laboratory assessments during the following.

Results

A total of 2278 patients were included (1091 and 1187 in Q1 and Q4, respectively). At baseline, mean ages were 59.6 ± 2.1 years in Q1 and 74.2 ± 2.6 years in Q4. In Q4, there were more women, greater prevalence of hypertension and diabetes, and lower obesity and smoking rates than the younger cohort (P ≤ 0.001, all). Adherence to the MedDiet was similar in Q1 and Q4 at baseline (mean 8.7 of 14 points for both) and improved significantly (P < 0.01) and to a similar extent (mean 10.2 and 10.0 points, respectively) during follow-up. Systolic blood pressure, low density–lipoprotein cholesterol, and body weight were similarly reduced at 3 years in Q1 and Q4 participants.

Conclusion

The youngest and oldest participants showed improved dietary habits and CRFs to a similar extent after 3 years’ intervention. Therefore, it is never too late to improve dietary habits and ameliorate CRF in high-risk individuals, even those of advanced age.

Registration

The trial is registered in the London-based Current Controlled Trials Registry (ISRCTN number 35739639).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) has the highest incidence and prevalence in elderly persons, in whom it is associated with high morbidity and mortality [1, 2]. In Europe, CVD incidence is predicted to increase in the near future because of population ageing [3, 4]. In addition, the elderly frequently suffer multimorbidities, and a significant proportion can be classified as frail [5]. Frailty shares some physiopathological mechanisms with CVD and both conditions are tightly interrelated, as frailty can worsen CVD and CVD may precipitate frailty [6, 7]. A healthy dietary pattern, such as the Mediterranean diet (MedDiet) is associated with both lower rates of non-communicable diseases, including CVD [8, 9] and frailty [10, 11].

CVD is a main component of multimorbidity, and may be prevented and managed by pharmacological and non-pharmacologic therapies, such as a healthy diet, increased physical activity, and abstention from smoking [12]. In fact, lifestyle changes are the cornerstone of CVD prevention and are recommended in all international guidelines [12, 13]. The main problem with lifestyle measures is that a change in patient behaviour is mandatory to transform unhealthy habits to healthy ones and maintain them in the long run, which is particularly difficult in the elderly, due to several factors such as lower appetite, food changes, declining physical function, cooking for one, shopping for one, food cost, etc. [14,15,16,17].

The PREvención con DIeta MEDiterránea (PREDIMED) randomized trial demonstrated that a MedDiet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil (EVOO) or mixed nuts can improve cardiovascular risk factor (CRF) control [18, 19] and reduce CVD incidence by nearly 30% in older individuals at high cardiovascular risk compared to advice on a low-fat diet (LFD) [9]. However, it is unknown whether adherence to the MedDiet was similar in the youngest and oldest participants in the PREDIMED trial and also whether the beneficial effect on CRFs differed in younger and older individuals, since in a previous PREDIMED study, short and long-term predictors of dietary changes were analyzed, but age was not a clear predictor in either of these two analyses [17].

Materials and methods

Study participants and design

The PREDIMED study (www.predimed.es) was a nutritional intervention–based randomized trial, single-blind, multicenter (11 centres throughout Spain) study carried out on 7447 participants at high vascular risk, but no CVD at enrolment, conducted from October 2003 to December 2010. The aim of this primary prevention study was to assess the long-term effects of the MedDiet on incident CVD in men and women aged 55–80 years at high CVD risk. The protocol, methods, design, and eligibility criteria for this study have been reported in detail elsewhere [9]. Briefly, participants were assigned to one of three nutritional interventions by a computer-generated random-number sequence: a traditional MedDiet supplemented with either complementary EVOO or tree nuts and a control diet based on advice to follow an LFD.

In the current study, we analyzed data of participants belonging to the first (n = 1091) and fourth (n = 1187) quartiles of baseline age to compare dietary intake, adherence to the nutritional interventions, and CRF control. We included a total of 2278 participants with complete information on food consumption and nutrient intake, adiposity, and CRFs at baseline and after 3 years of follow-up.

Assessments and intervention

Throughout the study, participants in the MedDiet groups had face-to-face interviews with a dietitian (yearly) and at group sessions (every 3 months) in which they received instructions and written material with information on seasonal Mediterranean foods, shopping lists, weekly meal plans, and cooking recipes for a typical week. They were instructed to follow the allocated diets, with different sessions for each intervention group. During the group sessions with dietitians and according to treatment allocation, participants in the two MedDiet groups were provided with either 1 L per week of EVOO (to consume at least 50 mL/day) or mixed nuts (30 g/day: 15 g walnuts, 7.5 g hazelnuts, and 7.5 g almonds) at no cost. Participants in the LFD group also had individual and group sessions quarterly with the dietitian, were given information and written material on the LFD (according to the American Heart Association guidelines), and received non-food gifts. None of the three groups received advice on energy restriction or promotion of physical activity.

A validated 14-point MedDiet screener was used to assess adherence to the MedDiet [20], while a nine-item questionnaire was used to evaluate adherence to the LFD [9]. Also, at baseline and yearly during follow-up, dietitians administered in face-to-face interviews a 137-item validated food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ) [21], used to assess energy and nutrients using Spanish food-composition tables [22]. The Minnesota Leisure Time Physical Activity Questionnaire and a 47-item questionnaire on education, lifestyle, history of illnesses, and medication use were also administered at baseline and yearly.

Clinical measurements

Trained personnel performed anthropometric measurements. Height and weight of volunteers were measured using a wall‐mounted stadiometer and calibrated scales, respectively. Waist circumference was measured midway between the lowest rib and the iliac crest using an anthropometric tape. Blood pressure (BP) was measured in triplicate with a validated semiautomatic oscillometer (Omron HEM-705CP, Hoofddorp, Netherlands).

In addition, fasting blood and spot urine were obtained and plasma, serum, and buffy coats stored at − 80 °C until assay. The analytes determined in frozen samples of serum or plasma as appropriate were glucose by the glucose oxidase method, cholesterol and triglyceride by standard enzymatic procedures, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol after precipitation with phosphotungstic acid and magnesium chloride, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol by the Friedewald formula when triglycerides were < 400 mg/dL.

Ethics statement

All participants provided written informed consent to a protocol designed according to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki that had been approved by the institutional review boards of all participating centres. The Institutional Review Board of the Hospital Clinic (Barcelona, Spain), accredited by the US Department of Health and Human Services update for Federalwide Assurance for the Protection of Human Subjects for International (non-US) Institutions (00000738), approved the study protocol on July 16, 2002. The trial was registered (ISRCTN35739639).

Statistical analyses

Subjects were stratified into quartiles of age. The first quartile comprised participants ≤ 62 years old (youngest) and the fourth quartile those ≥ 71 years old (oldest). Baseline characteristics of the participants are expressed as means ± SD) or percentages as appropriate. Kolmogorov and Levene tests were used to assess data normality and skewness. One-factor ANOVA with two factors (treatment group and age quartiles 1–4) was used for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. Analysis of the effects of treatment and age quartile (Q1 vs Q4) was performed using ANOVA for analysis of the baseline visit and ANCOVA adjusted for change from baseline at 3 years. For changes in scores on the 14-item questionnaire of Mediterranean diet adherence in extreme quartiles of age, we used χ2 for comparisons between age groups, diet groups, changes between age groups, changes between diet groups. We also used the McNemar test to compare between baseline and 3-year values. Analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0. Significance level was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Study population

Of the 7447 participants included, we analyzed data of 2278 with complete information on food consumption, nutrient intake, adiposity, and CRFs at baseline and after 3 years of follow-up (Fig. 1). The first (≤ 62 years, mean 59.6 ± 2.1 years) and fourth (≥ 71 years, mean 74.3 ± 2.6 years) age quartiles were composed of 1091 and 1187 subjects. Baseline characteristics of these participants are summarised in Table 1.

In Q4, there were more women, greater prevalence of hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus, and lower prevalence of dyslipidemia, overweight/obesity, smoking, and family history of ischemic heart disease than participants in Q1 (P ≤ 0.006, all). With regard to medication, older participants took more angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors, oral hypoglycaemic drugs, aspirin or other antiaggregants, antidepressants, diuretics, vitamins, or supplements than younger subjects (P < 0.05, all). In Q1 and Q4, participants in the control group (LFD) took more antidepressants and diuretics than those in the two MedDiet groups (P < 0.05, both).

Adherence to MedDiet based on the 14-item questionnaire

As expected, both Q1 and Q4 participants allocated to the MedDiet groups significantly improved MedDiet adherence on 13 of 14 score items (Supplementary Table 1). Almost all participants (~ 97%) in the MedDiet groups used OO as their main culinary fat, whereas this percentage was lower (~ 93%) in the control group (P < 0.001, both). At the end of the 3-year-intervention, ≥ 75% of participants in the MedDiet groups had appropriate intake of red meat, butter, carbonated beverages, chicken, turkey, rabbit, fish, shellfish, and dishes dressed with sofrito, while optimal daily consumption of fruit and vegetables was achieved by only 60% of the participants.

These changes brought patients' diets closer to the MedDiet pattern. In fact, after 3 years of intervention, > 75% of participants allocated to the two MedDiet groups fulfilled the criteria for eight of the 14 items evaluated in our MedDiet questionnaire. Dietary improvement was lower in the control group than the MedDiet groups, and consisted mainly in decreased consumption of red meat and butter and moderate increases in vegetables, fish, and white meat (P < 0.05, all).

Changes in intake of selected foods and physical activity

As shown in Table 2, at the 3-year follow-up, MedDiet-adherence scores were greater (about 1.6–2 points) in Q1 and Q4 participants in both MedDiet groups than those in the LFD group (P < 0.001). Adherence to the MedDiet intervention was similar between the youngest and oldest PREDIMED participants at the end of the intervention.

In addition, the two MedDiet groups showed good adherence to the supplemented foods (EVOO or nuts, P ≤ 0.001 for both), which was slightly higher in younger than older (P ≤ 0.065, both) participants. Both the Q1 and Q4 groups showed increased consumption of fruit and legumes and decreased consumption of meat and meat products and cereals. Consumption of pastries, cakes, sweets, and alcohol had significantly reduced in both groups (Q1 and Q4, P ≤ 0.012, all). In comparison with Q4, participants in Q1 showed significantly increased consumption of vegetables, fish, seafood, tea, and coffee and significantly decreased consumption of milk and dairy products (P < 0.05, all).

However, the MedDiet groups in Q1 and Q4 differed in some specific foods. As such, these groups reported higher consumption of fruit, legumes, fish and seafood than the control group (P ≤ 0.025, all). In addition, the Q1 group disclosed higher consumption of vegetables and tea (P < 0.05, both) than the Q4 group, while the latter group had higher consumption of milk and dairy products (P = 0.032).

Finally, only participants in the Q1 group had significantly increased their physical activity during follow-up, which was significantly higher than those in Q4 (P < 0.001). On the other hand, Q4 participants in the control group had significantly decreased physical activity (P < 0.05).

Changes in energy and nutrient intake in young and old cohorts

The Q1 and Q4 groups had significantly decreased consumption of cholesterol and calcium at the end of the study (P ≤ 0.007). Participants in Q1 had increased intake of magnesium in comparison to Q4 (P = 0.051), while participants in Q4 had higher reductions in sodium than participants in Q1 (P = 0.08). On the other hand, consumption of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs; P < 0.001), α-linolenic acid (P < 0.001), and marine n-3 FAs (P ≤ 0.002) had increased during the study period in both quartiles (Table 3).

Q1 and Q4 subjects in the two MedDiet groups had reduced consumption of protein intake, total carbohydrates, saturated FAs (SFAs), potassium, and sodium (P < 0.05, all) and increased consumption of fibre, monounsaturated FAs (MUFAs), α-linolenic acid, and marine n-3 FAs (P < 0.001, all). In addition, Q1 and Q4 participants on the MedDiet supplemented with nuts had increased consumption of α-linolenic acid and magnesium (P < 0.001, both). On the other hand, for the LFD in both Q1 and Q4, there were significant reductions in energy, total fat, and calcium intake (P < 0.001). Finally, Q1 participants in the two MedDiet groups showed significantly increased PUFAs (P < 0.001).

Changes in classical cardiovascular risk factors

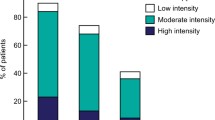

As represented in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2, systolic BP and HDL-cholesterol levels had decreased in both quartiles (P ≤ 0.002, both) at 3 years, although the change was greater in the Q1 group. In addition, modest reductions in body weight and (P < 0.05) occurred in both quartiles, slightly superior in Q4 (P ≤ 0.04). Likewise, a reduction in serum LDL-cholesterol (P = 0.030) was observed in Q1 and Q4 subjects, although this reduction was higher in the Q4 group. Finally, it is noteworthy that diastolic BP had decreased in Q4, contrary to Q1, whose BP had increased (P < 0.001 and Pinteraction = 0.01). No significant differences were observed in serum triglycerides, fasting blood glucose, or waist circumference.

Changes in cardiovascular risk factors after 3 years of nutritional nutrition stratified by extreme quartiles of age. The analysis of the effect of the treatment group and the Quartile of Age (Q1 vs Q4) were performed by ANOVA for the analysis of the baseline visit and by ANCOVA adjusted with the baseline values for the change at 3 years. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 indicates statistical significance by t-test for related samples. BMI body mass index, DBP diastolic blood pressure, HDL high density lipoprotein, LDL low density lipoprotein, SBP systolic blood pressure

Discussion

The present results show that adherence to the nutritional intervention implemented in the PREDIMED trial was similar between older (Q4, ≥ 71 years old) and younger (Q1, ≤ 62 years old) participants and was maintained throughout a 3-year follow-up. Both cohorts had increased their scores on the 14-item MedDiet questionnaire by 1.6–2 points at the end of the intervention. As a result, improvement in CRF control was also similar in the two groups. In concordance, subgroup analyses on the primary outcome of the PREDIMED trial also revealed similar CVD-risk reduction with the MedDiet in participants aged < 70 years and ≥ 70 years [9].

While comparisons of dietary intake and MedDiet adherence with younger participants was not possible due to inclusion criteria (aged 55–80 years), some differences has been observed. Although younger and older subjects reached similar overall adherence to the MedDiet (10.1 vs 10.0 of 14 points, respectively), some between-group differences deserve to be mentioned. At the end of the intervention, a lower proportion of Q4 participants had achieved recommended doses of OO, nuts, fruit, legumes, and commercial sweets, while a higher percentage had reached recommended doses of red meat, dietary milk, and alcohol than Q1 participants.

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and other epidemiological studies have revealed that intake of beneficial nutrients, such as complex carbohydrates, fibre, MUFAs, and PUFAs, is reduced in older individuals, while intake of unhealthy nutrients, such as SFAs, is increased [23,24,25]. Data from our study showed that independently of age, allocation to the two MedDiet groups resulted in significant reductions in SFA intake and increased intake of MUFA and fibre, while PUFA intake increased only in participants allocated to the MedDiet supplemented with nuts. Higher fibre intake can be related to healthy dietary changes, such as higher consumption of fruit, vegetables, legumes, and nuts. In fact, higher intake of MUFAs, PUFAs, and fibre can have a protective effect against such age-related disorders as cognitive decline, CVD, diabetes, and cancer, as well as development of frailty [8,9,10,11, 18, 26,27,28,29,30]. Furthermore, it should be noted that while both MedDiet groups from the Q4 group significantly increased marine ω3 FA intake, only those allocated to the MedDiet supplemented with nuts significantly increased α-linolenic intake, as expected from the richness of walnuts in this FA. Importantly, intake of long-chain PUFAs, such as marine ω3 FAs and α-linolenic acid, is associated with improved cognition and reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias [28, 29, 31].

Ageing is frequently associated with malnutrition, particularly in frail individuals, due to such factors as hyporexia, decreased saliva production, disturbances in taste and smell, and biological changes, such as alterations in ghrelin and cholecystokinin production, as well as polypharmacy effects [14, 16]. Epidemiological studies have shown that compared to young people, the average daily caloric intake is lower in the elderly by approximately 1000 and 700 kcal/day in men and women, respectively [24]. Also, an observational study reported that a significant proportion of persons aged > 80 years had a daily energy intake < 20 kcal/kg body weight [32]. However, in our study, daily energy intake at the end of the study was lower in Q1 and Q4 participants in the LFD group than the two MedDiet groups, whose intake of protein and fat was maintained or even increased. In other reports on elderly people, animal-protein intake was reduced, which was attributed in part to difficulty chewing and swallowing [33]. It is well established that old people must maintain adequate daily protein intake as a preventive measure to preserve skeletal muscle mass and avoid sarcopenia and frailty [34].

As stated in most guidelines, non-pharmacological measures are the first therapeutic approach to improve control of CRFs and reduce incidence of CVD [5, 12, 13]. However, there is concern whether elderly persons are capable of improving unhealthy lifestyle habits and maintaining beneficial changes in the long run, probably because changes associated with ageing, such as loss of appetite (reduced taste and smell), loneliness, eating alone, depression, and low income, can influence food choices and dietary habits [14,15,16]. The usefulness of non-pharmacological measures to reduce CVD incidence or improve nutritional status in elderly people has recently been reviewed [35]. While the evidence is of low quality, because it was based on heterogeneous results obtained from small cohorts with short follow-up periods [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42], the results are encouraging. Adherence to a MedDiet intervention for 6 months in a cohort of 166 elders (mean age 71 years) was high (85%) and associated with lower BP and improvement in endothelial function [36]. Likewise, adherence to a DASH diet for ≤ 3 months in two cohorts of aged Asian individuals was also high and resulted in lower BP [37,38,39]. Also, a multicomponent nutritional telemonitoring intervention applied for 6 months in elderly people (mean age 78 years) at risk of undernutrition showed good adherence and resulted in improved diet quality and nutritional status [40]. The NU-AGE project conducted on a cohort of 1141 elderly European subjects demonstrated that it is possible to change dietary habits of elders towards a healthier diet that can improve cognitive and bone health [41]. On the other hand, regarding physical activity, preliminary data from the PREDIMED-Plus study have revealed that it is also feasible to increase physical activity in old people in the long run (12 months) [42], which confirms findings from a recent meta-analysis [43]. Other studies, however, have shown negative results [44, 45].

Our study has strengths, such as the clinical trial design, repeated data collection, validated FFQ, standardized measurements of clinical and nutritional variables, a relatively large sample (2200 patients), and long-follow-up (3 years). The main limitations are the use of the FFQ may have led to a misclassification of the exposure due to an overestimation of food intake and the fact that dietary data are self-reported. In addition, self-reported questionnaires about diet, physical activity and other medical data can lead to misclassification, which would attenuate the association of the exposure variables with the outcome. Furthermore, potential residual confounding and the lack of generalizability of the results to other populations are limitations in this study. Unmeasured confounders may have distorted results for predictors of dietary adherence, though analyses were adjusted for a wide array of confounders, and a strong confounder unrelated to these characteristics is unlikely. Finally, the findings in our Mediterranean cohort of individuals at high cardiovascular risk cannot easily be extrapolated to other populations.

Conclusion

We report that persons aged > 70 years can improve their dietary habits and adhere in the long term to an enhanced MedDiet in a similar way to younger adult individuals. This goal was reached in part because participants were taught and trained with high intensity by motivated dietitians and received key MedDiet foods for free. As a healthy and high-quality diet, the MedDiet was associated with reduced potency of CRFs to a similar extent in elderly and younger individuals. The benefits of the MedDiet for non-communicable diseases include reduced rates of diabetes and some cancers, lower BP, and improved cognition, as described in other PREDIMED reports [18, 19, 29, 30]. The take-home message is that we should not miss the opportunity to apply such non-pharmacological measures as the MedDiet, which has high efficacy without adverse effects, to improve the overall health of aged people. It is never too late to change dietary habits to achieve healthy ageing.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body-mass index

- CHD:

-

Coronary heart disease

- CRF:

-

Cardiovascular risk factor

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- EVOO:

-

Extra-virgin olive oil

- FFQ:

-

Food-frequency questionnaire

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein

- LDL:

-

Low-density lipoprotein

- LFD:

-

Low-fat diet

- MedDiet:

-

Mediterranean diet

- MUFAs:

-

Monounsaturated fatty acids

- PUFAs:

-

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

- PREDIMED:

-

Prevention with Mediterranean Diet

- SFAs:

-

Saturated FAs

References

Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A et al (2017) Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases for 10 causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol 70:1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.052

Cardiovascular diseases. https://www.who.int/health-topics/cardiovascular-diseases/#tab=tab_1. Accessed 27 May 2020

Population structure and ageing—statistics explained. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Population_structure_and_ageing. Accessed 27 May 2020

Ageing | United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/ageing/. Accessed 27 May 2020

Abraha I, Cruz-Jentoft A, Soiza RL et al (2015) Evidence of and recommendations for non-pharmacological interventions for common geriatric conditions: The SENATOR-ONTOP systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007488

Stewart R (2019) Cardiovascular disease and frailty: what are the mechanistic links? Clin Chem 65:80–86. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2018.287318

Veronese N (2020) Frailty as cardiovascular risk factor (and vice versa). Advances in experimental medicine and biology. Springer, pp 51–54

Dinu M, Pagliai G, Casini A, Sofi F (2018) Mediterranean diet and multiple health outcomes: an umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised trials. Eur J Clin Nutr 72:30–43

Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J et al (2018) Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. N Engl J Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1800389

Struijk EA, Hagan KA, Fung TT et al (2020) Diet quality and risk of frailty among older women in the Nurses’ Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr 111:877–883. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa028

Kojima G, Avgerinou C, Iliffe S, Walters K (2018) Adherence to Mediterranean diet reduces incident frailty risk: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 66:783–788. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15251

Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C et al (2016) 2016 European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106

Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA et al (2019) 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 140:e596–e646. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678

Whitelock E, Ensaff H (2018) On your own: older adults’ food choice and dietary habits. Nutrients. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10040413

Donini LM, Savina C, Cannella C (2003) Eating habits and appetite control in the elderly: the anorexia of aging. Int Psychogeriatr 15:73–87

Yannakoulia M, Mamalaki E, Anastasiou CA et al (2018) Eating habits and behaviors of older people: where are we now and where should we go? Maturitas 114:14–21

Downer MK, Gea A, Stampfer M et al (2016) Predictors of short- and long-term adherence with a Mediterranean-type diet intervention: the PREDIMED randomized trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-016-0394-6

Estruch R, Martínez-González MA, Corella D et al (2006) Effects of a Mediterranean-style diet on cardiovascular risk factors a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 145:1–11. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-145-1-200607040-00004

Martínez-González MA, Salas-Salvadó J, Estruch R et al (2015) Benefits of the Mediterranean diet: insights from the PREDIMED study. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 58:50–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2015.04.003

Schröder H, Fitó M, Estruch R et al (2011) A short screener is valid for assessing Mediterranean diet adherence among older Spanish men and women. J Nutr 141:1140–1145. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.110.135566

Fernández-Ballart JD, Piñol JL, Zazpe I et al (2010) Relative validity of a semi-quantitative food-frequency questionnaire in an elderly Mediterranean population of Spain. Br J Nutr 103:1808–1816. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114509993837

Tablas de composición de alimentos (Mataix et al.). http://www.sennutricion.org/en/2013/05/11/tablas-de-composicin-de-alimentos-mataix-et-al. Accessed 27 May 2020

Ter Borg S, Verlaan S, Mijnarends DM et al (2015) Macronutrient intake and inadequacies of community-dwelling older adults, a systematic review. Ann Nutr Metab 66:242–255

Wakimoto P, Block G (2001) Dietary intake, dietary patterns, and changes with age: an epidemiological perspective. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 56(2):65–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/56.suppl_2.65

King DE, Mainous AG, Lambourne CA (2012) Trends in dietary fiber intake in the United States, 1999–2008. J Acad Nutr Diet 112:642–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2012.01.019

Tuttolomondo A, Simonetta I, Daidone M, Mogavero A, Ortello A, Pinto A (2019) Metabolic and vascular effect of the Mediterranean diet. Int J Mol Sci 20(19):4716. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20194716

Javier Basterra-Gortari F, Ruiz-Canela M, Martínez-González MA et al (2019) Effects of a Mediterranean eating plan on the need for glucose-lowering medications in participants with type 2 diabetes: a subgroup analysis of the PREDIMED trial. Diabetes Care 42:1390–1397. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc18-2475

Rubin R (2020) Fish-rich Mediterranean diet associated with higher cognition. JAMA 323:1998. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.7061

Valls-Pedret C, Sala-Vila A, Serra-Mir M et al (2015) Mediterranean diet and age-related cognitive decline: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 175:1094–1103. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1668

Toledo E, Salas-Salvado J, Donat-Vargas C et al (2015) Mediterranean diet and invasive breast cancer risk among women at high cardiovascular risk in the predimed trial: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 175:1752–1760. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4838

Tomata Y, Larsson SC, Hägg S (2019) Polyunsaturated fatty acids and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a Mendelian randomization study. Eur J Nutr 59:1763–1766. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-019-02126-x

Engelheart S, Akner G (2015) Dietary intake of energy, nutrients and water in elderly people living at home or in nursing home. J Nutr Health Aging 19:265–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-015-0440-0

Berner LA, Becker G, Wise M, Doi J (2013) Characterization of dietary protein among older adults in the United States: amount, animal sources, and meal patterns. J Acad Nutr Diet 113:809–815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2013.01.014

Boirie Y, Morio B, Caumon E, Cano NJ (2014) Nutrition and protein energy homeostasis in elderly. Mech Ageing Dev 136–137:76–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2014.01.008

Lozano-Montoya I, Correa-Pérez A, Abraha I et al (2017) Nonpharmacological interventions to treat physical frailty and sarcopenia in older patients: a systematic overview—the SENATOR project ONTOP series. Clin Interv Aging 12:721–740

Davis CR, Hodgson JM, Woodman R et al (2017) A Mediterranean diet lowers blood pressure and improves endothelial function: results from the MedLey randomized intervention trial. Am J Clin Nutr 105:1305–1313. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.116.146803

Zou P, Dennis CL, Lee R, Parry M (2017) Dietary approach to stop hypertension with sodium reduction for Chinese Canadians (Dashna-CC): a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Nutr Heal Aging 21:1225–1232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-016-0861-4

Zou P (2019) Facilitators and barriers to healthy eating in aged Chinese Canadians with hypertension: a qualitative exploration. Nutrients. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11010111

Seangpraw K, Auttama N, Tonchoy P, Panta P (2019) The effect of the behavior modification program Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) on reducing the risk of hypertension among elderly patients in the rural community of Phayao, Thailand. J Multidiscip Healthc 12:109–118. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S185569

Van Doorn-Van Atten MN, Haveman-Nies A, Van Bakel MM et al (2018) Effects of a multi-component nutritional telemonitoring intervention on nutritional status, diet quality, physical functioning and quality of life of community-dwelling older adults. Br J Nutr 119:1185–1194. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114518000843

Berendsen AAM, van de Rest O, Feskens EJM et al (2018) Changes in dietary intake and adherence to the NU-AGE diet following a one-year dietary intervention among European older adults—results of the NU-AGE randomized trial. Nutrients. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10121905

Schröder H, Cárdenas-Fuentes G, Martínez-González MA et al (2018) Effectiveness of the physical activity intervention program in the PREDIMED-Plus study: a randomized controlled trial 11 Medical and Health Sciences 1117 Public Health and Health Services. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0741-x

Chase JAD, Phillips LJ, Brown M (2017) Physical activity intervention effects on physical function among community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Aging Phys Act 25:149–170

Alrushud AS, Rushton AB, Kanavaki AM, Greig CA (2017) Effect of physical activity and dietary restriction interventions on weight loss and the musculoskeletal function of overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and mixed method data synthesis. BMJ Open 7:e014537. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJOPEN-2016-014537

Correa-Pérez A, Abraha I, Cherubini A et al (2019) Efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions to treat malnutrition in older persons: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The SENATOR project ONTOP series and MaNuEL knowledge hub project. Ageing Res Rev 49:27–48

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Fundación Patrimonio Comunal Olivarero, the California Walnut Commission (Sacramento, CA), and Borges SA and Morella Nuts SA, both in Reus, Spain, for generously donating the olive oil, walnuts, almonds, and hazelnuts used in the study.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. CIBEROBN is an initiative of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain. This work was been partially supported by Grant PI13/02184 from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, and the Sociedad Española de Medicina Interna (SEMI), Spain (Grant DN40585).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RC, MRC, ES were responsible for study conception and design, RC and MRC for laboratory and clinical data, RC, ER, RE, and ES for analysis and interpretation of the data, RC, MRC, ER, and ES for drafting the article, and all authors for critical revision and final approval. RC, ER, RE, and ES wrote the paper, and RE had primary responsibility for the final content. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr Estruch reports personal fees and non-financial support from The Research Foundation on Wine and Nutrition (FIVIN), non-financial support from The Beer and Health Foundation and the European Foundation for Alcohol Research (ERAB), personal fees from Cerveceros de España, personal fees from Sanofi-Aventis, grants from Novartis, outside the submitted work. Dr Ros reports grants, personal fees, non-financial support and other from California Walnut Commission, grants, personal fees, non-financial support and other from Alexion, personal fees, non-financial support and other from Ferrer International, personal fees, non-financial support and other from Danone, outside the submitted work. Dr Lamuela-Raventós reports personal fees and non-financial support from The Beer and Health Foundation and the European Foundation for Alcohol Research (ERAB), personal fees from Cerveceros de España, outside the submitted work. Dr Salas-Salavadó reports non-financial support from the Diabetes and Nutrition Study Group (DNSG) of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and the Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee of the European Association for the study of Diabetes (EASD) during the conduct of the study, grants from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, European Commission, and US National Institutes of Health, other from the Almond Board of California and Patrimonio Comunal Olivarero, personal fees from Danone and the Instituto Danone Spain, and grants and non-financial support from the International Nut and Dried Fruit Council outside the submitted work, and Jordi Salas-Salvadó served on the Scientific Committee of the Spanish Food and Safety Agency and the Spanish Federation of the Scientific Societies of Food, Nutrition, and Dietetics. He is a member of the International Carbohydrate Quality Consortium (ICQC). No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article is reported.

Institutional review board statement

The protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the participating centres. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and is registered at controlled-trials.com as ISRCTN35739639.

Informed consent statement

All participants provided the written informed consent.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset analyzed during the current study is not publicly available due to national data regulations and for ethical reasons, e.g. we do not have the explicit written consent of the study volunteers to make their deidentified data available at the end of the study. However, data described in the manuscript, codebook, and analytic codes will be made available upon request by contacting the PREDIMED Steering Committee (predimed-steering-committe@googlegroups.com). The request will be passed to all the members of the committee for deliberation.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Casas, R., Ribó-Coll, M., Ros, E. et al. Change to a healthy diet in people over 70 years old: the PREDIMED experience. Eur J Nutr 61, 1429–1444 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-021-02741-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-021-02741-7