Abstract

Background

Dietary intake has changed considerably in South European countries, but whether those changes were similar between countries is currently unknown.

Aim of the study

To assess the trends in food availability in Portugal and four other Mediterranean countries from 1966 to 2003.

Methods

Food and Agricultural Organization food balance sheets from Portugal, France, Italy, Greece and Spain. Trends were assessed by linear regression.

Results

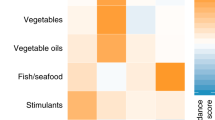

The per capita availability of calories has increased in Portugal, France, Greece, Italy and Spain in the past 40 years. Portugal presented the most rapid growth with an annual increase of 28.5 ± 2.2 kcal (slope ± standard error), or +1000 kcal overall. In animal products, Portugal had an annual increase of 20.7 ± 0.9 kcal, much higher than the other four countries. Conversely, the availabilities of vegetable and fruit only showed a slight growth of 1.0 ± 0.1 kcal/year and 2.5 ± 0.4 kcal/year, respectively, thus increasing the ration of animal to vegetable products. Olive oil availability increased in all countries with the notable exception of Portugal, where a significant decrease was noted. Wine supply decreased in all five countries; in contrast, beer supply started to take up more alcohol share. Percentage of total calories from fat increased from nearly 25% to almost 35% in Portugal during the study period, mainly at the expenses of calories from carbohydrates, whereas the share of protein showed just a slight increase. Furthermore, fat and protein were increasingly provided by animal products.

Conclusions

Portugal is gradually moving away from the traditional Mediterranean diet to a more Westernized diet as well as France, Greece, Italy and Spain. Noticeably, the trends of diet transition were observed relatively faster in Portugal than in the other four Mediterranean countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

http://www.faostat.fao.org/site/379/default.aspx assessed 21st August 2007

http://www.mongabay.com/reference/country_studies/portugal/GOVERNMENT.html, assessed March 19, 2007

References

Alexandratos N (2006) The Mediterranean diet in a world context. Public Health Nutr 9:111–117

Alto Comissariado da Saúde (2005) Implementação do Plano Nacional de Saúde. Um roteiro estratégico para a fase II - 2004/2006 [English version]. In:Ministério da Saúde, p 20

Barr SI (2003) Increased dairy product or calcium intake: is body weight or composition affected in humans? J Nutr 133:245S–248S

Bertakis KD, Azari R (2005) Obesity and the use of health care services. Obes Res 13:372–379

Cruz JA (2000) Dietary habits and nutritional status in adolescents over Europe–Southern Europe. Eur J Clin Nutr 54(Suppl 1):S29–35

Direcção-Geral da Saúde (2004) Plano Nacional de Saúde 2004/2010 - prioridades. In:Ministério da Saúde, p 88

Directorate-General of Health (2005) National programme against obesity [English version]. In: Division of genetic chronic and geriatric diseases (ed). Ministério da Saúde, p 26

Ferreira I, Twisk JW, van Mechelen W, Kemper HC, Stehouwer CD (2005) Development of fatness, fitness, and lifestyle from adolescence to the age of 36 years: determinants of the metabolic syndrome in young adults: the Amsterdam growth and health longitudinal study. Arch Intern Med 165:42–48

Food and Agriculture Organization (2006) Food balance sheets. Available at http://www.faostat.fao.org/site/345/default.aspx (assessed October 2006)

Garcia-Closas R, Berenguer A, Gonzalez CA (2006) Changes in food supply in Mediterranean countries from 1961 to 2001. Public Health Nutr 9:53–60

Graça P (1999) Dietary guidelines and food nutrient intakes in Portugal. Br J Nutr 81(Suppl 2):S99–103

Gual A, Colom J (1997) Why has alcohol consumption declined in countries of southern Europe? Addiction (Abingdon, England) 92(Suppl 1):S21–31

Guerra A, Feldl F, Koletzko B (2001) Fatty acid composition of plasma lipids in healthy Portuguese children: is the Mediterranean diet disappearing? Ann Nutr Metab 45:78–81

Haslam D, Sattar N, Lean M (2006) ABC of obesity. Obesity-time to wake up. Br Med J 333:640–642

Haut Comité de la Santé Publique (2000) Pour une politique nutritionnelle de santé publique en France. Editions ENSP, Rennes

Hibell B, Andersson B, Bjarnason T, Ahlström S, Balakireva O, Kokkevi A, Morgan M (2004) The ESPAD Report: alcohol and other drug use among students in 35 European countries. The Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs, co-operation Group to Combat Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking in Drugs (Pompidou Group) Council of Europe, Stockholm, Sweden

Johnell O, Gullberg B, Kanis JA, Allander E, Elffors L, Dequeker J, Dilsen G, Gennari C, Lopes Vaz A, Lyritis G, et al. (1995) Risk factors for hip fracture in European women: the MEDOS Study. Mediterranean Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Miner Res 10:1802–1815

Kanis J, Johnell O, Gullberg B, Allander E, Elffors L, Ranstam J, Dequeker J, Dilsen G, Gennari C, Vaz AL, Lyritis G, Mazzuoli G, Miravet L, Passeri M, Perez Cano R, Rapado A, Ribot C (1999) Risk factors for hip fracture in men from southern Europe: the MEDOS study. Mediterranean Osteoporosis Study. Osteoporos Int 9:45–54

Kris-Etherton P, Daniels SR, Eckel RH, Engler M, Howard BV, Krauss RM, Lichtenstein AH, Sacks F, St Jeor S, Stampfer M, Grundy SM, Appel LJ, Byers T, Campos H, Cooney G, Denke MA, Kennedy E, Marckmann P, Pearson TA, Riccardi G, Rudel LL, Rudrum M, Stein DT, Tracy RP, Ursin V, Vogel RA, Zock PL, Bazzarre TL, Clark J (2001) Summary of the scientific conference on dietary fatty acids and cardiovascular health: conference summary from the nutrition committee of the American Heart Association. Circulation 103:1034–1039

Kushi L, Giovannucci E (2002) Dietary fat and cancer. Am J Med 113(Suppl 9B):63S–70S

Marques-Vidal P, Dias CM (2005) Trends and determinants of alcohol consumption in Portugal: results from the national health surveys 1995 to 1996 and 1998 to 1999. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 29:89–97

Marques-Vidal P, Dias CM (2005) Trends in overweight and obesity in Portugal: the national health surveys 1995–6 and 1998–9. Obes Res 13:1141–1145

Marques-Vidal P, Goncalves A, Dias CM (2006) Milk intake is inversely related to obesity in men and in young women: data from the Portuguese Health Interview Survey 1998–1999. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 30:88–93

Marques-Vidal P, Ravasco P, Dias CM, Camilo E (2006) Trends of food intake in Portugal, 1987–1999: results from the national health surveys. Eur J Clin Nutr 60:1414–1422

Martins I, Dantas A, Guiomar S, Amorim Cruz JA (2002) Vitamin and mineral intakes in elderly. J Nutr Health Aging 6:63–65

Ministero della Salute (2005) Piano Sanitario Nazionale 2006–2008. Italy, p 100

Naska A, Fouskakis D, Oikonomou E, Almeida MD, Berg MA, Gedrich K, Moreiras O, Nelson M, Trygg K, Turrini A, Remaut AM, Volatier JL, Trichopoulou A (2006) Dietary patterns and their socio-demographic determinants in 10 European countries: data from the DAFNE databank. Eur J Clin Nutr 60:181–190

Neira M, de Onis M (2006) The Spanish strategy for nutrition, physical activity and the prevention of obesity. Br J Nutr 96(Suppl 1):S8–S11

Padez C (2006) Trends in overweight and obesity in Portuguese conscripts from 1986 to 2000 in relation to place of residence and educational level. Public Health 120:946–952

Padez C, Mourao I, Moreira P, Rosado V (2005) Prevalence and risk factors for overweight and obesity in Portuguese children. Acta Paediatr 94:1550–1557

Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Arvaniti F, Stefanadis C (2006) Adherence to the Mediterranean food pattern predicts the prevalence of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes and obesity, among healthy adults; the accuracy of the MedDietScore Prev Med Epub ahead of print

Pyörälä E (1990) Trends in alcohol consumption in Spain, Portugal, France and Italy from the 1950s until the 1980s. Br J Addict 85:469–477

Rodrigues SS, de Almeida MD (2001) Portuguese household food availability in 1990 and 1995. Public Health Nutr 4:1167–1171

Schmidhuber J, Traill WB (2006) The changing structure of diets in the European Union in relation to healthy eating guidelines. Public Health Nutr 9:584–595

Schröder H, Marrugat J, Vila J, Covas MI, Elosua R (2004) Adherence to the traditional mediterranean diet is inversely associated with body mass index and obesity in a spanish population. J Nutr 134:3355–3361

Silm S, Ahas R (2005) Seasonality of alcohol-related phenomena in Estonia. Int J Biometeorol 49:215–223

Simpura J, Paakkanen P, Mustonen H (1995) New beverages, new drinking contexts? Signs of modernization in Finnish drinking habits from 1984 to 1992, compared with trends in the European Community. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 90:673–683

Snyder LB, Milici FF, Mitchell EW, Proctor DC (2000) Media, product differences and seasonality in alcohol advertising in 1997. J Stud Alcohol 61:896–906

Trichopoulos D, Lagiou P (2004) Mediterranean diet and overall mortality differences in the European Union. Public Health Nutr 7:949–951

Trichopoulou A, Lagiou P (1997) Healthy traditional mediterranean diet: an expression of culture, history, and lifestyle. Nutr Rev 55:383–389

Tur JA, Romaguera D, Pons A (2004) Food consumption patterns in a mediterranean region: does the mediterranean diet still exist? Ann Nutr Metab 48:193–201

Unidade de Comunicação e Imagem (2006) Balança alimentar portuguesa 1990–2003. In:Instituto Nacional de Estatística, Lisboa, Portugal, p 6

van der Wilk EA, Jansen J (2005) Lifestyle-related risks: are trends in Europe converging? Public Health 119:55–66

Weaver CM, Boushey CJ (2003) Milk-good for bones, good for reducing childhood obesity? J Am Diet Assoc 103:1598–1599

WHO (2003) Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. Report of a joint WHO/FAO expert consultation. In: WHO (ed) Technical report series no. 916. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, p 160

WHO (2006) Obesity and overweight. Fact sheet no. 311. In: World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

WHO (1999) Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic; report of a WHO consultation. In: WHO (ed) Technical report series no. 894. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, p 268

Willett WC, Sacks F, Trichopoulou A, Drescher G, Ferro-Luzzi A, Helsing E, Trichopoulos D (1995) Mediterranean diet pyramid: a cultural model for healthy eating. Am J Clin Nutr 61:1402S–1406S

Yngve A, Wolf A, Poortvliet E, Elmadfa I, Brug J, Ehrenblad B, Franchini B, Haraldsdottir J, Krolner R, Maes L, Perez-Rodrigo C, Sjostrom M, Thorsdottir I, Klepp KI (2005) Fruit and vegetable intake in a sample of 11-year-old children in 9 European countries: The Pro Children Cross-sectional Survey. Ann Nutr Metab 49:236–245

Acknowledgements

The Centro de Nutrição e Metabolismo of the Instituto de Medicina Molecular is partially funded by a grant from the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia ref. RUN 437. Conflict of interest: none.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Annex

Annex

Assessing the effect of several foodstuffs on the trends in caloric/nutrient availability

Briefly, let the timely change in total caloric availability be modeled by a simple linear regression:

Where at is the total caloric availability at time 0 and βt is the slope (increase/decrease) for the change in total caloric availability, for example an increase in 50 kcal/year. The time changes for animal and vegetable-derived caloric availabilities can be calculated similarly:

Supposing alcohol-derived caloric availability is negligible or included in vegetable caloric availability, one can postulate that:

Introducing (1), (2) and (3) into (4) leads to the equation

At time = 0, equation (5) simplifies into

indicating that the total caloric availability at time zero (and actually at any time) should be equal to the sum of animal and vegetable caloric availability, as stated in equation (4). Using (6) and (5) we obtain for any time

Which indicates that the changes in total caloric availability can be expressed as the sum of the changes in animal and vegetable caloric availabilities. Thus, the percentage of change in total caloric availability explained by changes in vegetable-derived calories can be easily calculated as

For example, for an increase in total caloric availability of 50 kcal/year and a corresponding increase of 30 kcal/year in vegetable caloric availability, then the percentage of total caloric availability change explained by changes in vegetable-derived caloric availability is

Which indicates that most of the increase in total caloric availability is due to vegetable products. Actually, equation (8) is not limited to positive (increasing) trends as, using another example, the previous increase of 50 kcal/year in total caloric availability could also be obtained by an increase of 80 kcal/year in vegetable and a decrease of 30 kcal/year in animal availability. Thus, a similar change in total caloric/nutrient availability can be obtained by completely different trends as regards the foodstuffs analyzed.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Q., Marques-Vidal, P. Trends in food availability in Portugal in 1966–2003. Eur J Nutr 46, 418–427 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-007-0681-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-007-0681-8