Summary

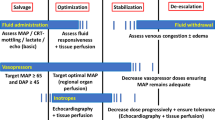

Rational hemodynamic therapy in septic patients should include the following strategies: Adequate fluid resuscitation therapy is one of the most important steps. Crystaloid or colloid solutions are considered to be equally beneficial. The underlying principle is optimization of the myocardial preload. The concept of DO2 maximization, by means of high-dose catecholamine administration, is to be dismissed. Dobutamine is the catecholamine of choice for decreased cardiac pump function treatment. In determining whether a further DO2 increase is indicated, one must follow the markers of peripheral perfusion and organ function (i. e. diuresis, lactate plasma concentration, central venous O2 saturation). Inadequate perfusion pressure should not be tolerated, just because of fear from the potentially unfavorable effects of the vasopressor agents. Perfusion pressure should also be controlled, paying close attention to the indices of peripheral perfusion and organ function. Both dopamine and noradrenaline are recommended as vasopressor agents. However, due to the potentially unfavorable effects of dopamine, noradrenaline appears to be the more suitable choice. Vasopressin should be administered, if ever, only in situations, in which adequate blood pressure cannot be achieved with the better established vasopressors, since vasopressin-induced negative effects on the microcirculation cannot be ruled out. Currently, there is no sufficiently proven therapeutic strategy, enabling a targetted improvement of the regional blood flow, other than through stabilization of the global hemodynamics. The concept of low-dose dopamine administration should be clearly dismissed from modern practice. Regarding dopexamine, there are also no data available to, justify its clinical use.

Zusammenfassung

Eine rationale Kreislauftherapie bei septischen Patienten sollte folgende Strategien beinhalten: Eine adäquate Volumentherapie ist eine der wichtigsten Maßnahmen. Kristalloide oder kolloidale Substanzen werden als gleichwertig empfohlen. Grundlegendes Prinzip ist die Optimierung der myokardialen Vorlast. Das Konzept der Maximierung des DO2 mittels hochdosierter Katecholamine ist abzulehnen. Zur Therapie der eingeschränkten Pumpfunktion ist Dobutamin Katecholamin der Wahl. Zur Entscheidung, ob ein weiterer DO2-Anstieg sinnvoll ist, müssen die Marker der peripheren Perfusion und Organfunktion (z. B. Diurese, Laktat, zentralvenöse O2-Sättigung) beachtet werden. Ein inadäquater Perfusionsdrucks sollte nicht wegen potentieller ungünstiger Effekte von Vasopressoren toleriert werden. Auch der Perfusionsdruck muss unter Beachtung von Parametern der peripheren Perfusion und Organfunktion titriert werden. Sowohl Dopamin als auch Noradrenalin werden als Vasopressoren empfohlen. Aufgrund potentiell ungünstiger Effekte von Dopamin scheint Noradrenalin aber besser geeignet. Vasopressin sollte, wenn überhaupt, nur in Situationen eingesetzt werden, in denen ein adäquater Blutdruck mittels etablierter Vasopressoren nicht zu erzielen ist, denn für Vasopressin sind negative Effekte auf die Mikrozirkulation nicht auszuschließen. Es gibt z. Z. keine hinreichend gesicherte Therapieoption, die über die Stabilisierung der globalen Hämodynamik hinaus, eine gezielte Beeinflussung der regionalen Zirkulation ermöglicht. Das Konzept einer niedrig-dosierten Dopamingabe (Low-dose Dopamin, Dopamin in Nierendosis) muss heute eindeutig abgelehnt werden. Auch für Dopexamin liegen z. Z. keine Daten vor, die den klinischen Einsatz rechtfertigen.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Alderson P, Bunn F, Lefebvre C et al (2003) Human albumin solution for resuscitation and volume expansion in critically ill patients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3

Allman KG, Stoddart AP, Kennedy MM et al (1996) L-arginine augments nitric oxide production and mesenteric blood flow in ovine endotoxemia. Am J Physiol 271:H1296–1301

Annane D, Sebille V, Charpentier C et al (2002) Effect of treatment with low doses of hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone on mortality in patients with septic shock. JAMA 288:862–871

Aruoma OI, Halliwell B, Hoey BM et al (1989) The antioxidant action of N-acetylcysteine: its reaction with hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical, superoxide, and hypochlorous acid. Free Radic Biol Med 6:593–597

Bellomo R, Chapman M, Finfer S et al (2000) Low-dose dopamine in patients with early renal dysfunction: a placebo-controlled randomised trial. Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society (ANZICS) Clinical Trials Group. Lancet 356:2139–2143

Bollaert PE, Bauer P, Audibert G et al (1990) Effects of epinephrine on hemodynamics and oxygen metabolism in dopamine-resistant septic shock. Chest 98:949–953

Bollaert PE, Charpentier C, Levy B et al (1998) Reversal of late septic shock with supraphysiologic doses of hydrocortisone. Crit Care Med 26:645–650

Bone RC, Fisher CJ Jr, Clemmer TP et al (1987) A controlled clinical trial of high-dose methylprednisolone in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 317:653–658

Briegel J, Forst H, Haller M et al (1999) Stress doses of hydrocortisone reverse hyperdynamic septic shock: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, single-center study. Crit Care Med 27:723–732

Brown G, Frankl D, Phang T (1996) Continuous infusion of methylene blue for septic shock. Postgrad Med J 72:612–614

Burchardi H, Briegel J, Eckart J et al (2000) Expertenforum: Hämodynamisch aktive Substanzen in der Intensivmedizin. Anästhesiologie & Intensivmedizin 562–631

Choi PT, Yip G, Quinonez LG et al (1999) Crystalloids vs colloids in fluid resuscitation: a systematic review. Crit Care Med 27:200–210

Cook D, Guyatt G (2001) Colloid use for fluid resuscitation: evidence and spin. Ann Intern Med 135:205–208

De Backer D, Creteur J, Silva E et al (2003) Effects of dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine on the splanchnic circulation in septic shock: which is best? Crit Care Med 31:1659–1667

Dellinger RP, Carlet JM, Masur H et al (2004) Surviving sepsis campaign guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Intensive Care Med 30:536–555

Di Giantomasso D, Morimatsu H, May CN et al (2003) Intrarenal blood flow distribution in hyperdynamic septic shock: effect of norepinephrine. Crit Care Med 31:2509–2513

Dive A, Foret F, Jamart J et al (2000) Effect of dopamine on gastrointestinal motility during critical illness. Intensive Care Med 26:901–907

Duke GJ, Briedis JH, Weaver RA (1994) Renal support in critically ill patients: low-dose dopamine or lowdose dobutamine? Crit Care Med 22:1919–1925

Dunser MW, Mayr AJ, Ulmer H et al (2001) The effects of vasopressin on systemic hemodynamics in catecholamine-resistant septic and postcardiotomy shock: a retrospective analysis. Anesth Analg 93:7–13

Giraud GD, MacCannell KL (1984) Decreased nutrient blood flow during dopamine- and epinephrine-induced intestinal vasodilation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 230:214–220

Gutierrez G, Clark C, Brown SD et al (1994) Effect of dobutamine on oxygen consumption and gastric mucosal pH in septic patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 150:324–329

Hannemann L, Korell R, Meier-Hellmann A et al (1993) Hypertone Losungen auf der Intensivstation. Zentralbl. Chir 118:245–249

Harrison PM, Wendon JA, Gimson AE et al (1991) Improvement by acetylcysteine of hemodynamics and oxygen transport in fulminant hepatic failure. N Engl J Med 324:1852–1857

Hebert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA et al (1999) A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med 340:409–417

Heyland DK, Cook DJ, King D et al (1996) Maximizing oxygen delivery in critically ill patients: a methodologic appraisal of the evidence. Crit Care Med 24:517–524

Hill GE, Frawley WH, Griffith KE et al (2003) Allogeneic blood transfusion increases the risk of postoperative bacterial infection: a meta-analysis. J Trauma 54:908–914

Hollenberg SM, Ahrens TS, Astiz ME et al (1999) Practice parameters for hemodynamic support of sepsis in adult patients in sepsis. Crit Care Med 27:639–660

Holmes CL, Walley KR, Chittock DR et al (2001) The effects of vasopressin on hemodynamics and renal function in severe septic shock: a case series. Intensive Care Med 27:1416–1421

Kern H, Schroder T, Kaulfuss M et al (2001) Enoximone in contrast to dobutamine improves hepatosplanchnic function in fluid-optimized septic shock patients. Crit Care Med 29:1519–1525

Kiefer P, Tugtekin I, Wiedeck H et al (2000) Effect of a dopexamine-induced increase in cardiac index on splanchnic hemodynamics in septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 161:775–779

Klinzing S, Simon M, Reinhart K et al (2003) High-dose vasopressin is not superior to norepinephrine in septic shock. Crit Care Med 31:2646–2650

Kreimeier U, Frey L, Dentz J et al (1991) Hypertonic saline dextran resuscitation during the initial phase of acute endotoxemia: effect on regional blood flow. Crit Care Med 19:801–809

Kreimeier U, Messmer K (1991) Zum Einsatz hypertoner Kochsalzlosungen in der Intensiv- und Notfallmedizin—Entwicklungen und Perspektiven. Klin Wochenschr 69(Suppl 26):134–142

Landry DW, Levin HR, Gallant EM et al (1997) Vasopressin deficiency contributes to the vasodilation of septic shock. Circulation 95:1122–1125

Leier CV (1988) Regional blood flow responses to vasodilators and inotropes in congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol 62:86E–93E

Levy B, Bollaert PE, Charpentier C et al (1997) Comparison of norepinephrine and dobutamine to epinephrine for hemodynamics, lactate metabolism, and gastric tonometric variables in septic shock: a prospective, randomized study. Intensive Care Med 23:282–287

Levy B, Bollaert PE, Lucchelli JP et al (1997) Dobutamine improves the adequacy of gastric mucosal perfusion in epinephrine-treated septic shock. Crit Care Med 25:1649–1654

Marik PE, Sibbald WJ (1993) Effect of stored-blood transfusion on oxygen delivery in patients with sepsis. JAMA 269:3024–3029

Martikainen TJ, Tenhunen JJ, Uusaro A et al (2003) The effects of vasopressin on systemic and splanchnic hemodynamics and metabolism in endotoxin shock. Anesth Analg 97:1756–1763

Martin C, Viviand X, Leone M et al (2000) Effect of norepinephrine on the outcome of septic shock. Crit Care Med 28:2758–2765

Meier-Hellmann A, Bredle DL, Specht M et al (1999) Dopexamine increases splanchnic blood flow but decreases gastric mucosal pH in severe septic patients treated with dobutamine. Crit Care Med 27:2166–2171

Meier-Hellmann A, Reinhart K, Bredle DL et al (1997) Epinephrine impairs splanchnic perfusion in septic shock. Crit Care Med 25:399–404

Müller-Werdan U, Prondzinsky R, Witthaut R et al (1997) The heart in sepsis and MODS. Wien Klin Wochenschr 109:3–24

Neviere R, Mathieu D, Chagnon JL et al (1996) The contrasting effects of dobutamine and dopamine on gastric mucosal perfusion in septic patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 154:1684–1688

O’Brien A, Clapp L, Singer M (2002) Terlipressin for norepinephrine-resistant septic shock. Lancet 359:1209–1210

Patel BM, Chittock DR, Russell JA et al (2002) Beneficial effects of short-term vasopressin infusion during severe septic shock. Anesthesiology 96:576–582

Petros A, Bennett D, Vallance P (1991) Effect of nitric oxide synthase inhibitors on hypotension in patients with septic shock. Lancet 338:1557–1558

Rank N, Michel C, Haertel C et al (2000) N-acetylcysteine increases liver blood flow and improves liver function in septic shock patients: results of a prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Crit Care Med 28:3799–3807

Reinelt H, Radermacher P, Fischer G et al (1997) Effects of a dobutamine-induced increase in splanchnic blood flow on hepatic metabolic activity in patients with septic shock. Anesthesiology 86:818–824

Reinhart K, Spies CD, Meier-Hellmann A et al (1995) N-acetylcysteine preserves oxygen consumption and gastric mucosal pH during hyperoxic ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 151:773–779

Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S et al (2001) Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 345:1368–1377

Rubanyi GM, Vanhoutte PM (1986) Superoxide anions and hyperoxia inactivate endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Am J Physiol 250:H822–827

Sakka SG, Bredle DL, Reinhart K et al (1999) Comparison between intrathoracic blood volume and cardiac filling pressures in the early phase of hemodynamic instability of patients with sepsis or septic shock. J Crit Care 14:78–83

Scheeren T, Radermacher P (1997) Prostacyclin (PGI2): new aspects of an old substance in the treatment of critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med 23:146–158

Schierhout G, Roberts I (1998) Fluid resuscitation with colloid or crystalloid solutions in critically ill patients: a systematic review of randomised trials. BMJ 316:961–964

Schneider F, Lutun P, Hasselmann M et al (1992) Methylene blue increases systemic vascular resistance in human septic shock. Preliminary observations. Intensive Care Med 18:309–311

Silverman HJ, Tuma P (1992) Gastric tonometry in patients with sepsis. Effects of dobutamine infusions and packed red blood cell transfusions. Chest 102:184–188

Spies CD, Reinhart K, Witt I et al (1994) Influence of N-acetylcysteine on indirect indicators of tissue oxygenation in septic shock patients: results from a prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Crit Care Med 22:1738–1746

Sprung CL, Bernard GR, Dellinger RP (2001) Guidelines for the management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Intensive Care Med 27:1–134

The Veterans Administration Systemic Sepsis Cooperative Study Group (1987) Effect of high-dose glucocorticoid therapy on mortality in patients with clinical signs of systemic sepsis. N Engl J Med 317:659–665

Tsuneyoshi I, Yamada H, Kakihana Y et al (2001) Hemodynamic and metabolic effects of low-dose vasopressin infusions in vasodilatory septic shock. Crit Care Med 29:487–493

Uusaro A, Ruokonen E, Takala J (1995) Gastric mucosal pH does not reflect changes in splanchnic blood flow after cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth 74:149–154

Vamvakas EC (2004) White blood cell-containing allogeneic blood transfusion, postoperative infection and mortality: a meta-analysis of observational ‘before-and-after’ studies. Vox Sang 86:111–119

Van den Berghe G, de Zegher F (1996) Anterior pituitary function during critical illness and dopamine treatment. Crit Care Med 24:1580–1590

van Haren FM, Rozendaal FW, van der Hoeven JG (2003) The effect of vasopressin on gastric perfusion in catecholamine-dependent patients in septic shock. Chest 124:2256–2260

Varga C, Pavo I, Lamarque D et al (1998) Endogenous vasopressin increases acute endotoxin shock-provoked gastrointestinal mucosal injury in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol 352:257–261

Vincent JL, Van der Linden P, Domb M et al (1987) Dopamine compared with dobutamine in experimental septic shock: relevance to fluid administration. Anesth Analg 66:565–571

Wright CE, Rees DD, Moncada S (1992) Protective and pathological roles of nitric oxide in endotoxin shock. Cardiovasc Res 26:48–57

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Serie: Die Intensivtherapie bei Sepsis und Multiorganversagen Herausgegeben von L. Engelmann (Leipzig)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Meier-Hellmann, A. Therapie des Kreislaufversagens bei Sepsis. Intensivmed 41, 583–591 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00390-004-0514-4

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00390-004-0514-4