Abstract

Land–sea surface air temperature (SAT) contrast, an index of tropospheric thermodynamic structure and dynamical circulation, has shown a significant increase in recent decades over East Asia during the boreal summer. In Part I of this two-part paper, observational data and the results of transient warming experiments conducted using coupled atmosphere–ocean general circulation models (GCMs) are analyzed to examine changes in land–sea thermal contrast and the associated atmospheric circulation over East Asia from the past to the future. The interannual variability of the land–sea SAT contrast over the Far East for 1950–2012 was found to be tightly coupled with a characteristic tripolar pattern of tropospheric circulation over East Asia, which manifests as anticyclonic anomalies over the Okhotsk Sea and around the Philippines, and a cyclonic anomaly over Japan during a positive phase, and vice versa. In response to CO2 increase, the cold northeasterly winds off the east coast of northern Japan and the East Asian rainband were strengthened with the circulation pattern well projected on the observed interannual variability. These results are commonly found in GCMs regardless of future forcing scenarios, indicating the robustness of the East Asian climate response to global warming. The physical mechanisms responsible for the increase of the land–sea contrast are examined in Part II.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The summertime climate over East Asia, located between the Eurasian continent and the western North Pacific, is characterized by two anticyclonic circulations: one over the Pacific Ocean and the other over East Siberia with an extratropical rainband in between. These two anticyclones exhibit great control over interannual variabilities of the large-scale climate over East Asia (e.g. Ninomiya and Murakami 1987). The one located in the western Pacific, i.e. the subtropical high, is an essential component of the East Asian summer monsoon system including the warm moist southwesterly winds from the tropics (e.g. Seo et al. 2012; Imada et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2013). Previous studies have investigated the influence of convective activity over the tropical western Pacific, around and to the east of the Philippines, on the East Asian climate through a teleconnection pattern called Pacific-Japan (PJ) pattern (e.g. Nitta 1987) and its relationship with tropical interannual variability (e.g. Kawamura et al. 1998; Wang et al. 2001; Kosaka et al. 2011). The present study focuses on the influence from the north on the East Asian climate, namely the intensity of the anticyclone over East Siberia and the Okhotsk Sea (e.g. Suda and Asakura 1955; Wang 1992; Hirota and Takahashi 2012; Park and Ahn 2014). The East Siberian blocking high and the Okhotsk high at the surface are known to be coupled tightly (Nakamura and Fukamachi 2004; Tachibana et al. 2004; Wakabayashi and Kawamura 2004; Arai and Kimoto 2005; Sato and Takahashi 2007). The anomalous high over the Okhotsk Sea is associated with an anomalously cold summer in northeastern Japan caused by a cold northeasterly wind called Yamase, which has a significant influence on rice crops (e.g. Ninomiya and Mizuno 1985; Kodama 1997; Endo 2012; Kanno et al. 2013). The Okhotsk high also has great impact on the location of the Meiyu-Baiu front (e.g. Kurashima 1969; Wang 1992). Several studies have shown that anomalous surface warming over the Far East, including East Siberia and East Asia, relative to the ocean, intensifies the anticyclone over East Siberia and the Okhotsk Sea on an interannual timescale (Nakamura and Fukamachi 2004; Tachibana et al. 2004; Arai and Kimoto 2005). The land–sea thermal contrast over the Far East is an essential factor in the observed interannual variabilities of the East Asian climate through the variations of atmospheric circulation patterns (e.g. Li and Yanai 1996; Jin et al. 2013).

The changes of surface air temperature (SAT) and the intensity of the anticyclone over the Far East might play a key role in future climate change projections over East Asia (e.g. Arai and Kimoto 2008). Recent studies have revealed that the land–sea thermal contrast increases gradually under global warming as a robust feature simulated in general circulation models (GCMs, e.g. Manabe et al. 1991; Lambert and Chiang 2007; Joshi et al. 2008; Dommenget 2009; Boer 2011). Previous studies have documented well the projected future changes in surface pressure patterns and atmospheric circulation in response to changes in the land–sea thermal contrast (Ueda et al. 2006; Sun et al. 2010; Fasullo 2012; Wu et al. 2012; Bayr and Dommenget 2013) and sea surface temperature (SST) patterns in the tropics and subtropics (Inoue and Ueda 2012; Fan et al. 2013). The land–sea thermal contrast over the Asian monsoon region varies under different climate forcings, which induce changes in the strength of the Asian monsoon (e.g. Ueda et al. 2011; Man et al. 2012).

In contrast, the influence of the land–sea thermal contrast in the mid- and high-latitudes of the Far East on future changes in atmospheric circulation has received little attention. The anomalous surface warming over the Far East in the mid- and high-latitudes under global warming could influence the East Asian climate through changes in the atmospheric circulation pattern. Zhu et al. (2012) suggested that the recent changes of the circulation pattern over East Asia might be associated with a surface warming trend over the continental interior of Asia. Kimoto (2005) revealed that continental warming in an atmosphere-only GCM, due solely to an increasing CO2 radiative effect, could generate an anticyclonic circulation over the Far East similar to that simulated in global warming experiments. Arai and Kimoto (2008) demonstrated a significant land–sea SAT contrast and its contribution to the anticyclonic circulation anomaly over East Siberia during boreal summer in ensemble global warming experiments. However, recent changes in the land–sea SAT contrast and circulation patterns over the Far East in observational data have not been compared with the modeled changes and previous studies have not confirmed the consistency of the simulated changes among the different models.

It is not always true that spatial patterns of climate changes due to imposed external forcings are similar to that of natural variability in climate system. However, previous studies revealed that some parts of projected future changes in mean states have similar structures to interannual climate variabilities (e.g. Palmer 1999; Corti et al. 1999; Yamaguchi and Noda 2006; Arai and Kimoto 2008; Kosaka and Nakamura 2011). Yamaguchi and Noda (2006) showed some similarities in spatial patterns of natural variabilities and projected changes under global warming over the Pacific region. Kimoto (2005) and Kosaka and Nakamura (2011) revealed that climatological response in atmospheric circulation under global warming over the summertime western North Pacific resembles to the PJ pattern associated with convective activity over the tropical western Pacific. Over the Far East, the land–sea thermal contrast that is essential for the interannual variability could also be an important factor for the projected future change.

On a global perspective, anomalous surface warming over land relative to the ocean is a robust trend that is confirmed both by observations and by GCM simulations in a warming climate (Sutton et al. 2007; Compo and Sardeshmukh 2009; Jones et al. 2013). In this study, we examine how the land–sea thermal contrast over the Far East explains the change in atmospheric circulation under global warming, and the consistency of the observed trend of the land–sea contrast and simulated changes in recent decades. We also compare the change in atmospheric circulation under the global warming and its interannual variability associated with land–sea thermal contrast over the Far East. In Kamae et al. (2014, hereafter Part II), a companion paper, the physical mechanisms of the changes in regional land–sea thermal contrast and associated atmospheric circulation are examined in detail. Section 2 describes the observational data, models and experiments analyzed in this study. Section 3 presents the observed variations of surface and tropospheric land–sea contrast and the associated circulation patterns during boreal summer over East Asia. In Sect. 4, the historical and future changes modeled by an ensemble of GCMs are examined. Section 5 presents a summary and discussion, and outlines the remaining issues leading to Part II.

2 Data and methods

2.1 Observational and reanalysis data

We used SAT data compiled at the Met Office Hadley Centre and the Climate Research Unit, University of East Anglia, referred to as HadCRUT4 (Morice et al. 2012) to investigate the variability and trends over the land and ocean during 1850–2012. The data used was limited to those years in which enough samples are available (see Sect. 3.1). Three-dimensional atmospheric data were taken from ERA-Interim for 1979–2012 (Dee et al. 2011), the latest global atmospheric reanalysis product from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts. To investigate the precipitation variability over land associated with land–sea contrast over East Asia we used the gauge-based high-quality precipitation dataset, APHRODITE v1101 (Yatagai et al. 2012). We selected the Monsoon Asia version of APHRODITE with a spatial resolution of 0.5° × 0.5°. The APHRODITE data enable the investigation of long-term (1951–2007) and high-resolution spatial variations of precipitation over land. We also compared our results with other precipitation dataset compiled in the Global Precipitation Climatology Project (version 2.2, Adler et al. 2003) for 1979–2011 and confirmed that no significant discrepancy was found in their large-scale variabilities. In this study, we only show the results of the former dataset. All the data were averaged from June to August (JJA) for each year prior to the analysis.

2.2 CMIP5 models and experiments

We use the multi-model dataset archived under the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project phase 5 (CMIP5, Taylor et al. 2012) to quantify past and future changes. Specifically, outputs of the following experiments are analyzed: idealized 1 % per year CO2 increase run (hereafter 1 % CO2), historical run from the late nineteenth century to 2005 (historical), and representative concentration pathway (RCP) run from 2006 to 2100. In 1 % CO2, the atmospheric CO2 concentration was prescribed and increased by 1 % per year, starting from the value for the pre-industrial control simulation (hereafter control run), until quadrupling after 140 years. All other external forcings including aerosols were kept at their pre-industrial values. The models used in this study are 16 GCMs for which all the outputs used are available (Table 1). Note that the models used in Part II paper are 9 out of 16 GCMs (marked * in Table 1). The 16 models cover the wide range of equilibrium climate sensitivity among the CMIP5 models (Andrews et al. 2012). In Part I, we focus mainly on the RCP8.5 and 1 % CO2 runs which have relatively strong radiative forcings (the effective radiative forcing owing to the CO2 quadrupling in the models is about 7.5 W m−2, Kamae and Watanabe 2012). To quantify the scenario-dependency of the results, we used the outputs of the four types of RCP run (RCP2.6, RCP4.5, RCP6.0, and RCP8.5, Meinshausen et al. 2011) conducted in the MIROC5 model (Watanabe et al. 2010) in Sect. 4.3. The four RCP runs have different settings for land use, concentrations of trace gases, and aerosols.

3 Observed changes in land–sea contrast and associated atmospheric circulation

3.1 Surface temperature contrast between land and ocean over the Far East

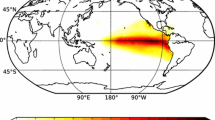

First, we examined the observed trend of SAT over land and the ocean in recent decades. Figure 1 shows the spatial distribution of the JJA-mean SAT linear trend for 1950–2012 based on HadCRUT4 data. We examined this period because the SAT data is less available in the first half of the twentieth century (see Fig. 8 in Jones et al. 2013). In terms of the global mean value, during this period the JJA-mean SAT shows an increasing trend of 0.10 K decade−1. The positive SAT trend over the ocean is seen mainly in the tropics; however, it is weaker than the warming trend over land, indicating a globally increasing trend of the land–sea SAT contrast. The negative trends appear over the Southern Ocean and the North Pacific Ocean. Some parts of regional trends might be influenced by changes of land use, aerosol emissions, and decadal variations in the atmosphere and ocean (e.g. Jones et al. 2013; Kumar et al. 2013). As indicated by earlier studies, the observed patterns of warming/cooling over the Pacific are influenced by a phase of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (Mantua and Hare 2002) over the 1950–2012 period (Yasunaga and Hanawa 2002; Trenberth et al. 2007; Jones et al. 2013). The most parts of the warming over the low-latitude oceans except central and eastern Pacific and some parts of the land warming are statistically significant. Over the mid- and high-latitude, some parts of the Far East and sub-Arctic North America show statistically significant warming trends in this period.

The Far East region (110°E–170°E, 30°N–70°N, black rectangle in Fig. 1) is one of the regions showing a significant increase of land–sea SAT contrast. Figure 2 presents the time series of land- and ocean-mean SAT over the Far East and its difference (land minus ocean). The plot shown is limited to those years in which more than 90 % of the samples are available, but it exhibits clearly that the SAT over land (1949–2010) and ocean (1916–2012) has increasing trends of 0.15 and 0.07 K decade−1, respectively. The SAT trend over land (ocean) during 1949–2010 (1916–2012) is statistically significant (not statistically significant) at the 95 % level. The land SAT shows a remarkable increase in 1980–2010, resulting in a positive trend in the land–sea SAT contrast (0.11 K decade−1, statistically significant at the 95 % level) in 1949–2010. A part of this positive trend is contributed by the cooling trend of SST in the Pacific (Fig. 1), but the increase of SAT over land is the main factor in the increasing land–sea contrast (Fig. 2).

Time series of JJA-mean a land- and b ocean-mean SAT (K) and c land–sea contrast (a − b) averaged over the Far East (110°E–170°E, 30°N–70°N, black rectangle in Fig. 1). All values are anomalies relative to averages in 1949–1978. The years in which data in ≥10 % of areas are not available are not plotted. The lines and labeled values mean linear trends (K decade−1)

3.2 Interannual variabilities associated with SAT contrast over the Far East

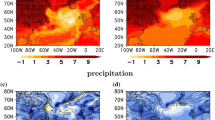

The large interannual variability in the land–sea SAT contrast (Fig. 2c) might be associated with atmospheric thermodynamic and dynamic structures over the Far East. Figure 3 shows the JJA anomalies in the atmospheric circulation obtained from a regression on the interannual variability of the land–sea SAT contrast over the Far East (i.e. the detrended time series of Fig. 2c). The thickness difference between 300 and 850 hPa (Z3085) indicates a tropospheric temperature change (Fig. 3b). The variations of Z3085 over land and ocean correspond well with the land–sea SAT contrast (positive and negative regressions over land and ocean, Fig. 3a). The eddy component of the geopotential height at 500 hPa (Z eddy 500), defined as deviations from the zonal mean (Kimoto 2005), is also correlated with the land–sea SAT contrast, indicating that the SAT contrast over the Far East corresponds well with the contrasts of thickness and geopotential field in the mid-troposphere (not shown). Specifically, the anticyclonic (cyclonic) anomaly in the mid-troposphere over land (ocean) appears when the anomalous SAT contrast is positive. The spatial pattern of sea level pressure (Fig. 3c) shows positive anomalies over the Okhotsk Sea and around the Philippines and a negative anomaly over the western North Pacific to Japan, resembling a tripolar pattern of interannual variability over East Asia during summer (Arai and Kimoto 2008; Hirota and Takahashi 2012). In the positive phase of this pattern, the surface Okhotsk high, the cold northeasterly to northern Japan and precipitation over the Meiyu-Baiu region tend to be intense (Fig. 3d). These results indicate that the land–sea SAT contrast couples tightly with the interannual variability of the East Asian summertime climate.

Spatial patterns of regression coefficients with detrended land–sea SAT contrast (Fig. 2c) over the Far East. a HadCRUT4 SAT (K K−1). Stipples indicate the areas with 95 % statistical confidence. b Thickness between 300 and 850 hPa levels (Z3085, shading, m K−1) and anomaly of geopotential height at 500 hPa from zonal-mean (Z eddy 500, contours, m K−1) in ERA-Interim. c Sea level pressure (shading and contours, hPa K−1) and horizontal wind at 850 hPa (vectors, m s−1 K−1). The wind vectors with wind speed ≤ 0.5 m s−1 K−1 are omitted for clarity. The areas with 95 % statistical confidence in b, c are hatched. d APHRODITE precipitation (version 1101, mm day−1 K−1)

The contrast of tropospheric thermodynamic structure was examined further by a cross section along the line across the anticyclone over land and the cyclone over the ocean (130°E, 65°N to 160°E, 35°N, blue line in Fig. 3b). Figure 4a–c shows the vertical structures of temperature, geopotential height, and circulation over the Far East. Note that the structures shown are not sensitive to the position of the axis line (figures not shown) because of the well-organized large-scale structure (positive in temperature and geopotential height over land and negative over the ocean, Fig. 3b). The vertical section of the temperature anomaly (Fig. 4a) shows a clear land–sea contrast (warm over land and cold over the ocean in the positive phase of the SAT contrast) throughout the troposphere (250–1000 hPa). The geopotential height (Fig. 4b) shows that the barotropic structure of the land–sea contrast, including the lower stratosphere (100–1000 hPa), is associated with the temperature variation (Fig. 4a). The axis-orthogonal wind (U orth ), defined as the speed of the horizontal wind vector perpendicular to the cross section (positive southwesterly), shows a northeasterly anomaly (U orth < 0, Fig. 4c) between the land and sea according to the positive land–sea thermodynamic contrast (Fig. 4a, b). The northeasterly over northern Japan in the lower troposphere (Fig. 3c) is consistent with the negative anomaly of U orth (Fig. 4c).

Vertical structures of regression coefficient of a temperature (K K−1), b geopotential height anomaly from zonal-mean (m K−1) with detrended land–sea SAT contrast (Fig. 2c), and c axis-orthogonal wind (U orth ) on the land-to-ocean line (blue line in Fig. 3a). Contours in c are geopotential height (same as b). The areas with 95 % statistical confidence are stippled. d–f Similar to a–c but for linear trends in 1979–2012. The lines in (b, e) represent Z3085 (right axis, m K−1 and m 34 year−1, respectively)

3.3 Past trends in thermodynamic conditions and dynamical atmospheric circulation

The observed increasing trend in SAT contrast in recent decades (0.11 K decade−1, Fig. 2c) also has some influences on the thermodynamic and dynamic structure of the troposphere. Figure 4d–f shows linear trends of temperature, geopotential height, and U orth for 1979–2012. Note that a linear trend in 34 years corresponds to a change per 0.34 K increase in the land–sea SAT contrast. The tropospheric and stratospheric temperatures show opposite trends (positive and negative, respectively) which are consistent with the classic picture of the temperature response to a doubling of CO2 in the atmosphere (e.g. Manabe and Wetherald 1967). In the troposphere, the increases in temperature and geopotential height over land are larger than over the ocean (Fig. 4d–e), resulting in positive thermodynamic and geopotential height contrasts. The positive changes in the tropospheric temperature and geopotential height contrasts are qualitatively consistent with the changes associated with the land–sea SAT contrast in the interannual variability (Fig. 4a, b).

However, some inconsistencies are not negligible between the interannual variabilities associated with the SAT contrast (Fig. 4a–c) and the linear trends (Fig. 4d–f). The tropospheric warming/stratospheric cooling contrast is not found in the interannual variability. This difference may influence partly the geopotential height and U orth in the upper troposphere and stratosphere. In addition, the trends in the tropospheric temperature, geopotential height and U orth over the ocean (140°E–160°E) are not similar to the interannual variabilities. The limited period (1979–2012) and large interannual variabilities over the Far East (Fig. 2c, see Sect. 4.3) make it hard to detect statistically significant trends. For example, most parts of the linear trends of the geopotential height and U orth are not statistically significant (Fig. 4e and f). We should also note that the linear trends of the tropospheric temperature and geopotential height contrast over land and ocean is much smaller (unit is 0.34 K−1, Fig. 4d, e) than those in the interannual variabilities (unit is 1 K−1, Fig. 4a, b). The consistencies between the interannual variabilities and the trends are limited to the signs in the land–sea contrasts of the tropospheric temperature and geopotential height (Fig. 4a, b, d, e).

4 Simulations of historical and future changes

4.1 Global changes in land–sea contrast

The observed variabilities in the thermodynamic and dynamic structures of the troposphere over the Far East are associated with the land–sea SAT contrast. We then examined the projected changes in surface and tropospheric land–sea contrast in the transient warming experiments in the CMIP5 models. Firstly we showed global characteristics of projected future changes in SAT and troposphere and then we compared gradual changes over East Asia in historical and future projections with observation (see Sects. 4.2 and 4.3).

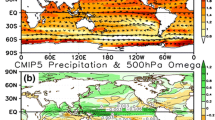

Figure 5 shows anomalies (Δ) of the JJA-mean SAT, Z3085 and Z eddy (hereafter ΔSAT, ΔZ3085 and ΔZ eddy , respectively) in RCP8.5 run (years 2071–2100) relative to the historical simulation (years 1851–1960). Warming is generally larger over land than over the ocean, indicating a positive land–sea SAT contrast in the warming climate. The formation of a positive SAT contrast is a robust feature among the four types of RCP runs detailed in Sect. 4.3. The positive change of ΔZ3085 over land is also larger than that over the ocean, particularly in the mid- and high-latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere (Europe, central and eastern Siberia, and North America), associated with increasing SAT contrast (Fig. 5c). In the lower latitude, some parts of spatial patterns of ΔZ3085 over ocean may be influenced by that of SST anomaly (larger over the central and eastern Pacific and the western Indian Ocean than the western Pacific and the eastern Indian Ocean). The all changes presented above are also found clearly in anomalies (years 111–140 relative to the control run) simulated in 1 % CO2 run (Fig. 5b, d), suggesting that the CO2 forcing is a dominant factor for the projected changes in RCP8.5 run. We mainly showed changes simulated in 1 % CO2 run hereafter and in Part II because it is easier to examine physical mechanisms than projected changes in the RCP runs forced by concentrations of trace gases, land use, and aerosols. The different settings of land use, concentrations of trace gases, and aerosols among the transient warming experiments (1 % CO2 and RCP runs) are factors for differences of the simulated changes among those runs (detailed in Sect. 4.3 and Part II).

Differences in JJA-mean climatology between a, c 30 years (2071–2100) in RCP8.5 run and 111 years (1850–1960) in the historical run and b, d 30 years (111–140) between 1 % CO2 and control runs in CMIP5 16-model ensemble means. a, b SAT normalized by global-mean ΔSAT (ΔSAT g , shade, K K−1). Contours represent normalized Z eddy 500 (interval = 2 m K−1). c, d Z3085 (shading, m K−1) and Z eddy 300 (contours, interval = 2 m K−1)

Figure 6 shows the consistency of ΔZ eddy 300 in the 16 models. The spatial patterns of positive and negative signs are largely consistent among the models; positive over mid-latitude central–eastern Eurasia and North America, and negative over Greenland to the mid-latitudes of Europe. The eastern sides of the continents in the Northern Hemisphere mid- and high-latitudes, including East Asia and eastern North America, are boundary areas between a positive anomaly over land and a negative anomaly over the ocean. In Sect. 4.2, we further examined changes in dynamical circulation and thermodynamic conditions in East Asia simulated in 16 models.

4.2 Changes in thermodynamic condition and atmospheric circulation over the Far East

Next we focus on the regional changes in the land–sea contrast over the Far East simulated in the CMIP5 models. Note that interannual variabilities over the Far East associated with the land–sea SAT contrast in the historical simulations conducted in the CMIP5 models generally show similar patterns to that in the observation (figures not shown).

Figure 7 shows changes in the geopotential height field and circulation over East Asia simulated in 1 % CO2 run. Both the multi-model ensemble means (Fig. 5) and their spreads in the RCP8.5 run are generally consistent with the 1 % CO2 run (Tables 1, 2). The larger tropospheric warming, as revealed by the large positive change in ΔZ3085 and the anticyclonic anomaly over central and eastern Siberia, results in an intensified land–sea thermal contrast over the Far East. Over the northern Japan, the horizontal winds in the lower troposphere show a change to northeasterly along the geopotential height contour. The patterns of the atmospheric circulation (northeasterly over the northern Japan and northwesterly over the western Japan) are similar to those of the observed variations associated with the interannual variability of the land–sea SAT contrast (Fig. 3c). Summertime precipitation over East Asia associated with Meiyu-Baiu rainband increases in the warmed climate (figure not shown) as examined well in previous studies (e.g. Kusunoki et al. 2011; Seo et al. 2013). In Fig. 7b, changes simulated in MIROC5 model which is used to examine scenario-dependencies of results (detailed below) are also shown. The ensemble-mean changes in 16 models presented above are generally consistent with simulated changes in MIROC5 model. The changes in land–sea ΔZ3085 contrast and atmospheric circulation over East Asia are generally larger in MIROC5 than the 16-model mean (Fig. 7; Tables 1, 2). However, simulated changes in 15-model ensemble mean excluding MIROC5 also show similar patterns (figure not shown), indicating the simulated changes in CMIP5 ensemble mean do not depend on the results of MIROC5 model (Fig. 6; Tables 1, 2).

Similar to Fig. 5c–d but for East Asia and the western North Pacific region. a CMIP5 16-model ensemble mean and b MIROC5. Vectors indicate normalized differences in horizontal wind (m s−1 K−1) at 850 hPa level. The wind vectors with wind speed ≤ 0.05 m s−1 K−1 are omitted for clarity

The vertical structures over East Asia, shown in Fig. 8, reveal a general warming throughout the troposphere and cooling or little change in the stratosphere, which are consistent with the observed trend shown in Fig. 4d. Note that the tropospheric warming in 1 % CO2 run is much larger than the observed 34-year trend in the reanalysis (Fig. 4d) because of larger amplitude of global warming in 1 % CO2 run (16-model mean of global-mean ΔSAT is 3.80 K, Table 2). Comparisons of gradual changes of tropospheric temperature between the models and reanalysis are detailed in Sect. 4.3. In the lower and middle troposphere, warming over the land is larger than the ocean, representing the land–sea warming contrast which is also consistent qualitatively with the trend (Fig. 4d) and the regression pattern (Fig. 4a) in the observation. Changes in land–sea geopotential height contrast (positive; Fig. 8b) and associated U orth (negative; Fig. 8c) also show same signs to the regressed fields in the lower and middle troposphere (Fig. 4b, c). The similarities of the responses in land–sea temperature and geopotential height contrast and atmospheric circulation to the regressed pattern in the lower and middle troposphere suggest that the parts of the projected future changes in the lower and middle troposphere reflect the structure of the interannual variability associated with the land–sea SAT contrast. In the upper troposphere (250–350 hPa), however, a strong warming and a negative land–sea warming contrast appear in the 1 % CO2 run, corresponding roughly to the future upper tropospheric warming projected by GCM simulations (e.g. Lorenz and DeWeaver 2007). The physical reasons for the changes in the upper troposphere are detailed in Part II. The different characteristic of the temperature change in upper troposphere and stratosphere from the regressed pattern may contribute to different responses of geopotential height and atmospheric circulation: general increase in geopotential height and anomalous southwesterly in lower stratosphere (Fig. 8b, c).

Similar to Fig. 4 but for differences in JJA-mean climatology between the 1 % CO2 and control runs in CMIP5 16-model ensemble means. a Normalized temperature (K K−1), b normalized geopotential height (m K−1), and c normalized U orth (m s−1 K−1). The line in b represents Z3085 (right axis, m K−1). Stipples denote regions where 12 out of 16 models agree on sign of the values plotted

4.3 Comparisons among different scenario simulations and with observation

The results presented above normalized by the land–sea SAT contrast (Figs. 3, 4a–c) or global-mean ΔSAT (Figs. 5, 6, 7, 8) are difficult to be compared each other. In this section, we compared modeled and observed changes in the indices of land–sea contrasts over the Far East. Figure 9 shows the time series of the observed and simulated land–sea contrasts; the latter taken from the historical, RCP8.5 and 1 % CO2 runs. The plotted time series are the observed JJA-mean, its 30-year running mean and the 16-model ensemble mean of modeled 30-year running means. The SAT and Z3085 land–sea contrasts in both the RCP8.5 and 1 % CO2 runs increase during the late twentieth to twenty-first century. These trends are qualitatively consistent with observation, although the observed increasing trend of the SAT contrast (0.11 K decade−1 in 1949–2010) is larger than the model ensemble average. Note that some parts of the observed trends are also influenced by decadal variations in the atmosphere and ocean (see Sect. 3.1). The observed interannual variability of the Z3085 contrast is large and the period of ERA-Interim is limited to only 34 years (1979–2012), leading to a positive but not statistically significant trend at the 90 % level (6.1 m decade−1). Nevertheless, its sign (positive) is clearly reproduced by GCMs, regardless of the idealized (1 % CO2) or realistic (historical and RCP) configuration.

Time series of 30-year running mean SAT land–sea contrast (K) over the Far East in a historical and RCP8.5 runs and b 1 % CO2 run in CMIP5 16 models. All values are anomalies from climatologies (1850–1960 in historical and RCP runs, 1949–1978 in HadCRUT4, and 1979–2012 in ERA-Interim). Curve and shade represent the 16-model ensemble mean and ±1 standard deviation. Light and dark blue curves in a are HadCRUT4 value and 30-year running mean. c, d Similar to a, b but for Z3085 contrast (m). Green curves in c are ERA-Interim value

Figure 10 shows the scenario dependency of the changes in land–sea contrast using the MIROC5 model. Note that the results of the MIROC5 model are generally similar to the ensemble means of the CMIP5 models, as described in Sect. 4.2. The observational data are also plotted for comparison (Fig. 10a, d). Shapes of some histograms are not smooth because of limited numbers of sample (e.g. RCP6.0 run). The histograms of the SAT and Z3085 contrasts and whickers of the RCP and 1 % CO2 runs shift rightward of the figures, indicating a general increase from those in the historical and control run (Fig. 10b, c, e, f). The modeled shifts of the SAT contrast in the RCP runs are relatively slower (Figs. 9a, 10) than those observed over 34 years (0.38 ± 0.39 K in 1983–2012 relative to 1949–1978), but the signs are consistent. Comparing the different scenarios, the changes in SAT and Z3085 contrast are larger in those scenarios in which stronger forcings are prescribed (namely, RCP2.6 < RCP4.5 < RCP6.0 < RCP8.5). These results indicate that: 1) the changes in the SAT and geopotential height contrast in different transient scenarios are qualitatively consistent; and 2) their magnitudes generally follow the strength of the prescribed forcing. Note that the spatial patterns of radiative forcing owing to the prescribed atmospheric compositions and land covers are different among the RCP runs, but that the intensities of the changes in land–sea contrasts are generally associated with the rates of global radiative forcing and warming (Table 3).

Histograms of a–c SAT land–sea contrasts (K). Whickers in the upper part of the panels indicate the means and the ranges of ±1 standard deviations in the periods. a 30-year (1949–1978 and 1983–2012) in HadCRUT4. b 111-year (1850–1960) in historical (gray) and 30-year (2071–2100) in RCP runs (yellow, green, blue and black are RCP2.6, 4.5, 6.0 and 8.5, respectively) simulated in the MIROC5 model (Table 3). c 30-year (111–140) in the control (gray) and 1 % CO2 (red) runs. d Z3085 contrast (m) in ERA-Interim (1979–2012) and e, f simulated in MIROC5

The results presented above are summarized in Fig. 11. The projected changes in the multi-model ensemble, in the RCP8.5 and 1 % CO2 runs and in the different RCP runs in the MIROC5 model, generally show increasing land–sea contrasts with notable intermodel variances (e.g. CNRM-CM5, CSIRO-Mk3-6-0 and MPI-ESM-MR show negative changes in Z3085 contrast in the RCP8.5 run, Table 1). In addition, the ensemble with a larger increase in SAT contrast shows a larger increase in Z3085 contrast in the multi-models and multi-RCP runs (the correlation coefficients of RCP8.5 and 1 % CO2 run among the 16 models are 0.64 and 0.75, respectively). Both the observed changes of SAT (1983–2012 relative to 1949–1978) and Z3085 contrasts (4.6 ± 28.6 m in 1996–2012 relative to 1979–1995) are qualitatively consistent with those of the modeled future changes (Fig. 9).

Changes in land–sea SAT (K) and Z3085 (m) contrasts in RCP and 1 % CO2 runs in MIROC5 and CMIP5 16-model. Gray crosses and circles represent averages and ±1 standard deviation of RCP8.5 run in ensemble-members in the individual models (Table 1). Small red crosses are 1 % CO2 run (Table 2). Large crosses are 16 models ensemble means and ±1 standard deviation in RCP8.5 (gray) and 1 % CO2 run (red). Gray and red lines indicate regression lines of 16-model ensembles in RCP8.5 and 1 % CO2 runs (correlation coefficients are 0.64 and 0.75, respectively). Small black marks are RCP runs in MIROC5 (Table 3)

5 Summary and discussion

Recent observational data show the increasing trend of land–sea SAT contrast over the Far East during boreal summer. This trend is consistent with the changes projected by the CMIP5 models in response to the increase of atmospheric CO2 concentration. The anomalous surface warming over the land relative to the ocean induces the land–sea thermal and geopotential height contrast throughout the troposphere, contributing to the anomalous circulation pattern (northeasterly) along the isobaric surface over East Asia. In the CMIP5 ensemble and four types of RCP runs based on a single GCM, the ensemble member with a larger change in SAT contrast tends to show the larger change in thickness contrast. The changes in the summertime atmospheric circulation pattern over East Asia can be interpreted as part of the response to the anomalous continental warming, relative to the ocean, under global warming.

The intermodel variances are not negligible among the CMIP5 models in terms of the projected future changes of land–sea contrast (Tables 1, 2; Figs. 9, 11). Some models show little change in land–sea contrast in the future projections. Previous studies have revealed that different models simulate different magnitudes of the global-mean land–sea SAT contrast under global warming (the ratio of land warming to ocean warming ranges between 1.3 and 1.8, Sutton et al. 2007; Joshi et al. 2008). The ratios of the land surface warming to the ocean warming in different models might differ because of different processes in the boundary layer and surface, ocean heat uptake in the sensitivity experiments, and simulated atmospheric conditions in the control runs (e.g. atmospheric circulation pattern, cloud and land surface properties). Differences in responses to the land-use changes and aerosol forcings among the models may also be important factors for the intermodel variances in the historical and RCP runs (e.g. Kumar et al. 2013). This study focused mainly on the ensemble mean of the changes in the land–sea thermal and thickness contrasts over the Far East. However, the ensemble mean is not necessarily the best estimate of climate change projection (e.g. Shiogama et al. 2011). It is meaningful to investigate the physical processes contributing to the intermodel variance of the magnitude in the land–sea contrast changes.

The responses over the Far East in the global warming experiments during boreal summer show some similarities to the interannual variabilities associated with the land–sea SAT contrast. Some previous studies also showed some similarities between projected future changes and interannual variabilities in other aspects of climate (e.g. Palmer 1999; Corti et al. 1999; Yamaguchi and Noda 2006; Arai and Kimoto 2008; Kosaka and Nakamura 2011). Palmer (1999) and Corti et al. (1999) discussed that changes in tropospheric circulation during boreal winter under global warming were caused by changes in residence frequency of regimes of the present-day climate. Arai and Kimoto (2008) also examined residence probability of global warming experiment in the climate regimes over East Asia during boreal summer compared with that of present-day simulation and showed a shift of interannual variability in a warmed climate using a single AGCM. However, some parts of the projected changes (e.g. the upper tropospheric warming) are not similar to the observed interannual variabilities as previous studies reported in other aspects of climate (e.g. Yamaguchi and Noda 2006; Kosaka and Nakamura 2011). The results of the present study reveal that the interannual variabilities cannot fully explain the projected future changes over the Far East but the land–sea contrast in the lower and middle troposphere are consistent qualitatively with the interannual variabilities of them associated with the land–sea SAT contrast.

The examination of land–sea contrast in this study might not explain all of the projected future changes over East Asia, during boreal summer, revealed in earlier studies. Particularly, influences from the south and west via teleconnection patterns from the tropics, subtropics and mid-latitude westerly, are important for both interannual variability and projected future changes in the East Asian climate (e.g. Sampe and Xie 2010; Kosaka and Nakamura 2011; Kosaka et al. 2011, Imada et al. 2013). The northeastward transport and convergence of water vapor over East Asia plays an essential role in the interannual variability and the projected future changes in the hydrological cycle and precipitation associated with the Meiyu-Baiu rainband (e.g. Kusunoki et al. 2011; Seo et al. 2013). The physical relationship between the projected change in land–sea contrast and Yamase activity (Endo 2012; Kanno et al. 2013), the Meiyu-Baiu rainfall, and the timings of Meiyu-Baiu onset and withdrawal (Kitoh and Uchiyama 2006; Inoue and Ueda 2012) should be confirmed in detail, paying particular attention to intra-seasonal timescales. It is interesting that observational data show some similarities with the results of the modeling studies (Hirota et al. 2005; Sato and Takahashi 2007; Endo 2011). The physical relationship between them and the observed and projected land–sea thermal contrast should be examined in future studies.

This study did not investigate in detail the physical mechanisms for the increase of the land–sea thermal contrast in the observational data and modeled future projections. Several previous studies have examined the physical processes of increasing land–sea SAT contrast under global warming and have revealed that the SST increase might be the major contributing factor (Joshi et al. 2008; Compo and Sardeshmukh 2009). In contrast, other studies have revealed that the land surface warming owing to the direct radiative effect of increasing CO2 concentration in the atmosphere, might play an important role for the future increase in land–sea contrast simulated by the GCMs (Kimoto 2005; Kamae and Watanabe 2013). In Part II, we examine the factors affecting the future changes in land–sea contrast over the Far East during boreal summer and demonstrate that another factor plays an essential role in the increasing land–sea contrast under global warming.

References

Adler RF, Huffman GJ, Chang A et al (2003) The Version-2 Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) monthly precipitation analysis (1979-present). J Hydrometeorol 4:1147–1167

Andrews T, Gregory JM, Webb MJ, Taylor KE (2012) Forcing, feedbacks and climate sensitivity in CMIP5 coupled atmosphere-ocean climate models. Geophys Res Lett 39:L09712. doi:10.1029/2012GL051607

Arai M, Kimoto M (2005) Relationship between springtime surface temperature and early summer blocking activity over Siberia. J Meteorol Soc Jpn 83:261–267

Arai M, Kimoto M (2008) Simulated interannual variation in summertime atmospheric circulation associated with the East Asian monsoon. Clim Dyn 31:435–447

Bayr T, Dommenget D (2013) The troposphere land–sea warming contrast as the driver of tropical sea level pressure changes. J Clim 26:1387–1402

Boer GJ (2011) The ratio of land to ocean temperature change under global warming. Clim Dyn 37:2253–2270

Compo GP, Sardeshmukh PD (2009) Oceanic influences on recent continental warming. Clim Dyn 32:333–342

Corti S, Molteni F, Palmer TN (1999) Signature of recent climate change in frequencies of natural atmospheric circulation regimes. Nature 398:799–801

Dee DP, Uppala SM, Simmons AJ et al (2011) The ERA-Interim reanalysis: configuration and performance of the data assimilation system. Q J Roy Meteorol Soc 137:553–597

Dommenget D (2009) The ocean’s role in continental climate variability and change. J Clim 22:4939–4952

Endo H (2011) Long-term changes of seasonal progress in Baiu rainfall using 109 years (1901–2009) daily station data. SOLA 7:5–8. doi:10.2151/sola.2011-002

Endo H (2012) Future changes of Yamase bringing unusually cold summers over Northeastern Japan in CMIP3 multi-models. J Meteorol Soc Jpn 90A:123–136

Fan L, Shin S-I, Liu Q, Liu Z (2013) Relative importance of tropical SST anomalies in forcing East Asian summer monsoon circulation. Geophys Res Lett 40:2471–2477. doi:10.1002/grl.50494

Fasullo J (2012) A mechanism for land–ocean contrasts in global monsoon trends in a warming climate. Clim Dyn 39:1137–1147

Hirota N, Takahashi M (2012) A tripolar pattern as an internal mode of the East Asian summer monsoon. Clim Dyn 39:2219–2238

Hirota N, Takahashi M, Sato N, Kimoto M (2005) Recent climate trends in the East Asia during the Baiu season of 1979–2003. SOLA 1:137–140. doi:10.2151/sola.2005-036

Imada Y, Watanabe M, Mori M, Kimoto M, Shiogama H, Ishii M (2013) Contribution of atmospheric circulation change to the 2012 heavy rainfall in southern Japan. In: Peterson T, Hoerling M, Stott P, Herring S (eds) Explaining extreme events of 2012 from a climate perspective. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 94:S52–S54

Inoue T, Ueda H (2012) Delay of the Baiu withdrawal in Japan under global warming condition with relevance to warming patterns of SST. J Meteorol Soc Jpn 90:855–868

Jin Q, Yang X-Q, Sun X-G, Fang J-B (2013) East Asian summer monsoon circulation structure controlled by feedback of condensational heating. Clim Dyn 41:1885–1897

Jones GS, Stott PA, Christidis N (2013) Attribution of observed historical near surface temperature variations to anthropogenic and natural causes using CMIP5 simulations. J Geophys Res 118:4001–4024. doi:10.1002/jgrd.50239

Joshi MM, Gregory JM, Webb MJ, Sexton DMH, Johns TC (2008) Mechanisms for the land–sea warming contrast exhibited by simulations of climate change. Clim Dyn 30:455–465

Kamae Y, Watanabe M (2012) On the robustness of tropospheric adjustment in CMIP5 models. Geophys Res Lett 39:L23808. doi:10.1029/2012GL054275

Kamae Y, Watanabe M (2013) Tropospheric adjustment to increasing CO2: its timescale and the role of land–sea contrast. Clim Dyn 41:3007–3024

Kamae Y, Watanabe M, Kimoto M, Shiogama H (2014) Summertime land–sea thermal contrast and atmospheric circulation over East Asia in a warming climate. Part II: Importance of CO2-induced continental warming. Clim Dyn (submitted)

Kanno H, Watanabe M, Kanda E (2013) MIROC5 predictions of Yamase (cold northeasterly winds causing cool summers in northern Japan). J Agri Meteorol 69:117–125

Kawamura R, Sugi M, Kayahara T, Sato N (1998) Recent extraordinary cool and hot summers in East Asia simulated by an ensemble climate experiment. J Meteorol Soc Jpn 76:597–617

Kimoto M (2005) Simulated change of the East Asian circulation under the global warming Scenario. Geophys Res Lett 32:L16701. doi:10.1029/2005GL023383

Kitoh A, Uchiyama U (2006) Changes in onset and withdrawal of the East Asian summer rainy season by multi-model global warming experiments. J Meteorol Soc Jpn 84:247–258

Kodama Y-M (1997) Airmass transformation of the Yamase air-flow in the summer of 1993. J Meteorol Soc Jpn 75:737–751

Kosaka Y, Nakamura H (2011) Dominant mode of climate variability, intermodel diversity, and projected future changes over the summertime Western North Pacific simulated in the CMIP3 models. J Clim 24:3935–3955

Kosaka Y, Xie S-P, Nakamura H (2011) Dynamics of interannual variability in summer precipitation over East Asia. J Clim 24:5435–5453

Kumar S, Dirmeyer PA, Merwade V et al (2013) Land use/cover change impacts in CMIP5 climate simulations: a new methodology and 21st century challenges. J Geophys Res 118:6337–6353

Kurashima A (1969) Reports on Okhotsk high-report of the annual meeting on forecasting technique for the year 1966. J Meteorol Res 21:170–193

Kusunoki S, Mizuta R, Matsueda M (2011) Future changes in the East Asian rain band projected by global atmospheric models with 20-km and 60-km grid size. Clim Dyn 37:2481–2493

Lambert FH, Chiang JCH (2007) Control of land–ocean temperature contrast by ocean heat uptake. Geophys Res Lett 34:L13704. doi:10.1029/2007GL029755

Li C, Yanai M (1996) The onset and interannual variability of the Asian summer monsoon in relation to land–sea thermal contrast. J Clim 9:358–375

Lorenz D, DeWeaver ET (2007) Tropopause height and zonal wind response to global warming in the IPCC scenario integrations. J Geophys Res 112:D10119. doi:10.1029/2006JD008087

Man W, Zhou T, Jungclaus JH (2012) Simulation of the East Asian summer monsoon during the last millennium with the MPI earth system model. J Clim 25:7852–7866

Manabe S, Wetherald RT (1967) Thermal equilibrium of the atmosphere with a given distribution of relative humidity. J Atmos Sci 24:241–259

Manabe S, Stouffer RJ, Spelman MJ, Bryan K (1991) Transient responses of a coupled ocean-atmosphere model to gradual changes of atmospheric CO2. Part I: annual mean response. J Clim 4:785–818

Mantua NJ, Hare SR (2002) The Pacific Decadal Oscillation. J Oceanogr 58:35–44

Meinshausen M, Smith SJ, Calvin K et al (2011) The RCP greenhouse gas concentrations and their extensions from 1765 to 2300. Clim Chang 109:213–241

Morice CP, Kennedy JJ, Rayner NA, Jones PD et al (2012) Quantifying uncertainties in global and regional temperature change using an ensemble of observational estimates: the HadCRUT4 data set. J Geophys Res 117:D08101. doi:10.1029/2011JD017187

Nakamura H, Fukamachi T (2004) Evolution and dynamics of summertime blocking over the Far East and the associated surface Okhotsk high. Q J Roy Meteorol Soc 130:1213–1234

Ninomiya K, Mizuno H (1985) Anomalously cold spell in summer over Northeastern Japan caused by northeasterly wind from polar maritime airmass. Part 1. EOF anslysis of temperature variation in relation to the large-scale situation causing the cold summer. J Meteorol Soc Jpn 63:845–857

Ninomiya K, Murakami T (1987) The early summer rainy season (Baiu) over Japan. In: Chang C-P, Krishnamurti TN (eds) Monsoon meteorology. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 93–121

Nitta T (1987) Convective activities in the tropical western Pacific and their impact on the Northern Hemisphere summer circulation. J Meteorol Soc Jpn 65:373–390

Palmer TN (1999) A nonlinear dynamical perspective on climate prediction. J Clim 12:575–591

Park Y-J, Ahn J-B (2014) Characteristics of atmospheric circulation over East Asia associated with summer blocking. J Geophys Res. doi:10.1002/2013JD020688

Sampe T, Xie S-P (2010) Large-scale dynamics of the Meiyu-Baiu rainband: environmental forcing by the westerly jet. J Clim 23:113–134

Sato N, Takahashi M (2007) Dynamical processes related to the appearance of the Okhotsk high during early midsummer. J Clim 20:4982–4994

Seo K-H, Ok J, Son J-H, Cha D-H (2013) Assessing future changes in the East Asian summer monsoon using CMIP5 coupled models. J Clim 26:7662–7675

Shiogama H, Emori S, Hanasaki N, Abe M, Masutomi Y, Takahashi K, Nozawa T (2011) Observational constraints indicate risk of drying in the Amazon basin. Nat Commun 2:253

Suda K, Asakura T (1955) A study on the unusual “Baiu” season in 1954 by means of Northern Hemisphere upper air mean charts. J Meteorol Soc Jpn 33:233–244

Sun Y, Ding Y, Dai A (2010) Changing links between South Asian summer monsoon circulation and tropospheric land–sea thermal contrasts under a warming scenario. Geophys Res Lett 37:L02704. doi:10.1029/2009GL041662

Sutton RT, Dong B-W, Gregory JM (2007) Land–sea warming ratio in response to climate change: IPCC AR4 model results and comparison with observations. Geophys Res Lett 34:L02701. doi:10.1029/2006GL028164

Tachibana Y, Iwamoto T, Ogi M, Watanabe Y (2004) Abnormal meridional temperature gradient and its relation to the Okhotsk high. J Meteorol Soc Jpn 82:1399–1415

Taylor KE, Stouffer RJ, Meehl GA (2012) An overview of CMIP5 and the experiment design. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 90:485–498

Trenberth KE, Jones PD, Ambenje P et al (2007) Observations: surface and atmospheric climate change. In: Solomon S et al (eds) Climate change 2007: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 235–336

Ueda H, Iwai A, Kuwako K, Hori ME (2006) Impact of anthropogenic forcing on the Asian summer monsoon as simulated by eight GCMs. Geophys Res Lett 33:L06703. doi:10.1029/2005GL025336

Ueda H, Kuroki H, Ohba M, Kamae Y (2011) Seasonally asymmetric transition of the Asian monsoon in response to ice age boundary conditions. Clim Dyn 37:2167–2179

Wakabayashi S, Kawamura R (2004) Extraction of major teleconnection patterns possibly associated with the anomalous summer climate in Japan. J Meteorol Soc Jpn 82:1577–1588

Wang Y (1992) Effects of blocking anticyclones in Eurasia in the rainy season (Meiyu/Baiu season). J Meteorol Soc Jpn 70:929–951

Wang B, Wu R, Lau K-M (2001) Interannual variability of the Asian summer monsoon: contrasts between the Indian and the western North Pacific-East Asian monsoons. J Clim 14:4073–4090

Wang B, Liu J, Kim H-J, Webster PJ, Yim S-Y, Xiang B (2013) Northern Hemisphere summer monsoon intensified by mega-El Niño/southern oscillation and Atlantic multidecadal oscillation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. doi:10.1073/pnas.1219405110

Watanabe M, Suzuki T, O’ishi R et al (2010) Improved climate simulation by MIROC5: mean states, variability, and climate sensitivity. J Clim 23:6312–6335

Wu G, Liu Y, He B, Bao Q, Duan A, Jin F–F (2012) Thermal controls on the Asian Summer Monsoon. Sci Rep 2:404. doi:10.1038/srep00404

Yamaguchi K, Noda A (2006) Global warming pattern over the North Pacific: ENSO versus AO. J Meteorol Soc Jpn 84:221–241

Yasunaga S, Hanawa K (2002) Regime shifts found in the Northern Hemisphere SST field. J Meteorol Soc Jpn 80:119–135

Yatagai A, Kamiguchi K, Arakawa O, Hamada A, Yasutomi N, Kitoh A (2012) APHRODITE: constructing a long-term daily gridded precipitation dataset for Asia based on a dense network of rain gauges. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 93:1401–1415

Zhu C, Wang B, Qian W, Zhang B (2012) Recent weakening of northern East Asian summer monsoon: a possible response to global warming. Geophys Res Lett 39:L09701. doi:10.1029/2012GL051155

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the World Climate Research Programme’s Working Group on Coupled Modeling, which is responsible for CMIP, and we thank the climate modeling groups (listed in Table 1) for producing and making available their model output. For CMIP5, the US Department of Energy’s Program for Climate Model Diagnosis and Intercomparison provided coordinating support, and led the development of the software infrastructure in partnership with the Global Organization for Earth System Science Portals. We would like to acknowledge Tokuta Yokohata, Tomoo Ogura and Seita Emori for providing helpful comments and suggestions. The authors are grateful to two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. This work was supported by the Program for Risk Information on Climate Change (SOUSEI program) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kamae, Y., Watanabe, M., Kimoto, M. et al. Summertime land–sea thermal contrast and atmospheric circulation over East Asia in a warming climate—Part I: Past changes and future projections. Clim Dyn 43, 2553–2568 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-014-2073-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-014-2073-0