Abstract

Habitat perturbations play a major role in shaping community structure; however, the elements of disturbance-related habitat change that affect diversity are not always apparent. This study examined the effects of habitat disturbances on species richness of coral reef fish assemblages using annual surveys of habitat and 210 fish species from 10 reefs on the Great Barrier Reef (GBR). Over a period of 11 years, major disturbances, including localised outbreaks of crown-of-thorns sea star (Acanthaster planci), severe storms or coral bleaching, resulted in coral decline of 46–96% in all the 10 reefs. Despite declines in coral cover, structural complexity of the reef framework was retained on five and species richness of coral reef fishes maintained on nine of the disturbed reefs. Extensive loss of coral resulted in localised declines of highly specialised coral-dependent species, but this loss of diversity was more than compensated for by increases in the number of species that feed on the epilithic algal matrix (EAM). A unimodal relationship between areal coral cover and species richness indicated species richness was greatest at approximately 20% coral cover declining by 3–4 species (6–8% of average richness) at higher and lower coral cover. Results revealed that declines in coral cover on reefs may have limited short-term impact on the diversity of coral reef fishes, though there may be fundamental changes in the community structure of fishes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Coral reefs are increasingly subject to a combination of natural and anthropogenic disturbances, which may threaten their extraordinary biodiversity (Jenkins 2003). Biodiversity, which herein refers to the number of species that coexist within a given area, is considered important because it provides for continuity of ecological function even after initial species losses (Naeem et al. 1994; Bellwood et al. 2004). Teleost fishes are an important component of coral reef ecosystems, fulfilling many critical ecological roles (McClanahan 2000; Bellwood et al. 2004; Dulvy et al. 2004), and are a major source of food and livelihood for people in tropical coastal areas (Pauly et al. 2002). Moreover, most reef fishes are closely associated with the reef substratum (Choat and Bellwood 1991), making them very susceptible to disturbances that alter the biological and/or physical structure of coral reef habitats (Wilson et al. 2006; Pratchett et al. 2008a, b). Understanding potential drivers of species richness for fishes is therefore, fundamental for ongoing management of coral reef habitats facing increasing frequency, severity and diversity of disturbances (Bellwood et al. 2004).

Most major disturbances on coral reefs (e.g., severe tropical storms, infestations of Acanthaster planci, and extreme changes in temperature or salinity) have direct effects on scleractinian corals, and the impact of these disturbances is often assessed as the extent of damage and mortality of scleractinian corals. On many reefs, there are long-term trends of declining coral cover caused by a combination of natural and direct anthropogenic disturbances (Gardner et al. 2003; Bruno and Selig 2007), which are being compounded by sustained and ongoing climate change (Hoegh-Guldberg 1999; Sheppard 2003; Wooldridge et al. 2005). Reduction in the availability of live coral directly affects the distribution and abundance of fishes that live, feed or recruit onto live corals (e.g., Williams 1986; Cheal et al. 2002; Halford et al. 2004). However, there are relatively few species that are specifically dependent on scleractinian corals (e.g., Munday et al. 2007) and the effects of disturbance may depend on how disturbances affect both coral cover and structural complexity (Garpe et al. 2006; Graham et al. 2006).

Interactions between habitat and coral reef fish have been intensely studied (e.g., McCormick 1995; Green 1996; Jennings et al. 1996; Munday et al. 1997; Friedlander and Parrish 1998; Chapman and Kramer 1999; Holbrook et al. 2000; McClanahan and Arthur 2001), and habitat alterations are likely to influence an array of fish species (Jones and Syms 1998). For example, acute reductions in coral cover are often accompanied by increases in algal abundance, which rapidly colonise the space vacated by live coral tissue (Diaz-Pulido and McCook 2002). Consequently, while loss of live coral may reduce resources for obligate coral feeders and dwellers, it may simultaneously improve conditions for species that feed on the epilithic algal matrix (EAM). Meta-analysis of 17 independent studies indicate EAM-feeding fish often increase in abundance following coral depletion (Wilson et al. 2006), and biomass of these fishes can be positively correlated to percent cover of turf algae (e.g., Williams and Polunin 2001), algal productivity (Russ 2003) and detritus quality (Wilson 2001). Thus, species lost from the coral-dependent group may be replaced by species with fundamentally different ecological roles without altering the species richness of the community (Bellwood et al. 2006b).

Previous studies have found that effects of disturbances on coral reef fishes are variable, some failing to detect a change in species richness (e.g., Walsh 1983; Shibuno et al. 1999; Adjeroud et al. 2002; Sheppard et al. 2002; Bellwood et al. 2006b), whereas others report declines in species richness (Halford et al. 2004; Jones et al. 2004; Sano 2004; Garpe et al. 2006; Graham et al. 2006). This disparity in results implies that disturbance does not necessarily cause a change in species richness and raises questions about the true drivers of diversity on reefs. Some disturbances, such as infestations of A. planci, coral disease and coral bleaching, kill scleractinian corals but leave the coral skeletons intact, whereas physical disturbances (e.g., storms and tsunamis) can cause loss of corals and reduce structural complexity (Wilson et al. 2006). Structural complexity provided by coral skeletons moderates key biological processes of competition and predation (Beukers and Jones 1997; Almany 2004) and may exert a much stronger influence on the abundance and diversity of reef fishes compared to loss of live coral tissue. Species richness of coral reef fishes is often strongly correlated with structural complexity of reef habitats (e.g., Risk 1972; Luckhurst and Luckhurst 1978), and experimental reductions of structural complexity ostensibly cause declines in species richness of fishes (Sano et al. 1984; Lewis 1997; Syms and Jones 2000). It follows, therefore, that if structural complexity is retained following a disturbance, the species richness of fish communities may be relatively unaffected.

The extent of habitat damage and initial reef condition will also influence fish responses to disturbance. It is often assumed that the relationship between coral cover and fish diversity is linear (e.g., Bell and Galzin 1984). However, Jones and Syms (1998) suggested that the relationship between disturbance intensity and community parameters, such as species richness, is only linear over a restricted range of disturbance intensities, and this relationship may be unimodal over the entire disturbance range. If the underlying relationship between coral cover and fish species richness is a saturating or unimodal function rather than being continuously linear, then the response of fish communities to disturbance will depend critically on start and end values of coral decline.

This study used data from annual surveys conducted over 11 years to assess the impact of different disturbances on the species richness of coral reef fishes on the Great Barrier Reef (GBR). Specifically, the study explored relationships between diversity of fishes, coral cover and topographic complexity. The two habitat variables are typically modified by severe tropical storms, coral bleaching and localised infestation of A. planci. It also examined how coral losses affected the functional composition of reef fish communities. Changes in community composition of fishes were considered for two groups most likely to be affected by changes in the biological and physical structure of coral reef habitats: coral-dependent fishes (including both obligate coral feeders and obligate coral-based species) and fishes that feed on the EAM. By examining relationships between species richness of key components of the fish community with coral cover and structural complexity, this study provides a thorough account of how habitat disturbance influences species richness of highly diverse reef fish communities.

Materials and methods

This study documents changes in coral cover, structural complexity and species richness of coral reef fishes at 10 reefs on the GBR (Table 1), each of which was subject to major disturbances (COTS outbreaks, severe storms or coral bleaching) during the course of the study. Disturbed reefs were selected from the 47 reefs, which are surveyed annually by the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) long term monitoring team and represent the reefs with the most severe declines in coral cover between 1995 and 2005. Disturbed reefs were located over a wide geographical area, and varied in latitude and position on the continental shelf (inner, mid and outer shelf). In addition, temporal variation in coral cover, structural complexity and species richness on three ‘control’ reefs were analysed, and results compared to those from disturbed reefs. The control reefs had not been subjected to any major disturbances and coral cover on each of these reefs had remained stable through the course of the study. Data on disturbed and control reefs were collected annually between 1995 and 2005 with two exceptions: Havannah Island, which was not surveyed before 1997; Thetford Reef, which was not surveyed in 2001.

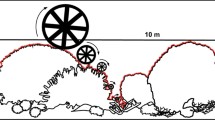

Sampling was conducted at three sites separated by 300–500 m on the northeast flank of each reef. At each site, coral cover and abundance of fishes were recorded along five replicate, permanently marked, 50 m transects at a depth of 6–9 m on the reef slope. A video camera, held ≈50 cm from the substratum, was used to record details of benthic composition along each transect. In addition, a 360° pan view of the surrounding reef was taken at the start of each transect, providing an overview of surrounding topography. Structural complexity of the habitat was assessed from these pan views, being scaled between 0 and 5, where 0 indicates no vertical relief, while reefs with exceptional complexity (with numerous caves and overhangs) were given a rating of 5 (see Polunin and Roberts 1993). This technique provides estimates that correlate well with other complexity measures (e.g., rugosity and reef height) and is strongly correlated with species richness of reef fish communities (Wilson et al. 2007). Coral cover was expressed as a percentage of substratum, estimated by recording the habitat under five points on each of the 40 systematically selected frames from each video transect (Abdo et al. 2003). Coral cover used in models and analyses was the mean cover at each site calculated from percentage coverage of all scleractinian corals as well as hydrozoans from the genus Millepora.

Composition of fish communities was assessed using underwater visual surveys. Presence and abundance of possibly 210 fish species from 10 families were recorded by a single observer from the AIMS long-term monitoring team passing along the same transects where the coral cover was assessed. For large mobile species the observer made a single pass over a transect of 5-m width, and for pomacentrids a single pass over a transect of 1 m width. Observers changed over time and for mobile or pomacentrid species; however, each observer was thoroughly trained in fish identification and standard survey procedures prior to collection of data (see Halford and Thompson 1996 for full survey details). Species richness estimates of fish communities were calculated by summing all the mobile and pomacentrid species recorded across the five transects at a site.

Fishes were placed into distinct ecological groupings (coral-based species, detritivore, excavator, facultative or obligate corallivore, grazer, invertivore, omnivore, piscivore, planktivore or scraper) based on their feeding habits, diet and habitat associations (Froese and Pauly 2007). The coral-dependent fishes included only those species that are obligate coral feeders (Pratchett 2005) or that have strong habitat associations with live coral (Wilson et al. 2008), herein referred to as coral-based feeders, whilst EAM-feeders included the functional groups: detritivores, excavators, grazers and scrapers.

Repeated measures ANOVAs was used to analyse changes in coral cover and species richness over time. Year and treatment (disturbed or control reefs) were entered as fixed effects and significant results were further investigated by carrying out repeated measures ANOVAs for reefs independently, followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. Structural complexity data were analysed using Kruskal–Wallis-ranked ANOVA. Normality and homogeneity of variances were examined using normal probability plots and Cochran’s test respectively. Complexity and species richness values were Log10 (x + 1) transformed and percent coral cover estimates were arcsine transformed when necessary to meet the assumptions of ANOVA. The assumption of sphericity was tested using Mauchly’s test and when the assumption was violated a Greenhouse-Geisser correction was used (Crowder and Hand 1990).

Temporal changes in the species richness of coral-dependent and EAM-feeding groups were compared on each reef to assess whether loss of coral-dependent species following disturbance was compensated by increases in EAM-feeding species. Change in species richness for both groups was calculated as the difference between annual estimates of coral-dependent or EAM-feeding species richness and the mean species richness of these groups at each reef over the 11 years of surveying. To assess the effect of coral loss on entire fish communities a principal components analysis (PCA) based on a correlation matrix was carried out using abundance data for all fish functional groups.

Mixed-effect modelling was used to identify the underlying relationships between the percentage of live coral cover and structural complexity of the benthos with the species richness of fish assemblages. Linear (y = a + b * x), log-linear (y = e^(a + b * ln(x)) and unimodal (y = a + b 1 * x 2 + b 2 * x) models, where y is the species richness, x the habitat variables and a and b the constants, were assessed and compared for the total assemblage, coral-dependent and EAM-feeding species. Specifically, a random-intercepts model was used, with random intercepts for sites nested within reefs. Visual inspection confirmed approximate normal distributions within groups for all variables. Model residuals were inspected for temporal autocorrelation and other violations of model assumptions, and an autoregressive component was included to model temporal autocorrelation in the data. Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) and Akaike Weights (wAIC) were used for model selection. To assess the level of support for each functional form of a predictor variable, wAIC values were summed across subsets of models containing that functional form of the variable (Burnham and Anderson 2002). Analyses were carried out using R version 2.4.1 (R Development Core Team 2006) with the package NLME version 3.1-78 for mixed-effects modelling (Pinheiro et al. 2006).

Results

Hard coral cover had declined significantly between 1995 and 2005 at all 10 disturbed reefs and remained stable at the three control reefs (significant interaction between time and treatment, Table 2). The rate of coral decline varied among disturbed reefs and was related to the type of disturbance. Where reefs were affected solely by storms, e.g., 19-131 and 19-138, coral decline was rapid and significant differences were detected within a year (Table 1, Fig. 1). In contrast, coral decline was protracted on reefs affected primarily by COTS, where significant declines in coral cover resulted from gradual declines across 3–4 consecutive years. The amount of live coral remaining after disturbances was also variable among reefs. Despite falling to 54% of the initial cover, coral cover at Reef 19-131 was still more than 30%, and although coral cover fell to 17% at Reef 19-138, it had returned to pre-disturbance levels by the end of this study (2005, Fig. 1). In contrast, coral cover fell to less than 5% on John Brewer, Rib, Gannett Cay, Havannah Island and Thetford Reefs and had not recovered to pre-disturbance levels by 2005.

Temporal variation in coral cover (solid line), structural complexity of habitat (bars) and species richness of fish assemblages (dotted line) on the 10 reefs subjected to severe coral depletion following disturbances and three control reefs. All values calculated at the site level and standard errors are calculated from n = 3 sites

Although live coral cover declined severely at all disturbed reefs, structural complexity only declined on five of these reefs (Fig. 1, Table 2). On most reefs, structural complexities was retained at reasonably high levels (>2), even after significant declines occurred. The exception was Havannah Island, where structural complexity had fallen to levels indicative of low lying and sparse cover by 1995. Live coral cover was positively related to structural complexity (F 1,148 = 132, P < 0.001), although coral cover accounted for only 24% of the variation in structural complexity across all reefs. On some reefs (e.g., Gannett Cay), coral and structural complexities were weakly correlated because coral skeletons remained in life position for several years after the death of the coral tissue and structural complexity was not affected. Even on those reefs where coral skeletons collapsed or were eroded, spur and groove systems, caves and crevices remained, ensuring that structural complexity remained moderately high. The one exception was Havannah Island. Coral bleaching in 1998, followed by a storm in 2000, resulted in high coral mortality followed by the collapse of the dead coral skeletons at Havannah Island. Unlike most of the other reefs under study, complexity of the underlying substrate at Havannah Island was low, and once the upright coral skeletons were reduced to rubble, the vertical relief became low and sparse, and structural complexity declined significantly (Table 2).

Despite declines in coral cover of 46–96%, species richness of fish communities remained stable on 7 of the 10 disturbed reefs and on all three of the control reefs. Importantly, species richness on control and disturbed reefs was similar throughout the 11 years of the study (Table 2), suggesting major changes in coral cover on the impacted reefs had not affected species richness. Independent assessments of reefs indicate that at Havannah Island species richness of the fish community was lower in 2002 and 2004 than it was in 1998, when coral cover and complexity were still high (Table 2). In contrast, at Low Isles, species richness was greater in 2004 than it was in 1995 and 1997, when coral cover was high. This was most likely due to a significant increase in the number of EAM-feeding fish species after the disturbance (Fig. 2, Table 2). Species richness of fishes was also variable at Reef 19-131, where the lowest estimates of richness occurred when coral cover was greatest (Fig. 1).

Changes in species richness of coral-dependent fishes (black bars) and EAM feeding fishes (white bars) relative to coral cover (solid line) at the 10 reefs subjected to severe coral depleting disturbances and three control reefs. All values calculated at the site level and standard errors are calculated from n = 3 sites at each reef

Species richness of coral-dependent species also varied on two of the three control reefs (Table 2), lower numbers of species occurring during 1995–1996 at Michaelmas and 2001 at Border Island. Low numbers of coral-dependent species on Michaelmas and Border Island corresponded to years when coral cover was lowest at these reefs (Table 1), and contributed to temporal differences between disturbed and control reefs (Table 2). Importantly, small variations in abundance of coral-dependent species did not affect species richness of the entire community.

Across all reef sites, coral-dependent fishes accounted for 12.7 ± 0.2% of the species encountered, whilst EAM-feeders accounted for 42.7 ± 0.4% of the species (mean ± SE). An increase in the species richness of coral-dependent fishes was associated with a decline in species richness of EAM-feeders, and vice versa (Fig. 2). However, a loss in coral-dependent species was often more than compensated for by a gain in EAM-feeding species. Annual changes in species richness of EAM-feeding fishes were typically <4 and the maximum shift in coral-dependent species was <3 (Fig. 2).

The relationship between coral cover and overall species richness was best described by a unimodal, rather than a linear model, as indicated by summed wAIC for models containing a unimodal coral cover relationship (wAIC = 0.94; see Table 3). These models suggested that richness of fish communities increases with coral cover, until coral cover reaches ~20%. Species richness then declines by three or four species (6–8% of average species richness for all reefs) at extremely high levels of coral cover. Coral cover was a better predictor of species richness than complexity alone (wAIC 0.31 vs. 0.00), and models containing structural complexity in addition to coral cover gained only moderate support (wAIC 0.68) relative to models containing only coral cover (wAIC 0.31). Failure to detect strong relationships between complexity and species richness is most likely due to limited variation in complexity values (co-efficient of variation 0.17), relative to coral cover (co-efficient of variation 0.64).

For coral-dependent species, a unimodal (wAIC 0.29) relationship with coral cover was indicated. Richness increased sharply as coral cover increased from very low levels but this rate of increase declined at moderate cover levels (Fig. 3). Thus, the decline in coral-dependent fish species with decreasing coral cover was most evident on those reefs where coral cover fell to extremely low levels and was less pronounced on those reefs where coral cover remained above 10% (Fig. 2). For example, on Reefs 19-131 and 19-138, where coral cover did not fall below 15%, species richness of coral-dependent species remained fairly constant; on other reefs, richness of these species fell when cover became extremely low (<5%). Again, structural complexity alone was a poor predictor of species richness of coral-dependent species and adding complexity to coral models gained only moderate support (wAIC 0.70 vs. 0.30). For EAM-feeding species a unimodal relationship with coral cover was supported (wAIC = 0.62, Fig. 3).

Shifts in fish communities following coral decline were still apparent when coral and EAM-dependent groups were subdivided and compared with abundances of fish in other functional groups. The first two components of a PCA explained 50% of the variation in abundance of fish groups (Fig. 4). The first axis was strongly correlated with the EAM-feeding groups, grazers and detritivores, whereas the second axis was correlated with both obligate coral feeders and coral-based feeders, which combined to form the coral-dependent group. The second axis is also highly correlated with planktivores, primarily because of the extremely high abundance of the two related species, Neopomacentrus azysron and Neopomacentrus bankieri, on reefs with high coral cover. Fish communities from different reefs formed distinct groups when plotted on the first two components, suggesting spatial variation in reef position and latitude strongly influences community composition. Within reefs, years with high coral cover were associated with high abundances of coral-dependent species. Interestingly, there is only one point in the bottom left-hand corner of the plot, suggesting a high abundance of coral-dependent and EAM-feeding species is uncommon. Low abundance of both these groups is, however, associated with low coral cover at Low Isles and Havannah Island.

Shifts in fish assemblages over 11 years on the 10 reefs subjected to severe coral depleting disturbances and three control reefs where coral cover remained stable over the same 11 years. Bi-plot of first two components of PCA above and eigenvectors of fish groups below. Each symbol represents community structure of coral reef fish on one reef, with one point for each year between 1995 and 2005. Size of each symbol is directly proportional to coral cover. Fac, facultative and Ob, obligate corallivores

Discussion

Coral cover and structural complexity are critical defining features of coral reef habitats, both of which may be significantly depleted by a range of different disturbances (Sano et al. 1987; Garpe et al. 2006; Graham et al. 2006). Corals inevitably contribute to reef structure; however, the relationships between coral cover and structural complexity are not always apparent, as structural complexity may decline several years after coral mortality (e.g., Graham et al. 2006). In this study, coral cover declined significantly on all the ten of the disturbed reefs, but structural complexity was affected on only five reefs (Fig. 1). An important aspect of this study was that many of the study sites were located on exposed reef slopes, where inherent complexities within the reef framework (e.g., caves and crevices) contributed most to structural complexity. Thus, the underlying topographic complexity at these sites is substantial and may be resistant to major disturbances, even after the breakdown of coral skeletons on the reef surface. The time scale for erosion of the actual reef framework may be hundreds or even thousands of years, though increasing ocean acidification may expedite this process (Hoegh-Guldberg et al. 2007). Nonetheless, ancient reefs retain facets of reef topography, even though coral cover and reef accretion has been negligible since the late quaternary (Harris et al. 2004). Similarly, reefs founded on granitic boulders retain some structural complexity even after extensive coral mortality and erosion of carbonate structures (Graham et al. 2007).

Havannah Island was distinctive among the 10 study reefs, in that structural complexity recorded in 1997 was provided by extensive stands of erect branching corals. As a result of bleaching-induced coral mortality in 1998, remaining skeletons gradually eroded until storm damage in 2000 reduced many of these to rubble. The length of time that structural complexity persists subsequent to disturbances will depend heavily on the rates of subsequent biological and physical erosion, versus coral recovery (Pratchett et al. 2008a). Within the study period, most of the reefs under study showed little or no coral recovery after the disturbance, yet structural complexity was often retained. This was most evident at Gannett Cay, where COTS outbreaks in 1997 led to declines in coral cover. However, the structural complexity, provided primarily by skeletons of branching Acropora spp., had remained intact over the ensuing eight years.

Despite the occurrence of major disturbances that significantly reduced coral cover on each of the 10 reefs, under study, species richness of fishes was largely unaffected on both the disturbed and control reefs. The only reef where there was evidence of a decline in the diversity of fishes was at Havannah Island, where declines in coral cover were accompanied by declines in structural complexity to levels lower than any other reef. These findings have important implications for conservation and management, as reefs that retain high structural complexity may be capable of sustaining high fish diversity, which is important for reef recovery (Bellwood et al. 2004). However, extensive coral loss may have long-term consequences for fish diversity, which will only become apparent during ongoing monitoring. Jones et al. (2004) suggested that declines in diversity following coral loss were partially attributable to reliance on living coral at earlier life history stages. This suggestion is supported by findings that coral association among juveniles is much higher than that among adult conspecifics of some reef fish (Feary et al. 2007; Garpe and Öhman 2007; Wilson et al. 2008). Up to 65% of fishes may be reliant on corals at settlement (Jones et al. 2004) suggesting that if coral recovery from disturbance is negligible, lagged declines in diversity of fishes may occur due to natural mortality combined with minimal population replenishment.

Structural complexity did not correlate well with species richness, most likely because of the limited variation in structural complexity over the 10-year study period. Consequently our study does not definitively identify structural complexity as a major determinant of diversity on reefs. In contrast, while variation in coral cover was extensive and a unimodal relationship between coral cover and species richness was apparent, this model accounted for an overall variation of only 2–4 species. Nonetheless, the model demonstrated that coral cover was a significant determinant of species richness on reef communities when cover was very low (<10%), but its influence was negligible beyond a certain threshold. This is consistent with the findings of Holbrook et al. (2006) who demonstrated once coral cover exceeded 10% in lagoonal sites at Moorea, French Polynesia differences between fish communities were much less apparent.

Species richness is, however, a simplistic measure of natural communities, and similarity in fish diversity on reefs with fundamentally different habitat structure may belie major changes in species composition of fish assemblages (Bellwood et al. 2006b). Major shifts in the species composition of fish assemblages were apparent following disturbances that reduced coral cover across the 10 disturbed reefs. Changes to the fish community following coral depletion were principally driven by a decline in coral-dependent fishes and increases in EAM-feeding species. Fluctuations in species richness of coral-dependent and EAM-feeders were however small with maximum species replacement of <4 species each year. Moreover, species richness of coral-dependent and EAM-feeding species varied by less than four and six species respectively, despite extensive changes in coral cover (60%). Consequently, although changes in the abundance of coral-dependent and EAM-feeding species often accounted for shifts in community composition, reciprocal replacement of species between these groups played a minor role in maintaining species richness of the community.

The replacement of coral-dependent species with EAM-feeders following disturbance contributes to our understanding of resilience mechanics on coral reefs. EAM-feeding species are expected to prevent the expansion of macroalgae and maintain surfaces suitable for future coral settlement, preventing phase shifts from coral to algal dominated reefs (Hughes et al. 2007; Mumby et al. 2007). Differing feeding modes and subtle variation in the diet of EAM-feeders imply different ecological roles (Wilson et al. 2003; Bellwood et al. 2006a; Ledlie et al. 2007; Mantyka and Bellwood 2007), and the presence of a greater diversity of EAM-feeding species following disturbances suggests comprehensive maintenance of reef surfaces suitable for recovery. Thus, species redundancy within a broad functional group such as the EAM-feeders may be low and recovery of reefs may depend in part on colonisation by a broad suite of EAM-feeders following disturbances.

Results of this study clearly demonstrate that a decline in coral cover does not necessarily lead to a decline in structural complexity or species richness of coral reef fishes. Coral cover varied from 0 to 60%, yet species richness of the fish community changed by only 6–8%. The relationship between coral cover and species richness was best explained by a unimodal model. When coral cover was low, a loss of coral-dependent species was compensated for by an increase in EAM-feeders. Conversely, at very high coral cover, species richness may have declined slightly, as increases in the diversity of coral-dependent species did not fully compensate for the declining richness of EAM-feeders. This replacement of guilds helps to keep species richness at equilibrium and is an important mechanism of reef recovery. However, changes in coral-dependent and EAM-feeding species involved only a small portion of the species in the fish community and could not account for sustained species richness after extensive coral mortality. Instead, continuity of species richness within fish communities may be partially attributed to the persistence of high reef structural complexity, which may be retained indefinitely on those reefs where underlying reef framework complexity is high.

References

Abdo D, Burgess S, Coleman G, Osborne K. (2003) Surveys of benthic reef communities using underwater video. Long term monitoring of the Great Barrier Reef, Standard Operating Procedure No. 9. Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville

Adjeroud M, Augustin D, Galzin R, Salvat B (2002) Natural disturbances and interannual variability of coral reef communities on the outer slope of Tiahura (Moorea, French Polynesia): 1991 to 1997. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 237:121–131

Almany GR (2004) Differential effects of habitat complexity, predators and competitors on abundance of juvenile and adult coral reef fishes. Oecologia 141:105–113

Bell JD, Galzin R (1984) Influence of live coral cover on coral-reef fish communities. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 15:265–274

Bellwood DR, Hughes TP, Folke C, Nyström M (2004) Confronting the coral reef crisis. Nature 429:827–833

Bellwood DR, Hughes TP, Hoey AS (2006a) Sleeping functional group drives coral reef recovery. Curr Biol 16:2434–2439

Bellwood DR, Hoey AS, Ackerman JL, Depczynski M (2006b) Coral bleaching, reef fish community phase shifts and the resilience of coral reefs. Global Change Biol 12:1–8

Beukers JS, Jones GP (1997) Habitat complexity modifies the impact of piscivores on a coral reef population. Oecologia 114:50–59

Bruno JF, Selig ER (2007) Regional decline of coral cover in the Indo-Pacific: timing, extent, and subregional comparisons. PLoS One 8:e711

Burnham K, Anderson D (2002) Model selection and multimodel inference: a practical information-theoretic approach. Springer, New York

Chapman MR, Kramer DL (1999) Gradients in coral reef fish density and size across the Barbados Marine Reserve boundary: Effects of reserve protection and habitat characteristics. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 181:81–96

Cheal AJ, Coleman G, Delean S, Miller I, Osborne K, Sweatman H (2002) Responses of coral and fish assemblages to a severe but short-lived tropical cyclone on the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Coral Reefs 21:131–142

Choat JH, Bellwood DR (1991) Reef fishes: their history and evolution. In: Sale PF (ed) The ecology of fishes on coral reefs. Academic Press, San Diego, pp 39–66

Crowder MJ, Hand DJ (1990) Analysis of repeated measures. Chapman and Hall, New York

Diaz-Pulido G, McCook LJ (2002) The fate of bleached corals: patterns and dynamics of algal recruitment. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 232:115–128

Dulvy NK, Freckleton RP, Polunin NVC (2004) Coral reef cascades and the indirect effects of predator removal by exploitation. Ecol Lett 7:410–416

Feary DA, Almany GR, McCormick MI, Jones GP (2007) Habitat choice, recruitment and the response of coral reef fishes to coral degradation. Oecologia 153:727–737

Friedlander AM, Parrish JD (1998) Habitat characteristics affecting fish assemblages on a Hawaiian coral reef. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 224:1–30

Froese R, Pauly D (2007) FishBase. World Wide Web electronic publication. www.fishbase.org

Gardner TA, Cote IM, Gill JA, Grant A, Watkinson AR (2003) Long-term region-wide declines in Caribbean corals. Science 301:958–960

Garpe KC, Öhman MC (2007) Non-random habitat use by coral reef fish recruits in Mafia Island Marine Park. Afr J Mar Sci 29:18–199

Garpe KC, Yahya SAS, Lindahl U, Öhman MC (2006) Long-term effects of the 1998 coral bleaching event on reef fish assemblages. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 315:237–247

Graham NAJ, Wilson SK, Jennings S, Polunin NVC, Bijoux JP, Robinson J (2006) Dynamic fragility of oceanic coral reef ecosystems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:8425–8429

Graham NAJ, Wilson SK, Jennings S, Polunin NVC, Robinson J, Daw T (2007) Lag effects in the impacts of mass coral bleaching on coral reef fish, fisheries and ecosystems. Conserv Biol 21:1291–1300

Green AL (1996) Spatial, temporal and ontogenetic patterns of habitat use by coral reef fishes (family Labridae). Mar Ecol Prog Ser 113:1–11

Halford AR, Thompson AA (1996) Visual census surveys of reef fish. Long term monitoring of the Great Barrier Reef, Standard Operating Procedure No. 3. Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville

Halford A, Cheal AJ, Ryan D, DMcB Williams (2004) Resilience to large-scale disturbance in coral and fish assemblages on the Great Barrier Reef. Ecology 85:1892–1905

Harris PT, Heap AD, Wassenberg T, Passlow V (2004) Submerged coral reefs in the Gulf of Carpentaria, Australia. Mar Geol 207:185–191

Hoegh-Guldberg O (1999) Climate change, coral bleaching and the future of the world’s coral reefs. Mar Freshw Res 50:839–866

Hoegh-Guldberg O, Mumby PJ, Hooten AJ, Steneck RS, Greenfield P, Gomez E, Harvell CD, Sale PF, Edwards AJ, Caldeira K, Knowlton N, Eakin CM, Iglesias-Prieto R, Muthiga N, Bradbury RH, Dubi A, Hatziolos ME (2007) Coral reefs under rapid climate change and ocean acidification. Science 318:1737–1742

Holbrook SJ, Forrester GE, Schmitt RJ (2000) Spatial patterns in abundance of a damselfish reflect availability of suitable habitat. Oecologia 122:109–120

Holbrook SJ, Brooks AJ, Schmitt RJ (2006) Relationships between live coral cover and reef fishes: implications for predicting effects of environmental disturbances. Proc 10th Int Coral Reef Symp 1:241–249

Hughes TP, Rodrigues MJ, Bellwood DR, Ceccerelli D, Hoegh-Guldberg O, McCook L, Moltchaniwskyj N, Pratchett MS, Steneck RS, Willis BL (2007) Phase shifts, herbivory and the resilience of coral reefs to climate change. Curr Biol 17:360–365

Jenkins M (2003) Prospects for biodiversity. Science 302:1175–1177

Jennings S, Boulle DP, Polunin NVC (1996) Habitat correlates of the distribution and biomass of Seychelles reef fishes. Environ Biol Fish 46:15–25

Jones GP, Syms C (1998) Disturbance, habitat structure and the ecology of fishes on coral reefs. Aust J Ecol 23:287–297

Jones GP, McCormick MI, Srinivasan M, Eagle JV (2004) Coral decline threatens fish biodiversity in marine reserves. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:8251–8253

Ledlie MH, Graham NAJ, Bythell JC, Wilson SK, Jennings S, Polunin NVC, Hardcastle J (2007) Phase shifts and the role of herbivory in the resilience of coral reefs. Coral Reefs 26:641–653

Lewis AR (1997) Effects of experimental coral disturbance on the structure of fish communities on large patch reefs. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 161:37–50

Luckhurst BE, Luckhurst K (1978) Analysis of the influence of substrate variables on coral reef fish communities. Mar Biol 49:317–323

McClanahan TR (2000) Recovery of a coral reef keystone predator, Balistapus undulatus, in East African marine parks. Biol Conserv 94:191–198

McClanahan TR, Arthur R (2001) The effect of marine reserves and habitat on populations of east African coral reef fishes. Ecol Appl 11:559–569

McCormick MI (1995) Fish feeding on mobile benthic invertebrates: influence of spatial variability in habitat associations. Mar Biol 121:627–637

Mantyka CS, Bellwood DR (2007) Direct evaluation of macroalgal removal by herbivorous coral reef fishes. Coral Reefs 26:435–442

Mumby PJ, Harborne AR, Williams J, Kappel CV, Brumbaugh DR, Micheli F, Holmes KE, Dahlgren CP, Paris CB, Blackwell PG (2007) Trophic cascade facilitates coral recruitment in a marine reserve. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:8362–8367

Munday PL, Jones GP, Caley MJ (1997) Habitat specialisation and the distribution and abundance of coral-dwelling gobies. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 152:227–239

Munday PL, Jones GP, Sheaves M, Williams AJ, Goby G (2007) Vulnerability of fishes on the Great Barrier Reef to climate change. In: Johnson J, Marshall P (eds) Climate change and the Great Barrier Reef.: Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, Townsville, pp 357–391

Naeem S, Thompson LJ, Lawler SP, Lawton JH, Woodfin RM (1994) Declining biodiversity can alter the performance of ecosystems. Nature 368:734–737

Pauly D, Christensen V, Guénette S, Pitcher TJ, Rashid Sumaila U, Walters CJ, Watson R, Zeller D (2002) Towards sustainability in world fisheries. Nature 418:689–695

Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D (2006) nlme: Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R package version 3.1–79

Polunin NVC, Roberts CM (1993) Greater biomass and value of target coral-reef fishes in two small Caribbean marine reserves. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 100:167–176

Pratchett MS (2005) Dietary overlap among coral-feeding butterflyfishes (Chaetodontidae) at Lizard Island, northern Great Barrier Reef. Mar Biol 148:373–382

Pratchett MS, Wilson SK, Graham NAJ, Munday PL, Jones GP, Polunin NVC (2008a) Effects of coral bleaching on motile reef organisms: current knowledge and the long-term prognosis. In: Lough J, van Oppen M (eds) Coral bleaching: patterns, processes, causes and consequences. Springer, Dordrecht

Pratchett MS, Munday PL, Wilson SK, Graham NAJ, Cinner JE, Bellwood DR, Jones GP, Polunin NVC, McClanahan TR (2008b) Effects of climate-induced coral bleaching on coral-reef fishes: ecological and economic consequences. Oceanogr Mar Biol Annu Rev 46:251–296

R Development Core Team (2006) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. http://www.R-project.org

Risk MJ (1972) Fish diversity on a coral reef in the Virgin Islands. Atoll Res Bull 153:1–6

Russ GR (2003) Grazer biomass correlates more strongly with production than with biomass of algal turfs on a coral reef. Coral Reefs 22:63–67

Sano M (2004) Short-term effects of a mass coral bleaching event on a reef fish assemblage at Iriomote Island, Japan. Fish Sci 70:41–46

Sano M, Shimizu M, Nose Y (1984) Changes in structure of coral reef fish communities by destruction of hermatypic corals—observational and experimental views. Pac Sci 38:51–79

Sano M, Shimizu M, Nose Y (1987) Long-term effects of destruction of hermatypic corals by Acanthaster planci infestation on reef fish communities at Iriomote Island, Japan. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 37:191–199

Sheppard CRC (2003) Predicted recurrences of mass coral mortality in the Indian Ocean. Nature 425:294–297

Sheppard CRC, Spalding S, Bradshaw C, Wilson S (2002) Erosion vs. recovery of coral reefs after 1998 El Niño: Chagos reefs, Indian Ocean. Ambio 31:40–48

Shibuno T, Hashimoto K, Abe O, Takada Y (1999) Short-term changes in structure of a fish community following coral bleaching at Ishigaki Island, Japan. Galaxea 1:51–58

Sweatman H, Abdo D, Burgess S, Cheal A, Coleman G, Delean S, Emslie M, Miller I, Osborne K, Oxley W, Page C, Thompson A (2003) Long-term monitoring of the Great Barrier Reef. Status Report 6. Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville

Syms C, Jones GP (2000) Disturbance, habitat structure, and the dynamics of a coral-reef fish community. Ecology 81:2714–2729

Walsh WJ (1983) Stability of a coral reef fish community following a catastrophic storm. Coral Reefs 2:49–63

Williams DM (1986) Temporal variation in the structure of reef slope fish communities (central Great Barrier Reef): short term effects of Acanthaster planci infestations. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 28:157–164

Williams ID, Polunin NVC (2001) Large-scale associations between macroalgal cover and grazer biomass on mid-depth reefs in the Caribbean. Coral Reefs 19:358–366

Wilson SK (2001) Multiscale habitat associations of detrivorous blennies (Blenniidae: Salariini). Coral Reefs 20:245–251

Wilson SK, Bellwood DR, Choat JH, Furnas M (2003) Detritus in the epilithic algal matrix and its use by coral reef fishes. Oceanogr Mar Biol Annu Rev 41:279–309

Wilson SK, Graham NAJ, Pratchett MS, Jones GP, Polunin NVC (2006) Multiple disturbances and the global degradation of coral reefs: are reef fishes at risk or resilient? Global Change Biol 12:2220–2234

Wilson SK, Graham NAJ, Polunin NVC (2007) Appraisal of visual assessments of habitat complexity and benthic composition on coral reefs. Mar Biol 151:1069–1076

Wilson SK, Burgess S, Cheal A, Emslie M, Fisher R, Miller I, Polunin NVC, Sweatman HPA (2008) Habitat utilisation by coral reef fish: implications for specialists vs. generalists in a changing environment. J Anim Ecol 77:220–228

Wooldridge S, Done T, Berkelmans R (2005) Precursors for resilience in coral communities in a warming climate: a belief network approach. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 295:157–169

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the members of the long-term monitoring team at the Australian Institute of Marine Science who collected coral and fish data, and crews from the RV Harry Messel, Cape Ferguson and Lady Basten who provided support in the field. The manuscript was improved by comments from NAJ Graham and R Fisher and two anonymous reviewers. Financial support from the Leverhulme trust was provided to SKW.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Biology Editor Dr Mark McCormick

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Wilson, S.K., Dolman, A.M., Cheal, A.J. et al. Maintenance of fish diversity on disturbed coral reefs. Coral Reefs 28, 3–14 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-008-0431-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-008-0431-2