Abstract

Exposure of coral reefs to river plumes carrying increasing loads of nutrients and sediments is a pressing issue for coral reefs around the world including the Great Barrier Reef (GBR). Laboratory experiments were conducted to investigate the effects of changes in inorganic nutrients (nitrate, ammonium and phosphate), salinity and various types of suspended sediments in isolation and in combination on rates of fertilisation and early embryonic development of the scleractinian coral Acropora millepora. Dose–response experiments showed that fertilisation declined significantly with increasing sediments and decreasing salinity, while inorganic nutrients at up to 20 μM nitrate or ammonium and 4 μM phosphate had no significant effect on fertilisation. Suspended sediments of ≥100 mg l−1 and salinity of 30 ppt reduced fertilisation by >50%. Developmental abnormality occurred in 100% of embryos at 30 ppt salinity, and no fertilisation occurred at ≤28 ppt. Another experiment tested interactions between sediment, salinity and nutrients and showed that fertilisation was significantly reduced when nutrients and low concentrations of sediments co-occurred, although both on their own had no effect on fertilisation rates. Similarly, while slightly reduced salinity on its own had no effect, fertilisation was reduced when it coincided with elevated levels of sediments or nutrients. Both these interactions were synergistic. A third experiment showed that sediments with different geophysical and nutrient properties had differential effects on fertilisation, possibly related to sediment and nutrient properties. The findings highlight the complex nature of the effects of changing water quality on coral health, particularly stressing the significance of water quality during coral spawning time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

One of the most pressing concerns for the management of the Great Barrier Reef (GBR) is to understand the consequences of increasing terrestrial runoff of nutrients and sediments (Hutchings and Haynes 2005; Hutchings et al. 2005). Nearshore reefs of the GBR have developed in an environment driven by the influence of river runoff, yet in the past 150 years, expanding agriculture, urban development and industry have led to greater runoff of freshwater (McCulloch et al. 2003), nutrients (Devlin et al. 2001; Furnas 2003), sediments (Neil et al. 2002; Furnas 2003; McCulloch et al. 2003), and agrochemicals (Haynes and Johnson 2000; Haynes and Michalek-Wagner 2000). River plume waters are characterised by elevated levels of dissolved organic and inorganic nitrogen and phosphorus, suspended particulate matter, turbidity, and chlorophyll a, as well as by reduced salinity, when compared with ambient marine coastal waters (Table 1). Generally, flood plumes in this region remain within 20 km of the coast due to prevailing south-easterly winds and Coriolis forcing (Chao 1988), impinging upon the approximately 900 nearshore reefs (~27% of all reefs) within the GBR Marine Park. In the absence of strong south-easterly winds, flood plumes may extend to some of the mid- and outer-shelf reefs of the GBR (Devlin and Brodie 2005).

Some reefs in the northern wet tropical section of the GBR (Herbert to Daintree Rivers) are exposed to floods nearly annually. Reefs in the southern, central and far northern sections are characterised by dryer subtropical to tropical climates with fewer floods (on average every 2–3 years; Devlin and Brodie 2005). The majority of river floods occur in the monsoonal wet season (October to April), often associated with tropical cyclones or rain depressions (Devlin et al. 2001). Although average rainfall is highest in January to March, early floods can coincide with the coral mass spawning event in the GBR that occurs annually in October to December (Babcock et al. 1986).

The residency time of dissolved materials in the GBR has been estimated to be up to 300 days (disregarding biological uptake; Luick et al. 2007), while particulate materials remain for an unknown period whilst undergoing cycles of wind-driven re-suspension and deposition until they are finally deposited in deeper water or in north-facing bays. Terrestrial runoff therefore not only affects biological processes during acute flood events but can also chronically alter water quality near inshore reefs year-round.

The reproductive processes and early life history stages of corals, including fertilisation, embryonic development, metamorphosis and settlement, are sensitive to changes in water quality (Fabricius 2005). Successful coral reproduction is critical for the resilience of coral reefs, determining the speed of recovery after disturbance. Several investigators have studied the effects of individual water quality parameters on coral reproduction. In particular, exposure to increased levels of nitrogen and phosphorus resulted in reduced fertilisation rates and increased levels of developmental abnormalities in Acropora longicyathus (Harrison and Ward 2001), as well as the production of smaller and fewer eggs per polyp in A. longicyathus and Acropora aspera (Ward and Harrison 2000). Enhanced ammonium has also been shown to reduce larval survival and settlement in Diploria strigosa with more pronounced reductions at higher temperatures (Bassim and Sammarco 2003). Reduction in salinity from 35 to 28 ppt reduced fertilisation success in Acropora digitifera from 86% to 25%, with a further 50% reduction in development to actively swimming planulae larvae (Richmond 1993). Suspended sediments of 50–100 mg l−1 have also been shown to reduce fertilisation rates, larval survival and larval settlement in Acropora digitifera (Gilmour 1999).

Understanding the effects of changes in water quality on coral reproduction is complicated by the fact that high nutrients often co-occur with reduced salinity and increased levels of suspended sediments. Few studies have examined these interactive effects between water quality parameters on coral reproduction. One of the few studies to investigate interactions in water quality parameters on corals is that of Bassim and Sammarco (2003) who showed that the effects of temperature and ammonium were additive in reducing survivorship, ciliary activity and settlement rates of larvae of the coral Diploria strigosa. Another study showed that the effects of sedimentation on adult corals depended upon the physical and chemical properties of the sediments, as nutrient-rich sediments exerted greater photo-physiological stress on corals than nutrient-poor sediments (Weber et al. 2006). The effects of sedimentation on the photo-physiology of reef-inhabiting crustose coralline algae were also substantially exacerbated by the presence of trace concentrations of the herbicide diuron (Harrington et al. 2005).

This study investigates the synergistic effects of varying but environmentally relevant levels of suspended sediments, salinity and dissolved inorganic nitrogen (as nitrate and ammonium) and phosphorus on fertilisation and embryonic development in the coral Acropora millepora. The effects of five contrasting sediment types on coral fertilisation and development were also compared, to better understand how sediment properties determine reproductive impairment. The results help to better understand the effects of increased terrestrial runoff and changes in water quality on coral reproduction and resilience on coral reef systems that are within the reach of river flood plumes and seafloor resuspension on the GBR.

Materials and methods

Spawning and gamete collection

The broadcast-spawning coral Acropora millepora (Ehrenberg, 1834), abundant in nearshore waters of the GBR, was selected as the study species. Eleven gravid colonies (each ~30 × 30 cm) were collected from Davies Reef, GBR (18°50′ S, 147°38′ E), from a depth of 5–8 m on 28 Nov. 2004. They were transported to aquarium facilities at the Australian Institute of Marine Science and maintained outdoors in 27–29°C temperature-controlled, flow-through seawater tanks until spawning commenced.

Prior to sunset, colonies were isolated in 50 l plastic containers and shielded from artificial light. Synchronous spawning occurred in 8 of the 11 colonies between 2100 and 2200 h on 1 Dec. 4 days after the full moon. The released gametes were collected following the methods of Negri and Heyward (2000). Briefly, the floating egg–sperm bundles from individual colonies were collected from the water surface by gentle suction through a plastic tube into 250 ml plastic containers. Gametes from each colony were kept separate to prevent fertilisation until the experiments were ready to proceed. Gametes in the plastic jars were gently agitated to separate the eggs and sperm, and passed through a 150 μm plankton mesh to retain all eggs and collect the concentrated sperm in a glass beaker. The eggs thus retained on the mesh were washed five times with sperm-free seawater to remove residual sperm. Eggs from all colonies that had spawned were pooled, as was the concentrated sperm.

The sperm concentration in the stock solution was determined with a haemocytometer viewed with a compound microscope at 400× magnification. Sperm concentration was diluted with sperm-free seawater to achieve a working stock of ~1.4 × 107 cells ml−1. The concentrations of the egg and sperm slurries were adjusted to obtain ~100–500 eggs and a sperm concentration of ~2 × 106 sperm ml−1 per treatment chamber. This concentration has been found to be slightly suboptimal for fertilisation, thereby increasing the sensitivity of the assay (Harrison and Ward 2001). Gamete-free seawater treatments with varying concentrations of dissolved inorganic nutrients, various types of sediments and/or freshwater (see below) were made up a few hours prior to spawning in 70 ml plastic jars. To each of five replicate jars holding 20 ml of modified seawater per treatment, 5 ml of egg solution was added, and 5 ml of sperm was added to another set of five plastic jars per treatment. Gametes remained in separate jars for 30 min before the eggs and sperm from the appropriate treatments were combined, resulting in a final gamete and seawater volume of 50 ml per chamber. The 30 min pre-fertilisation exposure period simulated the time required for sperm to find and appropriate eggs in the field, and reflecting the time required for polar body extrusion in acroporid gametes (Babcock and Heyward 1986). Chambers were sealed and then placed in a flow-through seawater bath to maintain a constant ambient temperature during fertilisation and development. At 10 min intervals all chambers were gently agitated to keep the sediment in suspension.

Development was terminated after 3 h by adding to each jar 2 ml of Bouin’s preservative (75 ml saturated aqueous picric acid, 25 ml concentrated formalin, 5 ml glacial acetic acid), which preserved embryo integrity. Three aliquots of fertilised eggs were then collected with a wide bore pipette, placed on glass well-slides, and photographed for later analysis of rates of fertilisation, abnormal and normal development (both expressed as a percentage of fertilised eggs). Coral embryos undergo radial holoblastic cleavage with regular cleavage up to the eight cell stage which generally occurs within 3–8 h (Hayashibara et al. 1997; Ball et al. 2002; Okubu and Motokawa 2007). Aberrant development was characterised as deviation from this pattern of division, generally resulting in irregularly shaped blastomeres.

Treatment types

Three experiments were conducted. Experiment 1 investigated the main effects of gamete exposure to increasing concentrations of suspended sediments, salinity, and dissolved inorganic nitrogen and phosphate. Experiment 2 investigated the combined effects of suspended sediment, salinity and nutrients, to assess potential interactions. Experiment 3 investigated main effects of increasing concentrations of five different types of sediments. Concentrations for all the treatments were within the range of those measured on nearshore reefs of the GBR during flood events (Devlin et al. 2001).

Experiment 1: response curves

Suspended sediment

Coastal sediment was collect from a jetty off the Australian Institute of Marine Science (19°17′ S; 147°03′ E) from 3 m water depth. The sediment was placed into a 100 l tank and suspended by agitation, and the coarser grain fraction was allowed to settle for 1 h. The fine particles, still in suspension after 1 h, were then collected by siphoning directly from the top of the tank, and allowed to settle for a further 3 h. This sediment was then passed through a 63 μm mesh, keeping only the <63 μm fraction.

The suspended sediment treatments consisted of filtered seawater, to which 0, 25, 50, 100, 200 and 400 mg dry weight (DW) l−1 of suspended sediment solution was added. Final amounts of suspended sediment were calculated by determining the DW of a known volume of the stock solution. Twenty-nine water chemical and geological parameters were analysed for each of the sediment types used; these and the methods used for determination are listed in Table 2.

Salinity

Salinity was manipulated by adding Super-Q water to filtered seawater, resulting in 36, 34, 32, 30 and 28 ppt salinity.

Dissolved inorganic nutrients

Two sources of dissolved inorganic nutrients were compared: a nitrate (potassium nitrate) and phosphate (dipotassium hydrogen phosphorus) treatment, and an ammonium (ammonium chloride) and phosphate (as above) treatment. Nutrients were added to filtered seawater at a nitrogen to phosphorus molar ratio of 5:1. The nutrient treatments consisted of a filtered seawater control and nominal concentrations of nitrate/phosphate and ammonium/phosphate of 1.25:0.25, 2.5:0.5, 5:1, 10:2 or 20:4 μM. Final concentrations of nutrients were confirmed as outlined in Table 2.

Experiment 2: interactions between suspended sediment, salinity and nutrients

The second experiment investigated interactions between the main effect treatments of Experiment 1. There were three nutrient treatments with nominal concentrations of 0:0, 5:1 and 10:2 μM nitrate and phosphate, three sediment treatments with nominal concentrations of 0, 50 and 100 mg DW l−1, and two salinity treatments (36 and 32 ppt). An extra replicate of each treatment was added to the experiment and filtered seawater added in place of eggs or sperm for later analysis of the various water quality parameters to confirm the nominal concentrations. A filtered seawater control and all possible interactions of the above treatments were investigated in five replicates of each. The experiment proceeded as described above.

Experiment 3: comparison of suspended sediment types

Five different types of sediments were collected 4 weeks prior to the spawning event. The upper 5 cm of sediment was collected from just below the water level at the estuarine shore of the Chester River (13°04′ S; 143°33′ E), a catchment in the far northern section of the GBR with minimal agriculture (Fabricius et al. 2005). The upper 5 cm of marine sediments was collected by SCUBA from 5 to 10 m depth from the leeward sides of the near-shore fringing reefs of High Island (17°10′ S, 146°00′ E), Wilkie Island (13°46′ S, 143°38′ E), and the lagoon of the offshore reef 14-077 (14°19′ S, 145°13′ E). The fifth sediment type was aragonite silt, a by-product of slicing coral skeletons of massive Porites sp. for growth band analyses (for details see Weber et al. 2006). All sediments were prepared as described above.

Treatments (each with five replicates) consisted of filtered seawater, with 0, 4, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256 and 512 mg DW l−1 suspended sediment solution from either one of the five stock solutions. A treatment with 1,024 mg DW l−1 was additionally tested, but samples were lost in two of the sediments; results of the successful treatments are included in the graphics but not in the statistical analyses. Sediment and water quality properties (29 parameters) were analysed as detailed in Table 2. To characterise the sediments, the sediment parameters were z-transformed, parameters were grouped into four categories, and z-transformed parameter values summed for each sediment type to form the following four indices: grain size (GSI), organic and nutrient related parameters (ONP), geochemical parameters (GCP), and dissolved nutrients (DNI). GSI was calculated as the sum of z-scores of the four parameters: mean grain size, and the 25, 50 and 75 percentiles of sediment volume. ONP was calculated as the sum of z-scores of the six parameters: chlorophyll a (Chl a) and phaeophytin (Phaeo) (an indicator of nutrient status; Brodie et al. 2007), ash-free dry weight (AFDW) (an indicator of organic matter), total organic carbon (TOC), total nitrogen (TN) and total phosphorous (TP). GCP was calculated as the sum of z-scores of fifteen metal and trace elements. DNI was calculated based on the six parameters: dissolved organic carbon (DOC), ammonium (NH4), nitrate (NO3), nitrite (NO2), silicate (Si) and phosphate (PO4).

Statistical analysis

Experiment 1

The data from the fertilisation and embryo development experiments were analysed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). One-factor ANOVAs were conducted to test the main effects of differing concentrations of suspended sediment and salinity, while a two-factor ANOVA was conducted to test for the effects of dissolved nutrients on fertilisation success and development of A. millepora embryos in isolation. Data were tested for deviation from homogeneity of variances and arcsine transformed where required. Post hoc comparisons of means for significant factors in the ANOVAs were done using Student-Newman Keuls (SNK) tests.

Experiment 2

To test for synergistic effects among the water quality parameters on the fertilisation success and development on A. millepora embryos, a three-factor ANOVA was used with suspended sediment (three levels), nutrients (three levels, fixed and orthogonal) and salinity (three levels, fixed and orthogonal) as the factors. Data were tested for deviation from homogeneity of variances and arcsine transformed where required.

Experiment 3

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for differences in fertilisation and early development abnormalities between sediment type and concentration. Data were tested for deviation from homogeneity of variances and arcsine transformed where required. A Spearman non-parametric rank correlation test was used to test the correlation of ranked rates of fertilisation with the four sediment indices for the five sediments. The AIMS jetty sediment was not included in this analysis as gametes were exposed to different treatment concentrations.

All results were given as the mean ± standard error, and as not all the data required transformation all plots are of untransformed data to maintain consistency. Data analyses were conducted with Statistica 6.0 (StatSoft) and the statistical software package R (R Development Core Team 2008).

Results

Experiment 1: response curves

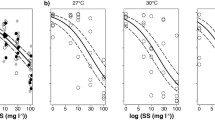

The responses of gametes exposed to increasing sediments and nutrients, and decreasing salinity are shown in Fig. 1 and Table 3. The controls were characterised by high levels of fertilisation (87.1 ± 2.2% SE) and moderate rates of developmental abnormalities (20.1 ± 1.6%). Sediment significantly affected rates of fertilisation yet had no effect on successful embryo development (Table 3; Fig. 1a, b). Fertilisation declined to 75.6 ± 5.4% at 100 mg l−1 suspended sediments, and 35.5 ± 4.8% at 200 mg l−1 (Fig. 1a). Fertilisation was not affected by 36–32 ppt salinity, while it dropped to 33.6 ± 4.6% at 30 ppt, and no fertilisation was observed at 28 ppt (Table 3; Fig. 1c). Salinity of 32 ppt led to an increase in developmental abnormality of ~10%, while salinity of 30 ppt resulted in 100% developmental abnormality (Fig. 1d). Neither the nitrate/phosphate nor the ammonium/phosphate treatments significantly affected fertilisation or development, even at the highest nutrient concentrations (Table 3; Fig. 1e, f).

Percentage of fertilisation and abnormal development in gametes of the coral Acropora millepora in response to exposure to various concentrations of suspended sediment (AIMS jetty), salinity and dissolved inorganic nutrients (Experiment 1). * Represents significant difference (P < 0.05; Table 3)

Experiment 2: interactions between suspended sediment, salinity and nutrients

Fertilisation rates of gametes exposed simultaneously to combinations of sediments, salinity and nutrients are shown in Fig. 2. There was a significant interactive effect between sediments, salinity and nutrients on fertilisation (Table 4). While in Experiment 1, fertilisation was not affected by sediments at ≤50 mg l−1, salinity at ≥32 ppt or any of the nutrient treatments (Fig. 1 a, c, e), fertilisation was significantly reduced at these levels and higher when in combination (Fig. 2). At the highest nutrient concentration of 10:2 μM NO3:PO4 and salinity of 32 ppt, fertilisation was reduced at 100 mg l−1 sediments compared with treatments with 0 and 50 mg l−1. At 36 ppt salinity, there was no sediment effect at 0 and 50 mg l−1 at the lowest two nutrient concentrations, though when nutrients were increased to 10:2 μM NO3:PO4 there was a significant effect at all sediment concentrations (Fig. 2c).

Percentage of fertilisation and abnormal development in gametes of the coral Acropora millepora in response to combined exposure to suspended sediment (AIMS jetty), salinity, and dissolved inorganic nutrients (Experiment 2). Line above bars represent that there is no significant difference between treatments, while * represents significant difference (P < 0.05; Table 4)

There were no interactive effects of salinity, sediment or nutrients on proportion of embryonic abnormalities.

Experiment 3: comparison of suspended sediment types

In the control treatments, the level of fertilisation averaged 71.0 ± 2.4%, and 24.5 ± 2.3% of embryos showed developmental abnormalities. Fertilisation was significantly reduced at the highest sediment levels for two of the five sediment types (Wilkie and High Islands; Fig. 3). Consequently, the analyses showed strong interactions between the effects of sediment type and sediment concentration on fertilisation success (Tables 5, 6).

Percentage of fertilisation in gametes of the coral Acropora millepora in response to exposure to five types of suspended sediments (Experiment 3). * Represents significant difference (P < 0.05; Table 5)

Levels of abnormal development averaged 34% over all treatments, and showed weak and complex interactions between sediment types and amount (Tables 5, 6). The highest level of abnormal development (45.1 ± 3.3%) was observed in embryos exposed to Chester River sediment at 16 mg DW l−1. The lowest levels of abnormalities were found for the lowest concentrations of Wilkie Island sediments (22.2% and 20.8%, respectively).

The concentrations and derived indices of each of the five sediments, and of the AIMS jetty sediment from Experiment 1, are listed in Table 7. Median grain sizes of the silt-sized sediments ranged from 11 to 23 μm, with smallest grain size in the AIMS jetty sediment (Experiment 1) or High Island (Experiment 3) and highest for aragonite silt. The organic and nutrient-related parameters (ONP) were highest for Chester River sediment, and lowest for aragonite silt. The geochemical parameters were highest in the AIMS jetty and High Island sediment, and lowest in aragonite silt. The index characterising dissolved inorganic nutrients was highest in the two inshore sediments Wilkie and High Island, and lowest in the AIMS jetty and Chester River sediments.

In order to investigate the role various sediment properties may play in determining their effects on coral reproduction, fertilisation rates exposed to 512 mg l−1 of the five sediment types were rank ordered (in increasing order) as follows: Wilkie Island sediments (49.9 ± 3.6%), followed by High Island sediment (58.2 ± 8.7%), offshore sediments (64.8 ± 1.0%), Chester River sediment (76.1 ± 3.5%) and aragonite silt (76.8 ± 4.3%). Chester River and aragonite silt were given the same rank order. The ranking of fertilisation rates was strongly related to the index characterising the dissolved nutrients in the sediment treatment (DNI, P = 0.005), with higher nutrient concentrations resulting in lower fertilisation rates (Table 8, Fig. 4). The apparent positive relationship of fertilisation rate to grain size was non-significant (GSD, P = 0.054). Fertilisation rates were also clearly unrelated to the geochemical and the organic and nutrient-related sediment parameters (P > 0.1).

Level of fertilisation in Acropora millepora (rank ordered) after exposure to five different sediment types characterised by indices for sediment grain size (GSI) and dissolved nutrients (DNI). The solid and dashed lines indicate the linear regression fit and 95% confidence intervals of the regression line, respectively

Discussion

This study investigated the interactive effects of suspended sediments, salinity and dissolved inorganic nutrients on fertilisation success and embryonic development in a scleractinian coral. The results from this experiment confirm previous studies that have shown that suspended sediments, salinity and nutrients at environmentally relevant levels (see Table 1) affect the reproductive successes in corals; it furthermore demonstrates that these effects are interactive. Suspended sediments with different organic, nutritive and geophysical properties also differed in their effects on fertilisation and embryonic development.

Increased suspended sediments in the water column negatively affect the physiology of corals, including their rates of photosynthesis, growth, survival and energy expenditure (see reviews by Rogers (1990) and Fabricius (2005)). While mean suspended sediment concentrations are typically <5 mg l−1 (Rogers 1990), they exceed ~80 mg l−1 for 20–30 days per year due to wind resuspension around some GBR inshore reefs (Wolanski 1994; Wolanski et al. 2005). Wolanski et al. (2008) measured suspended sediment levels of 280 mg l−1 as a result of a flood plume during calm weather, and 500 mg l−1 due to a combination of flood plume and resuspension during a storm event. Here, levels of suspended sediment ≥50 mg l−1 inhibited fertilisation yet had no effect on early development, a finding that closely matches that of Gilmour (1999) who found that suspended sediment ≥50 mg l−1 inhibited fertilisation yet had no effect on larval development. Interestingly, Gilmour (1999) found no difference in fertilisation between the 50 and 100 mg l−1 treatments, whereas in the present study there was a continued decline in the fertilisation with increasing concentrations of suspended sediments: fertilisation dropped from 92% at 50 mg l−1 to 75% at 100 mg l−1 and 35% at 200 mg l−1. Such differences are likely to be attributable to the different coral species or sediment types used. Gilmour (1999) used Acropora digitifera and sourced sediment from spoil dredged from a large port that comprised grain sizes of ~50–200 μm, while the present study used fresh (presumably biologically active) coastal marine sediments with <63 μm grain size.

The effect of differences in sediment properties on coral fertilisation and early development was further investigated by exposing the gametes to various types of sediments with contrasting properties including grain size, organic and nutrient related parameters, geochemical properties and dissolved nutrients. A reduction in fertilisation was only found in sediments containing high dissolved nutrients and small sediment grain sizes. The AIMS Jetty sediment used in Experiment 1 appeared to reduce fertilisation more than any of the sediments used in Experiment 3; however, results were not strictly comparable as different concentrations were used in the two studies. Nevertheless it is noteworthy that the AIMS Jetty sediment had the lowest GSI of all sediments, strengthening the evidence for a potential correlation between GSI and fertilisation.

The mechanisms by which coral fertilisation could be impaired by suspended sediments are presently unknown. It is possible that suspended sediments may act as physical barrier between sperm and egg: suspended sediment may hinder, damage or adhere to sperm affecting its viability and movement hence reducing the number of egg–sperm contacts, or sediment particles may cover the micropyle blocking access to the sperm (Galbraith et al. 2006). Gilmour (1999) observed greater aggregation of eggs in treatments exposed to suspended sediment and suggested that this may result in fewer contacts between sperm and egg. These suggestions may help to explain the role of sediment presence in reducing fertilisation success, yet they fail to account for the interactive effects of dissolved nutrients. A number of studies have shown that sediment microorganisms rapidly recycle coral spawning products (Wild et al. 2004), and that sediment properties, including particle size, are responsible for binding nutrients (Pailles and Moody 1992) and harbouring microorganisms (Crump and Baross 1996). We speculate that microbial communities attached to suspended sediment particles might be one of the mechanisms responsible for low fertilisation in sediment-exposed coral gametes; however, this hypothesis requires further study.

The correlation between sediment nutrients and fertilisation rate shown in Experiment 3 have to be interpreted with caution, as the number of sediment variables is high compared with the number of sediments investigated, and some of the sediment parameters are highly correlated with each other. Nevertheless, the results agree with the findings of Experiment 2, showing that interactions between high nutrient concentrations and sedimentation negatively affect coral fertilisation rates.

Salinity is an important environmental factor for corals, as corals lack mechanisms for osmoregulation (Muthiga and Szmant 1987). Some inshore coral reefs of the GBR are exposed to reduced salinity from flood plumes almost annually (Devlin et al. 2001), yet only a relatively small proportion of these floods coincide with spawning. Heavy localised monsoonal rainfall can also occur during the coral mass spawning period, resulting in the formation of low salinity surface water layers. Anecdotal evidence by Harrison et al. (1984) suggested that the entire reproductive output of a coral reef flat in the GBR was destroyed when the mass spawning event coincided with heavy rainfall destroying all coral propagules on the surface, most probably due to reduced salinity.

Effects of reduced salinity on adult corals are well documented in the literature (e.g. Moberg et al. 1997; Alutoin et al. 2001; Kerswell and Jones 2003). However; there are fewer studies on the effects of reduced salinity on reproductive processes including fertilisation and larval development. This study demonstrated a significant reduction in fertilisation in response to a reduction in salinity to 30 ppt, while at 28 ppt no fertilisation of coral eggs occurred. These results are similar to those of Richmond (1993) who found that the rate of fertilisation dropped from 88% to 25% with a drop in salinity from 34 to 28 ppt, and from 58% to 34% with a drop in salinity from 35 to 31.5 ppt in corals from Guam and Okinawa, respectively. The present study also showed increased levels of developmental abnormalities at 30 ppt salinity treatment compared to 32 or 35 ppt, again confirming previous studies which also recorded a reduction in embryo viability and planulae survival in response to reductions in salinity (Richmond 1993; Vermeij et al. 2006). Increasing rates of abnormal development, in addition to reduction in fertilisation levels, can bring about a marked reduction in viable larvae and may have a profound impact on recruitment (Bassim et al. 2002).

Nutrient concentrations vary widely around inshore coral reefs of the GBR, with lowest concentrations during the dry season and orders of magnitude greater values in flood plumes (Table 1). This study showed that dissolved inorganic nutrients on their own did not affect rates of fertilisation or early larval development in A. millepora. This result contrasts with Harrison and Ward (2001) who found that fertilisation rates and development in the sympatric species Acropora longicyathus were significantly affected by ammonium, phosphate and ammonium/phosphate at levels similar to those investigated in the present study. In Goniastrea aspera exposed to the same levels of nutrients, fertilisation rates were affected at the highest treatment (50 μM) of ammonium plus phosphate, and most treatments adversely affected larval development (Harrison and Ward 2001). The sensitivity of coral fertilisation experiments is known to strongly depend on sperm density and gamete viability (Oliver and Babcock 1992; Marshall 2006), and it is possible that differences in the viability of different crosses may explain the different outcomes between the two sets of experiments. Additionally, the differences may also have been due to species-specific differences in sensitivities to elevated nutrients, as reviewed by Koop et al. (2001). Cox and Ward (2002) also showed different effects of increased ammonia on the reproduction in a broadcasting coral, Montipora capitata, and a brooding coral, Pocillopora damicornis. Planulation in P. damicornis ceased after 4 months of exposure to ammonium, while in M. capitata there was no change in fecundity or fertilisation success.

This study showed that there was a significant synergistic interaction between salinity, sediment and nutrients on fertilisation rates of A. millepora. This finding highlights the complex nature of the effects of changing water quality on coral ecology. Nutrients and low concentrations of sediments on their own had no effect on fertilisation rates yet when occurring in combination there was a significant reduction in fertilisation. Similarly, while slightly reduced salinity on its own had no effect, fertilisation was reduced when water with slightly reduced salinity carried elevated levels of sediments or nutrients. This interaction is particularly relevant when considering the changed nature of flood plumes: nutrient and sediment loads carried in flood plume waters into the Great Barrier Reef have increased around fivefold since onset of western agriculture, due to soil erosion from overgrazing, and increasing fertiliser application (Devlin et al. 2001; Furnas 2003; McCulloch et al. 2003). Thus, while exposure to low amounts of sediment-poor freshwater seems to reduce fertilisation success only in a minor way, it constitutes a major problem for coral fertilisation if that freshwater carries enhanced levels of dissolved inorganic nutrients and sediments, as often found in flood plumes from agriculturally modified catchments. The GBR lagoon, which covers an area of 30,000 km2, currently receives on average 66 km3 of freshwater, 14 to 28 million tonnes of sediment, and 43,000 and 1,300 to 22,000 tonnes of nitrogen and phosphorus, respectively, from the land per year (Furnas 2003). A significant proportion of these nutrients are associated with particulate matter (Verstraeten and Poesen 2000; Vaze and Chiew 2004), increasing the potential of synergistic detrimental effects on coral reproduction and on the resilience of nearshore reefs.

The early life history stages of coral have been shown to be extremely sensitive to changes in water quality (Ward and Harrison 1997; Negri et al. 2005; Markey et al. 2007), particularly fertilisation (Harrison and Ward 2001; Reichelt-Brushett and Harrison 2005). The finding that environmentally realistic changes in suspended sediment, salinity and dissolved inorganic nutrients can have a negative impact on fertilisation, and to a lesser extent on development, is clearly a reason for concern. Coral reefs around the world are under increasing threat from overfishing (Jackson et al. 2001), urban development (Hughes and Connell 1999), and climate change (Hoegh-Guldberg 1999; Hughes et al. 2003). An important aspect of the ability of coral reefs to withstand these ongoing disturbances is successful reproduction and recruitment. If recruitment is a limiting event in the life history of corals, then any reduction in fertilisation levels and additional increases in embryonic abnormalities will have profound consequences for the ability of coral reefs to recover from disturbances. This study therefore again confirms that the prevention of terrestrial runoff of nutrients and sediments through sustainable land management is an important management tool for reef conservation.

References

Alutoin S, Boberg J, Nyström M, Tedengren M (2001) Effects of the multiple stressors copper and reduced salinity on the metabolism of the hermatypic coral Porites lutea. Mar Environ Res 52:289–299

Babcock RC, Heyward AJ (1986) Larval development of certain gamete-spawning scleractinian corals. Coral Reefs 5:111–116

Babcock RC, Bull GD, Harrison PL, Heyward AJ, Oliver JK, Wallace CC, Willis BL (1986) Synchronous spawnings of 105 scleractinian coral species on the Great Barrier Reef. Mar Biol 90:379–394

Ball EE, Hayward DC, Reece-Hoyes JS, Hislop NR, Samuel G, Saint R, Harrison PL, Miller DJ (2002) Coral development: from classical embryology to molecular control. Int J Dev Biol 46:671–678

Bassim KM, Sammarco PW (2003) Effects of temperature and ammonium on larval development and survivorship in a scleractinian coral (Diploria strigosa). Mar Biol 142:241–252

Bassim KM, Sammarco PW, Snell TL (2002) Effects of temperature on success of (self and non-self) fertilization and embryogenisis in Diploria strigosa (Cnidaria, Scleractinia). Mar Biol 140:479–488

Brodie J, De’ath G, Devlin M, Furnas M, Wright M (2007) Spatial and temporal patterns of near-surface chlorophyll a in the Great Barrier Reef. Mar Freshwt Res 58:342–353

Chao SY (1988) Wind-driven motion of estuarine plumes. J Phys Oceanogr 18:1144–1166

Cox EF, Ward S (2002) Impact of elevated ammonium on reproduction in two Hawaiian scleractinian corals with different life history patterns. Mar Poll Bull 44:1230–1235

Crump BC, Baross JA (1996) Particle-attached bacteria and heterotrophic plankton associated with the Columbia River estuarine turbidity maxima. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 138:265–273

Devlin MJ, Brodie J (2005) Terrestrial discharge into the Great Barrier Reef Lagoon: nutrient behaviour in coastal waters. Mar Pollut Bull 51:9–22

Devlin M, Waterhouse J, Taylor J, Brodie J (2001) Flood plumes in the Great Barrier Reef: spatial and temporal patterns in composition and distribution. Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, Research Publication No. 68, Townsville

Fabricius KE (2005) Effects of terrestrial runoff on the ecology of corals and coral reefs: review and synthesis. Mar Pollut Bull 50:125–146

Fabricius KE, De’ath G, McCook L, Turak E, Milliams DMcB (2005) Changes in algal, coral and fish assemblages along water quality gradients on the inshore Great Barrier Reef. Mar Pollut Bull 51:384–398

Furnas M (2003) Catchments and corals: Terrestrial runoff to the Great Barrier Reef. Australian Institute of Marine Science and CRC Reef Research Centre, Townsville

Furnas MJ, Mitchell AW (1999) Wintertime carbon and nitrogen fluxes on Australia’s Northwest Shelf. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 49:65–175

Furnas M, Mitchell AM, Skuza M (1995) Nitrogen and phosphorus budgets for the Central Great Barrier Reef Shelf. Great Barrier Reef Park Marine Authority, Research Publication No. 36, Townsville

Galbraith RV, MacIsaac EA, Macdonald JS, Farrell AP (2006) The effect of suspended sediment on fertilization success in sockeye (Oncorhynchus nerka) and coho (Orcorhynchus kisutch) salmon. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 63:2487–2494

Gilmour J (1999) Experimental investigation into the effects of suspended sediment on fertilisation, larval survival and settlement in a scleractinian coral. Mar Biol 135:451–462

Harrington L, Fabricius K, Eaglesham G, Negri A (2005) Synergistic effects of diuron and sedimentation on photosynthesis and survival of crustose coralline algae. Mar Pollut Bull 51:415–427

Harrison PL, Ward S (2001) Elevated levels of nitrogen and phosphorus reduce fertilisation success of gametes from scleractinian reef corals. Mar Biol 139:1057–1068

Harrison PL, Babcock RC, Bull GD, Oliver JK, Wallace CC, Willis BL (1984) Mass spawning in tropical reef corals. Science 223:1186–1188

Hayashibara T, Ohike S, Kakinuma Y (1997) Embryonic and larval development and planula metamorphosis of four gamete-spawning Acropora (Anthozoa, Scleractinia). Proc 8th Int Coral Reef Sym 2:1231–1236

Haynes D, Johnson JE (2000) Organochlorine, heavy metal and polyaromatic hydrocarbon pollutant concentrations in the Great Barrier Reef (Australia) environment: a review. Mar Pollut Bull 41:267–278

Haynes D, Michalek-Wagner K (2000) Water quality in the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area: past perspectives, current issues and new research directions. Mar Pollut Bull 41:428–434

Hoegh-Guldberg O (1999) Climate change, coral bleaching and the future of the world’s coral reefs. Mar Freshw Res 50:839–866

Hughes TP, Connell JH (1999) Multiple stressors on coral reefs: a long-term perspective. Limnol Oceanogr 44:932–940

Hughes TP, Baird AH, Bellwood DR, Card M, Connolly SR, Folke C, Grosberg R, Hoegh-Guldberg O, Jackson JBC, Kleypas J, Lough JM, Marshall P, Nystroem M, Palumbi SR, Pandolfi JM, Rosen B, Roughgarden J (2003) Climate change, human impacts, and the resilience of coral reefs. Science 301:929–933

Hutchings P, Haynes D (2005) Marine Pollution Bulletin special edition editorial. Mar Pollut Bull 51:1–2

Hutchings P, Haynes D, Goudkamp K, McCook L (2005) Catchment to reef: water quality issues in the Great Barrier Reef region - an overview of papers. Mar Pollut Bull 51:3–8

Jackson JBC, Kirby MX, Berger WH, Bjorndal KA, Botsford LW, Bourque BJ, Bradbury RH, Cooke R, Erlandson J, Estes JA, Hughes TP, Kidwell S, Lange CB, Warner RR (2001) Historical overfishing and the recent collapse of coastal ecosystems. Science 293:629–638

Kerswell AP, Jones RJ (2003) Effects of hypo-osmosis on the coral Stylophora pistillata: nature and cause of ‘low-salinity bleaching’. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 253:145–154

Koop K, Booth B, Broadbent A, Brodie J, Bucher D, Capone D, Coll J, Dennison W, Erdmann M, Harrison P, Hoegh-Guldberg O, Hutchings P, Jones GB, Larkum AWD, O’Neill J, Steven A, Tentori E, Ward S, Williamson J, Yellowlees D (2001) ENCORE: The effect of nutrient enrichmenton coral reefs. Synthesis of results and conclusions. Mar Poll Bull 42:91–120

Loring DH, Rantala RTT (1992) Manual for the geochemical analyses of marine sediments and suspended matter. Earth Sci Rev 32:235–283

Luick JL, Mason L, Hardy T, Furnas MJ (2007) Circulation in the Great Barrier Reef Lagoon using numerical tracers and in situ data. Cont Shelf Res 27:757–778

Markey KL, Baird AH, Humphrey C, Negri AP (2007) Insecticides and a fungicide affect multiple coral life stages. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 330:127–137

Marshall DJ (2006) Reliably estimating the effect of toxicants on fertilization success in marine broadcast spawners. Mar Pollut Bull 52:734–738

McCulloch M, Fallon S, Wyndham T, Hendy E, Lough J, Barnes D (2003) Coral records of increased sediment flux to the inner Great Barrier Reef since European settlement. Nature 421:727–730

Moberg F, Nyström M, Kautsky N, Tedengren M, Jarayabhand P (1997) Effects of reduced salinity on the rates of photosynthesis and respiration in the hermatypic corals Porites lutea and Pocillopora damicornis. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 157:53–59

Muthiga NA, Szmant AM (1987) The effects of salinity stress on the rates of aerobic respiration and photosynthesis in the hermatypic coral Siderastrea siderea. Biol Bull 173:539–551

Negri AP, Heyward AJ (2000) Inhibition of fertilization and larval metamorphosis of the coral Acropora millepora (Ehrenberg, 1834) by petroleum products. Mar Pollut Bull 41:420–427

Negri A, Vollhardt C, Humphrey C, Heyward A, Jones R, Eaglesham G, Fabricius K (2005) Effects of the herbicide diuron on the early life history stages of coral. Mar Pollut Bull 51:370–383

Neil DT, Orpin AR, Ridd PV, Yu B (2002) Sediment yield and impacts from river catchments to the Great Barrier Reef lagoon. Mar Freshw Res 53:733–752

Okubu N, Motokawa T (2007) Embryogenesis in the reef-building coral Acropora spp. Zool Sci 24:1169–1177

Oliver J, Babcock R (1992) Aspects of the fertilization ecology of broadcast spawning corals: sperm dilution effects and in situ measurements of fertilization. Biol Bull 183:409–417

Pailles C, Moody PW (1992) Phosphorus sorption-desorption by some sediments of the Johnstone Rivers catchment, northern Queensland. Aust J Mar Freshw Res 43:1535–1545

Parker JG (1983) A comparison of methods used for the measurement of organic matter in marine sediments. Chem Ecol 1:201–210

R Development Core Team (2008) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, URL http://www.R-project.org

Reichelt-Brushett AJ, Harrison PL (2005) The effect of selected trace metals on the fertilization success of several scleractinian coral species. Coral Reefs 24:524–534

Richmond RH (1993) Effects of coastal runoff on coral reproduction. In: Ginsburg RN (compiler) Proceedings of the colloquium on global aspects of coral reefs: health, hazards and history. Rosenthiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, University of Miami, Miami, pp 360–364

Ryle VD, Wellington J (1982) Reduction column for automated determination of nitrates. Analytical Laboratory Note No. 19. Australian Institute for Marine Science, Townsville

Ryle VD, Mueller HR, Gentien P (1981) Automated analysis of nutrients in tropical seawaters. AIMS Oceanography Series Technical Bulletin No. 3. Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville

Rogers CS (1990) Responses of coral reefs and reef organisms to sedimentation. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 62:185–202

Strickland JDH, Parsons TR (1972) A practical handbook of seawater analysis. Fisheries Research Board of Canada, Bulletin 167, Ottawa

Vaze J, Chiew HS (2004) Nutrient loads associated with different sediment sizes in urban stormwater and surface pollutants. J Environ Eng 130:391–396

Vermeij MJA, Fogarty ND, Miller MW (2006) Pelagic conditions affect larval behaviour, survival, and settlement patterns in the Caribbean coral Montastraea faveolata. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 310:119–128

Verstraeten G, Poesen J (2000) Assessments of sediment fixed nutrient export from small drainage basins in central Belgium using retention ponds. In: Stone M (ed) The role of erosion and sediment transport in nutrient and contaminant transfer. IHAS Publication No 263. IAHS Press, Wallingford, pp 243–249

Ward S, Harrison PL (1997) The effects of elevated nutrient levels on settlement of coral larvae during the ENCORE experiment, Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Proc 8th Int Coral Reef Symp 1:891–896

Ward S, Harrison PL (2000) Changes in gametogenesis and fecundity of acroporid corals that were exposed to elevated nitrogen and phosphorus during the ENCORE experiment. Exp Mar Biol Ecol 246:179–221

Weber M, Lott C, Fabricius KE (2006) Sedimentation stress in a scleractinian coral exposed to terrestrial and marine sediments with contrasting physical, organic and geochemical properties. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 336:18–32

Wild C, Tollrian R, Huettel M (2004) Rapid recycling of coral mass-spawning products in permeable reef sediments. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 271:159–166

Wolanski E (1994) Physical oceanographic processes of the Great Barrier Reef. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida

Wolanski E, Fabricius K, Spagnol S, Brinkman R (2005) Fine sediment budget on an inner-shelf coral-fringed island, Great Barrier Reef of Australia. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 65:153–158

Wolanski E, Fabricius KE, Cooper TF, Humphrey C (2008) Wet season sediment dynamics on the inner shelf of the Great Barrier Reef. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 77:755–762

Woolfe KJ, Michibayashi K (1995) “Basic” entropy grouping of laser-derived grain-size data: an example from the Great Barrier Reef. Comput Geosci 21:447–462

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Australian Institute of Marine Science, the Catchment-to-Reef Program of the Cooperative Research Centre of the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area, and the Marine and Tropical Sciences Research Facility (MTSRF), part of the Australian Government’s Commonwealth Environment Research Facilities programme. MW acknowledges the support through a PhD scholarship by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) and the Max-Planck-Society, Germany. The authors would like to thank Andrew Negri and three anonymous reviewers for constructive comments on this manuscript.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Environment Editor Professor Rob van Woesik

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Humphrey, C., Weber, M., Lott, C. et al. Effects of suspended sediments, dissolved inorganic nutrients and salinity on fertilisation and embryo development in the coral Acropora millepora (Ehrenberg, 1834). Coral Reefs 27, 837–850 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-008-0408-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-008-0408-1