Abstract

Purpose

To systematically evaluate the effects of virtual tube current reduction and sparse sampling on image quality and vertebral fracture diagnostics in multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT).

Materials and methods

In routine MDCT scans of 35 patients (80.0% females, 70.6 ± 14.2 years, 65.7% showing vertebral fractures), reduced radiation doses were retrospectively simulated by virtually lowering tube currents and applying sparse sampling, considering 50%, 25%, and 10% of the original tube current and projections, respectively. Two readers evaluated items of image quality and presence of vertebral fractures. Readout between the evaluations in the original images and those with virtually lowered tube currents or sparse sampling were compared.

Results

A significant difference was revealed between the evaluations of image quality between MDCT with virtually lowered tube current and sparse-sampled MDCT (p < 0.001). Sparse-sampled data with only 25% of original projections still showed good to very good overall image quality and contrast of vertebrae as well as minimal artifacts. There were no missed fractures in sparse-sampled MDCT with 50% reduction of projections, and clinically acceptable determination of fracture age was possible in MDCT with 75% reduction of projections, in contrast to MDCT with 50% or 75% virtual tube current reduction, respectively.

Conclusion

Sparse-sampled MDCT provides adequate image quality and diagnostic accuracy for vertebral fracture detection with 50% of original projections in contrast to corresponding MDCT with lowered tube current. Thus, sparse sampling is a promising technique for dose reductions in MDCT that could be introduced in future generations of scanners.

Key Points

• MDCT with a reduction of projection numbers of 50% still showed high diagnostic accuracy without any missed vertebral fractures.

• Clinically acceptable determination of vertebral fracture age was possible in MDCT with a reduction of projection numbers of 75%.

• With sparse sampling, higher reductions in radiation exposure can be achieved without compromised image or diagnostic quality in routine MDCT of the spine as compared to MDCT with reduced tube currents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Vertebral fractures are frequent in clinical routine and are primarily observed in the context of injuries or as major manifestations of osteoporosis, even in the absence of any obvious trauma [1,2,3]. Spine radiography is commonly applied for the detection of suspected vertebral fractures; however, it has been shown that computed tomography (CT) is superior by reducing the risk of missing a fracture, thus resulting in a higher sensitivity and specificity with fracture detection rates of 97 to 100% at the spine [4,5,6].

The increased use of CT instead of radiography for the purpose of improved diagnostics comes at the cost of elevated radiation exposure for the patient: one-time scanning with a modern CT scanner applies an estimated effective dose of 5.6 mSv and 10.0 mSv for the lumbar and whole dorsal spine, respectively [7, 8]. The use of CT entails an estimated cancer risk ratio that is multifold higher than in radiography, and it can further increase due to cumulative effects when additional imaging is performed [7,8,9]. Thus, CT with reduced radiation exposure, but without simultaneous constraints for image quality or diagnostic accuracy seems crucial.

Despite its clinical relevance, previous research on dose reductions in CT at the spine is generally scarce. In vivo, radiation exposure reductions have been achieved by lowered tube current or voltage at the level of the cervical spine, resulting in largely preserved image quality except for the lower cervical spine [10, 11]. Recently, iterative reconstruction (IR) algorithms have been applied together with low-dose CT, but led to worse image quality for soft tissue and cervical vertebrae when compared to standard-dose CT using filtered back projection (FBP) [12]. To date, only few studies investigated CT with reduced doses specifically for diagnostics of vertebral fractures, showing that low-dose CT with IR may maintain a high diagnostic performance compared to standard-dose CT with IR in trauma patients [13, 14].

In addition to lowering tube current or voltage to reduce x-ray exposure during CT, the number of acquired projections can be decreased with sparse-sampled acquisition schemes. Reducing projection views is a promising strategy since lowering the number of projections can clearly reduce the radiation dose, with previous research indicating a high potential of this approach resulting in reasonable image quality [15,16,17,18,19,20]. However, sparse sampling has not been applied at the spine for fracture diagnostics yet.

Against this background, the aim of this study is to evaluate the effects of virtual tube current reduction and sparse sampling on image quality and vertebral fracture diagnostics in multi-detector CT (MDCT). Our hypothesis is that MDCT with sparse sampling would provide better image and diagnostic quality when compared to MDCT with virtual lowering of tube current and, thus, might allow for more drastic reductions in radiation exposure.

Materials and methods

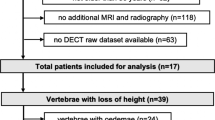

Patients

This retrospective study was approved by the local institutional review board (registration number: 62/18S) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Overall, 35 patients were included (80.0% females, mean age: 70.6 ± 14.2 years, age range: 26.2–93.1 years), with 23 patients (65.7%) showing at least one vertebral fracture (fracture group) and 12 patients (34.3%) showing no vertebral fracture (control group). Eligible patient cases were identified in the institutional digital Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS) between November 2016 and November 2017.

Inclusion criteria were (1) availability of routine MDCT of the spine (irrespective of the initial suspected diagnosis or distinct clinical symptoms leading to MDCT), (2) additional spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed prior or subsequent to MDCT (including short-tau inversion recovery sequences; only for the fracture group), and (3) diagnosis of at least one vertebral fracture according to MDCT (only for the fracture group). Exclusion criteria for both the fracture and control group were (1) age below 18 years, (2) movement artifacts in imaging data, (3) malignant bone lesions (e.g., bone metastases), (4) any history of metabolic bone disorders aside from osteoporosis, and (5) any implants captured by the field of view (FOV).

Multi-detector computed tomography

All scans were performed with a 64-channel MDCT scanner (Brilliance 64; Philips Healthcare). Parameters of the scanning protocol are shown in Table 1. X-ray tube current was modulated implicitly by the scanner during the helical scan according to the examined body part and estimated body size as derived from the scout scan. All examinations were performed without administration of a contrast agent.

Virtual tube current reduction and sparse sampling

Based on raw projection data, we used a simulation algorithm to generate lower tube currents for MDCT scans [16, 21,22,23]. System parameters of the scanner were considered and electronic noise was calibrated for each pixel at the detector. Simulations were generated as if the scans were made at 50% (D50 P100), 25% (D25 P100), and 10% (D10 P100) of the original x-ray tube current and used for image evaluation, in addition to the original imaging data defined as D100 P100. Furthermore, sparse sampling was applied at levels of 50% (D100 P50), 25% (D100 P25), and 10% (D100 P10) of the original projection data, which was achieved by reading every second, fourth, and tenth projection angle and deleting the remaining projections in the sinogram [16, 23, 24]. While the projection number per full rotation was lowered, other parameters, including patient location and projection geometry, were not changed. All images were reconstructed using FBP and a standard Ram-Lak filter [25, 26]. Table 1 provides an overview of image reconstruction parameters.

Image evaluation

Two board-certified radiologists (6 and 8 years of experience in radiology) evaluated all imaging data (35 patients × 7 imaging datasets per patient = 245 datasets for evaluation for reader 1 [R1] and reader 2 [R2], respectively), which were uploaded and stored in IntelliSpace Portal (version 9.0; Philips Healthcare) for visualization and evaluation.

First, both readers evaluated the original images with 100% tube current and projections (D100 P100) as the clinical standard in consensus with the MRI available to confirm the diagnosis of an acute or old vertebral fracture. Then, both readers independently evaluated the remaining datasets in random order (D50 P100, D25 P100, D10 P100, D100 P50, D100 P25, and D100 P10), assessing images derived from the same tube current or number of projections within 1 day for all patients and sticking to an interval of at least 7 days before continuing with images of another tube current or number of projections. The order of patient cases was also randomized for each tube current and number of projections, with the readers being blinded to all clinical patient data, the evaluations of each other, the assignments of patients to the fracture or control group, and all previous evaluations performed.

During evaluations, the number of vertebral fractures per patient had to be determined first, with the vertebrae included in the FOV being provided for each case to allow assignment of single fractures to specific vertebrae. Then, the items and scores presented in Table 2 were considered.

Statistical analyses

For statistical analyses and generation of graphs, SPSS (version 20.0; IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, IBM Corp.) was used. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Descriptive statistics were calculated for patient demographics and all items of evaluation. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were performed to compare overall image quality, overall artifacts, contrast of vertebrae, and diagnostic confidence between MDCT with virtually lowered tube current and sparse-sampled images, i.e., D50 P100 vs. D100 P50, D25 P100 vs. D100 P25, and D10 P100 vs. D100 P10, respectively. Furthermore, overall image quality, overall artifacts, and contrast of vertebrae of D100 P100 as the gold standard were compared with MDCT with virtually lowered tube current and sparse-sampled images using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, which were achieved separately for each reader.

Interreader intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were calculated for overall image quality, overall artifacts, contrast of vertebrae, and diagnostic confidence in MDCT with virtually lowered tube current and sparse sampling, respectively [27, 28]. As a measure of agreement between imaging with virtual lowering of tube current and sparse sampling, Cohen’s kappa coefficients were determined for age of fracture. Moreover, weighted Cohen's kappa coefficients were determined between the results of both readers for age of fracture [29,30,31].

Results

Virtual lowering of tube current and sparse sampling were successfully achieved in all patients (Figs. 1 and 2). A median of eight vertebrae (range 4–19 vertebrae) was captured by the FOV of MDCT scans, which covered the cervical spine in 20.0%, the cervico-thoracic spine in 8.6%, the thoracic spine in 5.7%, the thoraco-lumbar spine in 28.6%, and the lumbar spine in 37.1%. The average volumetric CT dose index recorded in the dose reports was 11.7 ± 5.7 mGy for original MDCT scans (Table 1), and was amounted 5.9 mGy, 2.9 mGy, and 1.2 mGy for MDCT with virtually lowered tube current or sparse sampling at 50%, 25%, and 10% of original data, respectively.

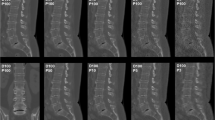

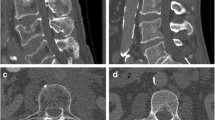

Virtual tube current reduction and sparse sampling in multi-detector CT (MDCT) of the cervical spine. Sagittal slices derived from full-dose MDCT (D100 P100), MDCT with virtually lowered tube current (D50 P100, D25 P100, and D10 P100), and MDCT with sparse sampling (D100 P50, D100 P25, and D100 P10) are shown in a patient with a cervical fracture (C2, dens fracture)

Virtual tube current reduction and sparse sampling in multi-detector CT (MDCT) of the thoracic and lumbar spine. Sagittal slices derived from full-dose MDCT (D100 P100), MDCT with virtually lowered tube current (D50 P100, D25 P100, and D10 P100), and MDCT with sparse sampling (D100 P50, D100 P25, and D100 P10) are shown in a patient with five thoracic fractures (T3, T6, T8, T10, and T11)

Both readers correctly identified all patients of the control group (34.3% of included patients) without any assignments of vertebral fractures to controls in MDCT with virtually lowered tube current or sparse sampling. Among patients of the fracture group (65.7% of included patients), a total of 48 vertebral fractures was observed in the original MDCT with 100% tube current and projections (D100 P100). Patients of the fracture group showed a median of two vertebral fractures (range 1–6 vertebral fractures). These fractures affected the cervical spine in 10.0%, the thoracic spine in 40.0%, and the lumbar spine in 50.0%. Based on original MDCT and MRI scanning, vertebral fractures were diagnosed as acute in 58.3% and old in 41.7%.

Overall image evaluation

Both virtual tube current reduction and sparse sampling led to decreased overall image quality, increased overall artifacts, and reduced contrast of vertebrae according to the evaluation of both readers (Table 3, Figs. 1 and 2, Supplementary Fig. 1). The assessed parameters were significantly different in MDCT with virtually lowered tube current and sparse-sampled datasets as compared to those in D100 P100 (p < 0.001; D100 P100 vs. D50 P100/D25 P100/D10 P100 and D100 P100 vs. D100 P50/D100 P25/D100 P10 of both readers).

When comparing MDCT with virtually lowered tube current to sparse-sampled datasets for overall image quality, sparse sampling resulted in significantly better scores according to each reader for all comparisons (p < 0.001, D50 P100 vs. D100 P50, D25 P100 vs. D100 P25, and D10 P100 vs. D100 P10 of both readers; Table 3 and Fig. 3). Similar findings with better scores for sparse-sampled imaging than for MDCT with virtually lowered tube current were observed for overall artifacts (p < 0.001, except for D50 P100 vs. D100 P50 for R2: p = 0.20; Table 3 and Fig. 3) and contrast of vertebrae (p < 0.001, except for D25 P100 vs. D100 P25 for R2: p = 0.005; Table 3 and Fig. 3). Good interreader agreement was observed for overall image quality, overall artifacts, and contrast of vertebrae, respectively (ICC > 0.80, R1 vs. R2 for D50 P100/D25 P100/D10 P100 and D100 P50/D100 P25/D100 P10; Table 3).

Overall image evaluation. This figure depicts the mean scores ± standard deviation for overall image quality, overall artifacts, and contrast of vertebrae according to the evaluation of reader 1 (R1) and reader 2 (R2). Blank circles show results for multi-detector CT (MDCT) with virtually lowered tube current (D50 P100, D25 P100, and D10 P100), whereas black circles visualize the results derived from sparse-sampled MDCT (D100 P50, D100 P25, and D100 P10). The black square represents the results for original MDCT with 100% of tube current and 100% of projections (D100 P100)

Fracture evaluation

Virtual tube current reduction by 50% of original current (D50 P100) allowed for correct detection of 100% (R1) and 95.8% (R2) of vertebral fractures when compared to original MDCT. Further lowering to 10% of original current (D10 P100) resulted in correct detection of 79.2% (R1) and 87.5% (R2) of vertebral fractures (Table 4). Sparse-sampled MDCT with 50% of the original projections (D100 P50) allowed for correct detection of all vertebral fractures by both readers as compared to original MDCT. Further decreasing the number of projections down to 10% of the original data allowed for correct detection of 95.8% (R1) and 91.7% (R2) of vertebral fractures (Table 4).

Both readers reported preserved high diagnostic confidence for both virtual lowering of tube current and lowered projection numbers down to 50% of original MDCT without a significant difference in scores (p = 0.48 for R1 and p = 0.41 for R2; Table 4 and Fig. 4). For MDCT with 25% or 10% of original projections, average diagnostic confidence was still high (D100 P25) to medium (D100 P10), and it was medium (D25 P100) to low (D10 P100) when MDCT with virtually lowered tube current was considered (Table 4 and Fig. 4). Correspondingly, a significant difference was observed between MDCT with virtually lowered tube current and sparse-sampled imaging at 25% or 10% of original tube current or projections (p < 0.001 for both readers; Table 4 and Fig. 4). Excellent agreement between the evaluations of both readers was observed for both virtual tube current reductions and sparse sampling down to 10% of projections of original imaging data (ICC > 0.90, R1 vs. R2 for D50 P100/D25 P100/D10 P100 and D100 P50/D100 P25/D100 P10; Table 4).

Diagnostic confidence. This figure depicts the mean scores ± standard deviation for diagnostic confidence according to the evaluation of reader 1 (R1) and reader 2 (R2). Blank circles show results for multi-detector CT (MDCT) with virtually lowered tube current (D50 P100, D25 P100, and D10 P100), whereas black circles visualize the results derived from sparse-sampled MDCT (D100 P50, D100 P25, and D100 P10)

Concerning the age of reported vertebral fractures, sparse sampling showed better results regarding the differentiation between acute, old, and unclear fracture age (Table 4). For sparse-sampled MDCT at 25% of original projections, fracture age was determined as unclear in 4.3% (R1) and 6.7% (R2) of detected vertebral fractures. According to imaging with 25% of original tube current, 42.6% (R1) and 48.9% (R2) of detected vertebral fractures were of unclear age (Table 4). Excellent agreement was observed in the evaluations of fracture age between readers (kappa > 0.88; Table 4).

Discussion

This study investigated the effects of virtual tube current reduction and sparse sampling on image quality and diagnostic accuracy of vertebral fractures in MDCT. When comparing virtual tube current reductions to sparse sampling, superior results for image quality and fracture diagnostics were evident for sparse-sampled MDCT. Specifically, no missed vertebral fractures occurred for MDCT with a reduction of 50% in projection numbers, and determination of fracture age was still reliably possible in MDCT with a reduction in projection numbers of 75%.

CT is increasingly applied for first-line diagnostics of vertebral fractures due to its high sensitivity and specificity and excellent fracture detection rates [4,5,6]. However, clearly higher estimated effective doses of 5.6 mSv for the lumbar and 10.0 mSv for the whole dorsal spine in CT compared with radiography result in a considerably increased risk of developing cancer later in life [7,8,9]. Importantly, cancer risks are summative, and radiography or CT performed for initial diagnostics are not the only sources of radiation exposure, with a patient suffering from an acute traumatic vertebral fracture being exposed to a cumulative effective dose of about 38 mSv only during inpatient stay and without taking into account later follow-up imaging [32]. Consequently, reduction of CT-related radiation exposure is necessary, but should ideally be achieved without loss of image quality or diagnostic accuracy. Despite evident clinical relevance, only a limited body of literature distinctly evaluated approaches for radiation exposure reductions in CT of the spine.

Concerning CT with reduced doses, a small increase in image noise and no difference in subjective image quality evaluation was reported for cervical structures, allowing dose reductions of 61–71% [11]. Low-kV CT with reduced radiation doses by approximately 34% demonstrated good image quality for structures of the neck, but compromised image quality for the lower cervical spine [10]. In patients with lumbar disc herniation, simulated low-dose CT with reductions in tube charge settings to 65% of the standard dose were considered adequate for diagnostic purposes previously [33]. Furthermore, IR algorithms have been introduced for CT with reduced doses, leading to better image quality for intervertebral discs, neural foramina, and ligaments, but worse image quality for vertebrae when compared with standard-dose CT using FBP [12]. Ultra-low-dose CT may still provide an acceptable image quality and exhibited a diagnostic accuracy similar to that of low-dose CT in patients with chronic lumbar back pain [34].

To the authors’ knowledge, only few recent studies investigated CT with reduced doses specifically for diagnostics of vertebral fractures. The diagnostic performance of lumbar low-dose CT (47–69% radiation dose reduction) combined with IR was comparable to that of standard-dose CT with IR [13]. Higher levels of IR for low-dose CT (50% radiation dose reduction) still provided high image quality and diagnostic confidence [14]. In contrast to these studies, we simulated tube current reduction, which allows for intra-subject comparisons between standard- and low-dose MDCT with virtually lowered tube currents down to even 10% of original imaging. Thus, low-dose MDCT was simulated with relative dose reduction steps in comparison to original MDCT, which enables systematic virtual tube current reductions as a fraction of the initially performed, optimal scanning protocol according to the scanner’s automatic tube current modulation.

We further applied sparse sampling, which is novel for diagnostics of vertebral fractures. So far, assessments of bone mineral density and microstructure at the spine derived from MDCT with sparse sampling have been performed, with sparse-sampled imaging appearing more robust in comparison to MDCT with virtually lowered tube currents [16, 17]. In the present study, sparse sampling was superior in terms of overall image quality, overall artifacts, and contrast of vertebrae when compared with MDCT with virtually lowered tube current (Table 3 and Fig. 3). These results were obtained with good to excellent correlations between two experienced readers for MDCT with virtually lowered tube currents and sparse sampling, respectively (Table 3 and Fig. 3). Furthermore, sparse sampling led to superior results in detecting vertebral fractures, with no missed fractures for D100 P50 in contrast to D50 P100 (Table 4). Diagnostic confidence and correct determination of fracture age was better for sparse sampling, with clinically acceptable determination of fracture age in D100 P25 compared with D25 P100 (Table 4 and Fig. 4).

There are limitations to this study. First, it is not yet possible to apply sparse sampling at commercial MDCT scanners, thus restricting direct clinical applicability. However, first results from a prototype were recently reported, indicating that sparse sampling for MDCT could become broadly available in future generations of MDCT scanners [19, 20]. Second, we used FBP instead of IR, but IR has the potential to provide increased image quality particularly for imaging with reduced doses [35,36,37]. The use of algorithms taking advantage of artificial intelligence for image reconstructions might further regularly improve image quality in the near future [37]. Third, we solely enrolled patients with vertebral fractures and without implants, such as spinal instrumentation. Thus, upcoming studies may evaluate sparse sampling in cohorts with spinal implants to distinctly evaluate whether sparse sampling is also beneficial and even superior to tube current restrictions when implant-related metal artifacts are present in MDCT. Fourth, the retrospective design and the comparatively small patient cohort have to be acknowledged as a limitation. Prospective approaches including more patients are needed to confirm the results of the present study.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate the feasibility of using sparse sampling for fracture detection at the spine, with clear superiority as compared to MDCT with virtual reduction of tube current. Therefore, sparse sampling represents a promising option that might allow for even more drastic radiation dose reductions while revealing better image quality and diagnostic characteristics than MDCT with tube current reduction does.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- FBP:

-

Filtered back projection

- FOV:

-

Field of view

- ICC:

-

Intraclass correlation coefficient

- IR:

-

Iterative reconstruction

- MDCT:

-

Multi-detector computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PACS:

-

Picture Archiving and Communication System

- R1:

-

Reader 1

- R2:

-

Reader 2

References

Cooper C, Atkinson EJ, O'Fallon WM, Melton LJ 3rd (1992) Incidence of clinically diagnosed vertebral fractures: a population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota, 1985-1989. J Bone Miner Res 7:221–227

Schousboe JT (2016) Epidemiology of vertebral fractures. J Clin Densitom 19:8–22

Van der Klift M, De Laet CE, McCloskey EV, Hofman A, Pols HA (2002) The incidence of vertebral fractures in men and women: the Rotterdam Study. J Bone Miner Res 17:1051–1056

Venkatesan M, Fong A, Sell PJ (2012) CT scanning reduces the risk of missing a fracture of the thoracolumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg Br 94:1097–1100

Harris TJ, Blackmore CC, Mirza SK, Jurkovich GJ (2008) Clearing the cervical spine in obtunded patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 33:1547–1553

Shah LM, Ross JS (2016) Imaging of spine trauma. Neurosurgery 79:626–642

Richards PJ, George J, Metelko M, Brown M (2010) Spine computed tomography doses and cancer induction. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 35:430–433

Richards PJ, George J (2010) Diagnostic CT radiation and cancer induction. Skeletal Radiol 39:421–424

Brenner DJ, Hall EJ (2007) Computed tomography--an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med 357:2277–2284

Gnannt R, Winklehner A, Goetti R, Schmidt B, Kollias S, Alkadhi H (2012) Low kilovoltage CT of the neck with 70 kVp: comparison with a standard protocol. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 33:1014–1019

Mulkens TH, Marchal P, Daineffe S et al (2007) Comparison of low-dose with standard-dose multidetector CT in cervical spine trauma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 28:1444–1450

Becce F, Ben Salah Y, Verdun FR et al (2013) Computed tomography of the cervical spine: comparison of image quality between a standard-dose and a low-dose protocol using filtered back-projection and iterative reconstruction. Skeletal Radiol 42:937–945

Lee SH, Yun SJ, Kim DH, Jo HH, Song JG, Park YS (2017) Diagnostic usefulness of low-dose lumbar multi-detector CT with iterative reconstruction in trauma patients: a comparison with standard-dose CT. Br J Radiol 90:20170181

Weinrich JM, Well L, Regier M et al (2018) MDCT in suspected lumbar spine fracture: comparison of standard and reduced dose settings using iterative reconstruction. Clin Radiol 73:675 e679–675 e615

Abbas S, Lee T, Shin S, Lee R, Cho S (2013) Effects of sparse sampling schemes on image quality in low-dose CT. Med Phys 40:111915

Mei K, Kopp FK, Bippus R et al (2017) Is multidetector CT-based bone mineral density and quantitative bone microstructure assessment at the spine still feasible using ultra-low tube current and sparse sampling? Eur Radiol 27:5261–5271

Mookiah MRK, Subburaj K, Mei K et al (2018) Multidetector computed tomography imaging: effect of sparse sampling and iterative reconstruction on trabecular bone microstructure. J Comput Assist Tomogr 42:441–447

Koesters T, Knoll F, Sodickson A, Sodickson DK, Otazo R (2017) SparseCT: interrupted-beam acquisition and sparse reconstruction for radiation dose reduction. Proc. SPIE 10132, Medical Imaging 2017: Physics of Medical Imaging, 101320Q. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2255522

Chen B, Muckley M, Sodickson A et al (2018) First multislit collimator prototype for sparseCT: design, manufacturing and initial validation The Fifth International Conference on Image Formation in X-Ray Computed Tomography, Salt Lake City, pp 52–55

Muckley M, Chen B, O’Donnell T et al (2018) Reconstruction of reduced-dose sparseCT data acquired with an interruped-beam prototype On A clinical scanner The Fifth International Conference on Image Formation in X-Ray Computed Tomography, Salt Lake City, pp 56-59

Zabic S, Wang Q, Morton T, Brown KM (2013) A low dose simulation tool for CT systems with energy integrating detectors. Med Phys 40:031102

Muenzel D, Koehler T, Brown K et al (2014) Validation of a low dose simulation technique for computed tomography images. PLoS One 9:e107843

Sollmann N, Mei K, Schwaiger BJ et al (2018) Effects of virtual tube current reduction and sparse sampling on MDCT-based femoral BMD measurements. Osteoporos Int. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-018-4675-6

Zhao Z, Gang GJ, Siewerdsen JH (2014) Noise, sampling, and the number of projections in cone-beam CT with a flat-panel detector. Med Phys 41:061909

Ramachandran GN, Lakshminarayanan AV (1971) Three-dimensional reconstruction from radiographs and electron micrographs: application of convolutions instead of Fourier transforms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 68:2236–2240

Fehringer A, Lasser T, Zanette I, Noel PB, Pfeiffer F (2014) A versatile tomographic forward- and back-projection approach on multi-GPUs. Proc. SPIE 9034, Medical Imaging 2014: Image Processing, 90344F. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2043860

Shrout PE, Fleiss JL (1979) Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 86:420–428

Bartko JJ (1966) The intraclass correlation coefficient as a measure of reliability. Psychol Rep 19:3–11

Cohen J (1968) Weighted kappa: nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol Bull 70:213–220

Cohen J (1960) A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas 20:37–46

Sim J, Wright CC (2005) The kappa statistic in reliability studies: use, interpretation, and sample size requirements. Phys Ther 85:257–268

Martin E, Prasarn M, Coyne E et al (2013) Inpatient radiation exposure in patients with spinal trauma. J Spinal Cord Med 36:112–117

Bohy P, de Maertelaer V, Roquigny A, Keyzer C, Tack D, Gevenois PA (2007) Multidetector CT in patients suspected of having lumbar disk herniation: comparison of standard-dose and simulated low-dose techniques. Radiology 244:524–531

Lee SH, Yun SJ, Jo HH, Kim DH, Song JG, Park YS (2018) Diagnostic accuracy of low-dose versus ultra-low-dose CT for lumbar disc disease and facet joint osteoarthritis in patients with low back pain with MRI correlation. Skeletal Radiol 47:491–504

Beister M, Kolditz D, Kalender WA (2012) Iterative reconstruction methods in X-ray CT. Phys Med 28:94–108

Willemink MJ, Leiner T, de Jong PA et al (2013) Iterative reconstruction techniques for computed tomography part 2: initial results in dose reduction and image quality. Eur Radiol 23:1632–1642

Willemink MJ, Noel PB (2018) The evolution of image reconstruction for CT-from filtered back projection to artificial intelligence. Eur Radiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-018-5810-7

Funding

This study has received support from Philips Healthcare and funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 637164—iBack—ERC-2014-STG) and the Nivida Corporation. We further acknowledge support through the German Department of Education and Research (BMBF) under grant IMEDO (13GW0072C) and the German Research Foundation (DFG) within the Research Training Group GRK 2274.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Guarantor

The scientific guarantor of this publication is Thomas Baum, MD.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript declare no relationships with any companies, whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article.

Statistics and biometry

One of the authors has significant statistical expertise.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was not required for this study because of its retrospective character and the analyses being based only on data acquired for clinical routine.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained.

Methodology

• Retrospective

• Diagnostic or prognostic study

• Performed at one institution

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 3036 kb)

Rights and permissions

OpenAccess This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Sollmann, N., Mei, K., Hedderich, D.M. et al. Multi-detector CT imaging: impact of virtual tube current reduction and sparse sampling on detection of vertebral fractures. Eur Radiol 29, 3606–3616 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-019-06090-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-019-06090-2