Abstract

Objectives

Investigate the effect of a novel Bayesian penalised likelihood (BPL) reconstruction algorithm on analysis of pulmonary nodules examined with 18F-FDG PET/CT, and to determine its effect on small, sub-10-mm nodules.

Methods

18F-FDG PET/CTs performed for nodule evaluation in 104 patients (121 nodules) were retrospectively reconstructed using the new algorithm, and compared to time-of-flight ordered subset expectation maximisation (OSEM) reconstruction. Nodule and background parameters were analysed semi-quantitatively and visually.

Results

BPL compared to OSEM resulted in statistically significant increases in nodule SUVmax (mean 5.3 to 8.1, p < 0.00001), signal-to-background (mean 3.6 to 5.3, p < 0.00001) and signal-to-noise (mean 24 to 41, p < 0.00001). Mean percentage increase in SUVmax (%ΔSUVmax) was significantly higher in nodules ≤10 mm (n = 31, mean 73 %) compared to >10 mm (n = 90, mean 42 %) (p = 0.025). Increase in signal-to-noise was higher in nodules ≤10 mm (224 %, mean 12 to 27) compared to >10 mm (165 %, mean 28 to 46). When applying optimum SUVmax thresholds for detecting malignancy, the sensitivity and accuracy increased using BPL, with the greatest improvements in nodules ≤10 mm.

Conclusion

BPL results in a significant increase in signal-to-background and signal-to-noise compared to OSEM. When semi-quantitative analyses to diagnose malignancy are applied, higher SUVmax thresholds may be warranted owing to the SUVmax increase compared to OSEM.

Key Points

• Novel Bayesian penalised likelihood PET reconstruction was applied for lung nodule evaluation.

• This was compared to current standard of care OSEM reconstruction.

• The novel reconstruction generated significant increases in lung nodule signal-to-background and signal-to-noise.

• These increases were highest in small, sub-10-mm pulmonary nodules.

• Higher SUV max thresholds may be warranted when using semi-quantitative analyses to diagnose malignancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

18F-FDG PET/CT is now commonly performed in the assessment of potentially malignant solitary pulmonary nodules [1, 2], but its use is limited in the evaluation of small pulmonary nodules [3, 4], with a paucity of studies evaluating its value in small, sub-10-mm pulmonary nodules [1, 4].

The use of semi-quantitative measurements in the evaluation of small pulmonary nodules is also uncertain, with no agreed standardised uptake value (SUVmax) threshold for differentiating benign from malignant aetiologies [1, 5–7]. Signal acquisition and technical factors such as the image reconstruction methodologies used have a greater impact on the accuracy of SUV measurements in small nodules compared to large nodules [8, 9].

There are two main types of PET reconstruction available: analytical and iterative. Generally iterative methods are more commonly used because of their improved signal-to-noise ratios compared to analytical algorithms, such as filtered back projection (FBP) [8–10]. Iterative methods also allow the modelling of various system factors that can be included in the reconstruction, such as the point spread function (PSF) [11–13]. The main iterative algorithm used is ordered subset expectation maximisation (OSEM) [14] which aims to find the most likely image from the raw data through repeated iterations of possibilities. Each iteration gives an image with a greater likelihood of describing the measured data. The main disadvantage of iterative algorithms is that it is not possible to run them to full convergence as the image noise increases with each iteration, becoming unacceptable before full convergence is reached [8, 10]. In general, OSEM is stopped after a predetermined number of iterations resulting in an underconverged image. The failure to accurately attribute the signal results in an underestimation of SUVs, and has the greatest effect in small FDG-avid foci such as sub-10-mm nodules.

Recently a new iterative PET reconstruction algorithm, Bayesian penalised likelihood (BPL), has been developed by GE Healthcare, called Q.Clear (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, USA) and includes PSF modelling [15]. Whilst penalised likelihood algorithms were first reported in 1987 [16], and their advantage over FBP was described in 1996 [17], their clinical use has so far been very limited. The BPL considered here includes a relative difference penalty, first introduced in 2002 [18]. The main advantage this has over other possible penalties is that it is a function of the difference between neighbouring voxels as well as a function of their sum [19]. This penalty function acts as a noise suppression term, which allows an increased number of iterations without the noise usually seen in OSEM [15]. The strength of this penalty function is controlled by the penalisation factor (beta), which is the only user-input variable to the algorithm. Modified block sequential regularized expectation maximization (BSREM) is used as an optimiser for this BPL algorithm, which, as a result of the penalty function, allows effective convergence to be achieved in images, potentially providing a more accurate SUV [19, 20].

The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of the iterative reconstruction technique using BPL on the analysis of nodules scanned with PET/CT, and to determine its effect on small, sub-10-mm nodules.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

All patients who underwent 18F-FDG PET/CT at our institution between November 2010 and December 2013 for the evaluation of pulmonary nodules, with subsequent histological diagnosis, were retrospectively identified. Nodules were defined as having a long-axis diameter of ≤30 mm on lung windows. Informed consent is not required for retrospective reviews of this nature in our institution.

18F-FDG PET/CT imaging protocol

PET/CT examinations were performed on a 3D mode time of flight (ToF) GE Discovery 690 PET/CT system (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, USA). The patients fasted for at least 6 h prior to their scan. Their blood glucose was measured prior to intravenous injection, with 4 MBq/kg of 18F-FDG. Imaging commenced 90 min post-injection (93 ± 7 min) and covered the skull base to upper thighs. The PET/CT images were acquired under normal tidal respiration for 4 min per bed position. The CT was performed using a pitch of 0.984, 120 kV, automA with a noise index of 25.

PET reconstructions

PET images were reconstructed using two different algorithms both of which used the CT for attenuation correction and the same normalisation correction factors. The standard of care PET reconstruction algorithm used is ToF OSEM (VPFX, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, USA). This was used with two iterations, 24 subsets and 6.4 mm Gaussian filter in our institution. The sinograms generated at the time of scanning were retrospectively processed using the new ToF BPL reconstruction algorithm (Q.Clear, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, USA) using a penalisation factor (beta) of 400, the only user-input variable for this algorithm.

Imaging analysis

Semi-quantitative analysis

The pre-existing PET images (reconstructed using OSEM) and new PET images reconstructed using BPL were fused with the CT component of the original study for analysis. The SUVmax of each nodule was recorded using a standard volume of interest (VOI) tool. Background SUVs were measured in the right lobe of liver and descending aorta at the level of the carina, with 3.0-cm and 1.0-cm diameter spherical VOIs, respectively. SUVmax, SUVmean and standard deviation within the VOI were recorded for both reference organs. Signal-to-background ratio (SBR) for each nodule was calculated as nodule SUVmax divided by descending aorta SUVmean. Nodule signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) was defined as nodule SUVmax divided by liver SUVsd using the standard deviation on a liver reference VOI (SUVsd) as the measure of noise. To identify possible change in image noise the background SNR was calculated as liver SUVmean divided by liver SUVsd.

Visual analysis

Visual analysis of the OSEM and BPL PET/CT images was performed by a radiology resident with 4 years of radiology (including 1 year of PET/CT) experience. Nodules were scored according to degree of FDG uptake (above-background, at-background or below-background). The reference organ for background uptake was the descending aorta. The scorer reviewed the cases in a randomised and unpaired order, blinded to the clinical details.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0 (IBM Corporation, New York, USA). P values ≤0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Background analysis

This was performed across the entire cohort. Differences in background SUVmean, SUVmax and SNR across the entire cohort were analysed using paired t tests.

Nodule analysis

Nodules were classified according to three different categories for analysis:

-

1.

Size: ≤10 mm or >10 mm in long-axis diameter on lung windows

-

2.

FDG uptake: FDG-positive (above-background) or FDG-negative (at/below-background). Background uptake was patient-specific and set as the descending aorta SUVmean on the OSEM algorithm.

-

a.

A sub-analysis of FDG-positive nodules was performed according to size

-

3.

Aetiology

For the first two categories, differences in nodule SUVmax, SBR and SNR were analysed using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. The percentage difference in nodule SUVmax (%ΔSUVmax) was also calculated. Differences in %ΔSUVmax within each category were analysed using the Mann–Whitney U test.

Across the entire cohort, and within the FDG uptake classification, correlation between %ΔSUVmax and nodule size was analysed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

Within the aetiological classification, differences in %ΔSUVmax and nodule size were analysed according to three categories: primary lung cancer, metastases and benign aetiologies, using the Kruskal–Wallis test.

Diagnostic performance

The performance of both algorithms to detect malignant nodules (primary lung cancer and metastases) was assessed using both semi-quantitative and visual criteria. For semi-quantitative criteria, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted, and area under the curve (AUC) values calculated. The areas under both ROC curves were compared using the method described by Hanley and McNeil [21]. The optimal SUV threshold for the diagnosis of malignancy was defined as the point on the curve closest to the upper left corner of the ROC space. Sensitivity, specificity and accuracy for malignancy detection were calculated for these thresholds. For visual criteria, nodules scored as above-background were designated malignant and nodules at-background or below-background were designated benign. Sensitivity, specificity and accuracy for malignancy detection were then calculated.

Results

Clinical characteristics

One hundred and four patients (45 male, 59 female, mean age 68 years, range 23–89 years) met the inclusion criteria. A total of 121 nodules were included for analysis, comprising various malignant (n = 106) and benign (n = 15) aetiologies. Malignant nodules comprised of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (n = 64), metastases of extra-thoracic malignancy (n = 32) and carcinoid (n = 10). Benign aetiologies included hamartoma, sarcoidosis and mycobacterial granulomata, benign alveolar adenoma and inflammatory scar. The mean nodule diameter was 15 mm (range 3–28 mm) with 31 nodules ≤10 mm and 90 nodules >10 mm.

Background analysis

Differences in all the background SUV parameters between OSEM and BPL were statistically significant (Table 1). The largest difference was in liver SUVmean (mean difference 0.17, 95 % CI 0.14–0.21). The average background SNR on OSEM was 10.2 (range 6.9–15.0), increasing to 12.3 on BPL (range 8.0–17.9, p < 0.0001) (Table 1).

Nodule analysis: entire cohort

There was a statistically significant difference in overall nodule SUVmax (mean difference 2.8, p < 0.00001), SNR (mean 17.0 on OSEM almost doubling to 41.1 on BPL, p < 0.0001) and SBR (mean difference 1.7, p < 0.00001), with mean increase %ΔSUVmax of 50.0 % (median 40.5 %, range −16.7 to +301 %). There was a statistically significant inverse correlation between %ΔSUVmax and nodule size (p = 0.0028). Results of this analysis are described in Table 2.

Nodule analysis: size

Consistent with analysis of the entire cohort, there were statistically significant differences between BPL and OSEM in nodule SUVmax, SBR and SNR in both ≤10 mm and >10 mm categories. Results of this analysis are detailed in Table 2.

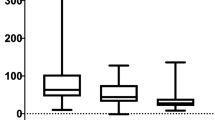

Nodule analysis: FDG uptake

The same trends in change to SUVmax, SBR and SNR were observed in FDG-positive (above-background) nodules (all p < 0.00001). There was also a stronger correlation between %ΔSUVmax and nodule size in this group compared to the entire cohort (p < 0.00001 vs 0.0028). However in FDG-negative (at/below-background) nodules, statistical significance of SUVmax and SBR change was relatively weaker (p = 0.031 and 0.0076, respectively). There was no statistically significant change to SBR or %ΔSUVmax in FDG-negative nodules (p = 0.196 and 0.522, respectively). Results of this analysis are summarised in Table 2 and Fig. 1.

In view of the stronger correlation between %ΔSUVmax and nodule size in FDG-positive nodules compared to the entire cohort, a sub-analysis was performed according to size. The difference in %ΔSUVmax between FDG-positive nodules ≤10 mm and >10 mm was accentuated in this subgroup (92.1 % vs 45.3 %, p = 0.00013).

Nodule analysis: aetiology

When categorised into three groups, NSCLC, metastases and benign, there was an observed difference in %ΔSUVmax between the groups (mean 65.2 % in metastases, 46.6 % in NSCLC, 35.0 % in benign), but this was not statistically significant. The highest %ΔSUVmax in metastases could not be accounted for by differences in nodule size, as there was no significant difference in nodule size among the three groups (Table 3). The OSEM SUVmax, BPL SUVmax and %ΔSUVmax of the three groups are summarised in Table 3.

Visual analysis of FDG uptake

On visual analysis of FDG uptake on OSEM compared to BPL (Table 4), scores were concordant in 113 nodules (93 %). Seven nodules had a higher score on BPL (six background increased to above-background, of which four were malignant and two benign; one below-background increased to background–malignant), and one nodule had a lower score on BPL (above-background decreased to below-background–malignant).

Four of the seven nodules that scored higher on BPL using visual analysis were ≤10 mm. By semi-quantitative criteria, three of these seven nodules were FDG-negative on OSEM, one remaining FDG-negative on BPL by semi-quantitative criteria. The latter nodule was scored as below-background on OSEM, and background on BPL. The two benign nodules in this group were FDG-positive by semi-quantitative criteria on both algorithms. These results are summarised in Table 4.

Diagnostic performance

ROC curves were plotted to evaluate the usefulness of BPL and OSEM to detect malignant nodules on the basis of semi-quantitative criteria (Fig. 2). The AUC values were 0.719 (p = 0.009) and 0.709 (p = 0.006), respectively, with no statistically significant difference between the two algorithms (p = 0.98). The optimum SUVmax threshold for detection of malignancy was 3.5 and 4.4 for OSEM and BPL, respectively. The sensitivities, specificities and accuracies at these thresholds as an entire cohort and categorised according to size are summarised in Table 5. Across these groups, there was an increase in accuracy and a divergence in sensitivity and specificity between OSEM and BPL, with sensitivity tending to increase and specificity tending to decrease with BPL. The greatest increases in accuracy (48 % to 58 %) and sensitivity (44 % to 56 %) were demonstrated in nodules ≤10 mm.

On the basis of visual criteria, sensitivity and accuracy was consistently higher across the cohort compared to semi-quantitative criteria, although specificity was lower (Table 5). The differences in accuracy and sensitivity between OSEM and BPL were relatively smaller, if not unchanged (Table 5). The largest change in sensitivity was by 3 % (84 % to 87 % in the entire cohort), and 2 % in accuracy (84 % to 82 % in nodules >10 mm).

Discussion

Overall there was an almost twofold increase in nodule SNR across the cohort. Significant increments in SUVmax and SBR in FDG-positive nodules (SUVmax>blood pool SUVmean) were also observed with an average SUVmax increase of 3.2 (56 %) and SBR increment of 2.0, while changes in background SUV parameters were minimal (mean difference ≤0.17, Table 1). These changes are best illustrated by two example cases in Figs. 3 and 4. There was no significant increase in SUVmax and SBR in FDG-negative nodules. There was an inverse correlation between nodule size and %ΔSUVmax: for nodules ≤10 mm %ΔSUVmax was 92.1 %, compared to nodules >10 mm (%ΔSUVmax 45.3 %).

Coronal PET and PET/CT images demonstrating an 11-mm left upper lobe adenocarcinoma which had an SUVmax of 2.1 on OSEM, and 4.6 on BPL. Liver and descending aorta SUVmean differed by 0.1 between the two reconstructions. SNR increased by more than twofold from 15 to 35. All PET images are displayed on SUV scale 0–6

Axial PET and PET/CT images of an 8-mm right upper lobe metastasis from colorectal adenocarcinoma which had an SUVmax of 1.8 on OSEM, and 4.4 on BPL. Liver and descending aorta SUVmean differed by up to 0.28. Signal-to-noise ratio increased by more than twofold from 8 to 20. All PET images are displayed on SUV scale 0–6

This overall observation is considered to be due to BPL running to ‘effective convergence’ [19, 20], compared to the limited convergence of OSEM (reported here using two iterations). The greater differences in SUVmax in nodules ≤10 mm would also be due to BPL including PSF modelling in the reconstruction process, giving higher values for small lesions compared to reconstructions that do not include PSF modelling, with SUVmax approaching phantom truth [11, 13]. Interestingly, the greatest increases were seen in small malignant nodules. While comparison between OSEM with PSF modelling (SharpIR on GE systems) and BPL might seem more appropriate, the former reconstruction has not been adopted as standard of care in our institution. This is due to the increased intervoxel covariance seen with the PSF modelling (Fig. 2 in [22]), which causes images to appear very heterogeneous, for example in the liver.

The effect of BPL on nodule evaluation and diagnostic performance was assessed using semi-quantitative and visual criteria. Improvements in sensitivity and accuracy were observed with BPL when semi-quantitative criteria were applied. This was accompanied by decreases in specificity which were expected, considering there was no significant difference in %ΔSUVmax between benign and malignant nodules and AUC values using either algorithm. Remarkably, sensitivity and accuracy were consistently higher using visual criteria compared to semi-quantitative criteria (e.g. accuracy 62–67 % on semi-quantitative criteria compared to 78–79 % on visual criteria), and the differences of these parameters between OSEM and BPL were less varied using visual criteria. The specificities were generally lower for BPL, although this may be accounted for by the use of FDG uptake as a single determinant of malignancy. It is anticipated that the incorporation of other factors such as clinical history, risk, prior imaging and CT appearance would improve specificity alongside the other diagnostic performance parameters.

The two most used methods to analyse 18F-FDG PET data for distinguishing benign from malignant lung nodules are either by subjectively assessing FDG avidity in comparison to background or using semi-quantitative analyses, SUV, most commonly SUVmax, with variable thresholds used as a cut-off to separate benign from malignant disease. In their widely cited meta-analysis, Gould et al. demonstrated that semi-quantitative analysis did not improve the accuracy of 18F-FDG PET in the diagnosis of pulmonary nodules in comparison to subjective visual analysis [1], and our observations are generally consistent with this finding. Other groups have also demonstrated visual analysis of 18F-FDG PET to be useful [7, 23]. Potentially, when either a semi-quantitative method or subjective visual analysis is used to differentiate benign from malignant disease, a higher threshold to report a nodule as benign may be appropriate.

Factors which influence SUV, and in turn affect semi-quantitative analysis, include blood glucose levels, radiotracer uptake times and respiratory movement [24]; the last of these being of particular relevance to lung nodules. Our study suggests that BPL does not improve the differentiation of benign from malignant nodules when compared to conventional OSEM analysis. However, this may be because we did not include enough benign nodules to enable a separation of nodules with borderline FDG avidity to show that BPL increases the detectable signal from those that are malignant, and those that are not. This seems unlikely to be the case, because non-malignant FDG-avid nodules are just as likely to have their visibility and SUVs increased as are malignant nodules. As such, using BPL instead of OSEM improves the sensitivity of PET/CT in nodule characterisation but does not appear to improve its specificity.

The value of BPL is most likely to be its ability to provide better visibility and more accurate quantitative data. This has been shown in phantom studies [15, 25] and our results demonstrate this advancement specifically in small nodules. This should enable PET/CT to be used in the assessment of nodules currently not thought suitable for imaging, potentially 6- to 9-mm nodules, when a low SUV or visibility is known to be an inaccurate assessment of their true metabolic activity. In contrast to the clinical setting of the solitary pulmonary nodule in patients without a history of known malignancy, BPL may be of particularly added value in assessing small nodules in the context of known malignancy. The highest %ΔSUVmax was observed in metastatic nodules in our cohort (65.1 %, Table 3).

Alongside the small numbers of benign nodules analysed, this study found relatively low AUC values derived compared to larger group data [1], owing to the stand-alone use of SUVmax as a single determinant of malignant involvement. Although, this supports the published observations that semi-quantitative analysis does not improve the accuracy of FDG-PET in lung nodule assessment.

Conclusion

The use of BPL, an iterative reconstruction technique using a Bayesian penalised likelihood reconstruction algorithm, results in a significant increase in signal-to-noise and signal-to-background measures in comparison to conventional OSEM reconstruction. While it does not improve the overall accuracy of 18F-FDG PET/CT for differentiating benign from malignant nodules, it appears to provide a more accurate report on the metabolic activity of the nodules. When a semi-quantitative analysis is applied in the assessment of pulmonary nodules whose signal is reconstructed using BPL, a higher SUVmax threshold may be warranted owing to the general increase in SUVmax values in comparison to conventional OSEM.

References

Gould MK, Maclean CC, Kuschner WG, Rydzak CE, Owens DK (2001) Accuracy of positron emission tomography for diagnosis of pulmonary nodules and mass lesions: a meta-analysis. JAMA 285:914–924

Fletcher JW, Kymes SM, Gould M et al (2008) A comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of 18F-FDG PET and CT in the characterization of solitary pulmonary nodules. J Nucl Med 49:179–185

van Tinteren H, Hoekstra OS, Smit EF et al (2002) Effectiveness of positron emission tomography in the preoperative assessment of patients with suspected non-small-cell lung cancer: the PLUS multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 359:1388–1393

Maffione AM, Grassetto G, Rampin L et al (2014) Molecular imaging of pulmonary nodules. AJR Am J Roentgenol 202:W217–W223

Khalaf M, Abdel-Nabi H, Baker J, Shao Y, Lamonica D, Gona J (2008) Relation between nodule size and 18F-FDG-PET SUV for malignant and benign pulmonary nodules. J Hematol Oncol 1:13-8722-1-13

Kim SK, Allen-Auerbach M, Goldin J et al (2007) Accuracy of PET/CT in characterization of solitary pulmonary lesions. J Nucl Med 48:214–220

Nomori H, Watanabe K, Ohtsuka T, Naruke T, Suemasu K, Uno K (2005) Visual and semiquantitative analyses for F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose PET scanning in pulmonary nodules 1 cm to 3 cm in size. Ann Thorac Surg 79:984–988

Adams MC, Turkington TG, Wilson JM, Wong TZ (2010) A systematic review of the factors affecting accuracy of SUV measurements. AJR Am J Roentgenol 195:310–320

Kinahan PE, Fletcher JW (2010) Positron emission tomography-computed tomography standardized uptake values in clinical practice and assessing response to therapy. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 31:496–505

Tong S, Alessio AM, Kinahan PE (2010) Image reconstruction for PET/CT scanners: past achievements and future challenges. Imaging Med 2:529–545

Alessio AM, Stearns CW, Tong S et al (2010) Application and evaluation of a measured spatially variant system model for PET image reconstruction. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 29:938–949

Lasnon C, Hicks RJ, Beauregard JM et al (2012) Impact of point spread function reconstruction on thoracic lymph node staging with 18F-FDG PET/CT in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Nucl Med 37:971–976

Bettinardi V, Presotto L, Rapisarda E, Picchio M, Gianolli L, Gilardi MC (2011) Physical performance of the new hybrid PETCT discovery-690. Med Phys 38:5394–5411

Hudson HM, Larkin RS (1994) Accelerated image reconstruction using ordered subsets of projection data. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 13:601–609

Ross S (2013) Q.Clear (GE Healthcare White Paper). http://www3.gehealthcare.co.uk/~/media/documents/us-global/products/petct/whitepaper/q%20clear/ge-healthcare-white-paper_qclear.pdf. Accessed 16 Apr 2015

Geman S, McClure DE (1987) Statistical methods for tomographic image reconstruction. Bull Int Stat Inst 52:5–21

Mumcuoglu EU, Leahy RM, Cherry SR (1996) Bayesian reconstruction of PET images: methodology and performance analysis. Phys Med Biol 41:1777–1807

Nuyts J, Beque D, Dupont P, Mortelmans L (2002) A concave prior penalizing relative differences for maximum-a-posteriori reconstruction in emission tomography. IEEE Trans Nucl Sci 49:56–60

Asma E, Ahn S, Ross SG, Chen A, Manjeshwar RM (2012) Accurate and consistent lesion quantitation with clinically acceptable penalized likelihood images. Nuclear Science Symposium and Medical Imaging Conference (NSS/MIC), 2012 IEEE:4062–4066

Ahn S, Fessler JA (2003) Globally convergent image reconstruction for emission tomography using relaxed ordered subsets algorithms. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 22:613–626

Hanley JA, McNeil BJ (1983) A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology 148:839–843

Rahmim A, Qi J, Sossi V (2013) Resolution modeling in PET imaging: theory, practice, benefits, and pitfalls. Med Phys 40:064301

Herder GJ, Golding RP, Hoekstra OS et al (2004) The performance of (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in small solitary pulmonary nodules. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 31:1231–1236

Kwee TC, Cheng G, Lam MG, Basu S, Alavi A (2013) SUVmax of 2.5 should not be embraced as a magic threshold for separating benign from malignant lesions. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 40:1475–1477

McGowan DR, Teoh EJ, Franklin J, Bradley KM, Gleeson FV, Fenwick JD (2014) Improvement using a new Bayesian penalised likelihood reconstruction (QClear) on contrast recovery and background variability in the NEMA image quality phantom and patients. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 41:S172

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alice Asseraf and Hugo Arques at GE Healthcare for their assistance in the processing of sinograms using BPL.

The scientific guarantor of this publication is Prof. Fergus Gleeson. The authors of this manuscript declare no relationships with any companies whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article. Daniel McGowan is funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Healthcare Scientist Chief Scientific Officer Doctoral Award. The research was supported by the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre Programme. This paper presents independent research funded by the NIHR. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

No complex statistical methods were necessary for this paper. Institutional review board approval was not required because informed consent is not required for retrospective reviews of this nature in our institution. Written informed consent was not required for this study because informed consent is not required for retrospective reviews of this nature in our institution. Methodology: retrospective, diagnostic or prognostic study, performed at one institution.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Teoh, E.J., McGowan, D.R., Bradley, K.M. et al. Novel penalised likelihood reconstruction of PET in the assessment of histologically verified small pulmonary nodules. Eur Radiol 26, 576–584 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-015-3832-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-015-3832-y