Abstract

In terrestrial mammals, the respiratory turbinate bones within the nasal cavity are employed to conserve heat and water. In order to investigate whether environmental temperature affects respiratory turbinate structure in phocids, we used micro-computed tomography to compare maxilloturbinate bone morphology in polar seals, grey seals and monk seals. The maxilloturbinates of polar seals have much higher surface areas than those of monk seals, the result of the polar seals having more densely packed, complex turbinates within larger nasal cavities. Grey seals were intermediate; a juvenile of this species proved to have more densely packed maxilloturbinates with shorter branch lengths than a conspecific adult. Fractal dimension in the densest part of the maxilloturbinate mass was very close to 2 in all seals, indicating that these convoluted bones evenly fill the available space. The much more elaborate maxilloturbinate systems in polar seals, compared with monk seals, are consistent with a greater need to limit respiratory heat loss.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

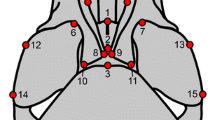

Described as “one of the most distinctive of mammalian features” (Hillenius 1992), the turbinate bones are thin, scroll-like or branched bony plates which partially fill the nasal cavity (Negus 1958; Moore 1981; Hillenius 1992). Maxilloturbinates (Fig. 1) are found on each side of the cavity, attached to the maxillary bone: their complexity and shape vary considerably in different groups of mammals (Negus 1958). The maxilloturbinates are in the line of airflow and are covered by respiratory epithelium (Van Valkenburgh et al. 2014a). They form the largest part of the functional division referred to as the ‘respiratory turbinates’ and represent the focus of the present study. The nasoturbinates are smaller and much simpler in structure. In carnivores, one is suspended from each of the right and left nasal bones in the dorsal part of the nasal cavity. Domestic cat nasoturbinates are at least partially covered in olfactory epithelium (Van Valkenburgh et al. 2014a), but the main role of nasoturbinates in carnivores may be to help direct airflow to the olfactory region in the posterior part of the nasal cavity (Van Valkenburgh et al. 2014b). In this olfactory region, blind recesses are formed between complex turbinates covered in olfactory epithelium. These turbinates may be attached to ethmoid, frontal or sphenoid bones in carnivores (Van Valkenburgh et al. 2011). Ethmoturbinates, frontoturbinates and interturbinates have been described in domestic dogs, but their precise identification is difficult without recourse to an ontogenetic series, and nomenclature has varied in different studies (Wagner and Ruf 2019). Here, these bones will be referred to collectively as ‘olfactory turbinates’ (Fig. 1), although the anterior part of the first ethmoturbinate was actually found to be covered in respiratory epithelium in Felis and Lynx (Van Valkenburgh et al. 2014a).

Functionally, the respiratory turbinates are used for heat and water exchange (Cole 1954; Jackson and Schmidt-Nielsen 1964). By the time it reaches the lungs, inspired air is warmed to body temperature and saturated with water vapour. Exhalation in the absence of any kind of water conservation mechanism would lead to all this water vapour simply being lost. However, when an animal breathes in through its nose, the respiratory turbinate mucosa over which the air passes is cooled in the process. When breathed back out across the same surface, the exhaled gas is cooled to a value below core body temperature, reducing heat loss. This also leads some of the water vapour, which otherwise would have been exhaled, to condense on the turbinate mucosa, whence it can be absorbed back into the body. Given their high ventilatory rates, respiratory heat and water conservation is particularly important in endotherms, even for those from mesic environments (Hillenius 1992). Some mammals such as domestic cats, rats and rabbits have an inflatable region on either side of the nasal septum called the ‘swell body’. Changes in the level of inflation of swell bodies, which may be cyclic, will change the patterns of airflow through the nose and might therefore be used to exert some control over this heat-exchange function (Negus 1958; Bojsen-Moller and Fahrenkrug 1971).

Phocid seals (Carnivora: Phocidae) are typically marine mammals, found throughout the world but most abundant in colder waters including polar regions. Seals have long been known to have relatively small olfactory turbinates, linked to a poor sense of smell, but branched-type (‘dendritic’) maxilloturbinates with a high surface area (Scott 1954; Negus 1958; Folkow et al. 1988; Mills and Christmas 1990; Van Valkenburgh et al. 2014b). The lack of a ‘swell body’ in seals implies that air must always pass through the narrow maxilloturbinate passageways (Negus 1958). Turbinate surface area measurements have been made from physical sections of seal noses (Huntley et al. 1984; Folkow et al. 1988; Schroter and Watkins 1989) and more recently from CT data (Van Valkenburgh et al. 2011). Van Valkenburgh et al. (2011) made detailed measurements of turbinate area from five species of aquatic carnivores: the phocid seals Hydrurga leptonyx, Mirounga angustirostris and Neomonachus tropicalis, the sealion Zalophus californianus and the sea otter Enhydra lutris. Relative to body mass or skull length, these animals were found to have significantly lower olfactory turbinate surface areas than terrestrial carnivores, while their respiratory turbinate surface areas tended to be larger. Exhaled gas in seals can be 20 °C below body temperature, depending on the environmental air temperature (Huntley et al. 1984; Folkow and Blix 1987). The resulting savings in respiratory water loss can be very impressive, with recoveries of over 80% recorded in the grey seal Halichoerus grypus (Folkow and Blix 1987) and over 90% in the northern elephant seal, Mirounga angustirostris (Lester and Costa 2006), again depending on environmental conditions.

Intriguingly, while Van Valkenburgh et al. (2011) found the maxilloturbinates of the phocid seals Hydrurga and Mirounga to be densely packed with high surface areas, the Caribbean monk seal Neomonachus tropicalis had much less elaborate maxilloturbinates, representing “perhaps the least respiratory surface area for its size in the entire sample” of 16 carnivore species. All marine seals should benefit from reducing respiratory water loss, given that they lack fresh water to drink. If anything, monk seals might be under more intense pressure in this regard than seals from colder environments, given that their cutaneous water losses would be expected to be higher when hauled out. However, if thermoregulation rather than water conservation represents the major selective pressure on respiratory turbinate structure in phocids, seals from higher latitudes would be expected to have better-developed respiratory turbinates than monk seals. The relatively low maxilloturbinate surface area of N. tropicalis, which became extinct probably in the 1970s or 1980s (LeBoeuf et al. 1986), suggests that this might indeed be the case. Whether the two living species of monk seals, the Hawaiian monk seal (N. schauinslandi) and the Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus), have similarly low maxilloturbinate surface areas has not previously been examined.

The aim of this study was to investigate differences in turbinate morphology, with regard to the hypothesis that heat conservation rather than water conservation is the main selective pressure on respiratory turbinate structure in seals. As in previous studies of respiratory turbinate surface areas, we chose to examine the maxilloturbinates only, since these bones are relatively easy to distinguish from the surrounding bones of the skull and represent the great majority of ‘respiratory’, as opposed to ‘olfactory’, turbinate surface area (Van Valkenburgh et al. 2011; Green et al. 2012). We measured maxilloturbinate surface areas in all three species of monk seals, two Antarctic seals (Ross and leopard), two Arctic seals (hooded and bearded) and the grey seal. The grey seal, Halichoerus grypus, is a cold-water species from the North Atlantic. Although it occurs in Greenland, Iceland, northern Norway and Russia (Boehme et al. 2012), it is not regarded as a true Arctic species, unlike hooded and bearded seals which may spend their entire lives within the Arctic region and breed on sea ice (Blix 2005).

Materials and methods

Micro-computed tomograms were made of 11 prepared skulls of eight seal species from public and private collections (Table 1): no animal was harmed for the purposes of this study. The measurements made from the scan data are described below. Body mass was unknown for most of the specimens examined here and is in any case very variable in phocid seals, as blubber thickness rises and falls throughout the year (e.g. Lønø 1970; Nilssen et al. 1996). We therefore used skull condylobasal length (CBL) as an index of body size.

Specimens

One skull of each of the following four polar phocids was examined: bearded seal (Erignathus barbatus; female), hooded seal (Cystophora cristata; male), leopard seal (Hydrurga leptonyx; male) and Ross seal (Ommatophoca rossii; male), the first two being Arctic species, the second two Antarctic. These skulls came from the personal research collection of ASB. The leopard seal had weighed only 178 kg and was therefore deemed to be immature, but the other skulls came from adults. Two skulls of the grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) were examined. One was an adult female skull from the Natural History Museum, University of Oslo (NHMO 7367). The other came from a 14-kg female neonate, a casualty from the Norfolk Wildlife Hospital, UK, which had been prepared in 1998 and is housed in the Veterinary Anatomy Museum, University of Cambridge (SE1). Two Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus) specimens were examined: an unsexed skull from the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge (UMZ K7781) and a male skull from The Natural History Museum, University of Oslo (M115). Two Caribbean monk seal (Neomonachus tropicalis) specimens were also examined: an unsexed skull from the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge (UMZ K7801) and a male skull from The Natural History Museum, London (NHMUK 1889.11.5.1). The single examined skull of a Hawaiian monk seal (Neomonachus schauinslandi) was from a juvenile male specimen belonging to The Natural History Museum, London (NHMUK 1958.11.26.1). The condylobasal lengths of these specimens are given in Table 1.

Our sample size was unfortunately limited by specimen availability, scanning resources and the extremely labour intensive image processing described later. Comparable studies have also been based, by necessity, on a very restricted number of specimens (Craven et al. 2007; Van Valkenburgh et al. 2011; Xi et al. 2016).

MicroCT scanning procedure

The skulls of the London and Cambridge specimens were CT scanned at the Cambridge Biotomography Centre. Each skull was separately placed within a Nikon XT H 225 CT scanner on radiotranslucent material in such a way that the tomograms produced were approximately in the transverse plane and covered the anterior skull. Tomograms were reconstructed using CT Agent XT 3.1.9 and CT Pro 3D XT 3.1.9 (Nikon Metrology, 2004–2013). Cubic voxel side lengths were 57–100 μm. The remaining specimens were scanned at The Natural History Museum, University of Oslo, Norway, also using a Nikon Metrology XT H 225 ST CT scanner. Cubic voxel side lengths were 60–75 μm. Further details of the scans are provided as Online Resource 1.

Figure 1 was constructed using AVIZO 9.5 software (ThermoFisher Scientific, Hillsboro, Oregon, USA) and Fig. 6 using Stradview 6.0 (Graham Treece and Andrew Gee, Cambridge, UK).

Image processing and measurement

Image processing for the purpose of maxilloturbinate surface area measurement was performed on a subset of equally spaced tomograms. The tomograms chosen ranged from one in three to one in five sections, depending on specimen, so as to obtain a comparable number of processed sections (between 149 and 203) encompassing the whole maxilloturbinate region.

Processing consisted of several steps (Fig. 2), initially performed using ImageJ 1.52b (Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health, USA). The raw tiff tomograms (Fig. 2A) were first subjected to the Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) technique, using the ImageJ plugin developed by Stephan Saalfeld (2010). CLAHE, which enhances local contrast, has previously been used to help distinguish thin turbinate bone structures in carnivores including seals (Van Valkenburgh et al. 2011). We then used ImageJ’s ‘Unsharp Mask’ filter to sharpen the image (Fig. 2B). The default thresholding function within ImageJ was used to convert each image to black-and-white, and then the ImageJ ‘Despeckle’ function was used to remove stray pixels (Fig. 2C). Different threshold settings were sometimes needed for different regions of the nasal cavity of a given specimen, depending on turbinate thickness and density. The settings chosen for the CLAHE, unsharp mask and threshold procedures for each specimen were determined by eye, by the same member of the team (MJM), the goal being that the final image should show even the thinnest turbinate bones with minimal noise.

A representative tomogram section through the nasal cavity of Monachus monachus (NHMO M115), showing the image processing procedure used to isolate the maxilloturbinates (see “Materials and methods”). A Raw tomogram. B Following the CLAHE and unsharp mask procedures. C Following thresholding and automated despeckling. D The final maxilloturbinate cross-section, following the manual removal of the surrounding skull bones, teeth, nasal septum and those pixels considered to be noise

Although the processes described above allowed the maxilloturbinates to stand out well from the background they also introduced noise, especially in the wider regions of air-space found between turbinate bones and between turbinates and nasal cavity wall. Pixels considered to represent noise were painstakingly and manually deleted from each tomogram, with visual reference to pre-threshold scans. Some of the scans, for example those of Cystophora and the adult Halichoerus, proved to require more manual editing than others, owing to poorer signal to noise ratios. Residual soft tissue within the nasal cavity was most evident in the Hawaiian and one of the Caribbean monk seals: this was also manually removed from the tomogram sections, wherever identifiable. All skull elements with the exception of the maxilloturbinate bones, including the nasal septum, were also cropped out, and marrow spaces within thicker regions of the remaining maxilloturbinates were filled in so that they would not contribute to measured turbinate surface area. These processes were performed using GIMP 2.10 and Adobe Photoshop CS 8.0 (Adobe Systems Inc., 2003).

The resulting black-and-white images, which now showed only maxilloturbinates (Fig. 2D), were converted to Portable Network Graphics (PNG) format, and a custom-written program was used to establish the turbinate-air perimeter within each image. This program counted the edges where black pixels (‘bone’) were adjacent to white pixels (‘air’), according to the following rules which were designed to reduce the influence of pixellation on the total perimeter:

Black pixels with four edges exposed to ‘air’ or four edges exposed to ‘bone’ were not counted at all.

A black pixel with three edges exposed to ‘air’ was counted as 1 unit.

A black pixel with two adjacent edges exposed to ‘air’ (i.e. a corner) was counted as √2 units.

A black pixel with two opposite edges exposed to ‘air’ was counted as 2 units.

A black pixel with one edge exposed to ‘air’ was counted as 1 unit.

The total number of pixel units representing the turbinate perimeter in a given section was then converted to millimetres using the appropriate scaling factor, then multiplied by the distance between adjacent sections. The areas thus obtained were added together to generate an estimate of total (left plus right) maxilloturbinate surface area for that seal specimen.

In order to assess the repeatability of the procedure, a tomogram section which required relatively aggressive noise reduction was reprocessed twelve times on different days, using a range of CLAHE and unsharp mask settings following manual removal of noise. Of the twelve processed sections obtained, the maximum and minimum perimeters differed by under 3.5%. A second test was to compare surface areas of the right and left maxilloturbinate masses, within each specimen, the expectation being that these areas should be very close if the method is reliable. This was indeed the case in all but one specimen (see “Results”).

Nasal cavity cross-sectional areas were measured from the same transverse section tomograms. These were total areas, including not just the air-space but also the areas occupied by the maxilloturbinate bones. Right and left nasal cavities were considered together as one combined area. Areas could only be measured in the region where the bony perimeter of the nasal cavity was intact, or nearly so. The region measured extended from the rostral end of the maxilloturbinate zone where the skull bones separate to create the external nasal opening to the caudal end where the orbital vacuities open.

Measurements from re-oriented sections

The orientation of the maxilloturbinate mass within the nasal cavity differed slightly in different seal species. In Cystophora for example, the dorsal part of the maxilloturbinate mass extends caudally, while the ventral part extends rostrally, giving the overall maxilloturbinate mass a sigmoid shape in the parasagittal section shown in Fig. 1B. As a result, transverse sections through the caudal nasal region of Cystophora showed less densely packed maxilloturbinates ventrally, while in the rostral nasal region the maxilloturbinates were less densely packed dorsally. This was also the case in the adult Halichoerus and Ommatophoca, but the effect was less exaggerated in other seals such as Erignathus (Fig. 1A). The measurements described next, such as hydraulic diameter, complexity and fractal dimension, would be affected by any uneven distribution of maxilloturbinates within the planes of the tomogram sections, as seen in Fig. 3D, G, H. In order to make measurements more comparable between species, it was necessary to re-orient the planes of the sections so as to pass right through the middle of the maxilloturbinate mass. To achieve this, the raw tomogram stack was re-oriented using MicroView 2.5.0 (Parallax Innovations, Inc. 2018), and a section was chosen by eye such that the maxilloturbinates filled the nasal cavity as evenly and densely as possible (Fig. 4). The process was repeated twice more, on different days, to yield three separate estimates of the re-oriented section which showed the most even, dense packing.

Transverse tomogram sections through the maxilloturbinate region in eight species of seals, shown to scale. In each case, the section calculated as having the highest individual maxilloturbinate perimeter is shown. The maxilloturbinates are shown in black, superimposed onto the grey background of the nasal cavity. A Caribbean monk seal Neomonachus tropicalis UMZC K7801 (turbinates damaged); B Hawaiian monk seal N. schauinslandi NHMUK 1958.11.26.1; C Mediterranean monk seal Monachus monachus UMZC K7781; D adult grey seal Halichoerus grypus NHMO 7367; E leopard seal Hydrurga leptonyx; F bearded seal Erignathus barbatus; G Ross seal Ommatophoca rossii; H hooded seal Cystophora cristata. The less dense packing of the turbinates dorsally in Halichoerus and ventrally in Ommatophoca and Cystophora reflects the orientations of the maxilloturbinate masses in these species

Re-oriented tomogram sections through the nasal cavities of seals. The orientations were chosen such that the maxilloturbinates fill the available space as evenly and densely as possible. AMonachus monachus NHMO M115; BNeomonachus schauinslandi NHMUK 1958.11.26.1; C juvenile Halichoerus grypus; D adult H. grypus NHMO 7367; EHydrurga leptonyx; FErignathus barbatus; GOmmatophoca rossii; HCystophora cristata

This reorientation process was performed for every specimen except for the two Neomonachus tropicalis. It was concluded that the maxilloturbinates were damaged in these specimens (see “Discussion”) and so the results obtained from re-oriented images in these two cases would not be meaningful.

Hydraulic diameter and complexity

Hydraulic diameter is used in considerations of fluid flow in irregularly shaped ducts. It has been used to generate ‘characteristic diameters’ for airflow in different sections of the nasal passageways of other mammals (Craven et al. 2007; Xi et al. 2016). The hydraulic diameter Dh of the airway in a given section is calculated from the total cross-sectional area of the airway (Ac) and the perimeter of the maxilloturbinates (P) in that section, according to the following equation:

In their study of airflow through a rabbit nasal cavity, Xi et al. (2016) used the following equation to estimate the complexity (Cx) of airway borders in a given cross-section:

If the nasal cavities were perfectly circular and empty of turbinates, Dh (which has dimensions of length) would equal the diameter and the dimensionless Cx would equal 1. The more branched and complex the turbinates occupying the nasal cavity, the more the bony perimeter would increase relative to total airway area, resulting in Dh becoming smaller and Cx larger.

Dh and Cx were calculated from the re-oriented sections made through the densest regions of the maxilloturbinates. In each of these sections, the airway area Ac was calculated by measuring the total area occupied by the left and right maxilloturbinate masses, which includes the air-spaces between the bones, and subtracting from this the total area occupied by bone (i.e. black pixels). The air-space separating the maxilloturbinate mass from the surrounding nasal cavity, nasoturbinate and septum walls was not included in the calculation of Ac, nor were the perimeters of these surrounding structures included in P. These calculations also ignore the area occupied in vivo by soft tissue, i.e. the nasal mucosa, which was missing in the prepared skulls examined. The resulting measurements therefore refer to the maxilloturbinate mass only. Hydraulic diameter and complexity were calculated in this way for each of the three oblique cross-sections constructed from each seal specimen, and the mean values were taken.

Fractal dimension

Fractal dimension was calculated to assess how the maxilloturbinates in cross-section fill the available space. In a 2D tomogram, for any given square of side-length L contained within the maxilloturbinate region, a relationship can be calculated of the form:

where PL is the perimeter of the maxilloturbinates contained within that square, k is a constant and D is fractal dimension. A value of D = 2 indicates that the perimeter within a given area is directly proportional to the area considered, which would be expected if the maxilloturbinates evenly occupy the available space. Equation (3) can be rearranged to give:

Fractal dimension was calculated from the re-oriented sections described above. The total area occupied by the left maxilloturbinate mass was calculated, the square root of that area was taken as the first length L1 and the total perimeter of the left maxilloturbinate mass was taken as PL1. Then, a square of side-length equal to 0.5 L1 was selected, centred at the centroid of the left maxilloturbinate mass (Fig. 5A) and the perimeter of the turbinates within was measured. A smaller square with side-length 0.25 L1 was then selected in the centre of the first square (Fig. 5B), and the perimeter within was again calculated. This process was repeated (Fig. 5C), halving the side-length of each successive square, until reaching a square so small as to contain either all black or all white pixels: this was not used. A plot was then constructed of log(PL) against log(L) for all the areas considered. A least squares regression line was fitted, and the slope D of this regression line was determined (Fig. 5D). The original square of side-length 0.5 L1 was then moved to four other positions within the left maxilloturbinate mass of that same section and the process was repeated each time so as to obtain four more regression slopes. The four partially overlapping positions were chosen by translating the original square as far as possible in the y-axis and x-axis directions (i.e. up, down, left and right), such that it remained wholly within the left maxilloturbinate mass. The same procedure was repeated for the right maxilloturbinate mass and then for the left and right maxilloturbinate masses of the other two oblique sections produced for that specimen. The 30 regression slopes thus calculated were averaged to get a mean fractal dimension value for that seal specimen.

taken from a re-oriented section chosen such that the maxilloturbinates fill the available area as evenly and densely as possible. The enclosed area of the maxilloturbinates is (L1)2. A square of side-length 0.5 L1 is drawn in the centre of the maxilloturbinate region. B The square from (A), with another square of side-length 0.25 L1 at its centre. C The smaller square from (B), with another square of side-length 0.125 L1 at its centre. Smaller and smaller squares were selected in this way. D The graph shows the perimeter of the maxilloturbinates contained within each area plotted against L, on logarithmic axes, with a least squares regression line fitted. This process was repeated for four other squares within the same left maxilloturbinate mass section and then again on the right side (see “Materials and methods”)

Method for calculating fractal dimension. A Left maxilloturbinate mass of Erignathus,

Results

Anatomical description

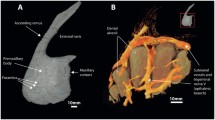

The maxilloturbinate masses were of a broadly similar shape in all seals. Comparing the three examples shown in Fig. 6, Monachus clearly has a smaller maxilloturbinate mass than the polar seals Erignathus and Ommatophoca. In rostral view, the overall width:height ratio is greatest in Erignathus, while in lateral view, the maxilloturbinate mass of Ommatophoca is more obliquely oriented than in the other two seals.

In finer detail, the branching maxilloturbinates on a given side of the nasal cavity in Monachus all ultimately arise from a single, short trunk connected to the maxilla (Fig. 3C, 4A). In three dimensions, this connection takes the form of a ridge which begins ventrolaterally in the posterior part of the nasal cavity and ends dorsolaterally towards the tip of the nose. In the posterior part of the nasal cavity, the maxilloturbinates are concentrated medially, with wide air channels surrounding them laterally and especially ventrally (Fig. 7C). In the central region, the maxilloturbinates occupy most of the nasal cavity right up to the nasal septum, although there is always a narrow space between the maxilloturbinate mass and the surrounding nasal cavity walls. Towards the rostral end of the nasal cavity, the maxilloturbinates become concentrated laterally.

Transverse tomogram sections through the posterior maxilloturbinate region in ACystophora cristata, BHydrurga leptonyx, CMonachus monachus UMZC K7781, DOmmatophoca rossii. NT = nasoturbinate; S = nasal septum. Note the open air-space between the nasoturbinates and the septum dorsally, visible in all species. The arrows in B–D indicate some of the roots of the maxilloturbinates, which differ in number in the different species. There are many such roots visible in Cystophora, in the region indicated with a bracket

The maxilloturbinates of Neomonachus schauinslandi (Fig. 3B, 4B) branch less than in Monachus, and the bones have wider spaces between them. The maxilloturbinates fill the nasal cavity much less fully, but the rounded contours of the right and left maxilloturbinate masses are symmetrical and match the shape of the nasal cavity around them. The maxilloturbinates in the two N. tropicalis specimens (Fig. 3A) have few branches and each occupy only a small, lateral part of the nasal cavity. It appeared that the finer divisions of the maxilloturbinates in these Caribbean monk seals had been broken off (see “Discussion”).

In all seals examined, the maxilloturbinates on each side are connected to the lateral nasal cavity wall through a single, dorsolateral ridge, in the rostral region. However, in species other than the monk seals, this ridge shortens and divides in the posterior part of the nasal cavity, such that transverse sections through this region showed the maxilloturbinates branching from multiple ‘trunks’ emerging from the lateral cavity wall. There were two such trunks in our specimen of Leptonyx, three in Halichoerus, four or five in Erignathus and Ommatophoca and around fifteen in Cystophora (Fig. 7).

In Monachus and Hydrurga in particular, the terminal branches of the maxilloturbinates are relatively long and curve around each other to form loops, a little like those of a fingerprint (Fig. 3C, E, 4A, E). Those of the other species have a more dendritic appearance, the turbinates being packed especially densely in Erignathus, Cystophora and Ommatophoca in the central part of their range (Fig. 1, 3F–H, 4F–H). There appeared to be a shorter distance between branch points in the juvenile Halichoerus: its multiple short, straight terminal branches give its maxilloturbinate mass a unique, ‘thorny’ appearance in cross-section (Fig. 8B). In the adult specimen of this species, the branches are elongated, especially towards the periphery, and the overall turbinate structure is less regular (Fig. 8A).

Transverse tomogram sections through the maxilloturbinate regions in adult (A) and juvenile (B) grey seals Halichoerus grypus, shown to scale. The section calculated as having the highest individual maxilloturbinate perimeter is shown in each case. The maxilloturbinates are shown in black, superimposed onto the grey background of the nasal cavity. The nasal septum was cartilaginous in this region in the juvenile and is not shown. The insets below show × 3 magnified views of parts of the maxilloturbinates: note that the maxilloturbinates of the juvenile have shorter branches, leading to a ‘thorny’ appearance

Beginning within the olfactory turbinate mass, the short and unbranched nasoturbinates extend downwards in all seals from the roof of the nasal cavity, on either side of the septum (Fig. 7). Between each nasoturbinate and the septum is an open air channel. Right and left channels run adjacent to each other along the top of the nasal cavity, becoming progressively more open rostrally as the nasoturbinates shorten and diverge from the septum.

Measurements

Measurements of maxilloturbinate surface areas are presented in Table 1, and the transverse sections of peak perimeter are shown in Figs. 3 and 8. The individual perimeters of the maxilloturbinates calculated from the tomograms rose to a peak and then fell again, proceeding from caudally to rostrally within the nasal cavity (Fig. 9). Peak values were much higher in the polar seals than in the monk seals; the two Halichoerus specimens were intermediate.

Maxilloturbinate perimeters calculated from transverse sections at different points along the nasal cavities of seals. The position is given in millimetres rostral to the most caudal point of the maxilloturbinates. Note that the peak maxilloturbinate perimeters are larger in the polar seals (solid blue lines) than in the grey seals (dotted grey) and the monk seals (dashed red), and the length of snout occupied by maxilloturbinates is also longer. The total maxilloturbinate surface area is represented by the area under each curve. Key: CC = hooded seal, Cystophora cristata; EB = bearded seal, Erignathus barbatus; HG = grey seal, Halichoerus grypus; HL = leopard seal, Hydrurga leptonyx; MM = Mediterranean monk seal, Monachus monachus; NS = Hawaiian monk seal, Neomonachus schauinslandi; NT = Caribbean monk seal, N. tropicalis; OR = Ross seal, Ommatophoca rossii

Total maxilloturbinate surface area was nearly three times higher in the polar seal with the lowest surface area (the immature Hydrurga) than in the monk seal with the highest surface area (Table 1; Fig. 10A). The adult Halichoerus fell between the polar and monk seals, but closer to the former. Maxilloturbinate area was over three times higher in the Monachus specimens than in Neomonachus schauinslandi. The Halichoerus pup had a maxilloturbinate surface area closer to those of Monachus than Neomonachus, although its skull was substantially smaller than that of any of our monk seals (Table 1).

Measurements of A total maxilloturbinate surface areas, B mean hydraulic diameters and C mean maxilloturbinate complexity values in monk seals (striped red), grey seals (dotted grey) and polar seals (solid blue). Species initials as in Fig. 9. NHMO = The Natural History Museum, University of Oslo; NHMUK = The Natural History Museum, London; UMZC = University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge

Left and right maxilloturbinate surface areas were found to be within 5% of each other in all but one specimen. In one N. tropicalis specimen (NHMUK 1889.11.5.1), one side was only 69% the area of the other. No consistent trend was observed across specimens in whether the right area or the left area was the larger.

The length of snout occupied by maxilloturbinates was greater in the polar seals and adult Halichoerus than in the monk seals (Fig. 9). The cross-sectional areas of the nasal cavities were also greater in these cold-water species (Fig. 11). The juvenile N. schauinslandi had the smallest cross-sectional areas, well below those of the juvenile grey seal.

Cross-sectional areas of the central nasal cavities, plotted as functions of position in polar seals (solid blue lines), grey seals (dotted grey) and monk seals (dashed red). The position is given in millimetres rostral to the most caudal point of the maxilloturbinates. Cross-sectional areas could only be assessed where the nasal cavity has complete bony walls. Species initials as in Fig. 9

Hydraulic diameter values, calculated from the re-oriented sections, were lower in the four polar seals than in the monk seals (Table 2; Fig. 10B). Hydraulic diameter was lower in the juvenile Halichoerus than in the adult and comparable to values in polar species, reflecting relatively densely packed maxilloturbinates. Maxilloturbinate complexity was highest in the polar seals and lowest in N. schauinslandi; values for the two Halichoerus specimens fell between the values calculated for our two Monachus specimens (Fig. 10C).

The log–log plots constructed in the calculation of fractal dimension values (30 per specimen: see “Materials and methods”) all showed tight, linear relationships, the lowest R2 value for any relationship being 0.934. Fractal dimension, calculated by averaging the slopes of these lines, was very close to 2 in all seal specimens examined. Values ranged between 1.97 and 2.10 according to species (Table 2).

In order to take skull size into account, maxilloturbinate surface areas were plotted against condylobasal lengths, using data both from this study and from Van Valkenburgh et al. (2011). A least squares regression line was fitted to the data representing the non-pinniped carnivore species sampled by Van Valkenburgh et al. (Fig. 12). Four data points representing N. tropicalis, two from the present study and two from Van Valkenburgh et al. (2011), all fall below this regression line. Our N. schauinslandi falls slightly above the line, with our two Monachus specimens further above. Turbinate areas of all four of our polar seals fall further above the regression line: all more than three standard deviations above it (calculated from vertical residuals). The two Hydrurga specimens studied by Van Valkenburgh et al. had similar turbinate areas to our immature specimen, but substantially longer skulls (440 and 462 mm, compared to our 326 mm); their measurements were only 1–2 standard deviations above the line. The remaining pinniped species (shown in grey in Fig. 12) occupy variable positions on or above the regression line. Two Zalophus californianus sealions measured by Van Valkenburgh et al. fall almost on the line, while the elephant seal Mirounga angustirostris falls above it and the two Halichoerus specimens measured in the present study are higher still.

Plotting maxilloturbinate surface area (y-axis) against skull condylobasal length (x-axis), on logarithmic axes, for a range of Carnivora including pinnipeds. The least squares regression line has been calculated for non-pinniped carnivores, including species with smaller condylobasal lengths than included here, using data from Van Valkenburgh et al. (2011). Its equation is shown. Key: cross = non-pinniped, solid blue symbols = polar seals, striped red symbols = monk seals, open grey symbols = other pinnipeds. Triangles represent pinniped measurements made in this study, squares represent pinniped measurements made by Van Valkenburgh et al. (2011). Species initials as in Fig. 9, with the addition of MA = Mirounga angustirostris and ZC = Zalophus californianus

Discussion

Limitations of this study

The methods used here to process the CT data clearly involved an element of subjectivity, but were chosen because the resulting black-and-white images were much better representations of turbinate structure than anything that we could achieve in an automated way, when compared with the original, greyscale tomograms. Manual editing and segmentation has been used in comparable studies of turbinate structure, when considering poorly resolved regions (Craven et al. 2007; Xi et al. 2016). Three findings attest to the internal consistency of our processing methods: (1) repeated processing of the same section yielded very similar measurements (see “Materials and methods”); (2) right and left maxilloturbinate areas were within 5% of each other in all but one specimen; and (3) total areas for our two Monachus specimens, one scanned in Cambridge and one in Oslo, were within 10% of each other (Table 1). As a result, we are confident that the striking differences in species turbinate density documented here, clearly visible by eye from Figs. 3 and 4, cannot be put down to measurement error. The area that we calculated for our immature Hydrurga lay in-between the two values given for larger specimens of this species by Van Valkenburgh et al. (2011), so it may be that our methods generate larger area estimates than those used in the earlier study.

The maxilloturbinate surface areas of our two Neomonachus tropicalis specimens were both extremely low (Table 1; Fig. 10A). Although our two specimens had similar turbinate morphology, we believe that the maxilloturbinates of both specimens were in fact damaged, the more delicate, peripheral bone being broken away and only the thicker structural elements remaining. The fact that one of these specimens had very different right and left maxilloturbinate surface areas is consistent with this conclusion. Although residing in different UK museums, both specimens had been collected by F.D. Godman in the Gulf of Mexico in the 1880 s, and it is therefore likely that the two skulls had been prepared, and damaged, in a similar way. We were unable to access any other usable specimens of this extinct species, but Van Valkenburgh et al. (2011) found maxilloturbinate areas which were twice as high in two specimens from the United States National Museum. The cross-section through the nasal cavity of N. tropicalis illustrated in their paper shows more extensive and elaborate maxilloturbinates than what we observed in our specimens, most closely resembling what we observed in N. schauinslandi. We believe that the Van Valkenburgh et al. (2011) values for this species are more accurate than ours, which should be discounted as coming from damaged specimens.

Maxilloturbinate surface area differences

This study has shown that the maxilloturbinate surface areas in polar seals are much larger than those of the monk seals. This is a result of (1) a nasal cavity of increased cross-sectional area, (2) a longer region of nasal cavity occupied by maxilloturbinates and (3) more complex and densely packed maxilloturbinates. This difference is clear when comparing Monachus to Erignathus and Ommatophoca, which have similar condylobasal lengths (Fig. 6; Table 1). Our Neomonachus tropicalis specimens, which were of comparable size, also had low nasal cavity cross-sectional areas, and maxilloturbinate areas were evidently very low in this species too (Van Valkenburgh et al. 2011). The only N. schauinslandi skull that we were able to examine was from a juvenile specimen, but this alone cannot account for its very low maxilloturbinate surface area because this area was considerably higher in both our Halichoerus pup, which was a much smaller animal, and in our immature Hydrurga.

In order to examine whether differences in maxilloturbinate surface area are simply a result of body size, an allometric scaling approach was taken (Fig. 12). Data points representing our seals were plotted on the regression of maxilloturbinate area on skull length, calculated for non-pinniped carnivores using data from Van Valkenburgh et al. (2011). Van Valkenburgh et al. showed that N. tropicalis has a smaller maxilloturbinate surface area than expected for a carnivore of its size. Our juvenile N. schauinslandi specimen had a surface area very close to expected, while Monachus has maxilloturbinates of relatively higher surface area than Neomonachus species. Halichoerus, from more northernly waters, has a still higher maxilloturbinate area for its size, while the polar seals Erignathus, Cystophora and Ommatophoca have the highest of all. The leopard seal Hydrurga has a lower maxilloturbinate area for its skull length than the other polar seals, but it should be noted that this species has a relatively long skull. No significant correlation of turbinate surface area with latitude was found among terrestrial canid and arctoid carnivores in a previous study, but comparisons between sister taxa (Canis lupus arctos vs. C. l. baileyi; Vulpes lagopus vs. V. macrotis; Ursus maritimus vs. U. arctos) suggested that the three Arctic species/subspecies have enlarged turbinate surface areas compared with their lower-latitude relatives (Green et al. 2012).

The widths of the airways between adjacent turbinate bones can assessed through calculation of hydraulic diameters. Hydraulic diameter in the maxilloturbinate region was found to take a minimum value of around 1 mm in a Labrador retriever mixed-breed dog (Craven et al. 2007) and around 0.7 mm in a New Zealand white rabbit (Xi et al. 2016). Both the dog and rabbit studies were performed using MRI scans on cadavers, which allowed imaging of the nasal mucosa. This was not possible in our study in which only the maxilloturbinate bones were considered. As a result, our airway cross-sectional area Ac is enlarged, leading to our calculated hydraulic diameter values being higher and complexity values lower than they should be in vivo. Xi et al. calculated complexity values between around 1.7 and 2.3 in the rabbit maxilloturbinate region, higher than in any of our seals. However, hydraulic diameters in our polar seals, taken from sections oriented to pass through the densest region, were lower than in the dog and comparable to that of the rabbit. Being much larger animals, this attests to the unusually dense packing of the maxilloturbinate bones in these seals.

The re-oriented cross-sections considered here had been chosen by eye such that the maxilloturbinates filled the available space as evenly and densely as possible. Maxilloturbinate fractal dimensions were close to 2 in all seals, indicating that these bones did indeed fill the nasal cavity evenly in the positions selected. The density of packing, and hence maxilloturbinate surface area for any given volume of cavity, varies according to species. Fractal dimension values slightly greater than 2.0 in Table 2 likely arise from the effects of noise on the regressions, in particular if the turbinate perimeters for the lowest areas sampled happened to be small.

Ontogenetic changes

The juvenile Halichoerus was included in this study mainly for comparison with our Neomonachus schauinslandi which was also a juvenile specimen. However, it is also interesting to recognize the differences between the juvenile and adult Halichoerus skulls. It is noteworthy that although complexity values did not differ between these specimens, hydraulic diameter was lower in the juvenile when compared to the adult. The highly branched maxilloturbinates in the juvenile filled the available space more densely than in the adult, in which the terminal divisions were longer. This suggests that the branching occurs early in development, with branch lengths increasing postnatally. The lower hydraulic diameter might help to compensate for the smaller overall maxilloturbinate area in the juvenile, which has a much smaller skull. Of course, comparing just two specimens can only be considered indicative: it would be worthwhile investigating ontogenetic changes in seal maxilloturbinate morphology in more detail.

Heat and water conservation by respiratory turbinate bones

Respiratory turbinates in seals, as in other mammals, reduce respiratory heat and water losses (Folkow and Blix 1987). This heat-exchange function will be improved if the total surface area exposed to the air stream is greater, the distance between the centre of the airstream and the surfaces is narrower, and the velocity of airflow is lower (Schmidt-Nielsen et al. 1970). The time required to achieve thermal equilibrium between the expired gas and turbinate surface is expected to depend strongly on the width of the air passageways between the turbinates, which can be varied by inflation of mucosal tissue overlying the bones (Schroter and Watkins 1989). There are substantial venous sinuses between the surface epithelium and the maxilloturbinate bone in seals (Boyd 1975; Folkow et al. 1988), but these were not taken into account in the measurements made in the present study.

Polar seals and the adult Halichoerus were found to have greater maxilloturbinate surface areas than monk seals (Fig. 10A), achieved in part by a greater packing density which is manifested in the low hydraulic diameter values (Fig. 10B). Both factors would be expected to improve heat exchange. In addition, the wider nasal cavities of these seals (Fig. 11) would lower airflow velocity for any given tidal volume, again augmenting heat exchange. Having wider nasal cavities would also help to offset the increased resistance to breathing conferred by the higher packing density.

While the polar seals live in near-freezing waters all year long, this is not the case for monk seals living around Hawaii, the Caribbean and the Mediterranean. Differences in air temperature, to which the seals are exposed when ashore, would exceed differences in water temperature. Neomonachus schauinslandi is known to feed at night and haul out during the day (Kenyon and Rice 1959; Parrish et al. 2002); animals may remain ashore for 2–3 days (Whittow 1978). When on land, this species could be subject to heat stress, as suggested by observations of seals seeking shady areas, moving to wet sand, changing posture or digging shallow wallows (Kenyon and Rice 1959; Whittow 1978). Like other pinnipeds (Matsuura and Whittow 1974) they do not pant, but may alternate periods of apnoea with periods of ventilation (Whittow 1978). This may contribute to reducing respiratory water losses: Lester and Costa (2006) observed the same in fasting northern elephant seals, Mirounga angustirostris. Seals have the ability to reduce their body temperature when at sea (Hill et al. 1987; Meir and Ponganis 2010), so it is possible that monk seals store heat when hauled out and subsequently lose the excess when they return to water.

Turning to a consideration of water balance, all the seal species examined live in marine environments without access to fresh water to drink. As well as the ‘free’ water obtained from their food, seals generate water from metabolism: Nordøy et al. (1992) have demonstrated that Halichoerus pups can cope with a 52-day period without food or water, meeting their needs through catabolism of body fat and protein. Arctic harp seals (Phoca groenlandica) are able to restore water balance after profound dehydration by drinking seawater (Hov and Nordøy 2007). For Halichoerus on land, Folkow and Blix (1987) have shown that the savings of respiratory water at high ambient temperature, when expired air temperature is also high, are minor. Expired air temperature does not change in response to experimental manipulations of water balance in this species (Skog and Folkow 1994). The need to conserve respiratory water might be expected to be greater for seals in warmer climates, but these studies together with our findings suggest that it may not be of paramount importance. However, in colder regions, seals would experience an increased need to conserve heat. We therefore conclude that heat rather than water conservation represents the more important selective pressure behind the much more elaborate turbinate structures in polar seals, in comparison with monk seals.

Phylogenetic and biogeographic implications

Halichoerus, Cystophora and Erignathus, all northern species, are placed in the Phocinae, while the other seals examined here are placed in the Monachinae (Fulton and Strobeck 2010; Fig. 13). Within the Monachinae, the monk seals are divided off as the Monachini, while the Antarctic seals Ommatophoca and Hydrurga are placed within the Lobodontini. Although there has been some debate in the palaeontological literature, opinion seems to be solidifying around the notion that phocids evolved in the North Atlantic or possibly the Paratethys sea region in the Oligocene (Arnason et al. 2006; Koretsky et al. 2016; Berta et al. 2018). This places their origin in relatively warm waters, following which there were separate dispersals to the Arctic (certain phocine seals) and Antarctic (lobodontine seals) (Koretsky and Barnes 2006; Berta et al. 2018). Lobodontine ancestors are thought to have migrated down the west coast of South America, perhaps by island-hopping around the Southern Ocean and reaching southern Africa from there (Govender 2015). Together with the distant phylogenetic placement of the Arctic and Antarctic seals, as shown in Fig. 13, this suggests that the very dense turbinate morphology in these two groups evolved independently as they reached colder waters.

Phylogenetic diagram showing the relationships between the phocid species examined in the present study, based on Fulton and Strobeck (2010). Branch lengths are not time calibrated. The habitat of each seal and its relative maxilloturbinate density are indicated on the right. Maxilloturbinate density can be considered to be the reciprocal of hydraulic diameter

It has been observed that some phocine seals have a posterolateral expansion of the maxilla which might accommodate expanded maxilloturbinates, while lobodontine seals are said to achieve the same through dorsoventral expansion of the nasal cavity (de Muizon and Hendey 1980). Consistent with this, we found Halichoerus, Cystophora and Erignathus to have maxilloturbinates which were relatively more expanded laterally than those of the lobodontines Ommatophoca and Hydrurga, giving them a more diamond-shaped profile in some cross-sections (e.g. Figs. 4, 6). While this morphological difference might appear to support the hypothesis of independent evolution of expanded maxilloturbinates, one population of the Pliocene lobodontine Homiphoca, found in South Africa, also had a posterolateral maxillary expansion (de Muizon and Hendey 1980). There was no obvious difference in the detailed morphology of the maxilloturbinate branches between Arctic and Antarctic seals considered collectively. Interestingly, the looped pattern observed in Hydrurga, which has the least dense and complex turbinates of the polar seals studied, resembles that of Monachus.

Whether the much simpler turbinate structures of monk seals are primitive for crown-group phocids or represent a reduction from an intermediate condition remains unclear. It should be noted, however, that monk seal maxilloturbinate surface areas are relatively close to the expected values for their skull length, by comparison with the general carnivore regression line of Fig. 12.

The clear associations we have found here between nasal structures and latitude offer potential insights into the climatic environments inhabited by fossil seal species, if the nasal regions of these animals are preserved.

References

Arnason U, Gullberg A, Janke A, Kullberg M, Lehman N, Petrov EA, Väinölä R (2006) Pinniped phylogeny and a new hypothesis for their origin and dispersal. Mol Phylogenet Evol 41:345–354

Berta A, Churchill M, Boessenecker RW (2018) The origin and evolutionary biology of pinnipeds: seals, sea lions, and walruses. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 46:203–228

Blix AS (2005) Arctic animals and their adaptations to life on the edge. Tapir Academic Press, Trondheim

Boehme L, Thompson D, Fedak M, Bowen D, Hammill MO, Stenson GB (2012) How many seals were there? The global shelf loss during the last glacial maximum and its effect on the size and distribution of grey seal populations. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0053000

Bojsen-Moller F, Fahrenkrug J (1971) Nasal swell-bodies and cyclic changes in the air passage of the rat and rabbit nose. J Anat 110:25–37

Boyd RB (1975) A gross and microscopic study of the respiratory anatomy of the Antarctic Weddell seal, Leptonychotes weddelli. J Morphol 147:309–335

Cole P (1954) Recordings of respiratory air temperature. J Laryngol Otol 68:295–307

Craven BA, Neuberger T, Paterson EG, Webb AG, Josephson EM, Morrison EE, Settles GS (2007) Reconstruction and morphometric analysis of the nasal airway of the dog (Canis familiaris) and implications regarding olfactory airflow. Anat Rec 290:1325–1340

de Muizon C, Hendey QB (1980) Late Tertiary seals of the South Atlantic Ocean. Ann South Afr Mus 2:91–128

Folkow LP, Blix AS (1987) Nasal heat and water exchange in gray seals. Am J Physiol 253:R883–R889

Folkow LP, Blix AS, Eide TJ (1988) Anatomical and functional aspects of the nasal mucosal and ophthalmic retia of phocid seals. J Zool 216:417–436

Fulton TL, Strobeck C (2010) Multiple markers and multiple individuals refine true seal phylogeny and bring molecules and morphology back in line. Proc Roy Soc B 277:1065–1070

Govender R (2015) Preliminary phylogenetic and biogeographic history of the Pliocene seal, Homiphoca capensis from Langebaanweg, South Africa. Trans R Soc South Afr 70:25–39

Green PA, Van Valkenburgh B, Pang B, Bird D, Rowe T, Curtis A (2012) Respiratory and olfactory turbinal size in canid and arctoid carnivorans. J Anat 221:609–621

Hill RD et al (1987) Heart rate and body temperature during free diving of Weddell seals. Am J Physiol 253:R344–R351

Hillenius W (1992) The evolution of nasal turbinates and mammalian endothermy. Paleobiology 18:17–29

Hov O-J, Nordøy ES (2007) Seawater drinking restores water balance in dehydrated harp seals. J Comp Physiol B 177:535–542

Huntley AC, Costa DP, Rubin RD (1984) The contribution of nasal countercurrent heat exchange to water balance in the northern elephant seal, Mirounga angustrirostris. J Exp Biol 113:447–454

Jackson DC, Schmidt-Nielsen K (1964) Countercurrent heat exchange in the respiratory passages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 51:1192–1197

Kenyon KW, Rice DW (1959) Life history of the Hawaiian monk seal. Pac Sci 13:215–252

Koretsky IA, Barnes LG (2006) Pinniped evolutionary history and paleobiogeography. In: Csiki Z (ed) Mesozoic and Cenozoic vertebrates and paleoenvironments. Ars Docendi, Bucharest, pp 143–153

Koretsky IA, Barnes LG, Rahmat SJ (2016) Re-evaluation of morphological characters questions current views of pinniped origins. Vestn Zool 50:327–354

LeBoeuf BJ, Kenyon KW, Villa-Ramirez B (1986) The Caribbean monk seal is extinct. Mar Mammal Sci 2:70–72

Lester CW, Costa DP (2006) Water conservation in fasting northern elephant seals (Mirounga angustirostris). J Exp Biol 209:4283–4294

Lønø O (1970) The polar bear (Ursus maritimus) in the Svalbard area. Norsk Polarinst Skri 149:1–103

Matsuura DT, Whittow GC (1974) Evaporative heat loss in the California sea lion and harbor seal. Comp Biochem Physiol A 48:9–20

Meir JU, Ponganis PJ (2010) Blood temperature profiles of diving elephant seals. Physiol Biochem Zool 83:531–540

Mills RP, Christmas HE (1990) Applied comparative anatomy of the nasal turbinates. Clin Otolaryngol 15:553–558

Moore WJ (1981) The mammalian skull. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Negus V (1958) The comparative anatomy and physiology of the nose and paranasal sinuses. E. & S. Livingstone Ltd., Edinburgh

Nilssen KT, Haug T, Grotnes PE, Potelov V (1996) Seasonal variation in body condition of adult Barents Sea harp seals, Phoca groenlandica. NAFO Sci Coun Stud 26:63–70

Nordøy ES, Stijfhoorn DE, Råheim A, Blix AS (1992) Water flux and early signs of entrance into phase III of fasting in grey seal pups. Acta Physiol Scand 144:477–482

Parrish FA, Abernathy K, Marshall GJ, Buhleier BM (2002) Hawaiian monk seals (Monachus schauinslandi) foraging in deep-water coral beds. Mar Mammal Sci 18:244–258

Saalfeld S (2010) https://imagej.net/Enhance_Local_Contrast_(CLAHE).

Schmidt-Nielsen K, Hainsworth FR, Murrish DE (1970) Counter-current heat exchange in the respiratory passages: effect on water and heat balance. Resp Physiol 9:263–276

Schroter RC, Watkins NV (1989) Respiratory heat exchange in mammals. Resp Physiol 78:357–368

Scott JH (1954) Heat regulating function of the nasal mucous membrane. J Larynol Otol 68:308–317

Skog EB, Folkow LP (1994) Nasal heat and water exchange is not an effector mechanism for water balance regulation in grey seals. Acta Physiol Scand 151:233–240

Van Valkenburgh B, Curtis A, Samuels JX, Bird D, Fulkerson B, Meachen-Samuels J, Slater GJ (2011) Aquatic adaptations in the nose of carnivorans: evidence from the turbinates. J Anat 218:298–310

Van Valkenburgh B, Smith TD, Craven BA (2014a) Tour of a labyrinth: exploring the vertebrate nose. Anat Rec 297:1975–1984

Van Valkenburgh B, Pang B, Bird D, Curtis A, Yee K, Wysocki C, Craven BA (2014b) Respiratory and olfactory turbinals in feliform and caniform carnivorans: the influence of snout length. Anat Rec 297:2065–2079

Wagner F, Ruf I (2019) Who nose the borzoi? Turbinal skeleton in a dolichocephalic dog breed (Canis lupus familiaris). Mammal Biol 94:106–119

Whittow GC (1978) Thermoregulatory behavior of the Hawaiian monk seal (Monachus schauinslandi). Pac Sci 32:47–60

Xi JA, Si XA, Kim J, Zhang Y, Jacob RE, Kabilan S, Corley RA (2016) Anatomical details of the rabbit nasal passages and their implications in breathing, air conditioning, and olfaction. Anat Rec 299:853–868

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Richard Sabin and Roberto Portela Miguez of The Natural History Museum, London, Matt Lowe of the University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge and Professor Øystein Wiik for facilitating the loan of their specimens. The Norfolk Wildlife Hospital kindly donated the juvenile grey seal specimen. We thank the Cambridge Biotomography Centre and the Natural History Museum, University of Oslo, for use of their CT scanners. All images reconstructed from Natural History Museum specimens are shown courtesy of the Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London. We are grateful to Clifford Sia and Sergei Taraskin for advising us on our methodology. Finally, we would like to thank our three reviewers for their very constructive comments.

Funding

Some of the CT scans were paid for by a grant to MJM from the Department of Physiology, Development & Neuroscience, University of Cambridge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ASB and MJM designed the study. MJM and ØH made the CT scans. LW wrote the software for calculating areas and perimeters. MJM and LW processed the scans and analysed the data. ASB and MJM led the writing of the paper; the other authors contributed to this.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mason, M.J., Wenger, L.M.D., Hammer, Ø. et al. Structure and function of respiratory turbinates in phocid seals. Polar Biol 43, 157–173 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-019-02618-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-019-02618-w