Abstract

Anakinra is a drug that can be administered subcutaneously as a self-injection in both children and adults. We aimed to evaluate the content, reliability, and quality of the videos most viewed on “anakinra self-injection” on YouTube, which is an easily accessible source of information. We performed a YouTube search using the keywords “anakinra”, “anakinra injection”, and “anakinra self-injection” in addition to the generic and commercial names of the biologic agent in September 2021. The quality and reliability of the videos were assessed according to the Global Quality Score (GQS) and DISCERN score. Video power index was used to assess both the view and the like ratio of the videos. A total of 51 videos were analyzed, a majority of which were uploaded by physicians (56.9%). The median GQS was 3 and total DISCERN score was 49. According to the GQS, 21.6% of the videos were of low quality, 35.3% were of fair quality, and 43.1% were of high quality. High-quality videos had higher DISCERN scores and longer duration of videos (p < 0.05). 41 (80.4%) videos were categorized as useful information, and 8 (15.7%) as useful as per patients’ opinion. Further, GQS and DISCERN scores of videos that had useful information were significantly higher. There are numerous YouTube videos with helpful information that can be a source of knowledge on the safe and correct technique of daily anakinra self-injection for both adults and children. There was no significant difference in patient interaction between useful and misleading videos. This indicates that patients do not differentiate between high- and low-quality videos.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anakinra is a human recombinant interleukin (IL)-1 receptor antagonist and the scope of its usage is increasing gradually. It is routinely used in patients with colchicine-resistant idiopathic recurrent pericarditis [1]; undefined autoinflammatory diseases [2]; gout flares, especially in patients who are unresponsive to conventional therapy and/or have contraindications with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, glucocorticoids, and colchicine [3]; and colchicine-resistant familial Mediterranean fever [4]. It has also been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and cryopyrin-associated periodic fever syndrome (5). The European Medicines Agency has approved the use of anakinra for these indications and Still’s disease [both adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD) and systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA)] [5]. Recently, anakinra has also been used in cases of severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by COVID-19 [6, 7].

Anakinra is administered daily as a subcutaneous injection and can be self-administered by patients. The advantages of subcutaneous administration are that the patients can decide where and when to take their medication and don't have to go to a health center daily. However, before self-administration, patients should receive appropriate self-injection training from a healthcare professional to learn the method of administration.

With the use of the internet in the last 20 years, it has become easier for patients to access information about their diseases, and the internet has become a popular research tool [8]. In recent years, with its rich video content, YouTube is generally preferred by everyone as an educational tool and information resource. YouTube is one of the most used online resources to obtain health information [9], and nearly three-quarters of the patients are reported to be influenced by information available from online searches on treatment modalities [10]. However, patients also worry about the reliability of this information .

In previous studies, the quality of anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) and methotrexate (MTX) subcutaneous self-injection videos, which required practical application, were evaluated [11, 12]. Anakinra is a drug that can be administered subcutaneously as a self-injection in both children and adults, and there is no study evaluating anakinra self-injection videos on YouTube in the literature to the best of our knowladge. . Hence, we aimed to evaluate the content, reliability, and quality of the most viewed videos of “anakinra self-injection” on YouTube, which is an easily accessible source of information.

Materials and methods

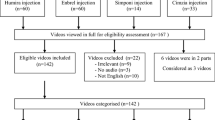

Videos on YouTube (http://www.youtube.com) were searched using the keyword “anakinra”, “anakinra injection”, and “anakinra self-injection” on September 8, 2021. The browser search history was deleted before the study to minimize the effect of past internet use on search results. Video listings were made based on view counts which enables the most viewed videos to be listed on the first page. A total of 85 videos were listed according to “most viewed”. We assessed all videos, and the 85 videos were recorded in a file for future analysis because search results on YouTube constantly change. A total of 51 videos were included in the study after removing duplicate (14 videos), non-English (13 videos), and irrelevant (7 videos) videos found during the YouTube search.

Video features, quality, reliability, and usability analysis

The videos were viewed and analyzed independently by a rheumatologist (MP) and a rheumatology fellow (TID). The properties of the YouTube videos were recorded: titles of videos, length of each video, number of views, number of comments, number of likes and dislikes, duration, upload date, and number of days since upload. Video popularity was evaluated by calculating the like ratio (likes / [likes + dislikes] × 100), view ratio (views/day), and video power index (VPI; like ratio × view ratio/100) [13]. The profiles of the uploaded resources were recorded and divided into five categories: physician, non-physician health personnel, health-related websites, medical company, and patient.

Evaluation of usefulness

-

1.

Useful information (Group 1): These are videos that contain useful and accurate information. The video showed how to use an anakinra syringe and taught self-injection.

-

2.

Misleading information (Group 2): These are videos that contain false information or do not contain information on how to use and self-administer an anakinra injection.

-

3.

Useful patient opinion (Group 3): These videos contain a patient's current or past personal experiences and/or feelings regarding the use of an anakinra syringe. The video showed how to use an anakinra syringe and taught self-injection.

-

4.

Misleading patient opinion (Group 4): Videos that contain false information from a patient or do not contain information on how to use and self-administer an anakinra injection.

Global Quality Scale (GQS) was used for the quality analysis. It is a five-point (1–5) scale that measures the quality, flow, and usefulness of a video. Accordingly, four or five points indicate high quality, three points indicate medium quality, and one or two points indicate low quality [14]. GQS is shown in Supplementary Table S1.

The DISCERN instrument was developed to enable patients and information providers to judge the quality of information. It consists of 15 questions plus an overall quality rating: section 1 : It is composed of three sections evaluating reliability and has eight questions, section 2 : gives quality of information about treatment options and has seven questions, and section 3 : gives general quality of the information and includes an overall rating. Each question was scored on a 5-point (1–5) scale. If the quality criterion was completely fulfilled, a score of 5 was assigned, and if it was not fulfilled at all, a score of 1 was assigned [15]. The total DISCERN score was calculated by summing up the scores for the 15 questions [16]. Accordingly, it can be categorized as very poor (< 27), poor (27–38), fair (39–50), good (51–62), and excellent (63–75) [17, 18].

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 22 was used for the analysis of the data. Shapiro–Wilk test was performed to test the normality of data. Frequency, median, minimum, and maximum were used as descriptive methods. Kruskal–Wallis test was used to determine statistically significant differences between more than two groups of an independent variable. The Spearman test was performed for correlation analysis. The inter-rater agreement was assessed with the kappa coefficient. The results were evaluated at a 95% confidence interval and a significance level of p < 0.05.

Results

A total of 51 videos were analyzed. Video characteristics were summarized in Table 1. Thirteen of the videos' titles are 'how to use', 9 of RA, 8 of COVID-19, 7 of AOSD, 4 of periodic fever syndromes, 3 of hidradenitis suppurativa, 3 of gout, 2 of biological agents, 1 of sJIA, and 1 of uveitis.

A majority of the videos (56.9%) were uploaded by physicians. The median GQS score was 3.0 and DISCERN total score was 49.0. “According to DISCERN classification 9.8% were “very poor”, 13.7% were “poor”, 35.3% were “fair”, 37.3% were “good” and 3.9% were “excellent”. According to GQS score, 21.6% were low quality, 35.3% were fair quality, and 43.1% were high quality. The Cohen kappa score was calculated at 0.897 for the GQS score and 0.836 for the DISCERN total.

Among the total 51 videos, 41 (80.4%) were categorized as useful information, 1 (2.0%) as misleading information, 8 (15.7%) as useful patient opinion, and 1 (2.0%) as misleading patient opinion. Of the videos, 100% (n = 5) produced by non-physician health personnel, 96.6% (n = 28) produced by physicians and 66.7 (n = 4) produced by medical company were of useful information. GQS scores and DISCERN scores were significantly higher in videos which had useful information (Table 2).

GQS and DISCERN quality scores were found to be significantly higher in the physicians’ group than in the patient group when the video features were compared according to the video source (4 (2–5) vs. 2 (1–3) for GOS score and 4 (1–5) vs. 2 (1–4) for DISCERN quality score, respectively). No statistical significance was found in terms of other features of the videos (p > 0.05).

Significant differences were detected between the quality groups in terms of DISCERN scores and duration (sec) (p < 0.05 and p = 0.031, respectively). The highest scores were found in the high-quality group (Table 3).

We detected a positive correlation between GQS score and DISCERN scores. Correlation analyses for GQS score and DISCERN scores were presented in Table 4.

Discussion

The internet contributes significantly to the way people communicate and obtain information. It has been reported that people turn to the internet as the first source of health information, even before obtaining a doctor’s recommendation, regarding medical issues. [19]. With open access and a user-friendly interface, YouTube, while providing free content, may present false information, owing to the lack of an evaluation process in terms of accuracy and timeliness. In addition to various medical branches, the quality and content of YouTube videos for various rheumatological diseases have been examined, and apart from the useful information about rheumatological diseases [20, 21], it was emphasized that misinformation was also present on YouTube [12, 13]. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate YouTube videos on “anakinra self-injection” using validated tools. The videos containing information about “anakinra self-injection” on YouTube were mostly uploaded by physicians. The vast majority of the videos had fair to high quality and reliability. High-quality videos had higher DISCERN scores and longer duration of videos. And also, while the majority of the videos contained useful information, the GQS and DISCERN scores of the videos containing useful information were significantly higher.

In several studies, video sources on YouTube have been classified in different ways. In a study evaluating Botox videos, it was observed that the videos uploaded by health professionals were at the rate of 43% [22], while in another study evaluating fibromyalgia videos, it was reported that the videos were mostly uploaded by physicians (28%) [13]. Similarly, in a study evaluating the quality and validity of spondyloarthritis videos, 62% of the videos were uploaded by healthcare professionals [20]. In another study, YouTube videos about the side effects of biological drugs were evaluated, and it was emphasized that 33.8% of the videos were uploaded by professional organizations and physician groups [23]. Similarly, in this study, 56.9% of the anakinra self-injection videos were uploaded by physicians. Unlike our findings, in a study evaluating Sjögren’s syndrome videos, it was stated that 51.4% of the videos were from independent users [24]. In addition, in studies,MTX and anti-TNF self-injection methods were evaluated, 52.9% and 79.6% of the videos, respectively, were uploaded by patients [11, 12]. It can be thought that this difference may be due to the differences in the usage areas of the drugs, subjective evaluations, and publications from different geographical regions that are conducted at different times.

Previously, many studies have been conducted to evaluate the quality of open-access videos about health information in different branches. In the study of Zengin et al. in which they evaluated the videos on the side effects of biological agents, it was reported that 40.3% of the videos were high quality, 23.4% of intermediate quality and 36.4% of low quality [23]. In another study, 34% of the videos about secukinumab were reported to be of high quality, 32% of intermediate quality, and 34% of low quality [26]. Similarly, in this study, 43.1% of the videos were high quality and 35.3% of fair quality. The median total DISCERN scores and GQS were 49 (23–76) and 3 (1–5), respectively. In contrast, a study conducted by Duran et al. in 2021, videos on testicular cancer were evaluated and 63.2% of the videos were reported to be poor, 26.9% fair, and 9.9% good quality [25]. It was thought that these differences between studies could be due to various video sort . These findings show that the reliability and quality of YouTube videos about anakinra self-injection are satisfactory.

Videos on health information can be uploaded by a wide variety of sources, and in addition to videos containing useful information, videos containing misleading information can also be found. In this study, useful videos made up 80.4% of the total videos regardless of the source. This rate was similar to that reported in previous studies exploring information on RA and anti-TNF self-injection [11, 27]. On the contrary, in a study in which MTX self-injection videos were evaluated, only 19.6% of the videos were found to be useful [12]. These results show that most of YouTube videos about anakinra self-injections are considered useful and of good quality, containing accurate and unbiased information, and can therefore be used to inform patients about the safe and correct technique of anakinra self-injection. While GQS and DISCERN scores are higher in useful videos, there was no significant difference in viewer interaction parameters (number of views and likes per day) for useful videos and misleading videos. Similarly, 51% of the videos about Sjögren’s syndrome and 54.9% of the RA videos were found to be beneficial, albeit with no significant difference in audience interaction between the useful and misleading groups in both studies [24, 27]. This may suggest that the viewers did not have a preference for watching particular types of videos and had difficulty in distinguishing between useful and useless information. This result shows that patients can potentially watch lower-quality videos with false information. As an alternative solution to limit the dissemination of misleading information, physicians or healthcare organizations should upload more medical material containing reliable and accurate information.

For patients to have access to accurate information, it is necessary to ensure that they have access to useful and quality videos. In this study, useful videos were found to have high reliability, comprehensiveness, and quality. In a study in which anti-TNF self-injection training videos were examined, it was stated that 62.5% of the useful videos were from universities/professional organizations/non-profit physician/physician groups and their GQS was 5 (5–5) [11]. Further, 80% of the videos containing useful information about MTX self-injection were uploaded by universities/ professional organizations/non-profit physician/physician groups and their mean (SD) GQS was 4.2 (1.0) [12]. Similar to the literature, physicians were found to be the main source of useful videos in this study, and the GQS and total DISCERN score of useful videos were 4 (2–5) and 54 (24–76), respectively In addition, 2% of the videos in this study were misleading, which was slightly less than the educational videos about other diseases on YouTube. In the literature, 30% of the RA information-containing videos, 27.5% of the MTX self-injection training videos, and 4% of the Botox videos for the treatment of facial wrinkles were misleading [12, 22, 27]. It is thought that these differences between the studies may be due to subjective evaluation of the studies and the fact that these studies were on different subjects and sources.

This study has some limitations such as evaluating only English videos on YouTube. Some other limitations were as follows: subjective evaluation despite the use of validated tools, lack of information about the characteristics of the audience/viewers, and the fact that the study was conducted according to the YouTube settings, which may vary depending on the geographic region and time period.

In conclusion, there are numerous YouTube videos with helpful information that can be a source of information on the safe and correct technique of daily anakinra self-injection used by both adults and children. There was no significant difference in patient interaction between useful and misleading videos. This indicates that patients do not differentiate between high- and low-quality videos. Although internet is a supplementary educational tool for patients, to help ensure the best treatment outcomes, patients should be guided by doctors to sources that provide reliable and accurate information.

References

Brucato A, Imazio M, Gattorno M, Lazaros G, Maestroni S, Carraro M, Finetti M, Cumetti D, Carobbio A, Ruperto N, Marcolongo R, Lorini M, Rimini A, Valenti A, Erre GL, Sormani MP, Belli R, Gaita F, Martini A (2016) Effect of Anakinra on recurrent pericarditis among patients with colchicine resistance and corticosteroid dependence: the AIRTRIP Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 316(18):1906–1912. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.15826

Ter Haar NM, Eijkelboom C, Cantarini L, Papa R, Brogan PA, Kone-Paut I, Modesto C, Hofer M, Iagaru N, Fingerhutová S, Insalaco A, Licciardi F, Uziel Y, Jelusic M, Nikishina I, Nielsen S, Papadopoulou-Alataki E, Olivieri AN, Cimaz R, Susic G, Stanevica V, van Gijn M, Vitale A, Ruperto N, Frenkel J, Gattorno M (2019) Clinical characteristics and genetic analyses of 187 patients with undefined autoinflammatory diseases. Ann Rheum Dis 78(10):1405–1411. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214472

Janssen CA, Oude Voshaar MAH, Vonkeman HE, Jansen T, Janssen M, Kok MR, Radovits B, van Durme C, Baan H, van de Laar M (2019) Anakinra for the treatment of acute gout flares: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, active-comparator, non-inferiority trial. Rheumatology (Oxford). https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/key402

Ben-Zvi I, Kukuy O, Giat E, Pras E, Feld O, Kivity S, Perski O, Bornstein G, Grossman C, Harari G, Lidar M, Livneh A (2017) Anakinra for colchicine-resistant familial mediterranean fever: a randomized, double-blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Arthritis Rheumatol 69(4):854–862. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.39995

Cimaz R, Maioli G, Calabrese G (2020) Current and emerging biologics for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Expert Opin Biol Ther 20(7):725–740

Huet T, Beaussier H, Voisin O, Jouveshomme S, Dauriat G, Lazareth I, Sacco E, Naccache JM, Bézie Y, Laplanche S, Le Berre A, Le Pavec J, Salmeron S, Emmerich J, Mourad JJ, Chatellier G, Hayem G (2020) Anakinra for severe forms of COVID-19: a cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol 2(7):e393–e400. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2665-9913(20)30164-8

Cavalli G, De Luca G, Campochiaro C, Della-Torre E, Ripa M, Canetti D, Oltolini C, Castiglioni B, Tassan Din C, Boffini N, Tomelleri A, Farina N, Ruggeri A, Rovere-Querini P, Di Lucca G, Martinenghi S, Scotti R, Tresoldi M, Ciceri F, Landoni G, Zangrillo A, Scarpellini P, Dagna L (2020) Interleukin-1 blockade with high-dose anakinra in patients with COVID-19, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and hyperinflammation: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol 2(6):e325–e331. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2665-9913(20)30127-2

Amante DJ, Hogan TP, Pagoto SL, English TM, Lapane KL (2015) Access to care and use of the Internet to search for health information: results from the US National Health Interview Survey. J Med Internet Res 17(4):e106. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4126

Li HO, Bailey A, Huynh D, Chan J (2020) YouTube as a source of information on COVID-19: a pandemic of misinformation? BMJ Glob Health. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002604

Madathil KC, Rivera-Rodriguez AJ, Greenstein JS, Gramopadhye AK (2015) Healthcare information on YouTube: a systematic review. Health Inf J 21(3):173–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1460458213512220

Tolu S, Yurdakul OV, Basaran B, Rezvani A (2018) English-language videos on YouTube as a source of information on self-administer subcutaneous anti-tumour necrosis factor agent injections. Rheumatol Int 38(7):1285–1292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-018-4047-8

Rittberg R, Dissanayake T, Katz SJ (2016) A qualitative analysis of methotrexate self-injection education videos on YouTube. Clin Rheumatol 35(5):1329–1333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-015-2910-5

Ozsoy-Unubol T, Alanbay-Yagci E (2021) YouTube as a source of information on fibromyalgia. Int J Rheum Dis 24(2):197–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185x.14043

Bernard A, Langille M, Hughes S, Rose C, Leddin D, Veldhuyzen van Zanten S (2007) A systematic review of patient inflammatory bowel disease information resources on the World Wide Web. Am J Gastroenterol 102(9):2070–2077. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01325.x

Charnock D, Shepperd S, Needham G, Gann R (1999) DISCERN: an instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol Community Health 53(2):105–111. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.53.2.105

Kaicker J, Debono VB, Dang W, Buckley N, Thabane L (2010) Assessment of the quality and variability of health information on chronic pain websites using the DISCERN instrument. BMC Med 8(1):1–8

Weil AG, Bojanowski MW, Jamart J, Gustin T, Lévêque M (2014) Evaluation of the quality of information on the Internet available to patients undergoing cervical spine surgery. World Neurosurg 82(1–2):e31–e39

Som R, Gunawardana N (2012) Internet chemotherapy information is of good quality: assessment with the DISCERN tool. Br J Cancer 107(2):403–403

Hesse BW, Moser RP, Rutten LJ (2010) Surveys of physicians and electronic health information. N Engl J Med 362(9):859–860. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc0909595

Elangovan S, Kwan YH, Fong W (2021) The usefulness and validity of English-language videos on YouTube as an educational resource for spondyloarthritis. Clin Rheumatol 40(4):1567–1573. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05377-w

Kocyigit BF, Nacitarhan V, Koca TT, Berk E (2019) YouTube as a source of patient information for ankylosing spondylitis exercises. Clin Rheumatol 38(6):1747–1751. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-018-04413-0

Wong K, Doong J, Trang T, Joo S, Chien AL (2017) YouTube videos on botulinum Toxin A for wrinkles: a useful resource for patient education. Dermatol Surg 43(12):1466–1473. https://doi.org/10.1097/dss.0000000000001242

Zengin O, Onder ME (2020) YouTube for information about side effects of biologic therapy: a social media analysis. Int J Rheum Dis 23(12):1645–1650. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185x.14003

Delli K, Livas C, Vissink A, Spijkervet FK (2016) Is YouTube useful as a source of information for Sjögren’s syndrome? Oral Dis 22(3):196–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.12404

Duran MB, Kizilkan Y (2021) Quality analysis of testicular cancer videos on YouTube. Andrologia. https://doi.org/10.1111/and.14118

Kocyigit BF, Akaltun MS (2019) Does YouTube provide high quality information? Assessment of secukinumab videos. Rheumatol Int 39(7):1263–1268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-019-04322-8

Singh AG, Singh S, Singh PP (2012) YouTube for information on rheumatoid arthritis—a wakeup call? J Rheumatol 39(5):899–903. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.111114

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have contributed equally to the development of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

Since the study does not include any human participants or animals and the videos were available to everyone, ethics committee approval was not required.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pamukcu, M., Izci Duran, T. Are YouTube videos enough to learn anakinra self-injection?. Rheumatol Int 41, 2125–2131 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-021-04999-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-021-04999-w