Abstract

Purpose

The combination of an mTOR inhibitor with 5-fluorouracil-based anticancer therapy is attractive because of preclinical evidence of synergy between these drugs. According to our phase I study, the combination of capecitabine and everolimus is safe and feasible, with potential activity in pancreatic cancer patients.

Methods

Patients with advanced adenocarcinoma of the pancreas were enrolled. Eligible patients had a WHO performance status 0–2 and adequate hepatic and renal functions. The treatment regimen consisted of capecitabine 1000 mg/m2 BID day 1–14 and everolimus 10 mg daily (5 mg BID) in a continuous 21-day schedule. Tumor assessment was performed with CT-scan every three cycles. Primary endpoint was response rate (RR) according to RECIST 1.0. Secondary endpoints were progression-free survival, overall survival and 1-year survival rate.

Results

In total, 31 patients were enrolled. Median (range) treatment duration with everolimus was 76 days (1–431). Principal grade 3/4 toxicities were hyperglycemia (45 %), hand-foot syndrome (16 %), diarrhea (6 %) and mucositis (3 %). Prominent grade 1/2 toxicities were anemia (81 %), rash (65 %), mucositis (58 %) and fatigue (55 %). RR was 6 %. Ten patients (32 %) had stable disease resulting in a disease control rate of 38 %. Median overall survival was 8.9 months (95 % CI 4.6–13.1). Progression-free survival was 3.6 months (95 % CI 1.9–5.3).

Conclusions

The oral regimen with the combination of capecitabine and everolimus is a moderately active treatment for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, with an acceptable toxicity profile at the applied dose level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The PI3K/Akt pathway is an important intracellular signaling pathway that is often dysregulated in cancer [1]. Signal transduction of activated PI3K/Akt is transmitted through several downstream targets, including the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) [2, 3]. Everolimus, an oral mTOR inhibitor, has demonstrated antitumor properties in vitro and in vivo including inhibition of cell proliferation, cell survival and angiogenesis and showed additive as well as synergistic effects when combined with other anticancer agents such as 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) [4–11].

Single-agent everolimus has been investigated in phase I–III clinical trials in patients with various types of advanced solid tumors [12–19]. These trials demonstrated that treatment with everolimus at 10 mg daily was well tolerated and showed clinical activity in some malignancies with an acceptable toxicity profile, consisting mainly of stomatitis and fatigue.

Clinical trials investigating everolimus in combination with other anticancer drugs have been performed or are ongoing, in short, confirming preclinical evidence that everolimus may be more efficacious when used in combination with other anticancer drugs [20–25]. Recently, a phase II study with the combination of low-dose capecitabine (650 mg/m2 BID day 1–14) and everolimus (5 mg BID) showed effectivity in heavily pretreated gastric cancer patients, and with an acceptable toxicity profile [26]. Previously, we demonstrated the safety and feasibility of the combination of capecitabine 1000 mg/m2 BID day 1–14 and continuous everolimus 5 mg BID in a 21-day schedule [27]. In this phase I study, two out of three patients with pancreatic cancer achieved a partial remission (PR).

In the pre-FOLFIRINOX era, gemcitabine was considered standard therapy for first-line treatment of pancreatic cancer patients, because of a significant improvement of the clinical benefit response, although the survival advantage was <1 month, in comparison with 5-FU [28, 29]. Although studies with the oral 5-FU analogue capecitabine in direct comparison with 5-FU or gemcitabine in patients with pancreatic cancer are not available, capecitabine seems to have comparable activity in this patient group [30].

In the present phase II study, we explored the activity of capecitabine and everolimus combination treatment as first- and second-line therapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer.

Materials and methods

Patient population

Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years, with histologically or cytologically confirmed advanced pancreatic cancer, and measurable lesions according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST 1.0) [31]. Patients who had prior chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting or for metastatic disease were eligible. Adjuvant patients were considered second line if the chemotherapy free interval was <6 months before start study. Other eligibility criteria included WHO performance status ≤2, estimated life expectancy of ≥3 months, adequate bone marrow (white blood cell count ≥ 3.0 × 109/L, platelets ≥ 100 × 109/L) and adequate hepatic and renal function (serum bilirubin ≤ 1.5 × upper limit of normal (ULN), ALAT/ASAT ≤ 2.5 × ULN or in case of liver metastases ≤ 5 × ULN and serum creatinine ≤ 150 μmol/L). Patients were ineligible if they had established alcohol abuse, drug addiction and/or psychotic disorders that made adequate follow-up unlikely. Women who were pregnant or lactating were also excluded. All patients gave written informed consent. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Academic Medical Center Amsterdam and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The trial was registered online (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01079702).

Study design and treatment

This was a phase II, open-label, single-center study to assess the antitumor activity and safety of the combination of everolimus and capecitabine. The primary endpoint was response rate. The study was conducted at the Amsterdam Medical Center, The Netherlands. Everolimus was administered continuously at an oral dose of 5 mg BID. The first 7 days of treatment patients were treated with single-agent everolimus to reach steady-state drug concentrations. Treatment with capecitabine 1000 mg/m2 BID started on day 8 and was given twice daily for 14 days in a three weekly cycle. Toxicity was graded using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 3.0 and was assessed every treatment cycle [32]. Tumor measurements were performed at baseline and every three cycles, and responses were evaluated in accordance with RECIST 1.0 [31]. Patients continued treatment until disease progression, withdrawal of consent or in case of intolerability. Overall survival was defined from start of study treatment until death. Progression-free survival was defined from start of study to clinical or radiological progression or death. When treatment was discontinued due to other reasons, date of last documented assessment was used and censored.

Statistical analysis

For sample size calculations, the two-stage design according to Gehan for estimating the response rate was used [33]. In the first stage, 14 patients were entered. If no responses were observed in the first stage, then the trial would be terminated because the absence of response (0/14) has a probability <0.05 if the true response rate is 0.20. We choose for an estimate with approximately a 10 % standard error, with an accrual of 11 patients in the second stage. For the evaluation of the safety, efficacy parameters descriptive statistics were applied using SPSS statistics. Intention to treat analysis was used.

Results

In total, 31 patients with advanced pancreatic cancer were enrolled between June 2010 and November 2011. After a partial response in the first stage of 14 patients, 11 patients were enrolled in the second stage. Six additional patients were enrolled to ensure 25 patients receiving at least one full cycle of the treatment combination for a complete safety analysis (see below).

Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. The majority of patients had metastatic adenocarcinoma and a WHO performance status of 0–1. The study group consisted of 15 first-line patients and 16 second-line patients. Eighteen patients received prior gemcitabine-based chemotherapy; 11 in palliative setting, six adjuvant (five patients with chemotherapy free interval <6 months) and 1 as part of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy.

Overall, a total of 147 treatment cycles were given, with a median (range) of 3 (1–9) cycles per patient. Median (range) treatment duration with everolimus was 76 (1–431) days (Table 2). Six patients temporarily interrupted treatment with everolimus due to adverse events. Following treatment interruption, five patients received a 50 % dose reduction of everolimus and the other continued treatment at the full dose of everolimus. Due to adverse events, treatment with capecitabine was interrupted in 15 patients resulting in dose reductions for capecitabine in 14 patients.

Safety

Six patients did not receive a complete cycle of the treatment combination; two patients refusal, three patients had early clinical progression, and one patient died of non-treatment-related septic cholangitis. Treatment-related toxicities of these patients were included in the intention to treat toxicity analysis.

Table 3 lists the treatment-related CTC grade 1–2 and grade 3–4 adverse events. The most frequently reported clinical toxicities of any grade included mucositis, skin reactions, fatigue, nausea and diarrhea. Severe clinical toxicities were not frequent. Grade 3–4 hand-foot syndrome was observed in five patients, diarrhea in two patients, stomatitis, skin rash and vomiting in one patient. Three patients developed grade 3 hematological toxicity (thrombocytopenia and anemia). Hyperglycemia of any grade was the most frequently reported biochemical toxicity, resulting in clinical relevance (grade 3) in fourteen patients. Grade 3 levels of alkaline phosphatase, hypokalemia and hyperbilirubinemia occurred in two, five and one patients, respectively.

Antitumor activity

A total of 31 participating patients had measurable disease according to RECIST 1.0 at start of treatment. Nine of these 31 patients were not available for radiological response evaluation due to early discontinuation of the study medication prior to the first planned radiological evaluation time point and were considered as progressive. Two patients had a partial response (6.5 %). Ten patients had stable disease (32 %), and nineteen patients were progressive (61 %) (Table 4).

In first-line patients, PR and SD were seen in 2 (13 %) and 8 (53 %), respectively. In second-line patients, no patients had PR and 2 (13 %) patients had SD. The waterfall plot shows radiologic responses for all radiologic evaluable patients (Fig. 1).

Among the nine patients who discontinued treatment early and who were not available for the first radiological response evaluation, two patients refused further therapy, three patients had clinical progressive disease and one patient developed grade 3 diarrhea and had deterioration of the performance status. Three patients died before radiological evaluation, two patients due to tumor progression and one patient died of non-treatment-related septic cholangitis during the first cycle

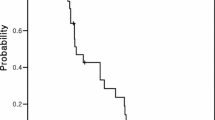

At the time of the intention to treat analysis, one patient was still alive. For the entire cohort, the one-year survival rate was 38.7 % and the median overall survival was 8.9 months (95 % CI 4.6–13.1 months) (Fig. 2). Overall survival was 12.4 months (95 % CI 10.2–14.6) and 5.9 months (95 % CI 1.6–10.2) in first (n = 15)- and second-line patients (n = 16), respectively. Median progression-free survival (PFS) was 3.6 months (95 % CI 1.9–5.3), 5.7 months (95 % CI 2.0–9.5) and 2.3 months (95 % CI 2.2–2.5) for all, first- and second-line patients, respectively.

Discussion

In this phase II study, exploring the combination of capecitabine with the oral mTOR inhibitor everolimus in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer moderate treatment activity was observed with a response rate (RR) of 6.5 % and an overall survival (OS) of 8.9 months.

As a single-arm phase II study, the contribution of everolimus in this treatment regimen is difficult to determine. However, our results can be compared with previous studies using capecitabine as monotherapy. A RR of 7.1 % was seen in a study of capecitabine (1250 mg/m2 BID) in 42 patients with advanced pancreatic cancer as first-line treatment [30]. A randomized phase II study with pre-treated pancreatic cancer patients showed a RR of 9.4 % for the 32 patients in the capecitabine (1250 mg/m2 BID) control arm [34].

The endpoint OS in non-randomized phase II studies, should be used with care, because of the constraints of historical control groups and inadequate sample sizes, especially in subgroup analyses. Nevertheless, the median OS of 8.9 months in the entire cohort, 12.4 months in first-line patients and 5.9 months in second-line patients reported in this study are encouraging. The overall survival for capecitabine monotherapy in first-line patients reported by Cartwright et al. [30] was 5.9 months (95 % CI 2.8–9.0 months). And OS in second-line patients, reported by Bodoky et al. [34] was 5.0 months. Therefore, the addition of everolimus to capecitabine might enhance efficacy of capecitabine monotherapy, especially in first-line patients.

The most commonly reported treatment-related clinical side effects were stomatitis, fatigue and hand-foot syndrome. Although stomatitis is a common adverse event of both capecitabine and everolimus as single agent, this overlapping toxicity remained mild to moderate in severity in this study and led to dose reduction in only one patient. We assume at most marginally additive toxicity of capecitabine to everolimus since the frequency of stomatitis in this study was similar to that in studies with single-agent everolimus [30, 34, 35]. The frequency of fatigue was increased compared with single-agent studies of either agent, suggesting an additive toxic effect of the combination. An alternative explanation for the increased incidence of fatigue might be disease related. Patients with pancreatic cancer have a high probability to develop disease-related fatigue [36]. Hand-foot syndrome can be solely attributed to capecitabine, since this has not been observed before in single-agent everolimus trials. This well-known side effect of capecitabine resulted in dose reductions of capecitabine in 45 % of the patients, which is only 10 % higher than in a previous study with colorectal cancer patients receiving capecitabine monotherapy and might be related to the combinatory effects of the study drugs [37]. Grade 3 hyperglycemia was seen in 45 % of the patients in the non-fasting blood draws, which is more than seen in everolimus monotherapy in this patient group (18 %), but it mostly remained at manageable levels and did not lead to dose reductions [14]. Other adverse events included diarrhea, anorexia, taste loss, neuropathy and skin rash, but remained non-severe. The frequency and severity of toxicity confirmed the data from our previous phase I study [27].

In contrast to the outlined acceptable toxicity findings, a prior phase I study that combined the mTOR inhibitor temsirolimus and 5-FU demonstrated dose limiting stomatitis and hematological toxicity, and in the expansion cohort, two patients died due to mucositis with bowel perforation [38]. An explanation for this difference could be dose related. The dose of temsirolimus in the expansion cohort of that phase I study was 45 mg/m2 per week, while the recommended dose used as monotherapy in renal cell carcinoma is 25 mg per week. The phase II study of capecitabine (650 mg/m2 BID) and everolimus (5 mg BID) in gastric cancer patients, showed less toxicity, especially in all grade hand-foot syndrome (35 vs 13 %), fatigue (55 vs 6 %) and diarrhea (48 vs 22 %) [26]. This is probably due to the lower dose of capecitabine and the different disease.

Recently, the combination of conventional chemotherapy (gemcitabine) with everolimus is examined as first-line treatment for pancreatic cancer patients [39]. Everolimus 5 mg BID could not be combined with full-dose gemcitabine, as the maximum tolerated dose was already met at 400 mg/m2 [39]. In comparison with the present study, this might indicate that for combining everolimus with conventional chemotherapy, capecitabine is easier to administer at therapeutical doses.

In conclusion, we showed that continuous everolimus 5 mg BID combined with capecitabine 1000 mg/m2 for 14 days every 3 weeks is a feasible and moderately efficacious outpatient oral treatment regimen, but only in first-line pancreatic cancer patients.

References

Faivre S, Kroemer G, Raymond E (2006) Current development of mTOR inhibitors as anticancer agents. Nat Rev Drug Discov 5(8):671–688

LoPiccolo J, Blumenthal GM, Bernstein WB, Dennis PA (2008) Targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway: effective combinations and clinical considerations. Drug Resist Updat 11(1–2):32–50

Aoki M, Blazek E, Vogt PK (2001) A role of the kinase mTOR in cellular transformation induced by the oncoproteins P3k and Akt. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98(1):136–141

Matsuzaki T, Yashiro M, Kaizaki R, Yasuda K, Doi Y, Sawada T et al (2009) Synergistic antiproliferative effect of mTOR inhibitors in combination with 5-fluorouracil in scirrhous gastric cancer. Cancer Sci 100(12):2402–2410

Bu X, Le C, Jia F, Guo X, Zhang L, Zhang B et al (2008) Synergistic effect of mTOR inhibitor rapamycin and fluorouracil in inducing apoptosis and cell senescence in hepatocarcinoma cells. Cancer Biol Ther 7(3):392–396

Seeliger H, Guba M, Koehl GE, Doenecke A, Steinbauer M, Bruns CJ et al (2004) Blockage of 2-deoxy-D-ribose-induced angiogenesis with rapamycin counteracts a thymidine phosphorylase-based escape mechanism available for colon cancer under 5-fluorouracil therapy. Clin Cancer Res 10(5):1843–1852

Beuvink I, Boulay A, Fumagalli S, Zilbermann F, Ruetz S, O’Reilly T et al (2005) The mTOR inhibitor RAD001 sensitizes tumor cells to DNA-damaged induced apoptosis through inhibition of p21 translation. Cell 120(6):747–759

Seeliger H, Guba M, Kleespies A, Jauch KW, Bruns CJ (2007) Role of mTOR in solid tumor systems: a therapeutical target against primary tumor growth, metastases, and angiogenesis. Cancer Metastasis Rev 26(3–4):611–621

Mabuchi S, Altomare DA, Cheung M, Zhang L, Poulikakos PI, Hensley HH et al (2007) RAD001 inhibits human ovarian cancer cell proliferation, enhances cisplatin-induced apoptosis, and prolongs survival in an ovarian cancer model. Clin Cancer Res 13(14):4261–4270

Khariwala SS, Kjaergaard J, Lorenz R, Van Lente F, Shu S, Strome M (2006) Everolimus (RAD) inhibits in vivo growth of murine squamous cell carcinoma (SCC VII). Laryngoscope 116(5):814–820

Zitzmann K, De Toni EN, Brand S, Goke B, Meinecke J, Spottl G et al (2007) The novel mTOR inhibitor RAD001 (everolimus) induces antiproliferative effects in human pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor cells. Neuroendocrinology 85(1):54–60

Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, Hutson TE, Porta C, Bracarda S et al (2008) Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Lancet 372(9637):449–456

Amato RJ, Jac J, Giessinger S, Saxena S, Willis JP (2009) A phase 2 study with a daily regimen of the oral mTOR inhibitor RAD001 (everolimus) in patients with metastatic clear cell renal cell cancer. Cancer 115(11):2438–2446

Wolpin BM, Hezel AF, Abrams T, Blaszkowsky LS, Meyerhardt JA, Chan JA et al (2009) Oral mTOR inhibitor everolimus in patients with gemcitabine-refractory metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 27(2):193–198

Ellard SL, Clemons M, Gelmon KA, Norris B, Kennecke H, Chia S et al (2009) Randomized phase II study comparing two schedules of everolimus in patients with recurrent/metastatic breast cancer: NCIC Clinical Trials Group IND.163. J Clin Oncol 27(27):4536–4541

Soria JC, Shepherd FA, Douillard JY, Wolf J, Giaccone G, Crino L et al (2009) Efficacy of everolimus (RAD001) in patients with advanced NSCLC previously treated with chemotherapy alone or with chemotherapy and EGFR inhibitors. Ann Oncol 20(10):1674–1681

O’Donnell A, Faivre S, Burris HA III, Rea D, Papadimitrakopoulou V, Shand N et al (2008) Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the oral mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor everolimus in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 26(10):1588–1595

Okamoto I, Doi T, Ohtsu A, Miyazaki M, Tsuya A, Kurei K et al (2010) Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of RAD001 (everolimus) administered daily to Japanese patients with advanced solid tumors. Jpn J Clin Oncol 40(1):17–23

Tabernero J, Rojo F, Calvo E, Burris H, Judson I, Hazell K et al (2008) Dose- and schedule-dependent inhibition of the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway with everolimus: a phase I tumor pharmacodynamic study in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 26(10):1603–1610

Campone M, Levy V, Bourbouloux E, Berton Rigaud D, Bootle D, Dutreix C et al (2009) Safety and pharmacokinetics of paclitaxel and the oral mTOR inhibitor everolimus in advanced solid tumours. Br J Cancer 100(2):315–321

Andre F, Campone M, O’Regan R, Manlius C, Massacesi C, Sahmoud T et al (2010) Phase I study of everolimus plus weekly paclitaxel and trastuzumab in patients with metastatic breast cancer pretreated with trastuzumab. J Clin Oncol 28(34):5110–5115

Pacey S, Rea D, Steven N, et al (2004) Results of a phase 1 clinical trial investigation a combination of the oral mTOR-inhibitor Everolimus (E, RAD001) and Gemcitabine (GEM) in patients (pts) with advanced cancers. In: Abstract ASCO annual meeting 2004, J Clin Oncol 22 (Suppl. 14):3120

Milton DT, Riely GJ, Azzoli CG, Gomez JE, Heelan RT, Kris MG et al (2007) Phase 1 trial of everolimus and gefitinib in patients with advanced nonsmall-cell lung cancer. Cancer 110(3):599–605

Hainsworth JD, Infante JR, Spigel DR, Peyton JD, Thompson DS, Lane CM et al (2010) Bevacizumab and everolimus in the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma: a phase 2 trial of the Sarah Cannon Oncology Research Consortium. Cancer 116(17):4122–4129

Baselga J, Semiglazov V, van Dam P, Manikhas A, Bellet M, Mayordomo J et al (2009) Phase II randomized study of neoadjuvant everolimus plus letrozole compared with placebo plus letrozole in patients with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 27(16):2630–2637

Lee SJ, Lee J, Lee J, Park SH, Park JO, Park YS et al (2013) Phase II trial of capecitabine and everolimus (RAD001) combination in refractory gastric cancer patients. Invest New Drugs 31(6):1580–1586

Deenen MJ, Klumpen HJ, Richel DJ, Sparidans RW, Weterman MJ, Beijnen JH et al (2011) Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of capecitabine and the oral mTOR inhibitor everolimus in patients with advanced solid malignancies. Invest New Drugs 30(4):1557–1565

Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouché O, Guimbaud R et al (2011) FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 364(19):1817–1825

Burris HA 3rd, Moore MJ, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML et al (1997) Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 15(6):2403–2413

Cartwright TH, Cohn A, Varkey JA, Chen YM, Szatrowski TP, Cox JV et al (2002) Phase II study of oral capecitabine in patients with advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 20(1):160–164

Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L et al (2000) New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst 92(3):205–216

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v3.0 (CTCAE). http://ctep.cancer.gov/reporting/ctc_v30.html

Gehan EA (1961) The determination of the number of patients required in a preliminary and a follow-up trial of a new chemotherapeutic agent. J Chronic Dis. 13:346–353

Bodoky G, Timcheva C, Spigel DR, La Stella PJ, Ciuleanu TE, Pover G et al (2011) A phase II open-label randomized study to assess the efficacy and safety of selumetinib (AZD6244 [ARRY-142886]) versus capecitabine in patients with advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer who have failed first-line gemcitabine therapy. Invest New Drugs 30(3):1216–1223

Yao JC, Shah MH, Ito T, Bohas CL, Wolin EM, Van CE et al (2011) Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med 364(6):514–523

Labori KJ, Hjermstad MJ, Wester T, Buanes T, Loge JH (2006) Symptom profiles and palliative care in advanced pancreatic cancer: a prospective study. Support Care Cancer 14(11):1126–1133

Cassidy J, Twelves C, Van CE, Hoff P, Bajetta E, Boyer M et al (2002) First-line oral capecitabine therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: a favorable safety profile compared with intravenous 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin. Ann Oncol 13(4):566–575

Punt CJ, Boni J, Bruntsch U, Peters M, Thielert C (2003) Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of CCI-779, a novel cytostatic cell-cycle inhibitor, in combination with 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin in patients with advanced solid tumors. Ann Oncol 14(6):931–937

Joka M, Boeck S, Zech CJ, Seufferlein T, Wichert GV et al (2014) Combination of antiangiogenic therapy using the mTOR-inhibitor everolimus and low-dose chemotherapy for locally advanced and/or metastatic pancreatic cancer: a dose-finding study. Anticancer Drugs 25(9):1095–1101

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Academic Medical Center Amsterdam. Everolimus was supplied free of charge by Novartis.

Conflict of interest

H.J. Klumpen declares to currently conduct research which is sponsored by Novartis, the manufacturer of everolimus. All other authors declare no conflict of interest. Novartis had no role in the study design, the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

S. Kordes and H. J. Klümpen have contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kordes, S., Klümpen, H.J., Weterman, M.J. et al. Phase II study of capecitabine and the oral mTOR inhibitor everolimus in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 75, 1135–1141 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-015-2730-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-015-2730-y