Abstract

Data on efficacy and safety of azacitidine in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with >30 % bone marrow (BM) blasts are limited, and the drug can only be used off-label in these patients. We previously reported on the efficacy and safety of azacitidine in 155 AML patients treated within the Austrian Azacitidine Registry (clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT01595295). We herein update this report with a population almost twice as large (n = 302). This cohort included 172 patients with >30 % BM blasts; 93 % would have been excluded from the pivotal AZA-001 trial (which led to European Medicines Agency (EMA) approval of azacitidine for high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and AML with 20–30 % BM blasts). Despite this much more unfavorable profile, results are encouraging: overall response rate was 48 % in the total cohort and 72 % in patients evaluable according to MDS-IWG-2006 response criteria, respectively. Median OS was 9.6 (95 % CI 8.53–10.7) months. A clinically relevant OS benefit was observed with any form of disease stabilization (marrow stable disease (8.1 months), hematologic improvement (HI) (9.7 months), or the combination thereof (18.9 months)), as compared to patients without response and/or without disease stabilization (3.2 months). Age, white blood cell count, and BM blast count at start of therapy did not influence OS. The baseline factors LDH >225 U/l, ECOG ≥2, comorbidities ≥3, monosomal karyotype, and prior disease-modifying drugs, as well as the response-related factors hematologic improvement and further deepening of response after first response, were significant independent predictors of OS in multivariate analysis. Azacitidine seems effective in WHO-AML, including patients with >30 % BM blasts (currently off-label use). Although currently not regarded as standard form of response assessment in AML, disease stabilization and/or HI should be considered sufficient response to continue treatment with azacitidine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is an aggressive disease with an unfavorable prognosis [1, 2]. Treatment with curative potential, i.e., conventional chemotherapy and/or allogeneic stem cell transplantation, is rarely an option for elderly patients due to high age, comorbidities, poor performance status, and/or adverse cytogenetics. Azacitidine is approved for AML with 20–30 % bone marrow (BM) blasts. Approval was based on the pivotal AZA-001 trial [3, 4]. Currently, the 001-follow-up trial (clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT01074047) is underway with the same design, but limited to patients with >30 % BM blasts, with the aim to widen the indication of azacitidine to AML patients as defined by WHO, i.e., irrespective of BM blast count. Until the results of this trial become available, treatment of AML patients with more than 30 % BM blasts with azacitidine remains an off-label use.

We previously reported on the use, efficacy, and safety of azacitidine in 155 WHO-AML patients treated in a real-life setting. We herein update this report with a population almost twice as large (n = 302). The aim of the current publication was to potentially confirm, consolidate, and validate our previous results. The primary endpoint was evaluation of efficacy (i.e., response) of azacitidine in patients with AML defined according to WHO criteria (including patients with >30 % BM blasts). The secondary endpoints were safety (i.e., toxicity and adverse events), overall survival (OS), and statistical analysis of factors known or thought to influence overall survival in order to establish prognostic markers (Table 1 [4–14]).

Patients, design, and methods

Between February 2009 and October 2013, 302 AML patients from 14 specialized centers for hematology and medical oncology in Austria were included. Data cleaning/survival analysis cutoff date was 21 January 2014. The sole inclusion criteria were the diagnosis of WHO-AML and treatment with at least one dose of azacitidine. No formal exclusion criteria existed, as the aim was to include all AML patients treated with azacitidine, irrespective of age, comorbidities, and/or number of previous lines of treatment. Informed consent to allow the collection of personal data was obtained for all retrospectively documented patients who were alive, as well as for all prospectively included patients.

Registry design, data collection and monitoring, as well as assessment of efficacy, safety and endpoints within the Austrian Azacitidine Registry were performed as previously described [8, 15].

Overall response was defined as complete response (CR), marrow complete response (mCR), partial response (PR) (as defined by commonly used AML response criteria [16]), and hematologic improvement (HI) (as defined by the IWG-MDS-2006 response criteria [17]). Marrow stable disease (mSD) was defined as failure to achieve at least PR, but no evidence of progressive disease (PD) for >8 weeks. PD was defined as any of the following: (i) ≥50 % decrement from maximum remission/response in granulocytes or platelets, (ii) reduction in hemoglobin by 2 g/dl, (iii) transfusion dependence [17].

OS was assessed using the Kaplan–Meier method. Univariate analyses were performed with log-rank tests. Cox regression stratified on the various factors was used for analyses of risk factors for OS. Baseline characteristics were compared by nonparametric tests (Chi-squared test for qualitative variables, Wilcoxon test for quantitative variables). For multivariate analysis, logistic regression according to the Wald method with forward stepwise selection (entry level 0.05; level for keeping the variable 0.051) was used. Univariate analyses were performed and confirmed by two independent statisticians [H.A., O.E.]. The confirmed results were the basis for multivariate analysis. All variables with p < 0.05 in univariate analyses were included in multivariate analysis, except for those cases, where parsimony would have been disrupted due to redundancy in the variables. Analyses were performed with SPSS. No adjustments were made for multiple testing.

Results

Patient characteristics

Patient baseline characteristics at azacitidine treatment start can be taken from Table 2. Median age was 73 (range 30–93); 43 % of patients were older than 75, 21 % were older than 80, and 8 % were older than 85 years, respectively; 172 patients (57 %) had >30 % BM blasts; 19 % had an unfavorable karyotype, and 67 % had an intermediate karyotype according to MRC criteria [18]. In the absence of consensus for cytogenetic classification of AML in the elderly [4, 19], we additionally assessed the IPSS cytogenetic risk categories [20] (Table 2).

Treatment modalities

Azacitidine was administered as first-line treatment in 46 % of patients; 46 % of patients received azacitidine after insufficient response to, or early relapse after, conventional chemotherapy/allo-SCT (32 %), or other disease modifying treatment (14 %); the remaining patients received azacitidine either as bridging to allogeneic stem cell transplantation (allo-SCT) (3 %) or as maintenance treatment after CR to chemotherapy (4 %). Azacitidine was not always first-line therapy, but also second-, third-, fourth-, fifth-, or last-line therapy for a relevant proportion of our patients: 28 % had received more than one line of conventional chemotherapy prior to azacitidine (Table 2).

A median number of 4 (range 1–37) azacitidine courses were given. Most patients (85 %) received the drug subcutaneously (average dose/cycle, 846 mg), 10 % intravenously (average dose/cycle, 815 mg), and in 5 % both applications forms were used (average dose/cycle, 831 mg); 77 % of patients predominantly received 7 days of azacitidine (53 % European Medicines Agency (EMA)-approved d1-7 (median dose/cycle, 924 mg), 24 % 5-2-2 (median dose/cycle, 910 mg)) (Supplemental Table 1). EMA-approved azacitidine target dose (75 mg/m2 × 7 ± 10 %) was reached in 33 % of applied cycles; 349/2013 (17 %) of all cycles were administered as “flat” dosage (i.e., 100 mg azacitidine/cycle-day; median dose/cycle, 700 mg). Hospitalization for the sole reason of azacitidine application occurred in 47 % of cycles at the discretion of the treating physician, mainly due to concerns with frailty and potential toxicity, and due to logistic reasons for patients living far away from the hospital. Azacitidine treatment dose was modified during treatment in 18 % of patients: dose reductions occurred due to an adverse event (15 %) or due to patient’s/physicians wish (2 %); dose escalation was performed in 1 % of patients. Dose reductions were performed in 32 % of responding patients (prior to best response (13 %), at best response (3 %), or after best response (15 %)).

Concomitant treatment and best supportive care measures

Erythropoietin-stimulating agents (ESA) (2.4 %), iron chelation treatment (ICT) (2.3 %), and G-CSF (18.4 %) were given in parallel to azacitidine when deemed necessary by the treating physician.

Response

Overall response, defined as CR, mCR, PR, and HI, was documented in 48 % of the total intention-to-treat (ITT) cohort and in 72 % of patients evaluable according to MDS-IWG-2006 response criteria [17] (i.e., had received >2 cycles of azacitidine); HI was documented in 40 % (ITT) and 72 % (evaluable according to IWG, i.e., had received >2 cycles of azacitidine), respectively; CR/mCR was achieved in 17 % of the ITT cohort and in 28 % of patients in whom a BM aspirate/biopsy was performed (Supplemental Table 2).

The median number of cycles received by responding patients was 8.5 (range 1–37), and 2 (range 1–28) in non-responders (included patients with SD). Of note, the distribution of applied schedules as well as the median and mean azacitidine dosages/cycle did not differ between responders and non-responders.

Time to response and response deepening

Median time to first response was 3.0 months. First response occurred after 3, 4, and 5 cycles in 58, 79, and 88 % of responding patients, respectively, but could be observed as late as cycle 16 in patients with stable disease who were kept on therapy. First response was best response in 99/144 patients (69 %). Median response duration was 3.4 (range 0.3–33.0) months. Further deepening of response after first response (i.e., achievement of BM blast reduction in terms of mCR/CR/PR after HI) was seen in 45/144 (31 %) of responders. Best response was reached by cycle 9 in 94 %, but could be observed as late as cycle 21. Median time from first to best response was 3.5 (range 0.8–21.5) months.

Toxicity and adverse events

A total of 1.031 adverse events (AE) were documented in 2.013 azacitidine cycles. Overall, 24 % of all AE and 20 % of grade 3–4 (G3-4) AE were attributed to azacitidine (Supplemental Table 3). Of all AE, 22 % resulted in hospitalization and 9 % resulted in death. Most AE had no consequence for azacitidine treatment (66 %). Dose reduction (5 %), treatment pause (11 %), prolongation of azacitidine cycle duration >28 days (7 %), and/or termination of azacitidine treatment (11 %) were not commonly necessary.

G3-4 hematologic toxicity occurred in 48 %: G3-4 neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia were documented in 35, 30, and 28 % of patients, respectively; clinically relevant bleeding events were noted in 12 % of patients (Table 3). Non-hematologic toxicity was usually mild, the most common AE being fatigue (39 %), gastrointestinal (38 %), unspecified pain (30 %), and injection site reactions (22 %). Infectious complications of any grade were documented in 63 %, febrile neutropenia in 19 % (Table 3). G3-4 infectious events occurred in 33 % and were dominated by pulmonary infections, sepsis, and fever of unknown origin. Hospital admission was required in 173/423 (41 %) and transfer to an intensive care unit was necessary in 3 % of total infectious events. Treatment with G-CSF, antibiotics, antifungals, and/or virostatics occurred in 18, 86, 22, and 14 %, respectively.

A total of 47 non-hematologic G3-4 events occurred in 33 patients (11 %): 39 (83 %) of these grade 3–4 events occurred in the cardiac system: left ventricular output failure (n = 23), arrhythmia (n = 7), hypertension (n = 5), myocardial infarction (n = 3), angina pectoris (n = 1). In 20/33 (61 %) patients experiencing cardiac G3-4 events, pre-existing coronary artery disease, reduced cardiac function, arrhythmias, and/or valvular heart disease were documented prior to azacitidine treatment and worsening was not thought to be azacitidine-related.

Overall survival and potential prognostic parameters

Median OS was 9.6 (95 % CI 8.53–10.7) months as from initiation of treatment with azacitidine in the entire cohort. Median progression-free survival in responding patients was 9.1 (0.9–39.9) months. Progression defining events were death due to any reason, disease progression, disease relapse after response, and/or new cytogenetic aberration/clonal evolution. Median OS was 16.1 months for responders (defined as CR/mCR/PR/HI) and 3.7 months for non-responders. Median time from first diagnosis to treatment start with azacitidine for untreated (n = 139) versus pre-treated with disease-modifying treatment (n = 163) patients was 0.6 and 7.1 months, respectively. Median time from azacitidine treatment stop to death was 1.9 months in the entire cohort. Reasons for cessation of azacitidine in patients receiving ≤2 cycles of azacitidine (n = 101, 33.4 %) were death (n = 48), disease progression (n = 20), patient’s wish (n = 9), toxicity or recurrent infectious complications (n = 5), allo-SCT (n = 2), and others (n = 13); 41/101 receiving ≤2 cycles died within 1 month of treatment termination, and a further 35 died within 6 months.

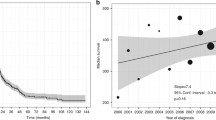

In line with our previous results [8], the following baseline factors did not significantly affect overall survival: gender, age </≥75, age </≥80, WHO-AML-type, WBC count </≥10 G/l, WBC count </≥15 G/l, WBC count </≥30 G/l, neutrophil count <1,000/μl, lymphocyte count <2,000/μl, RBC-TD, BM blast count ≤30/>30 % (irrespective of whether the whole cohort or only patients treated with azacitidine first line were analyzed), serum erythropoietin level, as well as prior treatment with ESA, G-CSF, iron chelators, low-dose Ara-C, or hydroxyurea (Supplemental Table 4 and Fig. 1a–h). When looking at responding patients only, WHO-AML type, WBC count, and treatment according to EMA label had no significant effect on survival (Supplemental Table 4).

Kaplan–Meier curves of baseline factors that did not affect overall survival (OS). a Effect of bone marrow blast count on OS (total cohort). b Effect of bone marrow blast count on OS (AZA first line). c Effect of age on OS. d Effect of WHO-AML type on OS. e Effect of white blood cell (WBC) count on OS. f Effect of WBC </≥15 G/l on OS. g Effect of achievement of EMA/FDA-target dose on OS. h Effect of azacitidine (AZA) schedule: 5 vs. 7 days of azacitidine per cycle on OS

Time-dependent factors that did not affect overall survival include the following: EMA target dose (p = 0.213), treatment schedule, dose/cycle, and platelet-doubling after one cycle (Supplemental Table 4). The following toxicity and adverse events-related factors had no effect on overall survival: bleeding events, febrile neutropenia, surgery, non-hematologic toxicity, falls, and pain due to any reason (Supplemental Tables 1 and 4).

In multivariate analysis, the following baseline factors remained independent adverse predictors for OS: LDH >225 U/l, ECOG ≥2, number of comorbidities (as predefined by the HCT-CI [21]) >3, and monosomal karyotype. The following treatment-related factors that remained independent predictors for OS in multivariate analysis were as follows: AZA first-line treatment, hematologic improvement, and further deepening of response after first response; best marrow response (p = 0.642) did not meet the 0.05 significance level for inclusion in the multivariate analysis; azacitidine pause due to adverse events was associated with longer OS in multivariate analysis; dose reduction due to adverse events (p = 0.051) and fatigue limiting self-care (p = 0.053) were borderline significant in multivariate analysis (Figs. 2 and 3, and Supplemental Table 5).

Kaplan–Meier curves of baseline factors that significantly affected overall survival (OS) in multivariate analysis. a Effect of monosomal karyotype (MK) on OS. b Effect of MK in comparison to complex karyotype on OS. c Effect of prior disease-modifying treatment (i.e., azacitidine first-line no vs. yes) on OS. d Effect of hematologic improvement (HI) on OS. e Effect of response deepening (i.e., achievement of BM blast reduction in terms of mCR/CR/PR after HI) on OS. f Overall survival by best response

Discussion

This is the largest so far published number of azacitidine-treated WHO-AML patients, with the highest per capita coverage of AML patients in a nationwide registry, suggesting limited selection (Table 1, Supplemental Table 7). Data on the efficacy of azacitidine in AML with >30 % BM blasts are limited, and the drug can only be used off-label in these patients (Table 1 [4–14]). We report on 302 WHO-AML patients treated with azacitidine. This cohort included 172 patients with >30 % BM blasts (Tables 1 and 4 [6–8, 12, 14]). The number of AML diagnoses per year, as well as the number of AML patients included in the respective year for Austria in general and Salzburg in particular, is presented in Supplemental Table 7 (data obtained from Statistics Austria (personal communication 23 May 2014), and Tumor Registry Salzburg (personal communication 26 May 2014)).

In order to exclude a potential time-dependent bias regarding both the choice of AML patients for treatment with azacitidine, as well as inclusion in the Austrian Azacitidine Registry, we compared all relevant baseline characteristics, treatment modalities, as well as response rates, and the occurrence of adverse events of our previously published cohort (n = 155; data cutoff 21 January 2012) [8] with the current cohort (n = 302, data cut off 21 January 2014). No significant difference could be found for any of these characteristics (Supplemental Table 6). With this nearly twice as large cohort, we confirm and validate the safety and efficacy of azacitidine in WHO-AML patients treated in a real-life setting. The observed median OS of 9.6 months and the high overall response rates (48 % ITT) seem remarkable, particularly since (i) the registry included many elderly (43 % ≥75 years), comorbid (79 %), and/or pretreated patients (62 %); (ii) 33 % of patients received ≤2 cycles of azacitidine (reasons therefore listed in the “Results” section); (iii) 82 % of our registry population would have been excluded from the AZA-001 registration trial due to an estimated life expectancy <3 months, ECOG >2, t-AML, prior treatment, or planned allo-SCT [3, 4]. If BM blast count >30 % is also taken into account, 93 % would have been excluded.

Furthermore, virtually all of our prior results [8] regarding the statistical value of various factors on OS are confirmed by the present analysis. Slight discrepancies are mentioned below and in Table 4. In addition to the parameters looked at previously, we analyzed the putative prognostic effect of platelet-doubling after cycle 1, monosomal karyotype, and disease stabilization, as these factors have emerged to be of interest only recently [12, 13, 22].

This is the first report to analyze the effect of platelet-doubling after cycle 1 on OS in AML patients treated with azacitidine. Statistical significance was not observed (Supplemental Table 4).

We confirm the recently introduced monosomal karyotype (MK) [23] to be the strongest adverse cytogenetic predictor for OS (even outperforming the categories “complex karyotype” and “MDS-related cytogenetic abnormalities” [22–24]) (Figs. 2 and 3a–b, Supplemental Table 5). We extend these findings to the new WHO classification and show that azacitidine cannot overcome the adverse outcome conferred by the presence of MK. Outcome in patients with MK is not only dismal with azacitidine but also with induction therapy and/or allogeneic stem cell transplantation [22]. Therefore, clinical trials are urgently needed for this patient subgroup.

We confirm our previous results [8] that a certain amount of aplasia induction seems necessary before response occurs, and that further deepening of response after first response (i.e., achievement of BM blast reduction in terms of mCR/CR/PR after HI) translates into significantly longer OS (21.4 months), compared with patients for whom first response was best response (12.6 months) (Figs. 2 and 3e, Supplemental Table 5). This underlines the importance of continuing azacitidine treatment if or when HI occurs, even in the absence of marrow response. Patients experiencing HI had significantly longer OS than those who did not (16.1 vs. 4.5 months) (Fig. 3d and Supplemental Table 5). This is the first report to separately analyze HI and marrow response in multivariate analysis. The former remained an independent prognostic factor for OS in multivariate analysis, whereas the latter did not (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Table 5). This seems of clinical relevance, as hematologic improvement is not generally considered sufficient response in AML patients. Very recently, the French group reported no survival benefit for patients achieving HI in addition to stable disease [12]. However, the authors state that (i) only those patients not achieving mCR/CR/PR were analyzed for HI; (ii) HI was only assessed when patients were evaluable for these parameters; (iii) it is not stated how many patients were not evaluable for HI or how SD was defined (i.e., marrow SD or hematologic SD). In our cohort, OS was significantly better for patients achieving mCR/CR/PR with HI (20.5 months), followed by mSD with HI (18.9 months), mCR/CR/PR without HI (15.0 months), HI without mSD (9.7 months), mSD without HI (8.1 months), and not unexpectedly, OS was worst for patients with progressive disease or who received less than 3 cycles of azacitidine (3.2 months) (Supplemental Table 5). We thus confirm and extend the observations of the French group [12] as follows: It seems that achievement of any form of disease stabilization, be it mSD or HI alone, and especially the combination thereof (without the requirement of concomitant BM blast reduction, but with the minimal requirement of mSD), is sufficient to confer a clinically relevant OS benefit. In our opinion and clinical experience, we thus consider disease stabilization to be sufficient “response” to continue treatment with azacitidine, although we are aware of the fact that this is currently not regarded as a standard form of response assessment in AML (Fig. 3f). In our experience, disease stabilization is lost rapidly once treatment with azacitidine is stopped (median time to death, 1.9 months). Thus bearing the lack of therapeutic alternatives in mind, we continue azacitidine treatment until overt clinical disease progression.

In order to facilitate the comparison of our previous and current results with data obtained from much smaller cohorts, we provide an in-depth comparison of all published multivariate analyses on putative prognostic factors for OS of WHO-AML patients treated with azacitidine (including results from the present study) (Table 4). Only one baseline factor remained a significant adverse predictor for OS in all multivariate analysis (4/4) in which baseline factors were analyzed, namely ECOG/WHO performance score (Table 4). Thus, the ability of patients to function in everyday life seems to be the most important predictor of OS in elderly AML patients treated with azacitidine. In line with this, the absolute number of comorbidities, which was borderline significant in our previously published smaller cohort of AML patients (n = 155) [8], was confirmed to be an independent adverse predictor of OS in our larger present cohort (n = 302) (Fig. 2, Table 4, and Supplemental Table 5).

Although not unexpected, we show for the first time in multivariate analysis—thus confirming our clinical experience and notion—that prior disease-modifying treatment is an adverse predictor of OS for AML patients treated with azacitidine. In multivariate analysis, patients receiving azacitidine first line had significantly longer overall survival than pretreated patients (12.9 vs. 7.5 months) (Figs. 2 and 3c, Supplemental Table 5).

Age, gender, AML type, and transfusion dependence prior to azacitidine had no significant effect on OS in all reports in which these factors were analyzed (Table 4, Supplemental Table 4, and Fig. 1c, d). As azacitidine is still not approved for the treatment of AML patients with >30 % BM blasts, we were particularly interested to see that the percentage of BM blasts had no significant effect on OS in this off-label treated patient subgroup (n = 172), which is in line with observations by others with smaller patient numbers (Fig. 1a, b, Table 4, and Supplemental Table 4).

The present report confirms that WHO-AML type does not seem to adversely predict OS. We conclude that AML patients with MDS-related features, or therapy-related AML, should not be precluded from treatment with azacitidine. The latter seems clinically relevant, especially in light of the fact that these AML subgroups are generally considered to have worse prognosis and to be less responsive to conventional chemotherapy.

The prognostic relevance of elevated WBC ≥15 G/l currently remains unclear and conflicting results exist (Table 4). Several statistical issues remain open in the two publications describing a significant adverse effect of WBC ≥15 G/l on OS in multivariate analysis: (i) in the Dutch cohort, this variable was not significant in univariate analysis (p = 0.11), but was nevertheless included in multivariate analysis. Furthermore, 95 % CI were not given for multivariate results [14]; (ii) the univariate p values used for entry of the variables into the multivariate model (p < 0.15 [14] and p < 0.85 [25], respectively) were less stringent than in the present publication (p < 0.05), which could not find an adverse effect of elevated WBC, irrespective of which cutoff value was used (</≥10, </≥15, or </≥30 G/l (Supplemental Table 4 and Fig. 1e, f)).

Neither azacitidine schedule (5 vs. 7 days) nor dosage (<vs. = 75 mg/m2/day) had a significant effect on OS in 3/3 reports in which these factors were analyzed (Table 4, Supplemental Table 4, and Fig. 1g, h). Thus, alternative schedules and dosages seem safe and without loss of efficacy, and receiving the drug regularly and continuously until overt clinical progression occurs is likely more relevant than the absolute dosage per day or number of days per cycle.

In conclusion, we confirm that azacitidine is safe and effective in elderly, comorbid AML patients treated in an everyday life setting, irrespective of BM blast count.

References

Lowenberg B (2001) Prognostic factors in acute myeloid leukaemia. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 14(1):65–75

Stone RM (2002) The difficult problem of acute myeloid leukemia in the older adult. CA Cancer J Clin 52(6):363–371

Fenaux P, Mufti GJ, Hellstrom-Lindberg E, Santini V, Finelli C, Giagounidis A et al (2009) Efficacy of azacitidine compared with that of conventional care regimens in the treatment of higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes: a randomised, open-label, phase III study. Lancet Oncol 10(3):223–232

Fenaux P, Mufti GJ, Hellstrom-Lindberg E, Santini V, Gattermann N, Germing U et al (2010) Azacitidine prolongs overall survival compared with conventional care regimens in elderly patients with low bone marrow blast count acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 28(4):562–569

Al Ali HK, Jaekel N, Junghanss C, Maschmeyer G, Krahl R, Cross M et al (2012) Azacitidine in patients with acute myeloid leukemia medically unfit for or resistant to chemotherapy: a multicenter phase I/II study. Leuk Lymphoma 53(1):110–117

Gavillet M, Noetzli J, Blum S, Duchosal MA, Spertini O, Lambert JF (2012) Transfusion independence and survival in patients with acute myeloid leukemia treated with 5-azacytidine. Haematologica 97(12):1929–1931

Maurillo L, Venditti A, Spagnoli A, Gaidano G, Ferrero D, Oliva E et al (2012) Azacitidine for the treatment of patients with acute myeloid leukemia: report of 82 patients enrolled in an Italian compassionate program. Cancer 118(4):1014–1022

Pleyer L, Stauder R, Burgstaller S, Schreder M, Tinchon C, Pfeilstocker M et al (2013) Azacitidine in patients with WHO-defined AML—results of 155 patients from the Austrian Azacitidine Registry of the AGMT-Study Group. J Hematol Oncol 6(1):32

Silverman LR, McKenzie DR, Peterson BL, Holland JF, Backstrom JT, Beach CL et al (2006) Further analysis of trials with azacitidine in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome: studies 8421, 8921, and 9221 by the Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Clin Oncol 24(24):3895–3903

Sudan N, Rossetti JM, Shadduck RK, Latsko J, Lech JA, Kaplan RB et al (2006) Treatment of acute myelogenous leukemia with outpatient azacitidine. Cancer 107(8):1839–1843

Thepot S, Itzykson R, Seegers V, Raffoux E, Quesnel B, Chait Y et al (2010) Treatment of progression of Philadelphia negative myeloproliferative neoplasms to myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myeloid leukemia by azacitidine: a report on 54 cases on the behalf of the Groupe Francophone des Myelodysplasies. Blood 116(19):3735–3742

Thepot S, Itzykson R, Seegers V, Recher C, Raffoux E, Quesnel B et al (2014) Azacitidine in untreated acute myeloid leukemia. A report on 149 patients. Am J Hematol 89(4):410–416

van der Helm LH, Alhan C, Wijermans PW, van Marwijk KM, Schaafsma R, Biemond BJ et al (2011) Platelet doubling after the first azacitidine cycle is a promising predictor for response in myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia (CMML) and acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) patients in the Dutch azacitidine compassionate named patient programme. Br J Haematol 155(5):599–606

van der Helm LH, Veeger NJ, Kooy M, Beeker A, de Weerdt O, de Groot M et al (2013) Azacitidine results in comparable outcome in newly diagnosed AML patients with more or less than 30 % bone marrow blasts. Leuk Res 37(8):877–882

Pleyer L, Germing U, Sperr WR, Linkesch W, Burgstaller S, Stauder R et al (2014) Azacitidine in CMML: matched-pair analyses of daily-life patients reveal modest effects on clinical course and survival. Leuk Res 38(4):475–483

Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Kopecky KJ, Buchner T, Willman CL, Estey EH et al (2003) Revised recommendations of the International Working Group for diagnosis, standardization of response criteria, treatment outcomes, and reporting standards for therapeutic trials in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 21(24):4642–4649

Cheson BD, Greenberg PL, Bennett JM, Lowenberg B, Wijermans PW, Nimer SD et al (2006) Clinical application and proposal for modification of the International Working Group (IWG) response criteria in myelodysplasia. Blood 108(2):419–425

Grimwade D, Walker H, Oliver F, Wheatley K, Harrison C, Harrison G et al (1998) The importance of diagnostic cytogenetics on outcome in AML: analysis of 1,612 patients entered into the MRC AML 10 trial. The Medical Research Council Adult and Children’s Leukaemia Working Parties. Blood 92(7):2322–2333

Dombret H, Raffoux E, Gardin C (2008) Acute myeloid leukemia in the elderly. Semin Oncol 35(4):430–438

Greenberg P, Cox C, LeBeau MM, Fenaux P, Morel P, Sanz G et al (1997) International scoring system for evaluating prognosis in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 89(6):2079–2088

Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, Baron F, Sandmaier BM, Maloney DG et al (2005) Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood 106(8):2912–2919

Kayser S, Zucknick M, Dohner K, Krauter J, Kohne CH, Horst HA et al (2012) Monosomal karyotype in adult acute myeloid leukemia: prognostic impact and outcome after different treatment strategies. Blood 119(2):551–558

Breems DA, Van Putten WL, De Greef GE, Zelderen-Bhola SL, Gerssen-Schoorl KB, Mellink CH et al (2008) Monosomal karyotype in acute myeloid leukemia: a better indicator of poor prognosis than a complex karyotype. J Clin Oncol 26(29):4791–4797

Breems DA, Lowenberg B (2011) Acute myeloid leukemia with monosomal karyotype at the far end of the unfavorable prognostic spectrum. Haematologica 96(4):491–493

Thepot S (2009) IRSVRCQBDJCTeal. Azacytidine (AZA) as first line therapy in AML: results of the French ATU Program. Blood 114(22):843

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Gudrun Placher-Sorko, Paracelsus Medical University Salzburg, and Martina Mitrovic, Innsbruck Medical University, for helping with data entry in the eCRF. We would also like to thank Andrew Brittain, from the Knowledgepoint360 Group for the correct formatting of the figures. He had no influence on planning, writing, or interpreting the manuscript.

Funding

The AAR is a Registry of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Medikamentöse Tumortherapie’ (AGMT) Study Group which served as the responsible sponsor and holds the full and exclusive rights on data. Financial support for the AGMT was received from Celgene. Celgene had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

Consultant or advisory role: LP, Celgene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis; WS, Celgene; SB, Celgene; MP, Celgene, Novartis; MG, Mundipharma; AL, Celgene; RS, Celgene; RG, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Cephalon, Celgene.

Honoraria: LP, Celgene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, AOP Orphan Pharmaceuticals; WS, Celgene, Novartis; SB, Mundipharma, Novartis, AOP Orphan Pharmaceuticals; MP, Celgene, Novartis, Janssen-Cilag; MG, Pfizer, Mundipharma; RS, Ratiopharm, Celgene; RG, Amgen, Eisai, Mundipharma, Merck, Janssen-Cilag, Genentech, Novartis, Astra-Zeneca, Cephalon, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Pfizer, Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi Aventis.

Research funding: MG, Pfizer; RS, Ratiopharm, Novartis, Celgene; WS, Phadia; RG, GSK, Amgen, Genentech, Ratiopharm, Celgene, Pfizer, Mundipharma, Cephalon.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplemental Table 1

(DOCX 23 kb)

Supplemental Table 2

(DOCX 24 kb)

Supplemental Table 3

(DOCX 22 kb)

Supplemental Table 4

(DOCX 30 kb)

Supplemental Table 5

(DOCX 36 kb)

Supplemental Table 6

(DOCX 37 kb)

Supplemental Table 7

(DOCX 24 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Pleyer, L., Burgstaller, S., Girschikofsky, M. et al. Azacitidine in 302 patients with WHO-defined acute myeloid leukemia: results from the Austrian Azacitidine Registry of the AGMT-Study Group. Ann Hematol 93, 1825–1838 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-014-2126-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-014-2126-9