Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to determine the incidence, risk factors, and spontaneous recovery rate of vocal fold paresis (VFP) with routine laryngoscopy before and after thyroid surgery.

Methods

All consecutive patients undergoing primary or redo thyroid surgery between years 2011–2016 were prospectively registered in an electronic database, and scheduled for pre- and postoperative laryngoscopic vocal fold inspection by otolaryngologists independently of the surgical team.

Results

A total of 920 thyroid operations with 1296 nerves at risk were performed in 866 patients. Pre- and postoperative laryngoscopy was done in 95% and 98%, respectively. Preoperative VFP was detected in 24 (2.8%) patients. New postoperative VFP was found in 53 of 920 operations (5.8%) and in 55 of 1296 nerves at risk (4.2%). After 12 months, 14 had recovered full vocal fold function and eight had near-complete recovery. VFP was permanent after 29 operations (3.2%); two patients were lost to follow-up with uncertain outcome. Of the 1296 nerves at risk, injury was permanent in 30 (2.3%). In multivariate analysis, patients operated for recurrent goiter had nearly nine times higher risk of new VFP (23% rate), whereas patients with malignant histology had three times higher risk of postoperative VFP (up to 22% rate).

Conclusion

VFP continues to be a serious complication of thyroid surgery, especially in operations for redo goiter and thyroid malignancy. The incidence of VFP may be underestimated unless laryngoscopic examinations are performed routinely.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Vocal fold paresis (VFP) caused by recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) injury is a well-known complication of thyroid surgery, and it has been widely documented in the literature. However, a systematic review by Jeannon and colleagues demonstrated a high variation in screening methods and VFP rates between previously published studies. The rates of transient VFP ranged from 1.4 to 38.4% (mean 9.8%) and from zero to 18.6% (mean 2.3%) for permanent VFP [1]. The incidence of VFP may be underestimated unless routine vocal fold evaluation is performed. In a study involving 26 Scandinavian hospitals with 3660 registered thyroid operations, those institutions that practiced routine postoperative laryngoscopy reported almost two times higher rates of VFP than those that did not [2].

Postoperative RLN injury is considered permanent if complete vocal fold immobility or dysfunction lasts more than 1 year [3]. Permanent injuries have been documented in up to 1.4% and transient injuries in 5.2–12.6% of the patients according to studies which utilized routine postoperative vocal fold examination [4, 5]. The reported risk factors for intraoperative RLN injury include patient’s older age, intrathoracic goiter, thyrotoxicosis, thyroid malignancy, previous thyroidectomy, reoperation for bleeding, extended surgery, low or medium volume hospital, and low-volume surgeons [2, 5,6,7,8].

The primary aim of this study was to prospectively assess the prevalence of incidental preoperative VFP and the incidence rate of perioperative RLN injury using routine laryngoscopy screening before and after thyroid surgery. The secondary aims were to identify risk factors for VFP and to analyze the outcome of postoperative VFP during 12-month follow-up.

Materials and Methods

Study Patients

This was an observational single-institution study based on prospectively collected data. The local ethics committee approved this study, and patient informed consent was not required. All consecutive patients who underwent primary or redo thyroid surgery between January 2011 and December 2016 were prospectively registered in an electronic database as part of a surgical quality initiative in an effort to improve patient care. The follow-up data for the final analysis were collected retrospectively up to 12 months postoperatively.

All patients referred for elective surgical evaluation underwent clinical examination, thyroid ultrasound, and fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy when appropriate. The indications for surgery were registered as primary goiter, recurrent goiter (previous thyroid surgery), suspicious thyroid nodule, malignant thyroid nodule, completion thyroidectomy, hyperthyroidism, or other indication. “Suspicious thyroid nodule” was defined as follicular neoplasm or clinical suspicion for malignancy (based on size, appearance, or growth rate in ultrasound imaging) when the FNA biopsy was inconclusive [9]. Patients with suspicious thyroid nodule underwent hemithyroidectomy. Second-stage completion thyroidectomy was performed if the removed thyroid nodule proved to be malignant. Indication for surgery was defined as “malignant thyroid nodule” when preoperative FNA biopsy was clearly malignant according to the Bethesda system [10]. Postoperative hypocalcemia was defined as serum ionized calcium below 1.16 mmol/L for more than 2 days postoperatively requiring medication and/or prolonged hospital stay. Low-volume surgeon was defined as an operator performing less than 20 cases a year.

Vocal Fold Evaluation and Follow-Up

All patients underwent independent evaluation of vocal fold functioning by otolaryngologists who were not involved in the surgical procedure. An indirect and/or fiberoptic laryngoscopy was performed routinely before and after surgery. Fiberoptic laryngoscopy was used in cases when the visibility in indirect laryngoscopy was inadequate or suboptimal. The postoperative laryngoscopy was performed prior to discharge. “New VFP” was defined as postoperatively diagnosed new-onset VFP that was not detected in the preoperative examination. Patients with VFP were scheduled for 1-month follow-up visit and then followed for approximately 1 year postoperatively or until spontaneous recovery of vocal fold function occurred. “Complete recovery” of postoperative VFP was determined as full recovery of normal vocal fold function documented in laryngoscopic examination. “Near-complete recovery” of VFP was defined as return of vocal fold function after postoperative palsy with no symptoms and only minimal residual dysfunction in the laryngoscopic examination. In case of insufficient follow-up data, the natural outcome of VFP was defined uncertain unless major RLN injury had been verified during the operation.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 24.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Fisher’s exact test or Pearson’s Chi-squared test was used to compare nominal data. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed on independent variables to identify risk factors for postoperative VFP using logistic regression and step-down models. Odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was used to reflect the odds of a new postoperative VFP. Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate VFP recovery rate during 12-month follow-up. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

During the 6-year study period, 920 thyroid operations were performed in 866 patients (mean age 55 ± 16 years, 82% female) with 1296 nerves at risk (Table 1). Preoperative and postoperative laryngoscopy was performed in 95% and 98% of the cases, respectively. Preoperatively, 24 patients (2.8%) had VFP prior to the index operation; 14 were symptomatic. Six had undergone previous ipsilateral thyroid operation, which was the probable cause of the injury. Eight patients with preoperative VFP had malignant thyroid nodule on the same side as the paresis, whereas ten patients had no known cause for the incidental preoperative VFP and thus were considered idiopathic. Nineteen of the preoperative VFPs persisted, and five resolved during the follow-up after surgery.

Postoperatively, new unilateral VFP was detected after 51 operations. Two patients suffered from new bilateral VFP after surgery; one operation was performed due to recurrent goiter and the indication was hyperthyroidism in the other. Two out of the 51 patients with new unilateral VFP had contralateral VFP preoperatively and therefore bilateral VFP postoperatively. The rates of new VFP were 5.8% (n = 53/920) per operations and 4.2% (n = 55/1296) per nerves at risk.

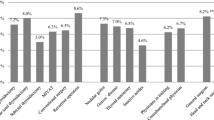

The indications for surgery with corresponding rates of VFP and malignant pathology findings are presented in Table 2. The rates of new VFP and definitive permanent VFP were 5.2% and 2.9% for primary goiter, 22.5% and 15.0% for recurrent goiter, 3.7% and 1.8% for operations performed due to suspicious thyroid nodule, 20.5% and 12.8% for operations with FNA biopsy verified malignancy, and 4.1% and 0.8% for thyroidectomies due to hyperthyroidism, respectively. Malignant histology was found in 172 (19%) of all 920 surgical pathology specimens. Unexpected malignancies were found in 39/383 (10%) operations performed for symptomatic goiter. Malignant neoplasms were confirmed in 73/271 (27%) cases operated for suspicious or undetermined thyroid nodule. Moreover, 17 additional malignancies were found in 56 completion thyroidectomies (30% incidence rate for completion procedures). When FNA biopsy revealed a high suspicion of malignancy, the postoperative histologic examination confirmed carcinoma in 97% of cases (one proved to be a follicular adenoma).

Risk Factors for Postoperative VFP

The univariate analysis of risk factors for new VFP showed that recurrent goiter and FNA biopsy verified malignant thyroid nodule were prominent preoperative predictors of RLN injury during surgery (Table 3). Other operation-related risk factors for RLN injury were total thyroidectomy, concomitant lymph node dissection, and sternotomy. Regarding postoperative variables, hypocalcemia, malignant histology, and especially invasive T3–T4 disease were associated with injuries. During operation, the surgeon identified 722 (56%) out of the 1296 nerves at risk. If the RLN was identified as intact, that correlated negatively with risk of injury, whereas notification of a possible injury had a strong correlation with VFP. One fifth of the procedures were performed by low-volume surgeons with experience of less than 20 cases per year (ranging from 1 to 10 cases per year). Surgeons with higher volume performed 20–35 operations per year. However, there was no statistically significant difference in the VFP rates between low- and high-volume surgeons, 7.1% versus 5.4% (P = 0.387).

In multivariate analysis, significant risk factors for VFP were total thyroidectomy, recurrent goiter, drain usage, and malignant histology in the final pathology examination (Table 4). Eighteen patients (34%) with new VFP had a known risk factor for RLN injury before undergoing surgery (such as previous neck surgery, retrosternal goiter, or extensive surgery requiring sternotomy or thoracotomy). RLN was sacrificed deliberately in three cases to ensure radical dissection of a malignant tumor, and the RLN was dissected sharply from a tumor in six cases with new VFP.

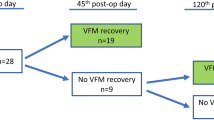

Natural Outcome of Postoperative VFP

Of the 53 patients (mean age 61 ± 15 years) with new postoperative VFP, 42 (79%) were female. Forty-six patients (87%) with new VFP were initially symptomatic. Complete recovery of VFP was documented with laryngoscopic examination in 14 of the 53 patients during the follow-up. Near-complete recovery was clinically and visually documented in four patients. In addition, four patients canceled their follow-up appointment because they were completely asymptomatic and were also defined as “near-complete recovery.” VFP was determined definitively as permanent in 29 patients and 30 nerves at risk; one patient had new permanent bilateral VFP. Two patients were lost to follow-up before 6 months, and thus, their state of recovery was uncertain. For this reason, the numbers of permanent VFP were estimated between 29 and 31 (3.2–3.4%) in 920 thyroid operations and between 30 and 32 (2.3–2.5%) in 1296 nerves at risk. Consequently, the estimated complete recovery rate at 12 months was 34 ± 8%, and 47 ± 8% when near-complete recoveries were included. The majority of recoveries occurred during the first 4 months, and no improvement happened after 12 months (Fig. 1). Two-thirds of all patients with new VFP received active voice therapy. Three patients underwent injection laryngoplasty with calcium hydroxylapatite.

Discussion

Although well known and widely reported in the literature, the incidence of VFP before and after thyroid surgery is exceptionally varying. An important feature of the present study was that the decision to screen for VFP did not rely on the patient’s or surgeon’s judgment. Instead, nearly all cases were examined independently by third-party investigators (otolaryngologists) with 95% preoperative and 98% postoperative laryngoscopic screening coverage.

Lang and colleagues argued against routine preoperative laryngoscopic examination based on their findings in 302 patients undergoing nerve function assessment before thyroid surgery [11]. In their series, the prevalence of preoperative VFP was 2.3% and only one of the patients (0.4%) had not undergone previous thyroid surgery. Similarly in our study, the preoperative rate of VFP was 2.8%; however, in ten cases (1.1% of all patients), the etiology was idiopathic. In our practice, the reasons to perform preoperative laryngoscopy are (1) to register, in case of postoperative VFP, if it was indeed new and caused by the index procedure and (2), in case of preoperative VFP, to be aware of the risk of bilateral VFP after surgery. We had two patients with previous unilateral VFP who suffered from bilateral palsy after surgery. In both cases, the indication for the procedure was recurrent goiter and the preoperative VFP was caused by the primary procedure. Fortunately, in both cases, these new palsies were transient.

According to our results, the incidence of new VFP was 53 in 920 (5.8%) operations and 55 in 1296 (4.2%) nerves at risk. Compared to the results of previous studies in which routine laryngoscopy was used [4, 5], our complication rate was lower (5.8% against 7.6–13.9%). On the other hand, we observed much higher rate of permanent VFP than was demonstrated in these previous studies (3.2–3.4% against 0.9–1.4%). In our study, less than half of VFPs were transient in comparison with approximately 80%–90% in the other studies [4, 5]. These remarkable differences need to be analyzed focusing, for example, on patient’s characteristics, diagnoses, extent of surgical procedures, reporting standards, and hospital and surgeon volumes. In hospitals reporting low permanent VFP rates, operations were usually performed by one experienced surgical team. Our institution is a university clinic and teaching hospital, and consequently, many operations were done by surgeons in training. It is very important for any institution that performs thyroid surgery to acknowledge their RLN injury rates accurately, and the institutional risk must be discussed with the patient when weighing between surgery and surveillance. Patients need to be well informed of the rates of complications at the institution rather than giving the patients only vague estimates of the risks based on the literature. Although only a small proportion of patients with VFP were asymptomatic in our study (13%), postoperative VFP may be easily overlooked unless routine vocal fold examination is implemented to the surgical quality control regime [2].

The routine visualization of RLN is regarded as a gold standard for nerve injury prevention [12]. In our study, the rate of RLN identification was only 56%. Interestingly, we found no difference in VFP rates in cases where RLN was visualized compared to cases where RLN was not seen. Even so, the visualization of an intact RLN during operation correlated to normal VFP function postoperatively. The evidence on routine RLN visualization relies on cases series such as the recent publication by Dhillon and colleagues from Johns Hopkins Hospital which included 2527 nerves at risk with routine RLN evaluation by the operating surgeon in all cases; the reported rates of temporary VFP (2.9%) and permanent VFP (0.4%) per nerves at risk were significantly lower than in our study [13]. However, their study had a mixed cohort including parathyroid procedures, whereas redo procedures were not included; the postoperative VFP rate was 72/2153 nerves at risk (3.3%) in primary thyroid procedures compared to 55/1296 (4.2%) in our study with both primary and redo procedures. Furthermore, Dhillon’s study represents the vast experience of a single high-volume surgeon from one of the world’s most renowned hospitals, whereas our study is a “real-world” representation of small hospital outcomes. During our study period, intraoperative neuromonitoring was not used. Although it is widely recommended in special situations like redo surgery, according to two meta-analyses with 23,500 and 9000 pooled patients, routine use of neuromonitoring was not shown to decrease VFP rates [12, 14]. Considering the high rate of permanent VFP in our study, we modified our technique after this study to include neuromonitoring and we recommend routine identification of the RLN.

The present study confirmed that recurrent goiter is one of the most significant risk factors for postoperative VFP with nearly nine times higher risk than in all other indications combined. Previously, patients with benign recurrent goiter were shown to have 4.7 times higher risk of permanent VFP in a multi-institutional study with 16 448 procedures [6]. While this risk is well identified in the literature, it may still be underestimated in clinical work. The benefits of redo surgery must be carefully weighed against the high risk of RLN injury.

Other risk factors for RLN injury in this study were total thyroidectomy, sternotomy, lymph node dissection, hypocalcemia, and drain use. In total thyroidectomy, both RLNs were at risk, and therefore, the risk was at least twofold compared to hemithyroidectomy. Sternotomy, lymph node dissections, hypocalcemia, and drain use (in only 6% of operations) were all related to extensive surgery and, hence, to increased risk of RLN injury. The drain use itself has not been identified as a risk factor for VFP in a meta-analysis with 1927 patients [15]. In that study, drain was used more liberally, in 51% of patients. Our study was performed at a time when the use of energy devices (i.e., electronic sealing instruments) had been adapted to routine practice (used in 99% of all cases). The effect of energy devices in RLN injury rate could not be assessed because there were not enough cases for the control group; only a few patients were operated without any vessel sealing instrument.

Almost identically to a previous meta-analysis of 1798 patient, two-thirds of the patients with VFP in our study received voice therapy, whereas only 5.7% underwent injection laryngoplasty [16]. Early voice therapy in patients with unilateral VFP has been associated with better outcomes than late rehabilitation in one 11-year retrospective study with 171 patients [17]. Routine postoperative laryngoscopy enables early diagnosis and thus initiation of voice therapy without delay, which is also important in the prevention of aspiration-related problems. Furthermore, routine vocal fold screening gives direct feedback to the surgeon and may help avoid RLN injuries in the future.

Study Limitations

Although this observational study was performed prospectively, the follow-up was not structurized and the follow-up data were extracted in a retrospective fashion. A few patients with VFP declined 12-month follow-up, and therefore, the Kaplan–Meier method with data censoring was used to estimate the recovery rate. It was not clearly defined whether the RLN was identified before or after removal of the thyroid lobe. Therefore, the results regarding RLN identification should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusions

This study highlights the significance of routine screening of VFP in thyroid surgery. Almost 3% of patients had incidental VFP preoperatively, which can only be verified with routinely performed preoperative laryngoscopy. The risk of postoperative new-onset VFP was highest among patients with recurrent goiter and thyroid malignancy (especially stages T3–4). These patient groups need to be well informed of the increased risk before surgery. Less than half of VFPs resolved completely spontaneously, which was a markedly lower rate than previously reported.

References

Jeannon JP, Orabi AA, Bruch GA, Abdalsalam HA, Simo R (2009) Diagnosis of recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy after thyroidectomy: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract 63:624–629

Bergenfelz A, Jansson S, Kristoffersson A et al (2008) Complications to thyroid surgery: results as reported in a database from a multicenter audit comprising 3,660 patients. Langenbecks Arch Surg 393:667–673

Stager SV (2014) Vocal fold paresis: etiology, clinical diagnosis and clinical management. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 22:444–449

Lo CY, Kwok KF, Yuen PW (2000) A prospective evaluation of recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis during thyroidectomy. Arch Surg 135:204–207

Joliat GR, Guarnero V, Demartines N, Schweizer V, Matter M (2017) Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury after thyroid and parathyroid surgery: incidence and postoperative evolution assessment. Medicine (Baltimore) 96:e6674

Dralle H, Sekulla C, Haerting J et al (2004) Risk factors of paralysis and functional outcome after recurrent laryngeal nerve monitoring in thyroid surgery. Surgery 136:1310–1322

Erbil Y, Barbaros U, Issever H et al (2007) Predictive factors for recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy and hypoparathyroidism after thyroid surgery. Clin Otolaryngol 32:32–37

Enomoto K, Uchino S, Watanabe S, Enomoto Y, Noguchi S (2014) Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy during surgery for benign thyroid diseases: risk factors and outcome analysis. Surgery 155:522–528

Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC et al (2016) 2015 American thyroid association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the American Thyroid Association guidelines task force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid 26:1–133

Cibas ES, Ali SZ (2009) The bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology. Thyroid 19:1159–1165

Lang BH, Chu KK, Tsang RK, Wong KP, Wong BY (2014) Evaluating the incidence, clinical significance and predictors for vocal cord palsy and incidental laryngopharyngeal conditions before elective thyroidectomy: Is there a case for routine laryngoscopic examination? World J Surg 38:385–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-013-2259-3

Pisanu A, Porceddu G, Podda M, Cois A, Uccheddu A (2014) Systematic review with meta-analysis of studies comparing intraoperative neuromonitoring of recurrent laryngeal nerves versus visualization alone during thyroidectomy. J Surg Res 188:152–161

Dhillon VK, Rettig E, Noureldine SI et al (2018) The incidence of vocal fold motion impairment after primary thyroid and parathyroid surgery for a single high-volume academic surgeon determined by pre- and immediate post-operative fiberoptic laryngoscopy. Int J Surg 56:73–78

Yang S, Zhou L, Lu Z, Ma B, Ji Q, Wang Y (2017) Systematic review with meta-analysis of intraoperative neuromonitoring during thyroidectomy. Int J Surg 39:104–113

Tian J, Li L, Liu P, Wang X (2017) Comparison of drain versus no-drain thyroidectomy: a meta-analysis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 274:567–577

Chen X, Wan P, Yu Y et al (2014) Types and timing of therapy for vocal fold paresis/paralysis after thyroidectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Voice 28:799–808

Mattioli F, Menichetti M, Bergamini G et al (2015) Results of early versus intermediate or delayed voice therapy in patients with unilateral vocal fold paralysis: our experience in 171 patients. J Voice 29:455–458

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Eastern Finland (UEF) including Kuopio University Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Heikkinen, M., Mäkinen, K., Penttilä, E. et al. Incidence, Risk Factors, and Natural Outcome of Vocal Fold Paresis in 920 Thyroid Operations with Routine Pre- and Postoperative Laryngoscopic Evaluation. World J Surg 43, 2228–2234 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-019-05021-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-019-05021-y