Abstract

Background

Virtual reality (VR) training in minimal invasive surgery (MIS) is feasible in surgical residency and beneficial for the performance of MIS by surgical trainees. Research on stress-coping of surgical trainees indicates the additional impact of soft skills on VR performance in the surgical curriculum. The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of structured VR training and soft skills on VR performance of trainees.

Method

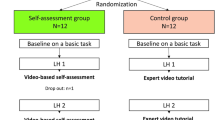

The study was designed as a single-center randomized controlled trial. Fifty first-year surgical residents with limited experience in MIS (“camera navigation” in laparoscopic cholecystectomy only) were randomized for either 3 months of VR training or no training. Basic VR performance and defined soft skills (self-efficacy, stress-coping, and motivation) were assessed prior to randomization using basic modules of the VR simulator LapSim® and standardized psychological questionnaires. Three months after randomization VR performance was reassessed. Outcome measurement was based on the results derived from the most complex of the basic VR modules (“diathermy cutting”) as the primary end point. A correlation analysis of the VR end-point performance and the psychological scores was done in both groups.

Results

Structured VR training enhanced VR performance of surgical trainees. An additional correlation to high motivational states (P < 0.05) was found. Low levels of self-efficacy and negative stress-coping were related to poor VR performance in the untrained control group (P < 0.05). This correlation was absent in the trained intervention group (P > 0.05).

Conclusion

Low self-efficacy and negative stress-coping strategies seem to predict poor VR performance. However, structured training along with high motivational states is likely to balance out this impairment.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lehmann KS, Ritz JP, Maass H, Cakmak HK, Kuehnapfel UG, Germer CT, Bretthauer G, Buhr HJ (2005) A prospective randomized study to test the transfer of basic psychomotor skills from virtual reality to physical reality in a comparable training setting. Ann Surg 241:442–449

Aggarwal R, Grantcharov TP, Eriksen JR, Blirup D, Kristiansen VB, Funch-Jensen P, Darzi A (2006) An evidence-based virtual reality training program for novice laparoscopic surgeons. Ann Surg 244:310–314

Bogner M (1994) Human error in medicine. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ

Gawandee AA, Zinner MJ, Studdert DM, Brennan TA (2003) Analysis of errors reported by surgeons at three teaching hospitals. Surgery 133:614–621

Maschuw K, Osei-Aygemang T, Weyers P, Danila R, Bin Dayne K, Rothmund M, Hassan I (2008) The impact of self-belief on laparoscopic performance of novices and experienced surgeons. World J Surg 32(9):1911–1916

Hassan I, Weyers P, Maschuw K, Dick B, Gerdes B, Rothmund M, Zielke A (2006) Negative stress-coping strategies among novices in surgery correlate with poor virtual laparoscopic performance. Br J Surg 91(12):1554–1559

Flin R (2008) Safety in health care: Research on safety is happening. BMJ 336:171

Yule S, Flin R, Peterson-Brown S, Maran N (2006) Non-technical skills for surgeons in the operating room: a review of the literature. Surgery 139:140–149

Glavin RJ, Maran NJ (2003) Integrating human factors into the medical curriculum. Med Educ 37:59–64

Schwarzer R, Jerusalem M (1995) Generalized self-efficacy scale. In: Weinmann J, Wright S, Johnston M (eds) Measures in health psychology: a user’s portfolio. Causal control and self belief. NFER-NELSON, Windsor, pp 35–37

Janke W, Erdmann G, Gallus GW (2002) Stressverarbeitungsfragebogen SVF 78, 3. erweiterte Auflage. Hogrefe Publishers, Göttingen

Reinberg F, Vollmeyer R, Burns BD (2001) QCM: a questionnaire to assess current motivation in learning situations. University of Potsdam/Michigan State University, Potsdam/East Lansing

Sutton G (2009) Evaluating multidisciplinary health care teams: taking crisis out of CRM. Aust Health Rev 33(3):445–452

Pulich M, Tourigny L (2004) Workplace deviance: strategies for modifying employee behavior. Health Care Manag 23(4):290–301

Wetzel CM, Kneebone RL, Woloshynowych M, Nestel D, Moorthy K, Kidd J (2006) The effects of stress on surgical performance. Ann Surg 191:5–10

Wetzel CM, Black SA, Hanna GB, Athanasiou T, Kneebone RL, Nestel D, Wolfe JH, Woloshynowych M (2010) The effects of stress and coping on surgical performance during simulations. Ann Surg 251(1):171–176

Patey R, Flin R, Cuthbertson BH, MacDonald L, Mearns K, Cleland J, Williams D (2007) Patient safety: helping medical students understand error in healthcare. Qual Saf Health Care 16:256–259

Hassan I, Maschuw K, Rothmund M, Gerdes B (2006) Novices in surgery are the target group of a virtual reality training laboratory. Eur Surg Res 38(2):109–113

Hassan I, Gerdes B, Koller M, Langer P, Rothmund M, Zielke A (2006) Clinical background is required for optimum performance with a VR laparoscopy simulator. Comput Aided Surg 11(2):103–106

Cheadle WG (2006) Risk factors for surgical site infection. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 7(1):7–11

Sherman V, Feldman LS, Stanbridge D, Kazmi R, Fried GM (2005) Assessing the learning curve for the acquisition of laparoscopic skills on a virtual reality simulator. Surg Endosc 19(5):678–682

Grantcharov TP, Funch-Jensen P (2009) Can everyone achieve proficiency with the laparoscopic technique? Learning curve patterns in technical skills acquisition. Am J Surg 197(4):447–449

Schlosser K, Alkhawaga M, Gderdes B, Hassan I (2007) Training of laparoscopic skills with virtual reality simulator: a critical reappraisal of the learning curve. Eur Surg 39(3):180–184

Holge NJ, Briggs WM, Fowler DL (2007) Documenting a learning curve and test-retest reliability of two tasks on a virtual reality training simulator in laparoscopic surgery. J Surg Educ 64(6):424–430

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

K. Maschuw and K. Schlosser contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maschuw, K., Schlosser, K., Kupietz, E. et al. Do Soft Skills Predict Surgical Performance?. World J Surg 35, 480–486 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-010-0933-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-010-0933-2