Abstract

Background

Thyroid fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy is indeterminate or suspicious in up to 30% of cases and these patients are commonly subjected to at least a diagnostic hemithyroidectomy. If malignant on histology, a completion thyroidectomy is usually performed, which may be associated with higher morbidity. To determine the clinical utility of genetic testing in thyroid FNA biopsy, we conducted a prospective clinical trial.

Methods

Four hundred seventeen patients with 455 thyroid nodules were enrolled and had genetic testing for common somatic mutations (BRAF, NRAS, KRAS) and gene rearrangements (RET/PTC1, RET/PTC3, RAS, TRK1) by PCR and direct sequencing and by nested PCR, respectively. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of genetic testing in thyroid FNA biopsy were determined based on the histologic diagnosis.

Results

One hundred twenty-five of 455 thyroid nodule FNA biopsies were indeterminate or suspicious on cytologic examination. Overall, 50 mutations were identified (23 BRAF, 4 RET/PTC1, 2 RET/PTC3, 21 NRAS) in the thyroid FNA biopsies. There were significantly more mutations detected in malignant thyroid nodules than in benign (P = 0.0001). For thyroid FNA biopsies that were indeterminate or suspicious, genetic testing had a sensitivity of 12%, specificity of 98%, PPV of 38%, and NPV of 65%.

Conclusions

Genetic testing for somatic mutations in thyroid FNA biopsy samples is feasible and identifies a subset of malignant thyroid neoplasms that are indeterminate or suspicious on FNA biopsy. Genetic testing for common somatic genetic alterations thus could allow for more definitive initial thyroidectomy in those with positive results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The number of patients requiring clinical evaluation of thyroid nodules has dramatically increased over the past three decades due to the increasing number of thyroid incidentalomas [1]. Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy is the most accurate and cost-effective preoperative test to distinguish benign from malignant thyroid nodules. Most thyroid nodules are benign and only about 5% of them have malignant features on FNA biopsy and cytologic examination. Unfortunately, FNA biopsy is inconclusive in about 30% of all thyroid nodule biopsies because the cytologic features are indeterminate (follicular and Hürthle neoplasm), suspicious for malignancy but not completely diagnostic, or nondiagnostic (insufficient cells) upon cytologic examination. These patients are typically subjected to a diagnostic thyroidectomy to exclude a thyroid cancer diagnosis. Approximately 20% of patients with FNA biopsy showing indeterminate cytologic features will have thyroid cancer on histologic examination and may require a completion thyroidectomy.

Although FNA biopsy is accurate for benign and malignant interpretations, up to 10% of benign cytologic results may be false negatives and result in delay in diagnosis and treatment [2]. Also, significant discordance in the thyroid FNA biopsy cytologic interpretation has been reported on secondary review, especially for indeterminate, nondiagnostic, and suspicious findings [3]. The discordance in thyroid FNA biopsy interpretation can have significant management ramifications, ranging from patients avoiding thyroidectomy to allowing for more definitive initial surgical treatment in some cases. In order to decrease the need for unnecessary procedures and the additional costs incurred for diagnostic and completion thyroidectomies, new approaches to improving the diagnostic accuracy of FNA biopsy are needed.

Thyroid cancer marker research has been an active area with numerous approaches and candidate markers emerging but very few markers have been evaluated in a clinical trial to find whether they would be useful in clinical practice [4]. Molecular testing for common somatic mutations is one promising approach that has emerged because about two-thirds of thyroid cancers of follicular cell origin have one of the common genetic alterations (BRAF and RAS point mutations and RET/PTC and NTRK1 rearrangements), the genetic changes that occur are usually mutually exclusive events, and most of these genetic changes are specific to thyroid cancer of follicular cell origin (BRAF mutation and RET/PTC rearrangements). Somatic genetic alterations in thyroid cancer of follicular cell origin occur in genes involved in the tyrosine kinase signaling pathway (tyrosine kinase receptors: RET/PTC and NTRK1; intracellular signaling proteins: HRAS, KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF). The most prevalent genetic alteration is a point mutation in BRAF (V600E), which is present in approximately 40% of classic papillary thyroid cancers. RET/PTC and NTRK1 chromosomal rearrangements are present in about 30% and up to 15% of classic papillary thyroid cancers, respectively [4]. Hotspot mutations in NRAS and KRAS are more common in follicular thyroid carcinoma but also occur in benign thyroid neoplasm at a lower rate.

Several studies have reported that testing for the common somatic genetic changes in thyroid cancer may be useful for detecting thyroid cancer in indeterminate and suspicious thyroid FNA biopsy results [5–15]. Most of these studies were retrospective, tested for a limited number of genetic changes, and/or had a relatively small group of indeterminate, suspicious, and nondiagnostic FNA cytology groups. In fact, at the National Cancer Institute State of the Science Conference on thyroid FNA biopsy, it was suggested that although promising, there was limited data to recommend molecular testing for common somatic genetic alterations as an ancillary test to thyroid FNA biopsy for indeterminate and suspicious cytologic findings [16].

In this prospective clinical trial, we wanted to determine the feasibility and accuracy of molecular testing for a comprehensive panel of somatic genetic alterations associated with thyroid cancer of follicular cell origin in clinical thyroid FNA biopsy samples. We evaluated 455 thyroid nodule FNA biopsy samples from 417 patients using PCR and direct sequencing for hotspot mutations in BRAF, NRAS, and KRAS, and nested PCR for RET/PTC1, RET/PTC3, and NTRK1 rearrangements.

Materials and methods

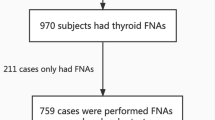

We recruited 438 subjects to participate in the study from June 2006 to July 2008 at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF); 417 agreed and 21 refused to participate (Fig. 1). The trial was approved by the Committee on Human Research at UCSF and registered at clinicaltrials.gov. Of the 455 thyroid FNA samples taken for analysis, 453 had an adequate nucleic acid yield for molecular testing. The FNA biopsy sample was dispensed into the TRIzol® (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) reagent and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction. The genetic testing results were not used to make clinical management decisions. Tissue diagnoses were confirmed by permanent histology, which was used as the gold standard to determine accuracy. All the diagnoses were based on the dominant nodule that was biopsied and not other areas of microscopic papillary thyroid cancer.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The amount of total RNA was determined by spectrophotometry using NanoDrop 3.0 (NanoDrop, Inc., Wilmington, DE). One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

PCR detection of somatic genetic alterations

Detection of hotspot mutations in BRAF, KRAS, and NRAS

The samples were tested for BRAF, KRAS, and NRAS hotspot mutations using PCR amplification with specific primers (Table 1) and the products were confirmed by gel electrophoresis. The PCR products were analyzed for the hotspot mutations by automated direct DNA sequencing. The PCR amplification reaction was performed using 75 ng of cDNA template in 2.5 μl 10× PCR buffer, 2.5 μl MgCl2 (25 mM), 0.25 μl dNTP (100 mM/4), 0.625 μl each primer (20 mM), 0.1 μl BSA (100×), 0.125 μl DNA polymerase (5 U/μl; AmpliTaq® Gold, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), and RNase-free H2O in a total volume of 25 μl.

PCR products were prepared for direct sequencing using enzymatic reactions of Exonuclease I (USB Corp., Cleveland, OH) and Shrimp Alkaline Phosphatase (USB Corp) to digest excess primers and dephosphorylate any free nucleotides. This was carried out using the iCycler at 37°C for 30 min followed by 15 min at 80°C. Samples were then prepared with reverse primers for each hotspot mutation and sequenced using the ABI BigDye v3.1 dye terminator sequencing chemistry with the ABI PRISM 3730xl capillary DNA analyzer. The sequences were analyzed to determine mutation status using Mutation Surveyor v3.10 (SoftGenetics, State College, PA).

Detection of RET/PTC1, RET/PTC3, and NTRK1 chromosomal rearrangements

The presence of RET/PTC1, RET/PTC3, and NTRK1 rearrangements in thyroid FNA biopsy samples was tested for using nested PCR (Table 2). The PCR product was subjected to gel electrophoresis to determine the presence of the specific rearrangement. For the RET/PTC1 and RET/PTC3 rearrangements, the PCR amplification reaction was performed using 75 ng of cDNA, 2.5 μl 10× PCR buffer, 2.5 μl MgCl2 (25 mM), 0.4 μl dNTP (100 mM/4), 0.625 μl each primer (20 mM), 0.1 μl BSA (100×), 0.125 μl DNA polymerase (5 U/μl; AmpliTaq Gold®, Applied Biosystems), and RNase-free H2O in a total volume of 25 μl. Positive controls for RET/PTC1 and RET/PTC3 were kindly provided by Dr. Yuri Nikiforov (University of Pittsburgh), and prior positive samples were used for NTRK1 rearrangement confirmed with nested PCR.

Statistical analyses

The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of genetic testing in thyroid FNA biopsy were determined based on the histologic diagnosis. Cases with no mutation and benign on histology were considered “true negative.” Cases with a mutation and malignant on histology were considered “true positive.” The overall accuracy was determined using all of the genetic alterations in combination and in a subset analysis excluding those mutations that may be present in benign thyroid neoplasm (NRAS and KRAS). The genetic testing was performed blinded to the FNA biopsy and histologic diagnosis.

Results

We detected 50 mutations in 400 thyroid FNA biopsy samples (23 BRAF V600E mutations, 21 NRAS mutations, and 4 RET/PTC1 and 2 RET/PTC3 rearrangements). The demographics of the study cohort and the interpretation of the FNA biopsy are summarized in Table 3. One hundred ten were indeterminate, 27 were suspicious, and 2 were nondiagnostic. Genetic alterations were significantly more common in malignant (28%) than in benign (6%) thyroid nodules (P < 0.0001). The malignancy rate was 32% in the indeterminate group, 56% in the suspicious-for-malignancy group, and 100% for the malignant group, based on permanent histologic examination (Fig. 2).

FNA cytology, histologic diagnosis, and mutation analysis results in thyroid FNA samples. One hundred four FNA samples had benign cytology and histology of dominant nodule. In these samples, there was one BRAF V600E mutation in a benign dominant thyroid nodule that had microscopic papillary thyroid cancer, one RET/PTC3 rearrangement in a benign thyroid nodule in the background of chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis, and nine NRAS mutations in adenomatoid nodules. FA follicular adenoma, HCA Hürthle cell adenoma, HN hyperplastic nodule, FVPTC follicular variant of papillary thyroid cancer, HCC Hürthle cell carcinoma, PTC papillary thyroid cancer, MTC medullary thyroid cancer, ATC anaplastic thyroid cancer

Molecular testing for all the common genetic alterations in combination had a sensitivity of 38%, specificity of 65%, PPV of 42%, and NPV of 65%. When cases positive for NRAS mutations were excluded because the mutations can be present in benign thyroid neoplasm, the sensitivity was 12% and specificity was 98% (2 false-positive results). One BRAF V600E mutation was detected in a benign dominant thyroid nodule that had microscopic papillary thyroid cancer. One RET/PTC3 rearrangement was detected in a benign thyroid nodule in the background of chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis.

In cases with indeterminate and suspicious thyroid FNA biopsy cytologic diagnosis, 17 cases (12%) were positive for BRAF V600E mutation and RET/PTC1 or RET/PTC3 rearrangements (Fig. 2). For initial treatment, 5 had a total thyroidectomy and 12 underwent only a diagnostic thyroidectomy. In these 12 cases, the presence of the somatic mutations specific for papillary thyroid cancer could have been used to allow a more definitive initial treatment as all of these patients went on to have a completion thyroidectomy based on the malignant histologic diagnosis.

Discussion

FNA biopsy has remained the most accurate and cost-effective preoperative diagnostic test to distinguish benign from malignant thyroid nodules. However, given that up to 30% of thyroid nodule FNA biopsy results are inconclusive, many patients still undergo a diagnostic thyroidectomy to exclude a cancer diagnosis, and they sometimes need a completion thyroidectomy. Moreover, the number of patients found to have a thyroid incidentaloma is increasing, and the number of patients with inconclusive FNA biopsy results is even larger. For these reasons, new ways to improve the diagnostic accuracy of thyroid FNA biopsy have been actively investigated. We used molecular testing for common somatic mutations in thyroid cancer of follicular cell origin to determine the accuracy and feasibility of prospectively testing clinical thyroid FNA biopsy samples. Based on the histologic diagnosis, we found a significantly higher rate of mutations in malignant than in benign thyroid neoplasms. However, molecular testing for a combination of mutations had low sensitivity and specificity. Exclusion of NRAS mutations increased specificity but lowered sensitivity. In 137 cases with indeterminate or suspicious thyroid FNA cytologic diagnosis, 17 cases were positive for BRAF V600E, RET/PTC1, or RET/PTC3 mutations, and in 12 cases a more definitive initial thyroidectomy procedure could have been performed based on the molecular testing result.

Mutation analysis for single or a combination of somatic mutations associated with thyroid cancer of follicular cell origin has been reported to improve the diagnostic accuracy ranging from 16 to 48% of cases with indeterminate and/or suspicious thyroid FNA cytologic diagnosis [5–11]. We found that in 12% of indeterminate and suspicious thyroid FNA results, mutation analysis could have allowed for a more definitive initial surgical treatment. The wide range in diagnostic accuracy improvement associated with molecular testing of thyroid FNA biopsies could be due to several reasons, including differences in FNA classification and diagnosis among centers, different rates of malignancy based on cytologic categories, thyroid nodule sampling, preservation of FNA biopsies, and the number of genetic alterations for which the biopsy was tested. We may also have observed a lower rate in sensitivity of combined mutation analysis because the remnant material from the thyroid FNA was used for molecular testing. Also, RNA was used to detect RET/PTC and NTRK1 rearrangements which may be expressed only at low levels, while they are more readily detectable if genomic DNA was used to detect rearrangements of these genes. Testing for PAX8/PPARγ rearrangement and HRAS mutation may also improve the sensitivity of molecular testing, but they are also present in benign follicular tumors at a relatively high rate and thus were not included in the panel of genetic alterations tested for in our study.

The strengths of our study are the large study cohort, prospective and blinded mutation analysis without clinical knowledge of the cytologic diagnosis, and the use of the remaining clinical FNA biopsy material. The follow-up time was not sufficient to determine accurately the false-negative rate of thyroid FNA biopsy and see if those benign cases with NRAS mutation would ever progress to a malignant tumor. Also, the use of RNA instead of DNA may have reduced the detection rate of gene rearrangements detected but the study was instituted for a dual purpose of evaluating a multigene expression assay [17].

In summary, molecular testing for a panel of common somatic genetic alterations in thyroid FNA biopsy with indeterminate or suspicious cytologic features is feasible and could allow for more definitive initial surgical therapy in a subset of cases. However, the NPV of genetic testing is too low to reduce the need for a diagnostic thyroidectomy in patients with indeterminate or suspicious thyroid FNA biopsies.

References

Mitchell JC, Parangi S (2004) Thyroid incidentalomas: a new epidemic. Curr Surg 61(6):545–551

Yeh MW, Demircan O, Ituarte P et al (2004) False-negative fine-needle aspiration cytology results delay treatment and adversely affect outcome in patients with thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid 14(3):207–215

Tan YY, Kebebew E, Reiff E et al (2007) Does routine consultation of thyroid fine-needle aspiration cytology change surgical management? J Am Coll Surg 205(1):8–12

Shibru D, Chung KW, Kebebew E (2008) Recent developments in the clinical application of thyroid cancer biomarkers. Curr Opin Oncol 20(1):13–18

Salvatore G, Giannini R, Faviana P et al (2004) Analysis of BRAF point mutation and RET/PTC rearrangement refines the fine-needle aspiration diagnosis of papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89(10):5175–5180

Cohen Y, Rosenbaum E, Clark DP et al (2004) Mutational analysis of BRAF in fine needle aspiration biopsies of the thyroid: a potential application for the preoperative assessment of thyroid nodules. Clin Cancer Res 10(8):2761–2765

Rowe LR, Bentz BG, Bentz JS (2006) Utility of BRAF V600E mutation detection in cytologically indeterminate thyroid nodules. Cytojournal 3:10

Jin L, Sebo TJ, Nakamura N et al (2006) BRAF mutation analysis in fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytology of the thyroid. Diagn Mol Pathol 15(3):136–143

Sapio MR, Posca D, Raggioli A et al (2007) Detection of RET/PTC, TRK and BRAF mutations in preoperative diagnosis of thyroid nodules with indeterminate cytological findings. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 66(5):678–683

Nikiforov YE, Steward DL, Robinson-Smith TM et al (2009) Molecular testing for mutations in improving the fine-needle aspiration diagnosis of thyroid nodules. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94(6):2092–2098

Yip L, Nikiforova MN, Carty SE et al (2009) Optimizing surgical treatment of papillary thyroid carcinoma associated with BRAF mutation. Surgery 146(6):1215–1223

Coyne C, Nikiforov YE (2010) RAS mutation-positive follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma arising in a struma ovarii. Endocr Pathol 21(2):144–147

Nikiforova MN, Nikiforov YE (2009) Molecular diagnostics and predictors in thyroid cancer. Thyroid 19(12):1351–1361

Nam SY, Han BK, Ko EY et al (2010) BRAF V600E mutation analysis of thyroid nodules needle aspirates in relation to their ultrasonographic classification: a potential guide for selection of samples for molecular analysis. Thyroid 20(3):273–279

Troncone G, Cozzolino I, Fedele M et al (2010) Preparation of thyroid FNA material for routine cytology and BRAF testing: a validation study. Diagn Cytopathol 38(3):172–176

Filie AC, Asa SL, Geisinger KR et al (2008) Utilization of ancillary studies in thyroid fine needle aspirates: a synopsis of the National Cancer Institute Thyroid Fine Needle Aspiration State of the Science Conference. Diagn Cytopathol 36(6):438–441

Kebebew E, Peng M, Reiff E et al (2006) Diagnostic and extent of disease multigene assay for malignant thyroid neoplasms. Cancer 106(12):2592–2597

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Moses, W., Weng, J., Sansano, I. et al. Molecular Testing for Somatic Mutations Improves the Accuracy of Thyroid Fine-needle Aspiration Biopsy. World J Surg 34, 2589–2594 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-010-0720-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-010-0720-0