Abstract

Background

A pooled post hoc responder analysis was performed to assess the clinical benefit of alvimopan, a peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor (PAM-OR) antagonist, for the management of postoperative ileus after bowel resection.

Methods

Adult patients who underwent laparotomy for bowel resection scheduled for opioid-based intravenous patient-controlled analgesia received oral alvimopan or placebo preoperatively and twice daily postoperatively until hospital discharge or for 7 postoperative days. The proportion of responders and numbers needed to treat (NNT) were examined on postoperative days (POD) 3–8 for GI-2 recovery (first bowel movement, toleration of solid food) and hospital discharge order (DCO) written.

Results

Alvimopan significantly increased the proportion of patients with GI-2 recovery and DCO written by each POD (P < 0.001 for all). More patients who received alvimopan achieved GI-2 recovery on or before POD 5 (alvimopan, 80%; placebo, 66%) and DCO written before POD 7 (alvimopan, 87%; placebo, 72%), with corresponding NNTs equal to 7.

Conclusions

On each POD analyzed, alvimopan significantly increased the proportion of patients who achieved GI-2 recovery and DCO written versus placebo and was associated with relatively low NNTs. The results of these analyses provide additional characterization and support for the overall clinical benefit of alvimopan in patients undergoing bowel resection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Postoperative ileus (POI) is an important clinical problem that occurs after major abdominal operations and is characterized by the inability to tolerate solid food, absence of passage of flatus and stool, pain and abdominal distension, nausea, vomiting, lack of bowel sounds, and accumulation of gas and fluids in the bowel [1]. Both endogenous opioids released in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract in response to stress and exogenous opioids used for pain management contribute to the complex etiology of POI [2, 3].

Postoperative ileus is associated with prolonged hospital length of stay (LOS), readmission, and increased risk for postoperative morbidity [4–8]. Gastrointestinal recovery is generally expected within 5 days (early recovery period) of bowel resection (BR) [9] and recovery delayed beyond 5 postoperative days (PODs) of BR (late recovery period) increases patient risk for morbidity and the probability of extending LOS [4, 5, 10–12]. Based on the placebo arms of alvimopan trials (mean discharge order [DCO] written = 6.1 days) [13] and Health Care Financing Administration database of major intestinal resections in 150 U.S. hospitals (mean LOS = 6.5 days) [14], a LOS of 7 days or more may be considered prolonged. Furthermore, national LOS statistics (including data representing more than 340,000 U.S. discharges in 1,054 U.S. hospitals) for large and small BR indicate that average LOS after these operations is substantially higher: 10 to 15 days [15]. Prolonged LOS may be associated with increased postoperative morbidity, such as nosocomial infections [16]. In addition to the clinical burden of POI, according to an analysis of a national database, hospitalization costs for patients with coded POI were substantially higher compared with patients without coded POI [10]. Furthermore, there is only one FDA-approved pharmacologic agent for the acceleration of GI recovery after BR.

Alvimopan (Entereg®, Adolor Corporation, Exton, PA), a recently approved peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor (PAM-OR) antagonist, was designed to mitigate the peripheral GI-related adverse effects of opioids without compromising centrally based analgesia [17]. Alvimopan was well tolerated, accelerated GI recovery, and reduced the time to hospital DCO written and POI-related morbidity after BR without compromising opioid-based analgesia in phase III efficacy trials [4, 18–22]. Although important, these components alone do not provide a complete assessment of the clinical benefit of a new therapy for the management of POI.

Therefore, a responder analysis, which takes individual responses to treatment into account, was performed to investigate further the clinically meaningful benefit of alvimopan for the management of POI after BR. This analysis investigated GI recovery and hospital DCO written over time during the early (PODs 3–5) and late (PODs 6–8) recovery periods in patients who received alvimopan or placebo in North American phase III efficacy trials [18–22].

Patients and methods

Adult patients (age ≥ 18 years) undergoing laparotomy for partial small or large BR with primary anastomosis and who were scheduled for postoperative pain management with intravenous opioid-based patient-controlled analgesia were eligible for enrollment [18–22]. Patients were excluded from eligibility if they were pregnant, currently using opioids or received an acute course of opioids (>3 doses) within 1 week of study entry, had a complete bowel obstruction, were undergoing total colectomy, colostomy, ileostomy, or coloanal or ileal pouch-anal anastomosis, or had a history of total colectomy, gastrectomy, gastric bypass, short bowel syndrome, or multiple previous abdominal operations performed by laparotomy. All patients signed a written, informed consent that was approved by individual institutional review boards [18–22].

Study design and treatments

This was a pooled post hoc analysis of four randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trials (14CL302, 14CL308, 14CL313, and 14CL314) [18–22]. The majority (>90%) of patients analyzed received placebo or alvimopan 12 mg at least 30 minutes but no longer than 5 hours before surgery and then twice daily after surgery until hospital discharge or for a maximum of 7 PODs (15 doses) while hospitalized. A multimodal, standardized accelerated postoperative care pathway was implemented in each study to facilitate GI recovery consistent with best-care practices: if the nasogastric tube (NGT) was kept in place after surgery, it was removed no later than noon on POD 1 before the first postoperative dose of study medication was administered; a liquid diet was offered and ambulation was encouraged on POD 1; solid food was offered on POD 2 [14].

Assessments

Gastrointestinal recovery was assessed by a composite measurement (GI-2), which included recovery of upper (toleration of solid food) and lower (first bowel movement) GI function, with time to achieve GI-2 based on the last event to occur. Postoperative LOS was defined as the calendar day of surgery to the calendar day of DCO written.

Responder analyses were performed at six cutoff time points on PODs 3 through 8. Postsurgery days (PSDs) were defined as 24-hour intervals after the end of surgery time (last suture or staple). Patients were considered responders if they achieved GI-2 recovery or DCO written by the cutoff time point and did not experience subsequent complications of POI. Complications of POI included prolonged LOS or readmission within 7 days after initial hospital discharge attributable to POI, paralytic ileus, or small intestinal obstruction reported as serious adverse events. Number needed-to-treat (NNT) analyses were performed to provide an estimate of the number of patients who would need to be treated to attain a favorable outcome. This type of analysis is directly applicable to clinical practice because it demonstrates the effort required to achieve a particular therapeutic target (e.g., achieving GI recovery within 5 days or discharge from the hospital less than 1 week from surgery) [22, 23] and is calculated from the absolute difference in the proportion of patients in alvimopan- and placebo-treated groups achieving an event.

Statistical methods

Fisher’s exact test was used to evaluate the treatment effect on the proportion of responders at each cutoff time point. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS® version 9.1 or higher (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patients

Of the 2,281 patients randomized in the 4 phase III trials, 1,409 patients underwent BR, received placebo or alvimopan, and were included in the modified intent-to-treat population (Table 1) [4]. Approximately half of all patients were women (51%), and the mean age was 61 years. The most common reason for surgery was colon or rectal cancer (51%).

Assessments

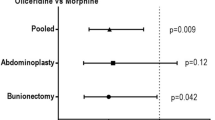

Overall, alvimopan significantly increased the proportion of patients who achieved GI-2 recovery on each day of the early and late recovery periods (P < 0.001 for all; Fig. 1a). Eighty percent of patients in the alvimopan group compared with 66% of patients in the placebo group achieved GI-2 recovery on or before POD 5. Moreover, alvimopan significantly increased the proportion of patients who achieved GI-2 recovery on each day of the early and late recovery periods irrespective of age or sex (P ≤ 0.03 for all). Significant increases (P < 0.001 for all) in the proportion of patients who achieved GI-2 recovery on each day were observed in white patients; however, significant increases (P < 0.05) were not observed in non-white patients on PSD 3 and 5. Only seven patients would need to be treated with alvimopan to reduce the risk associated with longer GI recovery (GI-2 recovery > 5 PSD) for one patient (Fig. 1b).

Alvimopan also significantly increased the proportion of patients who received DCO written on each day of the early and late recovery periods (P ≤ 0.001 for all; Fig. 2a). Consistent with GI-2 recovery results, more patients in the alvimopan group (87%) received DCO written before POD 7 compared with patients in the placebo group (72%). Alvimopan significantly increased the proportion of patients who received DCO written on each day of the early and late recovery periods regardless of age (P ≤ 0.025 for all). Significant increases (P < 0.001 for all) were observed regardless of sex on each day except for PSD 3 in women. Significant increases (P < 0.001 for all) in the proportion of patients who received DCO written on each day were observed in white patients. Significant increases (P < 0.05) were observed for non-white patients on each day except PSD 3. The proportion of patients who remained in the hospital on or after PSD 7 was reduced from 34% in the placebo group to 19% in the alvimopan group (P < 0.001; NNT = 7). Similarly, the proportion of elderly patients (≥65 years old) who received DCO written on or after PSD 7 was reduced from 35% in the placebo group to 17% in the alvimopan group (NNT = 5). Overall, NNT analysis indicated that seven patients would need to receive alvimopan to reduce the risk associated with prolonged LOS (DCO written ≥ 7 PSD) for one patient (Fig. 2b). Postoperative LOS was 1 day shorter in the alvimopan group (5.6 days) compared with the placebo group (6.6 days; P < 0.001).

The rates of readmission for any cause within 10 days (placebo group, 8%; alvimopan group, 5%; P = 0.01; NNT = 33) and readmission resulting from complications of POI within 7 days (placebo group, 2%; alvimopan group, 1%; P = 0.126; NNT = 100) were low in both groups. Of those patients who recovered GI-2 function in the early recovery period (placebo group, n = 461; alvimopan group, n = 572), 7% of patients in the placebo group and 4% of patients in the alvimopan group were readmitted to the hospital for any cause (P = 0.043), and no patient in either group was readmitted for POI, paralytic ileus, or small bowel obstruction. Furthermore, 12% of patients in the placebo group (n = 234) and 10% of patients in the alvimopan group (n = 142) who recovered GI-2 function in the late recovery period were readmitted for any cause (P = 0.614), and 6% of patients in the placebo group and 5% of patients in the alvimopan group were readmitted for POI, paralytic ileus, or small bowel obstruction (P = 0.818).

Discussion

Although there are no validated patient-reported outcome measures for POI, there is general agreement that providing a reduction in the time to GI recovery after BR is clinically meaningful to the patient. In addition to clinical benefit, it was previously reported that hospitalization costs for patients with an International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision (ICD-9), coded POI were substantially higher than for patients without coded POI ($18,877 vs. $9,460) and resulted in longer hospital LOS (11.5 vs. 5.5 days) [10]. The projected annual costs attributed to managing coded POI is $1.46 billion; however, this was estimated based on discharge coding of POI and likely underestimates the true prevalence rate [10]. Thus, in addition to the clinical burden associated with POI, a substantial economic burden is apparent.

Previously reported primary efficacy and morbidity analyses of alvimopan trials have demonstrated that alvimopan can significantly accelerate GI recovery in conjunction with a standardized accelerated postoperative care pathway without compromising opioid-based analgesia or increasing POI-related morbidity and was generally well tolerated [4, 13, 18–22]. Patients in the alvimopan-treated groups recovered both upper and lower GI function earlier compared with patients in the placebo-treated groups [13, 18–22].

The current responder analysis confirmed that alvimopan significantly increased the proportion of patients who achieved GI-2 recovery during both the early and late recovery periods in patients who underwent BR via laparotomy. Alvimopan also significantly increased the proportion of patients who received DCO written during both the early and late recovery periods. In general, GI-2 and DCO written were accelerated with alvimopan use regardless of age or sex; results for race were inconsistent, most likely because of the smaller sample size for non-white patients (n = 221) compared with white patients (n = 1,188). Patients treated with alvimopan were discharged from the hospital 1 day earlier than patients who received placebo, and rates of readmission were lower in the alvimopan group compared with the placebo group. Moreover, NNT analysis revealed that only a small number of patients (NNT = 7) would need to be treated to achieve risk reduction for one patient experiencing delayed GI recovery or prolonged LOS. In addition, the numbers needed to treat to reduce the risk of prolonged LOS in elderly patients was further reduced (NNT = 5). Hence, alvimopan use was associated with shifting more patients into the earlier phase of the recovery process. Moreover, NNT calculations indicated that 33 patients would need to be treated to prevent one readmission for any cause. A limitation of this NNT analysis is that by grouping patients together, it is assumed that patients who achieved or did not achieve GI-2 recovery on each day had an equal level of response, which is not the case. Thus, this analysis may underestimate the benefit of alvimopan.

By comparison, preventive therapies, such as the use of prophylactic antibiotic regimens to prevent postoperative wound infections in patients undergoing colorectal surgery or use of low molecular weight heparin or graduated compression stockings to prevent deep vein thrombosis, have NNTs ranging from 4 to 17 (calculated using absolute risk reduction) and have been incorporated into standard clinical practice based on benefits demonstrated in clinical trials [23–26] Indeed, wound infection after colorectal surgery was associated with an increase of approximately 12 hospital days and $1,500–$8,400 in costs, highlighting the value of instituting preventive therapies such as prophylactic antibiotic use into clinical practice [25]. By comparison, POI after colorectal surgery was associated with an increase of 4.9 hospital days and $8,296 in costs [27]. The NNTs for prevention therapies, such as prophylactic antibiotic use before colorectal surgery, provide support that a therapy (e.g., alvimopan) for an acute postoperative condition (e.g., POI) with similar NNTs (without increased risk) may represent meaningful patient benefit if incorporated into standard clinical practice, particularly because POI is recognized as the most common cause for increased LOS in these patients, and increased LOS after major surgery often is associated with increased risk for nosocomial complications [11, 28]. Additionally, the overall rate of POI is generally underreported and/or underrecognized, suggesting that the overall burden of POI on the health care system may be substantially underestimated [27].

Elderly patients (older than aged 60 years) are at a higher risk for postoperative morbidity and prolonged LOS after colorectal surgeries compared with younger patients [14, 29–32]. In this responder analysis, alvimopan significantly increased the proportion of patients who received DCO written during the early and late recovery periods and significantly reduced the proportion of patients with prolonged hospital stays (DCO written after 7 PODs) in both the overall and elderly trial populations compared with placebo. Therefore, these data indicate that alvimopan may be beneficial to patients who are at greater risk for prolonged LOS, such as the elderly. Such reductions in hospital LOS, prolonged LOS, and complications of POI (e.g., NGT insertion) may provide a benefit to patients and the healthcare system [5, 6].

In phase III trials, the accelerated GI recovery observed in patients who received alvimopan was not associated with additional complications of POI [4, 18–22]. Postoperative ileus-related morbidities, such as postoperative NGT insertion and prolonged LOS, were lower in patients who received alvimopan compared with placebo [4]. Furthermore, alvimopan was well tolerated in all phase III trials [18–22]. In a recent pooled analysis of patients who underwent BR in three phase III efficacy trials, the most common treatment-emergent adverse events were nausea and vomiting, and the incidences of these were lower in the alvimopan group compared with the placebo group (P < 0.05) [13].

Collectively, the data from this responder analysis in conjunction with previously reported efficacy, morbidity, and safety data provide a more complete assessment of the clinical benefit of alvimopan for the management of POI in patients who undergo BR. Alvimopan, therefore, may provide earlier GI recovery and discharge from the hospital without increased morbidity or interference with opioid pain management to a greater proportion of patients than what may be provided by a standardized accelerated postoperative care pathway alone.

References

Behm B, Stollman N (2003) Postoperative ileus: etiologies and interventions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 1:71–80

Kehlet H, Holte K (2001) Review of postoperative ileus. Am J Surg 182(Suppl):3S–10S

Lundgren O (2000) Sympathetic input into the enteric nervous system. Gut 47(Suppl 4):iv33–iv35; discussion iv36

Wolff BG, Weese JL, Ludwig KA et al (2007) Postoperative ileus-related morbidity profile in patients treated with alvimopan after bowel resection. J Am Coll Surg 204:609–616

Oderda GM, Said Q, Evans RS et al (2007) Opioid-related adverse drug events in surgical hospitalizations: impact on costs and length of stay. Ann Pharmacother 41:400–406

Kariv Y, Wang W, Senagore AJ et al (2006) Multivariable analysis of factors associated with hospital readmission after intestinal surgery. Am J Surg 191:364–371

Chang SS, Baumgartner RG, Wells N et al (2002) Causes of increased hospital stay after radical cystectomy in a clinical pathway setting. J Urol 167:208–211

Delaney CP, Senagore AJ, Viscusi ER et al (2006) Postoperative upper and lower gastrointestinal recovery and gastrointestinal morbidity in patients undergoing bowel resection: pooled analysis of placebo data from 3 randomized controlled trials. Am J Surg 191:315–319

Delaney CP (2004) Clinical perspective on postoperative ileus and the effect of opiates. Neurogastroenterol Motil 16(Suppl 2):61–66

Goldstein JL, Matuszewski KA, Delaney CP et al (2007) Inpatient economic burden of postoperative ileus associated with abdominal surgery in the United States. P&T 32:82–90

Person B, Wexner SD (2006) The management of postoperative ileus. Curr Probl Surg 43:6–65

Kehlet H, Buchler MW, Beart RW et al (2006) Care after colonic operation—is it evidence-based? Results from a multinational survey in Europe and the United States. J Am Coll Surg 202:45–54

Delaney CP, Wolff BG, Viscusi ER et al (2007) Alvimopan, for postoperative ileus following bowel resection. A pooled analysis of phase III studies. Ann Surg 245:355–363

Delaney CP, Fazio VW, Senagore AJ et al (2001) “Fast track” postoperative management protocol for patients with high co-morbidity undergoing complex abdominal and pelvic colorectal surgery. Br J Surg 88:1533–1538

H-CUPnet: national and regional estimates on hospital use for all patients from the HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample. http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/HCUPnet.jsp. Accessed 5 Jan 2010

Buchner AM, Sonnenberg A (2002) Epidemiology of Clostridium difficile infection in a large population of hospitalized U.S. military veterans. Dig Dis Sci 47:201–207

Adolor Corporation. Entereg® (alvimopan) Capsules. Prescribing Information. http://www.entereg.com/pdf/prescribing-information.pdf. Accessed 5 Jan 2010

Delaney CP, Weese JL, Hyman NH et al (2005) Phase III trial of alvimopan, a novel, peripherally acting, mu opioid antagonist, for postoperative ileus after major abdominal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 48:1114–1129

Viscusi ER, Goldstein S, Witkowski T et al (2006) Alvimopan, a peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonist, compared with placebo in postoperative ileus after major abdominal surgery: results of a randomized, double-blind, controlled study. Surg Endosc 20:64–70

Wolff BG, Michelassi F, Gerkin TM et al (2004) Alvimopan, a novel, peripherally acting mu opioid antagonist: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial of major abdominal surgery and postoperative ileus. Ann Surg 240:728–735

Ludwig KA, Enker WE, Delaney CP et al (2008) Gastrointestinal recovery in patients undergoing bowel resection: results of a randomized trial of alvimopan and placebo with a standardized accelerated postoperative care pathway. Arch Surg 143:1098–1105

Adolor Corporation. Entereg® (alvimopan) Capsules for postoperative ileus FDA Advisory Panel briefing document. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/DOCKETS/ac/08/briefing/2008-4336b1-02-Adolor.pdf. Accessed 5 Jan 2010

Baum ML, Anish DS, Chalmers TC et al (1981) A survey of clinical trials of antibiotic prophylaxis in colon surgery: evidence against further use of no-treatment controls. N Engl J Med 305:795–799

Anderson DR, O’Brien BJ, Levine MN et al (1993) Efficacy and cost of low-molecular-weight heparin compared with standard heparin for the prevention of deep vein thrombosis after total hip arthroplasty. Ann Intern Med 119:1105–1112

Song F, Glenny AM (1998) Antimicrobial prophylaxis in colorectal surgery: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Health Technol Assess 2:1–110

Wells PS, Lensing AW, Hirsh J (1994) Graduated compression stockings in the prevention of postoperative venous thromboembolism. A meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 154:67–72

Asgeirsson T, El-Badawi KI, Mahmood A et al (2010) Postoperative ileus: it costs more than you expect. J Am Coll Surg 210:228–231

Holte K, Kehlet H (2002) Postoperative ileus: progress towards effective management. Drugs 62:2603–2615

Schwandner O, Schiedeck TH, Bruch HP (1999) Advanced age—indication or contraindication for laparoscopic colorectal surgery? Dis Colon Rectum 42:356–362

Spivak H, Maele DV, Friedman I et al (1996) Colorectal surgery in octogenarians. J Am Coll Surg 183:46–50

Tartter PI (1988) Determinants of postoperative stay in patients with colorectal cancer. Implications for diagnostic-related groups. Dis Colon Rectum 31:694–698

Udelnow A, Leinung S, Schreiter D et al (2005) Impact of age on in-hospital mortality of surgical patients in a German university hospital. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 41:281–288

Acknowledgments

Support for studies described in this report and funding for medical editorial assistance was provided by Adolor Corporation, Exton, Pennsylvania, and GlaxoSmithKline, Philadelphia, PA. The authors thank Kerry O. Grimberg, PhD, and Bret A. Wing, PhD, ProEd Communications, Inc., for their medical editorial assistance with this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

Dr. Ludwig has nothing to disclose; Dr. Viscusi has received grant support from and is a consultant for Adolor Corporation; Dr. Wolff has been on the advisory board and has consulted for Adolor Corporation; Dr. Delaney is on the advisory board and is a consultant for Adolor Corporation; Dr. Senagore is on the advisory board and is a consultant for Adolor Corporation; Dr. Techner is an employee of Adolor Corporation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Clinical Trials Registration Numbers

NCT00388258, NCT00388479, NCT00388401, NCT00205842

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ludwig, K., Viscusi, E.R., Wolff, B.G. et al. Alvimopan for the Management of Postoperative Ileus After Bowel Resection: Characterization of Clinical Benefit by Pooled Responder Analysis. World J Surg 34, 2185–2190 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-010-0635-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-010-0635-9