Abstract

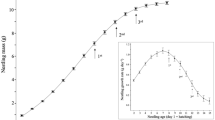

As offspring grow, parents often feed them with different sizes or taxa of prey to suit the changing nutritional or energetic demands. We investigated whether such changes in prey types were innate and inflexible or whether they were based on the proximate cue of offspring size. We created experimental broods in which parent blue tits Cyanistes caeruleus and pied flycatchers Ficedula hypoleuca received either older nestlings simulating rapid development or younger nestlings simulating delayed development. The size of prey increased over time in all brood types, suggesting a strong programmed pattern of foraging by parents. However, delayed broods were provisioned with smaller prey than control or advanced broods indicating some plasticity in the response by the parents to the size of nestlings. Although female birds brought smaller prey than male birds, both sexes showed the same rate of increase of prey size with time and brought similar types of prey items. The proportion of soft, digestible larva prey in the nestling diet decreased over time in pied flycatchers but increased in blue tits. Counter to the hypothesis that spiders provide unique and preferred nutrients for young nestlings, the proportion of arachnids in the diet did not change with nestling age for either species. The lack of treatment effect on the taxa of prey delivered suggests that temporal shifts in diet composition are not driven by the proximate cues of nestling age or size but that the feeding patterns are fairly innate and fixed in these altricial birds.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Arnold KE, Ramsay SL, Donaldson CH, Adam A (2007) Parental prey selection affects risk-taking behaviour and spatial learning in avian offspring. Proc R Soc Lond B 274:2563–2569

Bañbura J, Perret P, Blondel J, Sauvages A, Galan M-J, Lambrechts MM (2001) Sex differences in parental care in a Corsican blue tit Parus caeruleus population. Ardea 89:517–526

Bize P, Metcalfe NB, Roulin A (2006) Catch-up growth strategies differ between body structures: interactions between age and structure-specific growth in wild nestling alpine swifts. Funct Ecol 20:857–864

Breitwich R, Merritt PG, Whitesides GH (1986) Parental investment by the northern mockingbird: male and female roles in feeding nestlings. Auk 103:152–159

Browning LE, Young CM, Savage JL, Russell DJF, Barclay H, Griffith SC, Russell AF (2012) Carer provisioning rules in an obligate cooperative breeder: prey type, size and delivery rate. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 66:1639–1649

Courtney PA, Blokpoel H (1980) Food and indicators of food availability for common terns on the lower Great Lakes. Can J Zool 58:1318–1323

Cowie RJ, Hinsley SA (1988) Feeding ecology of great tits (Parus major) and blue tits (Parus caeruleus), breeding in suburban gardens. J Anim Ecol 57:611–626

Currie D, Nour N, Adriaensen F (1996) A new technique for filming prey delivered to nestlings, making minimal alterations to the nest box. Bird Study 43:380–382

Djerdali S, Tortosa FS, Doumandji S (2008) Do white stork (Ciconia ciconia) parents exert control over food distribution when feeding is indirect? Ethol Ecol Evol 20:361–374

Garcia-Navas V, Ferrer ES, Sanz JJ (2012) Prey selectivity and parental feeding rates of blue tits Cyanistes caeruleus in relation to nestling age. Bird Study 59:236–242

Garcia-Navas V, Ferrer ES, Sanz JJ (2013) Prey choice, provisioning behaviour, and effects of early nutrition on nestling phenotype of titmice. Ecoscience 20:9–18

Gosler AG (1987) Pattern and process in the bill morphology of the great tit Parus major. Ibis 129:451–476

Gottlander K (1987) Parental feeding behaviour and sibling competition in the pied flycatcher Ficedula hypoleuca. Ornis Scand 18:269–276

Krupa M (2004) Food of the willow warbler Phylloscopus trochilus nestlings: differences related to the age of nestlings and sex of feeding parents. Acta Ornithol 39:45–51

Low M, Makan T, Castro I (2012) Food availability and offspring demand influence sex-specific patterns and repeatability of parental provisioning. Behav Ecol 23:25–34

Magrath MJL, van Lieshout E, Visser GH, Komdeur J (2004) Nutritional bias as a new mode of adjusting sex allocation. Proc R Soc Lond B 271:S347–S349

Maziarz M, Wesolowski T (2010) Timing of breeding and nestling diet of wood warbler Phylloscopus sibilatrix in relation to changing food supply. Bird Study 57:540–552

Meunier M, Bedard J (1984) Nestling foods of the savannah sparrow. Can J Zool 62:23–27

Mitrus C, Mitrus J, Sikora M (2010) Changes in nestling diet composition of the red-breasted flycatcher Ficedula parva in relation to chick age and parental sex. Anim Biol 60:1–10

Moser ME (1986) Prey profitability for adult grey herons Ardea cinerea and the constraints on prey size when feeding young nestlings. Ibis 128:392–405

Orians GH, Pearson NE (1979) On the theory of central place foraging. In: Horn DJ, Mitchell RD, Stairs GR (eds) Analysis of ecological systems. Ohio State University Press, Columbus, pp 155–177

Orszaghova Z, Suplatova M, Orszagh I (2002) Changes in food composition of the tree sparrow (Passer montanus) nestlings. Biol Bratislava 57:251–259

Pagani-Núñez E, Ruiz I, Quesada J, Negro JJ, Senar JC (2011) The diet of great tit Parus major nestlings in a Mediterranean Iberian forest: the important role of spiders. Anim Biodivers Conserv 34:355–361

Radford AN (2008) Age-related changes in nestling diet of the cooperatively breeding green woodhoopoe. Ethology 114:907–915

Ramsay SL, Houston DC (2003) Amino acid composition of some woodland arthropods and its implications for breeding tits and other passerines. Ibis 145:227–232

Ricklefs RE (1967) A graphical method of fitting equations to growth curves. Ecology 48:978–983

Royama T (1966) Factors governing feeding rates, food requirement and brood size of nestling great tits Parus major. Ibis 108:313–347

Schwagmeyer PL, Mock DW, Parker GA (2002) Biparental care in house sparrows: negotiation or sealed bid? Behav Ecol 13:713–721

Slagsvold T (1998) On the origin and rarity of interspecific nest parasitism in birds. Am Nat 152:264–272

Slagsvold T, Hansen BT (2001) Sexual imprinting and the origin of obligate brood parasitism in birds. Am Nat 158:354–367

Slagsvold T, Wiebe KL (2007) Hatching asynchrony and early nestling mortality: the feeding constraint hypothesis. Anim Behav 73:691–700

Slagsvold T, Eriksen A, DeAyala RM, Husek H, Wiebe KL (2013) Post-fledging movements in birds: do tit families track environmental phenology? Auk 130:36–45

Sonerud GA, Steern R, Løw LM, Røed LT, Skar K, Selås V, Slagsvold T (2013) Linking delivery to capture: allocation of prey from male to offspring via female explains apparent inter-sexual difference in prey selection. Oecologia 172:93–107

SPSS. 2012. SPSS User's Guide Version 20.0. SPSS, inc., Chicago.

Wiebe KL, Slagsvold T (2009a) Parental sex differences in food allocation to junior brood members as mediated by prey size. Ethology 115:49–58

Wiebe KL, Slagsvold T (2009b) Mouth coloration in nestling birds: increasing detection or signalling quality? Anim Behav 78:1413–1420

Wiebe KL, Slagsvold T (2012) Brood parasites may use gape size constraints to exploit provisioning rules of smaller hosts: an experimental test of mechanisms of food allocation. Behav Ecol 23:391–396

Wright J (1998) Helpers-at-the-nest have the same provisioning rule as parents: experimental evidence from play-backs of chick begging. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 42:423–429

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided to KLW by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council.

Ethical Standards

The experiments comply with the current laws of the country in which they were performed and conducted with permission from the Directorate for Nature Management in Norway (2006/1890, 2007/3295) and from the Animal Welfare Committee of Norway (reference numbers 2006/14549, 2007/8921).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by M. Leonard

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wiebe, K.L., Slagsvold, T. Prey size increases with nestling age: are provisioning parents programmed or responding to cues from offspring?. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 68, 711–719 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-014-1684-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-014-1684-0