Abstract

Human male height is associated with mate choice and intra-sexual competition, and therefore potentially with reproductive success. A literature review (n = 18) on the relationship between male height and reproductive success revealed a variety of relationships ranging from negative to curvilinear to positive. Some of the variation in results may stem from methodological issues, such as low power, including men in the sample who have not yet ended their reproductive career, or not controlling for important potential confounders (e.g. education and income). We investigated the associations between height, education, income and the number of surviving children in a large longitudinal sample of men (n = 3,578; Wisconsin Longitudinal Study), who likely had ended their reproductive careers (e.g. > 64 years). There was a curvilinear association between height and number of children, with men of average height attaining the highest reproductive success. This curvilinear relationship remained after controlling for education and income, which were associated with both reproductive success and height. Average height men also married at a younger age than shorter and taller men, and the effect of height diminished after controlling for this association. Thus, average height men partly achieved higher reproductive success by marrying at a younger age. On the basis of our literature review and our data, we conclude that men of average height most likely have higher reproductive success than either short or tall men.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Body size is among the most conspicuous differences between males and females in many species. In most species of birds and mammals, males are larger than females, with perhaps the most striking example being the southern elephant seal, a species where the male is on average seven times larger than the female (Fairbairn et al. 2007). Such a size dimorphism is often explained in terms of sexual selection through either mate choice, with a preference for larger males by females, or through intra-sexual competition, with an increased advantage of larger males in male–male competition (Andersson 1994; Fairbairn et al. 2007).

Human males are ± 8% larger than females (Gray and Wolfe 1980), and male body size (i.e. height) plays a role in both human mate choice and intra-sexual competition. Women prefer taller rather than shorter men in online dating advertisements (Salska et al. 2008), questionnaire studies (Fink et al. 2007) and lab-based preference studies (reviewed by Courtiol et al. 2010), and these preferences seem to translate into real word decisions: taller men receive more responses to online dating advertisements (Pawlowski and Koziel 2002), are more likely to obtain a date (Sheppard and Stratham 1989), are more desirable in a speed-dating setting (Kurzban and Weeden 2005), have more attractive female partners (Feingold 1982) and are more likely to be married (Pawlowski et al. 2000). Although male height is related to mate choice in Western societies, recent studies indicate that preferences for taller men are not cross-culturally universal (Sear and Marlowe 2009).

There is also evidence to suggest that male height plays a role in intra-sexual competition. First of all, height is related to physical strength and thereby the chance of winning a physical contest (Sell et al. 2009; Carrier 2011). Second, taller men are less sensitive to cues of dominance in other men (Watkins et al. 2010), and respond with less jealousy towards socially and physically dominant rivals than shorter men (Buunk et al. 2008). Perceptions of height and dominance are also interlinked, as taller men are perceived as more dominant than shorter men and vice versa; dominant men are estimated as taller than less dominant men (Marsh et al. 2009). In addition, men who were perceived as taller were more influential in a negation task (Huang et al. 2002). Together, these findings may partly explain the observed association between height and social status, as taller men more often have a leadership position (Gawley et al. 2009), often emerge as leaders (Stogdill 1948), have higher starting salaries (Loh 1993) and have higher overall income (Judge and Cable 2004).

To be of evolutionary consequence, the advantage of increased height in mate choice and intra-sexual competition should translate into increased reproductive success for taller men. Several studies have examined this relationship without reaching consensus, and we provide a literature review including all studies that we could locate (n = 18; see “Online Resource 1” for the methods of the literature review and an extensive discussion of the findings) on the association between male height and reproductive success (Table 1). A variety of effects of male height on reproductive success were reported, including three positive, two negative, eight null and five curvilinear effects. There may be several reasons for this variation. First of all, selection pressures may differ among populations or over time. Siepielski et al. (2009) found considerable year to year variation in both strength and direction of selection for morphological traits, and this may also hold true for height. Variation in reported results can also stem from methodological reasons, such as differences in sampling procedure, in sample size and hence statistical power or in the variables considered in the statistical analysis. With respect to the sampling procedure, we find that several studies used samples that were clearly not representative of the population (e.g. only healthy men, men from low socio-economic class, or ‘troubled boys’), and it is unclear to which extent and how this would affect the results. Sampling procedure can possibly also explain the results of the study which has documented the strongest positive effect of height on reproductive success: Mueller and Mazur (2001) found clear evidence for directional selection for male height among men from the US military academy at West Point with military careers of 20 years or more. This sample is intentionally not representative of the whole population with respect to physical health and condition. More importantly, the physical selection is likely to be stronger on tall men, because for biomechanical reasons it is more difficult for tall men to meet physical requirements of the military such as the minimum number of eight correct pull-ups and 54 push-ups in 2 minutes (Mueller and Mazur 2001); hence, tall men that do meet those requirements may be exceptionally fit even compared to shorter men that meet the same requirements.

In addition, some of the variation in the effects found may be explained by the fact that very few studies were restricted to men who were at least close to having completed their reproductive careers (e.g. over 50 years in developed countries). If the association between male height and reproductive success is mostly determined at a later age, than effects of height are difficult to detect when using a sample of younger men. An additional methodological issue is the low statistical power for detecting an effect due to insufficient sample sizes, as selection gradients are typically low (Kingsolver et al. 2001), and therefore substantial samples are required to detect an effect.

As mentioned previously, male height is positively associated with social status (e.g. education (Silventoinen et al. 1999; Cavelaars et al. 2000) and income (Judge and Cable 2004)), which is an important determinant of male reproductive success (reviewed by Hopcroft 2006). In Western societies, education and income reflect social status but have large, opposing effects on reproductive success (reviewed by Hopcroft 2006; Nettle and Pollet 2008): in men, number of children increases with income but decreases with educational level. Therefore, in investigating male reproductive success, it is crucial to incorporate both education and income. Only very few studies that examined the relationship between height and reproductive success have controlled statistically for education and income (or proxies thereof).

In this study, we examine the relationship between height and reproductive success in a new sample in which some of the previously described limitations are overcome. First of all, we use a large sample of Wisconsin high-school graduates who were followed longitudinally and have likely ended their reproductive careers (i.e. over 60 years old). Second, we have high statistical power to find even weak effects of height, as the total sample included 3,578 men. Third, measures of education and income, both correlates of height, were available to disentangle possible confounding effects. Several (proxy) measures of reproductive success are available, including number of children ever born, number of surviving children, proportion of married offspring and potential proxies of mate value, such as number of marriages and age at first marriage.

Methods

We used the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS), a long-term study of a random sample of 10,317 men and women, born between 1937 and 1940, who graduated from Wisconsin high schools in 1957 (Wollmering 2006; http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/wlsresearch/). Survey data on a wide variety of topics were collected at several time points (in 1957, 1974, 1992/3 and 2003/4/5), covering almost 50 years of the participants’ lives. The WLS sample is broadly representative of white, non-Hispanic American men and women who have completed at least a high-school education. As about 75% of Wisconsin youth graduated from high school in the late 1950s (Wollmering 2006), our sample was biased towards well educated people. In line with the finding that height is positively related to education (Silventoinen et al. 1999), we find that the average height of our sample (179.20 cm) is taller than the average height of white US males from the same birth cohort (176.7 cm; Komlos and Lauderdale 2007). We will address this limitation further in our discussion.

Of particular interest for this study are the height, education, income, number of marriages, age at first marriage, number of children ever born, number of children surviving to reproductive age (18 years), age at birth first child and proportion of adult offspring (> 18 years) who are married (both sons and daughters). Because in the WLS, data were collected at several time points and by several methods (e.g. phone interviews, mail correspondence), and because of non-response, there is not complete information for all measures and sample sizes may differ for different measures.

Only biological children were included in the offspring counts. It was impossible to control for extra-pair paternity, as all data was self-reported by the respondent. For all measures except income and proportion of married offspring, we combined the data of separate time points to maximize sample size. For income we used the data collected in 1974 only (the respondent’s total earnings in 1974), because due to inflation, income is incomparable across decades (Pearson correlation with income in 1992; r = 0.48; p < 0.0001; n = 3,723; Pearson correlation with income in 2004; r = 0.39; p < 0.0001; n = 3,151). Education was measured as the number of years required to obtain the highest reported level of education (high school degree = 12 years of education; post-doctoral education = 21 years of education). For the proportion of married offspring, we only used data from 2004, as many children would not have reached adulthood when using data from earlier time points.

Statistical analyses were performed using R (version 2.13.1; R Development Core Team, 2011). All tests were two-tailed, and the significance level was set to α = 0.05. To examine the associations between height, education and income, we used Pearson correlations. For the effects of height on different measures of reproductive success, we used Poisson or logistic regression depending on the error distribution. Height squared was included to test for possible curvilinear effects. Whenever a curvilinear effect was found, we determined a confidence interval of the optimum of the effect, by simulating 1,000 responses (using the simulate{stats} function in R) and refitting the statistical model. In this way, 1,000 parameter estimates and hence optima are generated, and we could determine the 95% data range of these 1,000 samples.

Results

For 3,578 out of 4,991 men, height was available. The descriptive statistics for these men and the sample sizes available for all variables (and hence analyses) are summarized in Table 2. Poisson regression revealed that height had no significant linear effect on number of children ever born (Table 3). However, when we included the squared height in the analyses we found that height had a significant curvilinear effect on the number of children ever born (Table 3). Men with a height of 177.42 cm were predicted to have the most ever born children (Table 3).

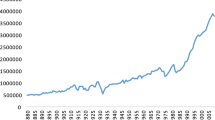

A better approximation of reproductive success is the number of children surviving to adulthood. Because child mortality was low in our sample (only 2.9%, i.e. in 92 out of 3,142 families at least one child died before reaching adulthood), the correlation between number of children ever born and number of children surviving to 18 years was high (Pearson r = 0.99; p < 0.0001; n = 3,578). Moreover, the proportion of children surviving was not related to height (Table 3). Not surprisingly therefore, we also found a curvilinear effect of height on children surviving to reproductive age (Table 3; Fig. 1a).

The effect of height on a the number of children surviving to 18 years (with Poisson regression lines), b the number of years of education and c annual income (US $) in 1974 binned by inch of height (mean ± s.e.). Given that height was measured in inches, we binned data using this unit of measurement (which was converted into centimeter). Bins below 65 in. and above 76 in. were collapsed

We also investigated the effect of male height on proxies of mating success: the number of marriages, the chance of being married and age at first marriage. Poisson and logistic regressions showed no linear or curvilinear effects of height on the number of marriages or the chance of being married (Table 3), but a linear regression on age at first marriage (log transformed to normalize its distribution) revealed that there was a curvilinear relationship between height and age at first marriage; average height men married youngest (Table 3). Similar effects of height were found with respect to the age at birth of the first child (Table 3). To examine whether the observed relationship between height and age at first marriage could account for the curvilinear effect of height on reproductive success, we re-analyzed this relationship while controlling for the age at first marriage. When excluding non-married men from the analyses, height was still significantly curvilinearly related to reproductive success in married men (Table 3). However, when controlling for age at first marriage, height was no longer a significant predictor of reproductive success in married men (Table 3), suggesting that age at first marriage can at least partly explain the observed patterns between height and reproductive success.

As height is related to education and income, which both have independent opposite effects on reproductive success, we repeated the analyses in which a significant effect of height was found while including education and income. As in previous studies, height was positively correlated with both education (Fig. 1b; Pearson r = 0.08, n = 3,577, p < 0.0001) and income (Fig. 1c; Pearson r = 0.09, n = 3,384, p < 0.0001). With respect to both the number of children ever born and surviving to reproductive age, education had a significant negative effect, while income had a significant positive effect, but the curvilinear effect of height remained significant when controlling statistically for these factors (Table 4). There were no significant two-way or three-way interactions between height, education and income on the number of children ever born or surviving to 18 years.

To compare the relative importance of height, education and income in explaining variation in number of children, we compared the change in deviance when removing the individual terms from the final model (Table 4). With respect to the number of children surviving to age 18, we found that the effect of income was about 2.8 times as strong as the effect of height (Income:ΔDeviance for income = 25.25 and ΔDeviance for height = 8.77, respectively). Similarly, the effect of education was 4.5 times stronger than the effect of height and about 1.5 times stronger than the effect of income (ΔDeviance for education = 40.06; see Table 4 for similar calculations on the other dependent variables).

We further compared the effects using the parameter estimates. When controlling for education and income, the maximal predicted reproductive success of 2.57 children was obtained by a man of 177.79 cm. Moving one standard deviation in height away from the optimum reduced the number of children by 2.1% (2.52), whereas moving two standard deviations away reduced the number of children by 8.1% (2.36). One standard deviation increase in years of education resulted in a decrease in number of children of 6.9%. For income, one standard deviation increase resulted in an increase of number of children of 5.4%. Therefore, while height is related to reproductive success, its effect is relatively small compared to education or income.

It is possible that a child’s reproductive success is dependent on the height of their father. To consider this possibility, we used the proportion of adult children being married. Paternal height was not significantly related to the proportion of married children, proportion of married sons or proportion of married daughters (Table 3).

For all significant curvilinear effects we determined the optimum, as well as a confidence interval around this optimum (Table 3). All optima were very close the average height of the entire sample (Table 3; range 175.90–179.47; range in Z-scores −0.51 to 0.04), and all 95% confidence intervals on the optima overlapped the sample average. Thus, optima were not significantly different from the average height in this population.

Discussion

In Wisconsin high-school graduates, average height men, compared to shorter and taller men, attained the highest reproductive success as measured by the number of children ever born and the number of children surviving to reproductive age. Thus, male height is curvilinearly related to reproductive success. In line with previous research, we found that education had a negative effect and that income had a positive effect on reproductive success (reviewed by Hopcroft 2006; Nettle and Pollet 2008). This underlines the importance of considering these two variables separately in a life history context, instead of using a combined social status measure (Hopcroft 2006). The effect of height was modest, being almost three times smaller than the effect of income, and 4.5 times smaller than the effect of education. Therefore, any selection pressure on male height in Western societies is likely relatively small in comparison to the selection on male education and male wealth.

The effect of male height on reproductive success could not be attributed to education or income in our sample. Thus, the shape of the curvilinear effect appears not to be a result of a differential effect of education or income across the height continuum. Apparently, being rich or being well educated does not provide the means to compensate for the effect of being short or tall on reproductive success, but neither does being poor or uneducated aggravate these effects. Income and education have pervasive effects on health and lifestyle, and the finding that the effect of height on reproductive success was insensitive to these factors suggests that there is a fundamental underlying biological process causing this effect. These findings are in broad agreement with the suggestion of Mueller et al. (1981) who reported that ‘the curvilinear association of fertility and bone [length] does not appear related to socioeconomic factors in this sample’ (p. 164), although they did not provide direct quantitative support for this suggestion.

A limitation of our study is that the sample was biased towards well-educated people (i.e. at least high-school education). As one out of four people never graduated from high-school in the 1950s, a part of the population is therefore not included in our sample. Given that height is positively related to education, our sample may have been biased towards taller men. Indeed, the average height in our sample (179.20 cm) was somewhat taller than the national average height of white men born in the same age cohort (176.7 cm; Komlos and Lauderdale 2007). Despite this limitation we still conclude that average height men had more reproductive success than their shorter and taller counterparts, as both the average height of the population as well as the national average height fell within the confidence interval for the estimated optima for number of children surviving to reproductive age (173.54–180.38 cm).

A limitation shared by all studies on the relationship between height and reproductive success, including ours, is that information on extra-marital offspring is lacking. Possibly taller and/or shorter men have more extra-pair offspring, which could offset the lower number of children within their own marriage, and we cannot test this hypothesis with the available data. In fact, we are not aware of any studies that have tested the relationships between height and either extra-pair mating success or the risk of losing fertilizations. However, non-paternity rates have been shown to be very low (around 3% as reviewed by Anderson 2006), making it unlikely that the quadratic association between height and reproductive success could be nullified by extra-pair offspring.

The number of children born to a male is only a proxy for fitness, which should ultimately be measured far into the future. Taller men may, for example, increase their relative reproductive success through increased survival chances of their offspring or the increased ability of their offspring to find a partner. We did not find any evidence for either of these processes, as height was not related to the proportion of children surviving to age 18 or the chance of adult offspring being married (either sons or daughters). For obvious reasons we cannot exclude the possibility that offspring reproductive success depends on paternal height when measured further into the future, but as paternal height was not related to offspring mating success, we anticipate that this possibility is not very likely.

Previous studies on the relationship between male height and reproductive success (Table 1) have reported a variety of effects of male height including positive (n = 3), negative (n = 2), no (n = 8) and curvilinear effects (n = 6) as in the present study (for an extensive discussion of the literature review and the variation in results, see “Online Resource 1”). We attribute most of this variation in results to differences in sampling procedure (e.g. biased samples or samples including very young men not likely to have ended their reproductive careers), low power of the majority of studies to detect the relevant effect size and the lack of testing for non-linear relations. The importance of testing for curvilinear effects is apparent from two re-analyses which found significant curvilinear effects, whereas the original studies reported no effect of height (Mitton 1975 re-analyzed Clark and Spuhler 1959; and we re-analyzed Damon and Thomas 1967). Furthermore, two studies conclude that their data show stabilising selection for height, without testing this statistically (Mueller et al. 1981; Goldstein and Kobyliansky 1984). Out of the ten studies considering non-linear effects, eight appear to support a curvilinear relationship. We therefore suggest that the most likely pattern with respect to the association between male height and reproductive success is average height men having most children. Further work remains necessary, however, as especially large samples from non-Western populations measuring reproductive success at the end of a male’s reproductive career are lacking.

Given our findings, it is puzzling that tall men are more attractive. Women might be more attracted to taller men because of the direct benefits it would confer to them, as height is universally positively associated with social status (Schumacher 1982; Silventoinen et al. 1999; Cavelaars et al. 2000; Judge and Cable 2004). Also in our study there was a positive association between height and income, but this did not translate into more reproductive success for taller men. In our sample, height was not associated with number of marriages or the chance of being married (in line with findings of a more traditional society: Hadza foragers of Tanzania, Sear and Marlowe 2009). However, average height men did marry at a younger age, suggesting that, to the extent that age of marriage is a proxy for mate value, average height men were more successful in finding a mate than either taller or shorter men. Furthermore, the relationship between height and age at marriage accounted (at least partly) for the effect of height on reproductive success. Thus, average height men attained more reproductive success by marrying at a younger age, potentially due to an increased length of the reproductive window.

The relationship between male height and reproductive success can also occur due to selection on correlated characters (e.g. indirect selection; Lande and Arnold 1983), rather than direct selection on male height. Inclusion of two known correlates of height and reproductive success (education and income) did not affect our estimates of selection on height, but nevertheless other (unknown) correlated factors might underlie or change this relationship. Whether selection on height acts directly or indirectly, the high heritability of height (around 0.8; Visscher et al. 2006) makes it likely that phenotypic selection on height directly affects the many genes coding for height.

References

Anderson KG (2006) How well does paternity confidence match actual paternity? Evidence from worldwide nonpaternity rates. Curr Anthropol 47:513–520

Andersson M (1994) Sexual selection. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Buunk AP, Park JH, Zurriaga R, Klavina L, Massar K (2008) Height predicts jealousy differently for men and women. Evol Hum Behav 29:133–139

Carrier DR (2011) The advantage of standing up to fight and the evolution of habitual bipedalism in hominins. PLoS One 6:e19630

Cavelaars AEJM, Kunst AE, Geurts JJM, Crialesi R, Grotvedt L, Helmert U, Lahelma E, Lundberg O, Mielck A, Rasmussen NK, Regidor E, Spuhler T, Mackenbach JP (2000) Persistent variations in average height between countries and between socio-economic groups: an overview of 10 European countries. Ann Hum Biol 27:407–421

Clark PJ, Spuhler JN (1959) Differential fertility in relation to body dimensions. Hum Nature-Int Bios 31:121–137

Courtiol A, Raymond M, Godelle B, Ferdy JB (2010) Mate choice and human stature: homogamy as a unified framework for understanding mating preferences. Evolution 64:2189–2203

Damon A, Thomas RB (1967) Fertility and physique—height weight and Ponderal Index. Hum Biol 39:5–13

Fairbairn DJ, Blanckenhorn WU, Székely T (2007) Sex, size and gender roles—evolutionary studies of sexual size dimorphism. Oxford University Press, New York

Feingold A (1982) Do taller men have prettier girlfriends? Psychol Rep 50:810–810

Fielding R, Schooling CM, Adab P, Cheng KK, Lao XQ, Jiang CQ, Lam TH (2008) Are longer legs associated with enhanced fertility in Chinese women? Evol Hum Behav 29:434–443

Fink B, Neave N, Brewer G, Pawlowski B (2007) Variable preferences for sexual dimorphism in stature (SDS): further evidence for an adjustment in relation to own height. Pers Indiv Differ 43:2249–2257

Gawley T, Perks T, Curtis J (2009) Height, gender, and authority status at work: analyses for a national sample of Canadian workers. Sex Roles 60:208–222

Genovese JEC (2008) Physique correlates with reproductive success in an archival sample of delinquent youth. Evol Psychol 6:369–385

Goldstein MS, Kobyliansky E (1984) Anthropometric traits, balanced selection and fertility. Hum Biol 56:35–46

Gray JP, Wolfe LD (1980) Height and sexual dimorphism of stature among human societies. Am J Phys Anthropol 53:441–456

Hopcroft RL (2006) Sex, status, and reproductive success in the contemporary United States. Evol Hum Behav 27:104–120

Huang W, Olson JS, Olson GM (2002) Camera angle affects dominance in video-mediated communication. Proc CHI 2002:716–717

Judge TA, Cable DM (2004) The effect of physical height on workplace success and income: preliminary test of a theoretical model. J Appl Psychol 89:428–441

Kingsolver JG, Hoekstra HE, Hoekstra JM, Berrigan D, Vignieri SN, Hill CE, Hoang A, Gibert P, Beerli P (2001) The strength of phenotypic selection in natural populations. Am Nat 157:245–261

Kirchengast S, Winkler EM (1995) Differential reproductive success and body dimensions in Kavango males from urban and rural areas in northern Namibia. Hum Biol 67:291–309

Kirchengast S (2000) Differential reproductive success and body size in !Kung San people from northern Namibia. Coll Antropol 24:121–132

Komlos J, Lauderdale BE (2007) The mysterious trend in American heights in the 20th century. Ann Hum Biol 34:206–215

Kurzban R, Weeden J (2005) HurryDate: mate preferences in action. Evol Hum Behav 26:227–244

Lande R, Arnold SJ (1983) The measurement of selection on correlated characters. Evolution 37:1210–1226

Lasker GW, Thomas R (1976) Relationship between reproductive fitness and anthropometric dimensions in a Mexican population. Hum Biol 48:775–791

Loh ES (1993) The economic effects of physical appearance. Soc Sci Quart 74:420–438

Marsh AA, Yu HH, Schechter JC, Blair RJR (2009) Larger than life: humans’ nonverbal status cues alter perceived size. PLoS One 4:e5707

Mitton JB (1975) Fertility differentials in modern societies resulting in normalizing selection for height. Hum Biol 47:189–200

Mueller WH (1979) Fertility and physique in a malnourished population. Hum Biol 51:153–166

Mueller WH, Lasker GW, Evans FG (1981) Anthropometric measurements and Darwinian fitness. J Biosoc Sci 13:309–316

Mueller U, Mazur A (2001) Evidence of unconstrained directional selection for male tallness. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 50:302–311

Nettle D (2002) Height and reproductive success in a cohort of British men. Hum Nature 13:473–491

Nettle D, Pollet TV (2008) Natural selection on male wealth in humans. Am Nat 172:658–666

Pawlowski B, Dunbar RIM, Lipowicz A (2000) Evolutionary fitness—tall men have more reproductive success. Nature 403:156–156

Pawlowski B, Koziel S (2002) The impact of traits offered in personal advertisements on response rates. Evol Hum Behav 23:139–149

R Development Core Team (2011) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org/

Salska I, Frederick DA, Pawlowski B, Reilly AH, Laird KT, Rudd NA (2008) Conditional mate preferences: factors influencing preferences for height. Pers Indiv Differ 44:203–215

Schumacher A (1982) On the significance of stature in human society. J Hum Evol 11:697–701

Scott EC, Bajema CJ (1981) Height, weight and fertility among the participants of the third Harvard growth study. Am J Phys Anthropol 54:276–276

Sear R (2006) Height and reproductive success—how a Gambian population compares with the west. Hum Nature-Int Bios 17:405–418

Sear R, Marlowe FW (2009) How universal are human mate choices? Size does not matter when Hadza foragers are choosing a mate. Biol Lett 5:606–609

Sell A, Cosmides L, Tooby J, Sznycer D, von Rueden C, Gurven M (2009) Human adaptations for the visual assessment of strength and fighting ability from the body and face. Proc R Soc Lond B 276:575–584

Shami SA, Tahir AM (1979) Operation of natural selection on human height. Pakistan J Zool 11:75–83

Sheppard JA, Stratham AJ (1989) Attractiveness and height: the role of stature in dating preference, frequency of dating and perceptions of attractiveness. Pers Soc Psych Bull 15:617–627

Siepielski AM, DiBattista JD, Carlson SM (2009) It’s about time: the temporal dynamics of phenotypic selection in the wild. Ecol Lett 12:1261–1276

Silventoinen K, Lahelma E, Rahkonen O (1999) Social background, adult body-height and health. Int J Epidemiol 28:911–918

Stogdill RM (1948) Personal factors associated with leadership: a survey of the literature. J Psychol 25:35–71

Visscher PM, Medland SE, Ferreira MAR, Morley KI, Zhu G et al (2006) Assumption-free estimation of heritability from genome-wide identity-by-descent sharing between full siblings. PLoS Genet 2:e41

Watkins CD, Fraccaro PJ, Smith FG, Vukovic J, Feinberg DR, DrBruine LM, Jones BC (2010) Taller men are less sensitive to cues of dominance in other men. Behav Ecol 21:943–947

Winkler EM, Kirchengast S (1994) Body dimensions and differential fertility in !Kung San males from Namibia. Am J Hum Biol 6:203–213

Wollmering E (2006) Wisconsin Longitudinal Study handbook. http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/wlsresearch/

Acknowledgements

This research used data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS) of the University of Wisconsin—Madison. Since 1991, the WLS has been supported principally by the National Institute on Aging (AG-9775 and AG-21079), with additional support from the Vilas Estate Trust, the National Science Foundation, the Spencer Foundation and the Graduate School of the University of Wisconsin—Madison. A public-use file of data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study is available from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study, University of Wisconsin—Madison, 1180 Observatory Drive, Madison, Wisconsin 53706 and at http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/wlsresearch/data/. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors. This research was supported by a grant to Abraham P. Buunk from the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, an NWO Veni grant to Thomas Pollet (451.10.032) and an NWO Vici grant to Simon Verhulst. We would like to thank Tim Fawcett for helpful advice. We thank two anonymous reviewers whose comments improved our manuscript.

Ethical standards

The study complies with the current laws of the country in which they were performed.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by T. Bakker

Electronic Supplementary Materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(PDF 50 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Stulp, G., Pollet, T.V., Verhulst, S. et al. A curvilinear effect of height on reproductive success in human males. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 66, 375–384 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-011-1283-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-011-1283-2