Abstract

Purpose

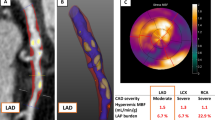

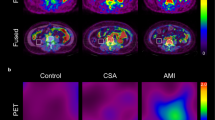

Measurements of [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake as a potential marker of the inflammatory activity of the vessel wall could be useful to identify vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques. The purpose of this study was to correlate the FDG uptake in the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) with cardiovascular risk factors, pericardial fat volume (PFV) and calcified plaque burden (CPB).

Methods

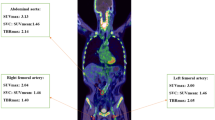

A total of 292 consecutive tumour patients were examined by whole-body FDG PET and contrast-enhanced CT. The blood pool-corrected standardized uptake value (target to background ratio, TBR) was measured in the LAD, and the contrast-enhanced CT images were used to measure the PFV and the CPB. The Spearman correlation coefficient and the unpaired t test were used for statistical comparison between image-based results and cardiovascular risk factors.

Results

Vascular FDG uptake could be measured for 161 of 292 (55%) patients without myocardial uptake, but the vessel uptake could not be distinguished in the other patients, due to pervasive myocardial uptake. The TBR of the LAD showed significant correlations with hypertension (R = 0.18; p < 0.05), coronary heart disease (R = 0.19; p < 0.05), body mass index (BMI) (R = 0.19; p < 0.05), CPB (R = 0.36; p < 0.001) and PFV (R = 0.20; p < 0.05), but not with other risk factors. Patients with a TBR in the upper tertile had a larger CPB and a higher PFV than patients with a TBR in the lower tertile (9.1 vs 3.5; p < 0.001 for CPB and 92.2 vs 71.5 mm3; p < 0.05 for PVF).

Conclusion

FDG uptake measurement in the LAD correlates with hypertension, coronary heart disease, BMI, PFV and CPB. However, due to myocardial FDG uptake these measurements are only feasible in one half of the patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Flegal K, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation 2009;119:e21–181. doi:CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191261 [pii] 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191261.

Naghavi M, Libby P, Falk E, Casscells SW, Litovsky S, Rumberger J, et al. From vulnerable plaque to vulnerable patient: a call for new definitions and risk assessment strategies: Part II. Circulation 2003;108:1772–8. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000087481.55887.C9 108/15/1772 [pii].

Naghavi M, Libby P, Falk E, Casscells SW, Litovsky S, Rumberger J, et al. From vulnerable plaque to vulnerable patient: a call for new definitions and risk assessment strategies: Part I. Circulation 2003;108:1664–72. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000087480.94275.97 108/14/1664 [pii].

Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1685–95. doi:352/16/1685 [pii] 10.1056/NEJMra043430.

Saam T, Hatsukami TS, Takaya N, Chu B, Underhill H, Kerwin WS, et al. The vulnerable, or high-risk, atherosclerotic plaque: noninvasive MR imaging for characterization and assessment. Radiology 2007;244:64–77. doi:244/1/64 [pii] 10.1148/radiol.2441051769.

Rudd JH, Myers KS, Bansilal S, Machac J, Rafique A, Farkouh M, et al. (18)Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging of atherosclerotic plaque inflammation is highly reproducible: implications for atherosclerosis therapy trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:892–6. doi:S0735-1097(07)01825-6 [pii] 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.05.024.

Rudd JH, Warburton EA, Fryer TD, Jones HA, Clark JC, Antoun N, et al. Imaging atherosclerotic plaque inflammation with [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Circulation 2002;105:2708–11.

Tawakol A, Migrino RQ, Bashian GG, Bedri S, Vermylen D, Cury RC, et al. In vivo 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging provides a noninvasive measure of carotid plaque inflammation in patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:1818–24. doi:S0735-1097(06)01980-2 [pii] 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.05.076.

Ben-Haim S, Kupzov E, Tamir A, Israel O. Evaluation of 18F-FDG uptake and arterial wall calcifications using 18F-FDG PET/CT. J Nucl Med 2004;45:1816–21. doi:45/11/1816 [pii].

Bural GG, Torigian DA, Chamroonrat W, Houseni M, Chen W, Basu S, et al. FDG-PET is an effective imaging modality to detect and quantify age-related atherosclerosis in large arteries. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2008;35:562–9. doi:10.1007/s00259-007-0528-9.

Rominger A, Saam T, Wolpers S, Cyran CC, Schmidt M, Foerster S, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT identifies patients at risk for future vascular events in an otherwise asymptomatic cohort with neoplastic disease. J Nucl Med 2009;50:1611–20. doi:jnumed.109.065151 [pii] 10.2967/jnumed.109.065151.

Virmani R, Burke AP, Farb A, Kolodgie FD. Pathology of the vulnerable plaque. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:C13–8. doi:S0735-1097(05)03137-2 [pii] 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.065.

Ambrose JA, Tannenbaum MA, Alexopoulos D, Hjemdahl-Monsen CE, Leavy J, Weiss M, et al. Angiographic progression of coronary artery disease and the development of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 1988;12:56–62. doi:0735-1097(88)90356-7 [pii].

Nissen SE. IVUS is redefining atherosclerotic disease. Am J Manag Care 2003;Suppl:2–3. doi:3356 [pii].

Leber AW, Becker A, Knez A, von Ziegler F, Sirol M, Nikolaou K, et al. Accuracy of 64-slice computed tomography to classify and quantify plaque volumes in the proximal coronary system: a comparative study using intravascular ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:672–7. doi:S0735-1097(05)03035-4 [pii] 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.058.

Budoff MJ, Shaw LJ, Liu ST, Weinstein SR, Mosler TP, Tseng PH, et al. Long-term prognosis associated with coronary calcification: observations from a registry of 25,253 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:1860–70. doi:S0735-1097(07)00680-8 [pii] 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.079.

Ding J, Hsu FC, Harris TB, Liu Y, Kritchevsky SB, Szklo M, et al. The association of pericardial fat with incident coronary heart disease: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Am J Clin Nutr 2009;90:499–504. doi:ajcn.2008.27358 [pii] 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27358.

Greif M, Becker A, von Ziegler F, Lebherz C, Lehrke M, Broedl UC, et al. Pericardial adipose tissue determined by dual source CT is a risk factor for coronary atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2009;29:781–6. doi:ATVBAHA.108.180653 [pii] 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.180653.

Rominger A, Saam T, Vogl E, Übleis C, la Fougère C, Foerster S, et al. In-vivo imaging of macrophage activity in the coronary arteries using 68 Ga-DOTA-TATE PET/CT: correlation with coronary calcium burden and risk factors. J Nucl Med 2010;51:193–7. doi:jnumed.109.070672 [pii] 10.2967/jnumed.10.070672

Nichols JH, Samy B, Nasir K, Fox CS, Schulze PC, Bamberg F, et al. Volumetric measurement of pericardial adipose tissue from contrast-enhanced coronary computed tomography angiography: a reproducibility study. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2008;2:288–95. doi:S1934-5925(08)00559-5 [pii] 10.1016/j.jcct.2008.08.008.

Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986;1:307–10.

Paulmier B, Duet M, Khayat R, Pierquet-Ghazzar N, Laissy JP, Maunoury C, et al. Arterial wall uptake of fluorodeoxyglucose on PET imaging in stable cancer disease patients indicates higher risk for cardiovascular events. J Nucl Cardiol 2008;15:209–17. doi:S1071-3581(08)00028-7 [pii] 10.1016/j.nuclcard.2007.10.009.

Yun M, Jang S, Cucchiara A, Newberg AB, Alavi A. 18F FDG uptake in the large arteries: a correlation study with the atherogenic risk factors. Semin Nucl Med 2002;32:70–6. doi:S0001299802500076 [pii].

Wykrzykowska J, Lehman S, Williams G, Parker JA, Palmer MR, Varkey S, et al. Imaging of inflamed and vulnerable plaque in coronary arteries with 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with suppression of myocardial uptake using a low-carbohydrate, high-fat preparation. J Nucl Med 2009;50:563–8. doi:jnumed.108.055616 [pii] 10.2967/jnumed.108.055616.

Inglese E, Leva L, Matheoud R, Sacchetti G, Secco C, Gandolfo P, et al. Spatial and temporal heterogeneity of regional myocardial uptake in patients without heart disease under fasting conditions on repeated whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT. J Nucl Med 2007;48:1662–9. doi:jnumed.107.041574 [pii] 10.2967/jnumed.107.041574.

Rudd JH, Myers KS, Bansilal S, Machac J, Pinto CA, Tong C, et al. Atherosclerosis inflammation imaging with 18F-FDG PET: carotid, iliac, and femoral uptake reproducibility, quantification methods, and recommendations. J Nucl Med 2008;49:871–8. doi:jnumed.107.050294 [pii] 10.2967/jnumed.107.050294.

Eisen A, Tenenbaum A, Koren-Morag N, Tanne D, Shemesh J, Imazio M, et al. Calcification of the thoracic aorta as detected by spiral computed tomography among stable angina pectoris patients: association with cardiovascular events and death. Circulation 2008;118:1328–34. doi:CIRCULATIONAHA.107.712141 [pii] 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.712141.

Rosito GA, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, Ruberg FL, Mahabadi AA, Vasan RS, et al. Pericardial fat, visceral abdominal fat, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and vascular calcification in a community-based sample: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2008;117:605–13. doi:CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743062 [pii] 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743062.

Menezes LJ, Kotze CW, Hutton BF, Endozo R, Dickson JC, Cullum I, et al. Vascular inflammation imaging with 18F-FDG PET/CT: when to image? J Nucl Med 2009;50:854–7. doi:jnumed.108.061432 [pii] 10.2967/jnumed.108.061432.

Acknowledgements

A substantial part of this work originated from the doctoral thesis of Sarah Wolpers.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Tobias Saam and Axel Rominger contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Saam, T., Rominger, A., Wolpers, S. et al. Association of inflammation of the left anterior descending coronary artery with cardiovascular risk factors, plaque burden and pericardial fat volume: a PET/CT study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 37, 1203–1212 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-010-1432-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-010-1432-2