Abstract

The anti-malarial drugs chloroquine (CQ) and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) have been suggested as promising agents against the new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 that induces COVID-19 and as a possible therapy for shortening the duration of the viral disease. The antiviral effects of CQ and HCQ have been demonstrated in vitro due to their ability to block viruses like coronavirus SARS in cell culture. CQ and HCQ have been proposed to reduce immune reactions to infectious agents, inhibit pneumonia exacerbation, and improve lung imaging investigations. CQ analogs have also revealed the anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects in treating viral infections and related ailments. There was, moreover, convincing evidence from early trials in China about the efficacy of CQ and HCQ in the anti-COVID-19 procedure. Since then, research and studies have been massive to ascertain these drugs’ efficacy and safety in treating the viral disease. In the present review, we construct a synopsis of the main properties and current data concerning the metabolism of CQ/HCQ, which were the basis of assessing their potential therapeutic roles against the new coronavirus infection. The effective role of QC and HCQ in the prophylaxis and therapy of COVID-19 infection is discussed in light of the latest international medical-scientific research results.

Key points

• Data concerning metabolism and properties of CQ/HCQ are discussed.

• The efficacy of CQ/HCQ against COVID-19 has been the subject of contradictory results.

• CQ/HCQ has little or no effect in reducing mortality in SARS-CoV-2-affected patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

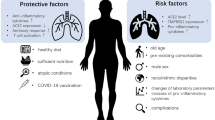

There is currently no general consensus on prophylactic or preventive therapy options for SARS-CoV-2, and a vaccine is expected to be produced and distributed to the population no earlier than 12–18 months from the pandemic outbreak. However, many clinical trials are underway to test the efficacy of old drugs reused against the novel coronavirus. Despite the time-consuming complexity of designing, researching, and producing new drugs, the repurposing of proven pharmaceutical remedies provides a proactive solution in responding rapidly and effectively to the SARS-CoV-2 disease (COVID-19) (Harrison 2020; Kearney 2020). Among such drugs, there are anti-malarial chloroquine (CQ) and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) that have been indicated as a possible therapy for shortening the duration of COVID-19 (Fig. 1) (Colson et al. 2020). Compared with QC, the derivative HQC has fewer side effects, drug-drug interactions, and toxicity. Clinical data for CQ and HCQ are well known, and there is nowadays ample expertise on their optimum usage, metabolism, the dose required, and routes of administration, transport, and excretion. First reports on CQ/HCQ have shown their potential role in reducing immune reactions to infection in inhibiting pneumonia exacerbation, reducing the fever duration, and improving lung health, in addition to its antiviral properties (Devaux et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020). Immediately after the outbreak began, Chinese and worldwide pharmaceutical industries intensified the production and import of chloroquine phosphate, and the pharmaceutical company Bayer accelerated the production and shipment of Resochin (chloroquine phosphate) to the provincial government of Guangdong. On 3 March 2020, the National Health Committee of the People’s Republic of China (NHC) released the “Diagnosis and Treatment of New Coronavirus Pneumonia” (Trial Edition 7) in which CQ was included in the antiviral therapy protocol. The established CQ doses were chloroquine phosphate (500 mg twice a day for 7 days for adults aged 18–65 with body weight over 50 kg; 500 mg twice a day for days 1 and 2 and 500 mg daily for days 3–7 for adults with body weight below 50 kg) (National Health Commission 2020).

Afterward, to test CQ’s efficacy and safety and its derivatives to treat SARS-CoV-2, a range of clinical trials started, and several are currently ongoing. On 5 November 2020, 90 trials have been registered (ClinicalTrials.gov 2020). Although some evidence with positive results early appeared, most of these studies are now considered of insufficient quality, limited, and mostly affected by high risks of bias (Gautret et al. 2020; Hernandez et al. 2020; Huang et al. 2020; Rosendaal 2020; Wang et al. 2020). Nowadays, there are increasing data reporting evidence of the ineffectiveness of CQ and HCQ in improving the prognosis or shorten the clinical course of COVID-19 (Gao et al. 2020a; Horby et al. 2020; Kashour et al. 2020; Lammers et al. 2020). Also, some reports highlight the severe risks, including death, when CQ is used in high dose and the potentially detrimental consequences of rapid dissemination of over-interpreted data of its efficacy (Das et al. 2020; Ektorp 2020; Kim et al. 2020; Touret and de Lamballerie 2020). In a recent report, Junqueira and Rowe highlighted the heterogeneous and insufficient approaches of early randomized control trials (RCTs) of the COVID-19 pandemic to measure CQ or HQ’s effectiveness and safety relevant to patients and clinical practice and the urgent need for well-designed high-quality RCTs (Junqueira and Rowe 2020). The present review analyzes QC and HCQ properties and activities, some of which were based on their assumed potential therapeutic role against the new coronavirus infection. It summarizes the results achieved so far about their real efficacy in the prophylaxis and therapy of COVID-19 infection.

Chloroquine metabolism

CQ is an amino acid tropic version of quinine, synthesized by Bayer in Germany in 1934, and originated as an adequate replacement for natural quinine approximately 70 years ago (Parhizgar and Tahghighi 2017; Winzeler 2008). Quinine is a compound present in the Peruvian-born bark of Cinchona trees and was the earlier drug of choice for malaria (Spiro 1986). CQ has been a front-line medicine for malaria prevention and prophylaxis for decades, and it is one of the most commonly used medicines in the world (White 1996). The properties and activities carried out by CQ and HCQ are discussed in the next sections.

Chloroquine as an antiviral agent

Since the late 1960s, the in vitro antiviral role of chloroquine has been established, and it has been shown that the development of many different viruses, like coronavirus SARS, can be blocked in cell culture by both CQ and HCQ (Keyaerts et al. 2004; Shimizu et al. 1972). CQ has also been used ex vivo for mice with ebolavirus, Nipah, and the infectious influenza virus (Dowall et al. 2015; Falzarano et al. 2015; Vigerust and McCullers 2007). Additionally, the antiviral activity of QC has also been shown in vivo, in mouse models, against other types of viruses, including human coronavirus OC43, enterovirus EV-A71, Zika virus, and influenza A H5N1 (Keyaerts et al. 2009; Li et al. 2017; Tan et al. 2018; Yan et al. 2013). Conversely, in a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial, CQ was not able to prevent influenza A (H1N1, H3N2) and B infection, and in another RCT, involving 307 dengue virus (DENV) infected patients, the drug has been shown to have only a little effect on reducing the duration of viremia (Paton et al. 2011; Tricou et al. 2010). The case of the chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is of particular interest. Essentially, CQ has demonstrated positive antiviral efficacy in vitro, conversely in vivo, with different animal models. CQ has been shown to improve alphavirus replication, most likely due to its immune modulation and anti-inflammatory properties (Coombs et al. 1981; Delogu and de Lamballerie 2011; Katz and Russell 2011; Roques et al. 2018).

Conversely, CQ therapy has been shown to worsen acute fever in a nonhuman primate model of CHIKV infection and prolongs the cellular immune response, leading to an inadequate viral clearance (Roques et al. 2018). A clinical trial, performed in Réunion Island during the 2006 chikungunya outbreak, concluded that oral CQ therapy did not change the progression of the acute disease and that chronic arthralgia was more common in diagnosed patients on day 300 post-illness than in the control group (Lamballerie et al. 2008; Roques et al. 2018). Overall, the review of recent studies shows that no acute virus infection in humans has been successfully treated with CQ to date. The drug has also been studied in chronic infections. Its use in the care of HIV-infected patients was found inconclusive, and the drug was not included in the group approved for HIV diagnosis (Chauhan and Tikoo 2015). The only significant effect of CQ in human virus infection treatment was found for chronic hepatitis C (HCV). CQ showed, in fact, an improvement in the early virological and biochemical responses in combination with pegylated interferon plus ribavirin (Helal et al. 2016). A temporary viral load reduction was observed in a small sample size pilot study in non-responder HCV patients (Peymani et al. 2016). However, this was not enough to provide CQ for patients with HCV in the unified treatment protocol procedures.

Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities

CQ and HCQ have shown anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities in treating viral infections and related pathologies in many ways (Al-Bari 2015; Giri et al. 2020). Numerous studies showed that simultaneous organ failure and hypovolemic shock found in fatal situations are most likely correlated not only with direct viral infections and the death of vulnerable cells (e.g., endothelial cells) but also with the activity of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and other mediators generated by damaged and activated cells such as monocytes and macrophages (Baize et al. 1999; Marzi et al. 2012). One of the cytokines strongly involved in filoviral pathologies is tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), which induces macrophages to release mediators, including reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide (NO). These cytokines allow endothelial cells to become more permeable and prone to be infected (Tracey and Cerami 1994). Therapeutic agents such as QC and analogs, which can prevent macrophage activation and inhibit TNF-α secretion by specific cells at the clinically appropriate concentration, are believed to offer some benefits in treating viral infections. CQ/HCQ has also been shown to decrease cytokine interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production (van den Borne et al. 1997). IFN-γ has been implicated in the pathologies of Ebola virus disease (EVD) and other infections (Al-Bari 2015; Villinger et al. 1999; Al-Bari 2017). IFN-γ has been reported to increase cell susceptibility to apoptosis by up-regulating the apoptosis antigen 1 (Fas) and Fas ligand expression in the severe instance of EVD (Schroder et al. 2004). IFN-γ also participates in severe apoptosis by activating through monocytes/macrophages, the neopterin production, and its corresponding derivative 7-8-dihydroneopterin, a biomarker of proinflammatory immune status (Murr et al. 2002). Therefore, CQ/HCQ, able to inhibit cytokines’ production and prevent macrophages’ activation, has attracted great attention as possible useful tools in treating patients affected by the new SARS-CoV-2.

Oxidative and nitrosative stress activity

The role of ROS in the pathogenesis of viral infections and the vulnerability of the immune system are factors that are usually underestimated (Paiva and Bozza 2014). Both viral infections and activation of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) generate ROS in a propagative manner, which results in oxidative damage. Increased ROS amounts have detrimental effects on cellular macromolecules such as lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids. Both endogenous (intracellular) and in particular exogenous (environmental) are sources of free radicals leading to DNA impairment and oxidative stress (Bjorklund et al. 2020; Zoroddu et al. 2014). Previous experiments in vivo and in vitro have shown that anti-malarial drugs CQ and primaquine can inhibit the hepatic microsomal mixed-function oxidases (Emerole and Thabrew 1983; Riviere and Back 1986; Thabrew and Ioannides 1984) and cause oxidative stress, mainly in erythrocytes, acting as a hemolytic agent in rats (Bolchoz et al. 2002). Chronic treatment with CQ has been found to have different effects on antioxidant enzymes in the liver than in rats’ kidneys. Prolonged intake of QC has been associated with a lowering of the liver’s antioxidant system and an increase in malondialdehyde production (MDA) in the kidneys. In both cases, the organs became more susceptible and subject to oxidative stress (Magwere et al. 1997). Historically, the effectiveness of QC for Plasmodium falciparum (NCBI:txid5833) has been attributed to the inhibition of heme polymerase leading to the accumulation of free heme, which is toxic to the malarial parasite (Slater and Cerami 1992). Free heme excess is connected to oxidative and inflammatory injury also in higher organisms. Several experimental data demonstrated that elevated free heme levels cause significant toxic effects on the liver, kidney, central nervous system, and heart tissue and that free heme catalyzes oxidation, protein aggregation, coagulation, covalent cross-linking, and degradation to small peptides.

Additionally, the heme-CQ complex results in a greater potential harmful species able to attack and disrupt intracellular targets such as DNA, lipid bilayer, cytoskeleton, and intermediate metabolic enzymes (Giovanella et al. 2015; Klouda and Stone 2020; Wagener et al. 2003). Heme alone can also cause lipid peroxidation, but this process is markedly amplified by the heme-CQ complex formation (Klouda and Stone 2020). It appears that CQ- and HCQ-induced systemic oxidative stress could contribute to the pathology of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and hypoxia status, which are often the cause of death in COVID-19 patients. Also, CQ induces increased NADPH-induced lipid peroxidation and glutathione content in rat retina (Bhattacharyya et al. 1983). Consequently, the retina may be particularly susceptible to oxidative stress damage during prolonged clinical CQ treatment (Michaelides et al. 2011). CQ and other 4-aminoquinolines have also been found to have an adverse effect on lysosomal activity. In human glioma cell lines, CQ induced loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), autophagic vacuoles accumulation, and cell viability loss. However, the CQ-induced glioma cell death has been mainly associated with MMP loss and not to oxidative stress (Vessoni et al. 2016). CQ stimulates inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression and NO synthesis in C6 glioma cells (Chen et al. 2005). This ability has been early demonstrated in vitro study in mouse, pig, and human endothelial cells (Ghigo et al. 1998). In conclusion, evidence indicates that prolonged QC/HQC treatment can induce oxidative stress and thus worsen the condition of COVID-19 patients.

Genotoxic and mutagenic activity

CQ has been reported at a certain concentration, increasing chromosome aberrations (Sahu and Kashyap 2012). For instance, Roy et al. measured the genotoxic ability of CQ in Swiss albino mice using chromosome aberration, micronucleus, and in vivo sperm abnormality test. They found that in the bone marrow cells, CQ causes chromosome aberration, as well as micronucleus. CQ’s genotoxicity was also tested by an abnormality test of the sperm head, for which a significant large rise in incidence was found following CQ treatment (Roy et al. 2008). In vivo tests revealed a very weak mutagenic effect of CQ, primaquine, and amodiaquine in mice’s bone marrow cells but confirmed their ability to induce chromosomal aberrations (Chatterjee et al. 1998). However, several other studies linked CQ with mutagenic processes in several bacterial strains (Giri et al. 2020). Shalumashvili and Sigidin researched the cytogenetic effects of CQ in the population of human lymphocytes. They reported that the application of CQ to a colony of human lymphocytes at stage G1 revealed that the compound inhibits cell mitotic function at 60 and 100 μg/ml concentrations (Shalumashvili and Sigidin Ia 1976). Farombi et al. studied CQ genotoxicity in rats using the alkaline comet assay. They reported greatly increase DNA strand breaks of rat liver cells in a CQ dose-dependent manner in a process in which ROS are probably the leading factors (Farombi 2006).

Despite its extensive human use, the genotoxic effects of anti-malarial drugs should be taken into account. In vitro studies on mammalian systems and reports on rheumatoid or aplastic anemia patients treated with CQ, together with multiple test systems investigations (i.e., Wistars rats, mouse bone marrow cells, and African common toad), showed the mutagenic, genotoxic, carcinogenic, and co-carcinogenic effect of CQ, in terms of chromosomal aberrations, sister-chromatid exchange, sex-linked recessive lethal, DNA damage, inhibition of DNA repair, micronuclei formation, and genesis of tumors (lymphosarcomas, myeloblastic leukemia) (Giri et al. 2020).

Long-term clinical studies and careful post-marketing monitoring are needed in the coming decades to see if any of the anti-malarial drugs can cause cancer in humans.

Inhibition of electron transport chain (TCA)

CQ and others and other anti-malarial drugs (primaquine, quinacrine, and naphthoquinone) inhibit the respiration process in the mitochondria of malaria protozoan parasites P. falciparum. It has been reported that the CQ/HCQ inhibition of the respiration process in the Plasmodium cells mitochondria can be removed through the introduction of Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10), suggesting that these drugs interfere with the respiration process probably also through interaction with CoQ10. This inhibition could be directly linked to their anti-malarial activity of CQ/HCQ. Nonetheless, the anti-malarial action is not strictly related to interaction with the biosynthesis or the work of CoQ10 but can include binding to enzymes closely associated with it (Skelton et al. 1968).

In the parasite cells, mitochondria morphologically and physiologically adapt to the hosts’ environmental conditions (Torrentino-Madamet et al. 2010). P. falciparum has minimal mitochondrial genomes, including three encoded proteins, and ribosomal RNAs extremely fragmented (Sahu and Kashyap 2012). P. falciparum mitochondria do not show complete glucose oxidation to support the synthesis of mitochondrial ATP. The energy metabolism of P. falciparum is different from that of the other mammalian hosts since it has a simple metabolism and many biosynthetic pathways are absent (Vaidya and Mather 2009). For example, the metabolic pathways of purine and pyrimidine are distinct from mammalian hosts. So targeting these pathways with newly designed drugs could overcome the problem of parasite resistance to currently available drugs (Cassera et al. 2011). Mitochondria, through several signaling mechanisms, play a critical role in the apoptotic cycle. A study performed on primary rat cortical neurons to check CQ’s effect (and bafilomycin A1) highlighted both drugs’ propensity to inhibit autophagy, disrupt mitochondrial activity, and cause mtDNA damage. CQ inhibits autophagy by interfering with lysosomal function preventing the fusion of lysosomes with autophagosomes. Furthermore, significant alterations of TCA cycle intermediates have been detected, in particular, linked to citrate synthase and glutaminolysis. Finally, CQ affects cellular bioenergy and metabolism, altering mitochondrial activity and damaging the TCA cycle (Redmann et al. 2017). In this context, there is some other evidence showing that high doses of CQ and HCQ affect human mitochondrial functions with significant alteration of the mitochondrial antioxidant buffering capacity and accentuating oxidative stress (Chaanine et al. 2015). Consequently, in pathological hypertrophy or heart failure patients, these drugs’ administration should be done with great caution since their high dose is metabolically cardiotoxic (Chaanine et al. 2015; Meyerowitz et al. 2020).

Zinc ionophores

Zinc modulates antiviral and antibacterial immunity and regulates the inflammatory response. Zinc ions are essential in various cellular processes and crucial to the proper folding and activity of various cellular enzymes and transcription factors (Chasapis et al. 2020; Zoroddu et al. 2019). Zn2+ is probably also an essential cofactor for several viral proteins. Nonetheless, metallothioneins retain the intracellular concentration of free Zn2+ at a relatively low level, possibly because zinc ions can act as an intracellular second messenger and induce apoptosis or decrease protein synthesis at high concentrations (Lazarczyk and Favre 2008). In eukaryotic cells, CQ exerts a pleiotropic influence involving an increase of vacuolar pH when embedded in acid organelles, such as lysosomes. This rise in pH interferes with lysosomal acidification that impairs autophagosome fusion and autophagic degradation (Mizushima et al. 2010). CQ has been shown to function synergistically with a protein kinase B (Akt) inhibitor to cause tumor cell death at the molecular level (Lamoureux et al. 2013). However, knowledge of the function of CQs in cancer cells at the cell and molecular levels is minimal. In previous studies, it is stated that zinc ions have an anticancer function by increasing the permeability of the lysosome membrane and by controlling gene expression (Yu et al. 2009; Zheng et al. 2012). Zinc compounds are considered a new group of potential anticancer agents, particularly zinc ionophores (Xue et al. 2014). These drugs are considered to have a possible role in anticancer therapy and anti-COVID-19 therapy as they have been shown to possess antiviral properties against previous SARS-CoV and the ability to regulate the inflammatory response. It has been shown that disulfiram, a molecule able to targeting Zn ions in the structure of essential coronavirus enzymes (papain-like proteases, PLpro) of MERS and SARS, results in their destabilization (Lin et al. 2018). A strategy targeting SCoV2-PLpro to suppress viral infection and promote antiviral immunity has been recently proposed as a therapeutic option against COVID-19 (Shin et al. 2020). It has been reported that Zn2+ is an in vitro inhibitor of coronavirus and arterivirus RNA polymerase activity and that zinc ionophores block the replication of these viruses in cell culture (te Velthuis et al. 2010).

Consequently, CQ and HCQ, as Zn2+ ionophores, can mediate the antiviral effect of Zn2+ against SARS-CoV-2. CQ and HCQ can be able to block virus replication by a direct mechanism resulting from the increase in pH in the intracellular vesicles, which inhibits the pH-dependent steps of the SARS-CoV-2 replication, and an indirect mechanism due to the targeting of extracellular Zn2+ to intracellular lysosomes, where zinc ions act as RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitors (Derwand and Scholz 2020). Consequently, zinc supplementation appears an ally in the fight against COVID-19, especially for people with proven Zn deficiency (Gasmi et al. 2020; Wessels et al. 2020). Several clinical trials investigating the role of zinc supplementation in enhancing the clinical efficacy of CQ and HCQ in the treatment of COVID-19 are currently running.

Iron antagonist

The research has long been on the topic of how CQ kills Plasmodium parasites. Dysregulation of intracellular heme levels is not tolerated and corresponds with the death of the parasite. Piling the molecules into an inactive nontoxic crystal called hemozoin, P. falciparum, prevents the harmful effects of heme. QC acts as hemozoin inhibitors (Fong and Wright 2013). When CQ binds to heme, it is impossible to make hemozoin, which causes the parasite to die in its waste (Sullivan 2017). This idea is further supported because CQ is distributed throughout the cytoplasm but accumulates within the parasite’s acidic digestive vacuole. Extracellularly, CQ/HCQ is often found in a protonated form that is incapable of entering the plasma membrane due to its positive charge.

However, according to the Henderson-Hasselbalch theorem, the unprotonated component that reaches the intracellular compartment becomes protonated in a way that is inversely proportional to the pH. The CQ/HCQ is abundant in acid organelles such as the endosome, Golgi vesicles, and lysosomes, where the pH is low, and the majority of CQ/HCQ molecules are charged positively, reaching millimolar concentrations compared with the nanomolar concentrations found in the plasma (Ohkuma and Poole 1981; Sullivan et al. 1996). CQ/HCQ is released primarily by exocytosis to the extracellular medium and/or through the activity of the multidrug resistance protein MRP-1, a cell surface drug transporter belonged to the ATP-binding cassette family, which further consists of the more extensively studied P-glycoprotein (Vezmar and Georges 1998; Vezmar and Georges 2000). It is well known that weak bases, as CQ/HCQ, impair many enzymes, including acid hydrolases, by increasing the pH of lysosomal and trans-network vesicles and prevent post-modification of newly synthesized proteins. The increase in endosomal pH caused by CQ modulates iron metabolism within human cells by impairing the endosomal release of iron from holo-transferrin, thus reducing the intracellular iron concentration. This decrease, in turn, affects the role of many cellular enzymes involved in pathways that lead to cellular DNA replication and the expression of numerous genes (Byrd and Horwitz 1991; Legssyer et al. 2003). Recently, (Quiros Roldan et al. 2020) hypothesized that clinical CQ/HCQ treatment could inhibit the complex between Tf and transferrin receptor 1 (TFR1), inducing a cellular iron deficiency which results in a negative influence of the SARS-CoV-2 life cycle, as has also been already shown for other human viruses (Drakesmith and Prentice 2008). However, currently, there is no experimental evidence to confirm this hypothesis. Conversely, a few in vitro studies have also shown that CQ can form a membrane-bound complex with heme that promotes lipid peroxidation due to close contact of iron ions with unsaturated fatty acids of membrane phospholipids (Klouda and Stone 2020). QC’s effect amplifies five times that seen with heme alone (Sugioka et al. 1987).

Chloroquine as treatment of SARS-CoV-2

CQ has been shown to possess a wide range of potential action against viruses, including most coronaviruses, particularly its close relative SARS-CoV-1. Consequently, in a public health emergency and the absence of any known effective therapy, it makes sense to examine the possible effects of CQ on SARS-CoV-2, which shares a similar phylogenetic heritage with previous coronavirus species and also because its entry occurs through the endolysosomal pathway (Burkard et al. 2014). CQ exerts several functions, one of which is to increase the pH of intracellular vesicles, interfering with the pH-dependent steps of viral replication, including maturation and fusion of endosomes and lysosomes and virus uncoating (Wang et al. 2020). It has also been suggested that CQ-induced altered ACE2 glycosylation that prevents S-protein binding, the eventual phagocytosis, and then releasing them into the cytoplasm where viral replication happens (Vincent et al. 2005; Yang et al. 2004). In vitro studies have indicated that both drugs could block the transport of the virus from early endosomes to endolysosomes, thus preventing the release of the viral genome and blocking its reproductive cycle (Liu et al. 2020). In addition to its direct antiviral effect, CQ inhibits cytokine synthesis, facilitating the inflammatory complications of viral infections (Karres et al. 1998; Savarino et al. 2003). Post-translational modification of membrane glycoproteins occurs within the vesicles of the endoplasmic and trans-Golgi network for enveloped viruses. This event requires protease, glycosyltransferase, and a low pH value for proper functioning. CQ, as a weak base, could inhibit this event. It is assumed that CQ, as a lysosomotropic agent, can effectively inhibit the coronavirus because the virus requires endosomal acidification for proper functioning. (Vincent et al. 2005). However, in a German study, it was observed that the virus might penetrate some types of respiratory epithelial cells with a pH-independent pathway. As a result, the authors stated that CQ is unable to appreciably interfere with viral entry or later stages of the viral replication cycle (Hoffmann et al. 2020). Based on the promising in vitro data of Wang et al. on the efficacy of both QC and antiviral remdesivir in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2, it has been proposed to test these drugs in patients with COVID-19 (Wang et al. 2020). Whether the in vitro activity of CQ and HCQ against the novel coronavirus resulted in appreciable activity in vivo with a safe and conventional human dosage. Following other early positive reports, CQ and HCQ were considered the best-known candidates for affecting the frequency of human SARS-CoV-2 infections (Gautret et al. 2020). In February 2020, the China National Center for Biotechnology Development suggested including CQ as a drug with a promising effectiveness profile against the new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. According to preliminary results, it has been reported that, compared to the control groups, approximately 100 affected patients treated with CQ experienced a greater gradual decrease in fever and progress in pulmonary computed tomography (CT) images with a shorter recovery period without apparent adverse effects (Cortegiani et al. 2020; Gao et al. 2020b). As a result, CQ was the first drug used on China’s front line and abroad for treating serious SARS-CoV-2 infections. From early trials in China, and soon in other countries, there was compelling evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of CQ and HCQ in the SARS-CoV-2 procedure. However, risk-of-bias assessments, unadjusted estimates of effect, and overall ratings of strength of evidence were found in several early RCTs and cohort studies (Chowdhury et al. 2020; Hernandez et al. 2020). Since then, scientific research has tried to find new evidence on the effectiveness of CQ and HCQ in COVID-19 therapy, with mixed results, debates, and sometimes reports with forced or unsupported data (Mehra et al. 2020). At the beginning of May, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the National Institute of Health (NIH) stated there is no significant evidence to point to the use of CQ/HCQ in the treatment of COVID-19 infection. However, in August 2020, a Belgian national observational study appeared, in which HCQ in a dose of 2400 mg over 5 days was associated positively with a significant decrease in mortality in hospitalized patients with respect to not treated patients (Catteau et al. 2020). Almost simultaneously in an Italian study, the drug HCQ, in a dose of 200 mg twice/day, was used in hospitalized COVID-19 patients showing a 30% reduction of overall mortality. Despite the limitation of the non-randomized study, the authors not discouraged the HCQ usage (Castelnuovo et al. 2020). However, in agreement with AIFA (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco), the Italian Ministry of Health, following IDSA guidelines, does not recommend using CQ/HQC in hospitalized and non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Instead, in August 2020, in the New Official Chinese Guidelines for the treatment of COVID-19 infection, chloroquine (instead of hydroxychloroquine) against covid-19 has been approved. However, later soon, based on evidence from multiple clinical trials, observational studies, and single-arm studies, NIH recommends against the use of CQ or HCQ with or without azithromycin for the treatment of COVID-19 in hospitalized patients, and in non-hospitalized patients (except in a clinical trial). In the COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel, NIH recommends against the use of high-dose chloroquine (600 mg twice daily for 10 days) for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection (National Institute of Health 2020). On 15 October 2020, one of the largest international RCT for COVID-19 treatments, “Solidarity Trial” launched by the World Health Organization and partners, published interim results. This RCT enrolled almost 12,000 patients from 500 hospitals over 30 countries and for all four treatments evaluated (remdesivir, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir/ritonavir, and interferon) reported that they have “little or no effect on overall mortality, initiation of ventilation, and duration of hospital stay in hospitalized patients” (World Health Organization 2020). The results, summed up and described here, illustrate a controversial hypothesis regarding the prospect that CQ or HCQ could be successful against the novel SARS-CoV-2. While it would seem true that CQ and HCQ do not have the effect of reducing mortality, a number of reports indicated that both drugs appear effective at the earliest stages of the infection (Carafoli 2020).

Conclusion

CQ is used to prevent and cure malaria and is beneficial in treating rheumatoid arthritis and lupus erythematosus as an anti-inflammatory agent. Studies have shown that it also has potential broad-spectrum antiviral activities by increasing the endosomal pH necessary for virus/cell fusion and interacting with SARS-CoV cell receptor glycosylation. Chloroquine’s antiviral and anti-inflammatory activities have consequently taken into account its potent effects in treating COVID-19 pneumonia patients.

Given the latest developments and the possible adverse impact of the drug found in previous attempts to treat acute viral diseases, the possibility of using CQ in the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 has been the subject of extensive scientific, political, and economic debate. Despite some positive early results, though subjected to substantial limitations, simplification, and probable over-interpretation of the data, the potential role of CQ and HCQ in fighting the virus has been emphasized, probably, beyond measure. Currently, no direct supporting data on the effective role of CQ and HCQ in the treatment for COVID-19 exist. Despite promising in vitro results, the latest largest international RCTs for COVID-19 treatments launched by WHO concluded that HCQ had little or no effect on overall mortality, initiation of ventilation, and duration of hospital stay in hospitalized patients, whereas potential effectiveness at the early stage of the diseases should be confirmed. However, we are still not sure if the CQ and HCQ saga is over.

References

Al-Bari MAA (2015) Chloroquine analogues in drug discovery: new directions of uses, mechanisms of actions and toxic manifestations from malaria to multifarious diseases. J Antimicrob Chemother 70(6):1608–1621. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkv018

Al-Bari MAA (2017) Targeting endosomal acidification by chloroquine analogs as a promising strategy for the treatment of emerging viral diseases. Pharmacol Res Perspect 5(1):e00293. https://doi.org/10.1002/prp2.293

Baize S, Leroy EM, Georges-Courbot M-C, Capron M, Lansoud-Soukate J, Debré P, Fisher-Hoch SP, McCormick JB, Georges AJ (1999) Defective humoral responses and extensive intravascular apoptosis are associated with fatal outcome in Ebola virus-infected patients. Nat Med 5(4):423–426. https://doi.org/10.1038/7422

Bhattacharyya B, Chatterjee TK, Ghosh JJ (1983) Effects of chloroquine on lysosomal enzymes, NADPH-induced lipid peroxidation, and antioxidant enzymes of rat retina. Biochem Pharmacol 32(19):2965–2968. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-2952(83)90403-3

Bjorklund G, Oliinyk P, Lysiuk R, Rahaman MS, Antonyak H, Lozynska I, Lenchyk L, Peana M (2020) Arsenic intoxication: general aspects and chelating agents. Arch Toxicol 94:1879–1897. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-020-02739-w

Bolchoz LJ, Morrow JD, Jollow DJ, McMillan DC (2002) Primaquine-induced hemolytic anemia: effect of 6-methoxy-8-hydroxylaminoquinoline on rat erythrocyte sulfhydryl status, membrane lipids, cytoskeletal proteins, and morphology. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 303(1):141–148. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.102.036921

Burkard C, Verheije MH, Wicht O, van Kasteren SI, van Kuppeveld FJ, Haagmans BL, Pelkmans L, Rottier PJ, Bosch BJ, de Haan CA (2014) Coronavirus cell entry occurs through the endo-/lysosomal pathway in a proteolysis-dependent manner. PLoS Pathog 10(11):e1004502. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004502

Byrd TF, Horwitz MA (1991) Chloroquine inhibits the intracellular multiplication of Legionella pneumophila by limiting the availability of iron. A potential new mechanism for the therapeutic effect of chloroquine against intracellular pathogens. J Clin Invest 88(1):351–357. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI115301

Carafoli E (2020) Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the prophylaxis and therapy of COVID-19 infection. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.09.128

Cassera MB, Zhang Y, Hazleton KZ, Schramm VL (2011) Purine and pyrimidine pathways as targets in Plasmodium falciparum. Curr Top Med Chem 11(16):2103–2115. https://doi.org/10.2174/156802611796575948

Castelnuovo AD, Costanzo S, Antinori A, Berselli N, Blandi L, Bruno R, Cauda R, Guaraldi G, Menicanti L, My I, Parruti G, Patti G, Perlini S, Santilli F, Signorelli C, Spinoni E, Stefanini GG, Vergori A, Ageno W, Agodi A, Aiello L, Agostoni P, Moghazi SA, Astuto M, Aucella F, Barbieri G, Bartoloni A, Bonaccio M, Bonfanti P, Cacciatore F, Caiano L, Cannata F, Carrozzi L, Cascio A, Ciccullo A, Cingolani A, Cipollone F, Colomba C, Crosta F, Pra CD, Danzi GB, D’Ardes D, Donati KDG, Giacomo PD, Gennaro FD, Di Tano G, D’Offizi G, Filippini T, Fusco FM, Gentile I, Gialluisi A, Gini G, Grandone E, Grisafi L, Guarnieri G, Lamonica S, Landi F, Leone A, Maccagni G, Maccarella S, Madaro A, Mapelli M, Maragna R, Marra L, Maresca G, Marotta C, Mastroianni F, Mazzitelli M, Mengozzi A, Menichetti F, Meschiari M, Minutolo F, Montineri A, Mussinelli R, Mussini C, Musso M, Odone A, Olivieri M, Pasi E, Petri F, Pinchera B, Pivato CA, Poletti V, Ravaglia C, Rinaldi M, Rognoni A, Rossato M, Rossi I, Rossi M, Sabena A, Salinaro F, Sangiovanni V, Sanrocco C, Scorzolini L, Sgariglia R, Simeone PG, Spinicci M, Trecarichi EM, Venezia A, Veronesi G, Vettor R, Vianello A, Vinceti M, Vocciante L, De Caterina R, Iacoviello L (2020) Use of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalised COVID-19 patients is associated with reduced mortality: findings from the observational multicentre Italian CORIST study. Eur J Intern Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2020.08.019

Catteau L, Dauby N, Montourcy M, Bottieau E, Hautekiet J, Goetghebeur E, van Ierssel S, Duysburgh E, Van Oyen H, Wyndham-Thomas C, Van Beckhoven D, Bafort K, Belkhir L, Bossuyt N, Caprasse P, Colombie V, De Munter P, Deblonde J, Delmarcelle D, Delvallee M, Demeester R, Dugernier T, Holemans X, Kerzmann B, Yves Machurot P, Minette P, Minon J-M, Mokrane S, Nachtergal C, Noirhomme S, Piérard D, Rossi C, Schirvel C, Sermijn E, Staelens F, Triest F, Goethem NV, Praet JV, Vanhoenacker A, Verstraete R, Willems E (2020) Low-dose hydroxychloroquine therapy and mortality in hospitalised patients with COVID-19: a nationwide observational study of 8075 participants. Int J Antimicrob Agents 56(4):106144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106144

Chaanine AH, Gordon RE, Nonnenmacher M, Kohlbrenner E, Benard L, Hajjar RJ (2015) High-dose chloroquine is metabolically cardiotoxic by inducing lysosomes and mitochondria dysfunction in a rat model of pressure overload hypertrophy. Phys Rep 3(7). https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.12413

Chasapis CT, Ntoupa PA, Spiliopoulou CA, Stefanidou ME (2020) Recent aspects of the effects of zinc on human health. Arch Toxicol 94:1443–1460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-020-02702-9

Chatterjee T, Muhkopadhyay A, Khan KA, Giri KA (1998) Comparative mutagenic and genotoxic effects of three antimalarial drugs, chloroquine, primaquine and amodiaquine. Mutagenesis 13(6):619–624. https://doi.org/10.1093/mutage/13.6.619

Chauhan A, Tikoo A (2015) The enigma of the clandestine association between chloroquine and HIV-1 infection. HIV Med 16(10):585–590. https://doi.org/10.1111/hiv.12295

Chen TH, Chang PC, Chang MC, Lin YF, Lee HM (2005) Chloroquine induces the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in C6 glioma cells. Pharmacol Res 51(4):329–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2004.10.004

Chowdhury MS, Rathod J, Gernsheimer J (2020) A rapid systematic review of clinical trials utilizing chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for COVID-19. Acad Emerg Med 27:493–504. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.14005

ClinicalTrials.gov (2020) ClinicalTrials.gov: a database of privately and publicly funded clinical studies conducted around the world. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home. Accessed 19 Oct 2020

Colson P, Rolain J-M, Lagier J-C, Brouqui P, Raoult D (2020) Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as available weapons to fight COVID-19. Int J Antimicrob Agents 55(4):105932–105932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105932

Coombs K, Mann E, Edwards J, Brown DT (1981) Effects of chloroquine and cytochalasin B on the infection of cells by Sindbis virus and vesicular stomatitis virus. J Virol 37(3):1060–1065

Cortegiani A, Ingoglia G, Ippolito M, Giarratano A, Einav S (2020) A systematic review on the efficacy and safety of chloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19. J Crit Care 57:279–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.03.005

Das RR, Jaiswal N, Dev N, Naik SS, Sankar J (2020) Efficacy and safety of anti-malarial drugs (chloroquine and hydroxy-chloroquine) in treatment of COVID-19 infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne) 7:482. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2020.00482

Delogu I, de Lamballerie X (2011) Chikungunya disease and chloroquine treatment. J Med Virol 83(6):1058–1059. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.22019

Derwand R, Scholz M (2020) Does zinc supplementation enhance the clinical efficacy of chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine to win today’s battle against COVID-19? Med Hypotheses 142:109815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109815

Devaux CA, Rolain J-M, Colson P, Raoult D (2020) New insights on the antiviral effects of chloroquine against coronavirus: what to expect for COVID-19? Int J Antimicrob Agents 55(5):105938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105938

Dowall SD, Bosworth A, Watson R, Bewley K, Taylor I, Rayner E, Hunter L, Pearson G, Easterbrook L, Pitman J (2015) Chloroquine inhibited Ebola virus replication in vitro but failed to protect against infection and disease in the in vivo guinea pig model. J Gen Virol 96(Pt 12):3484–3492. https://doi.org/10.1099/jgv.0.000309

Drakesmith H, Prentice A (2008) Viral infection and iron metabolism. Nat Rev Microbiol 6(7):541–552. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro1930

Ektorp E (2020) Death threats after a trial on chloroquine for COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis 20(6):661. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30383-2

Emerole GO, Thabrew MI (1983) Changes in some rat hepatic microsomal components induced by prolonged administration of chloroquine. Biochem Pharmacol 32(20):3005–3009. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-2952(83)90241-1

Falzarano D, Safronetz D, Prescott J, Marzi A, Feldmann F, Feldmann H (2015) Lack of protection against ebola virus from chloroquine in mice and hamsters. Emerg Infect Dis 21(6):1065–1067. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2106.150176

Farombi E (2006) Genotoxicity of chloroquine in rat liver cells: protective role of free radical scavengers. Cell Biol Toxicol 22(3):159–167

Fong KY, Wright DW (2013) Hemozoin and antimalarial drug discovery. Future Med Chem 5(12):1437–1450. https://doi.org/10.4155/fmc.13.113

Gao G, Wang A, Wang S, Qian F, Chen M, Yu F, Zhang J, Wang X, Ma X, Zhao T, Zhang F, Chen Z (2020a) Brief report: retrospective evaluation on the efficacy of lopinavir/ritonavir and chloroquine to treat nonsevere COVID-19 patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 85(2):239–243. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000002452

Gao J, Tian Z, Yang X (2020b) Breakthrough: chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 associated pneumonia in clinical studies. Biosci Trends 14:72–73. https://doi.org/10.5582/bst.2020.01047

Gasmi A, Tippairote T, Mujawdiya PK, Peana M, Menzel A, Dadar M, Gasmi Benahmed A, Bjorklund G (2020) Micronutrients as immunomodulatory tools for COVID-19 management. Clin Immunol 220:108545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2020.108545

Gautret P, Lagier J-C, Parola P, Hoang VT, Meddeb L, Mailhe M, Doudier B, Courjon J, Giordanengo V, Vieira VE, Tissot Dupont H, Honoré S, Colson P, Chabrière E, La Scola B, Rolain J-M, Brouqui P, Raoult D (2020) Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents 56(1):105949–105949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949

Ghigo D, Aldieri E, Todde R, Costamagna C, Garbarino G, Pescarmona G, Bosia A (1998) Chloroquine stimulates nitric oxide synthesis in murine, porcine, and human endothelial cells. J Clin Invest 102(3):595–605. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI1052

Giovanella F, Ferreira GK, de Pra SD, Carvalho-Silva M, Gomes LM, Scaini G, Goncalves RC, Michels M, Galant LS, Longaretti LM, Dajori AL, Andrade VM, Dal-Pizzol F, Streck EL, de Souza RP (2015) Effects of primaquine and chloroquine on oxidative stress parameters in rats. An Acad Bras Cienc 87(2 Suppl):1487–1496. https://doi.org/10.1590/0001-3765201520140637

Giri A, Das A, Sarkar AK, Giri AK (2020) Mutagenic, genotoxic and immunomodulatory effects of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine: a review to evaluate its potential to use as a prophylactic drug against COVID-19. Genes Environ 42:25–25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41021-020-00164-0

Harrison C (2020) Coronavirus puts drug repurposing on the fast track. Nat Biotechnol 38(4):379–381. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41587-020-00003-1

Helal GK, Gad MA, Abd-Ellah MF, Eid MS (2016) Hydroxychloroquine augments early virological response to pegylated interferon plus ribavirin in genotype-4 chronic hepatitis C patients. J Med Virol 88(12):2170–2178. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.24575

Hernandez AV, Roman YM, Pasupuleti V, Barboza JJ, White CM (2020) Update alert 2: hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine for the treatment or prophylaxis of COVID-19. Ann Intern Med 173(7):W128–W129. https://doi.org/10.7326/L20-1054

Hoffmann M, Mösbauer K, Hofmann-Winkler H, Kaul A, Kleine-Weber H, Krüger N, Gassen NC, Müller MA, Drosten C, Pöhlmann S (2020) Chloroquine does not inhibit infection of human lung cells with SARS-CoV-2. Nature 585(7826):588–590. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2575-3

Horby P, Mafham M, Linsell L, Bell JL, Staplin N, Emberson JR, Wiselka M, Ustianowski A, Elmahi E, Prudon B, Whitehouse T, Felton T, Williams J, Faccenda J, Underwood J, Baillie JK, Chappell LC, Faust SN, Jaki T, Jeffery K, Lim WS, Montgomery A, Rowan K, Tarning J, Watson JA, White NJ, Juszczak E, Haynes R, Landray MJ (2020) Effect of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 383:2030–2040. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2022926

Huang M, Li M, Xiao F, Pang P, Liang J, Tang T, Liu S, Chen B, Shu J, You Y, Li Y, Tang M, Zhou J, Jiang G, Xiang J, Hong W, He S, Wang Z, Feng J, Lin C, Ye Y, Wu Z, Li Y, Zhong B, Sun R, Hong Z, Liu J, Chen H, Wang X, Li Z, Pei D, Tian L, Xia J, Jiang S, Zhong N, Shan H (2020) Preliminary evidence from a multicenter prospective observational study of the safety and efficacy of chloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19. Natl Sci Rev 7(9):1428–1436. https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwaa113

Junqueira DR, Rowe BH (2020) Efficacy and safety outcomes of proposed randomized controlled trials investigating hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Clin Pharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.14598

Karres I, Kremer J-P, Dietl I, Steckholzer U, Jochum M, Ertel W (1998) Chloroquine inhibits proinflammatory cytokine release into human whole blood. Am J Phys Regul Integr Comp Phys 274(4):R1058–R1064. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.4.R1058

Kashour Z, Riaz M, Garbati MA, AlDosary O, Tlayjeh H, Gerberi D, Murad MH, Sohail MR, Kashour T, Tleyjeh IM (2020) Efficacy of chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother 76:30–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkaa403

Katz SJ, Russell AS (2011) Re-evaluation of antimalarials in treating rheumatic diseases: re-appreciation and insights into new mechanisms of action. Curr Opin Rheumatol 23(3):278–281. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOR.0b013e32834456bf

Kearney J (2020) Chloroquine as a potential treatment and prevention measure for the 2019 novel coronavirus: a review. Preprints:2020030275. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202003.0275.v1

Keyaerts E, Vijgen L, Maes P, Neyts J, Van Ranst M (2004) In vitro inhibition of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus by chloroquine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 323(1):264–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.085

Keyaerts E, Li S, Vijgen L, Rysman E, Verbeeck J, Van Ranst M, Maes P (2009) Antiviral activity of chloroquine against human coronavirus OC43 infection in newborn mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53(8):3416–3421. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01509-08

Kim AHJ, Sparks JA, Liew JW, Putman MS, Berenbaum F, Duarte-García A, Graef ER, Korsten P, Sattui SE, Sirotich E, Ugarte-Gil MF, Webb K, Grainger R (2020) A rush to judgment? Rapid reporting and dissemination of results and its consequences regarding the use of hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19. Ann Intern Med 172(12):819–821. https://doi.org/10.7326/m20-1223

Klouda CB, Stone WL (2020) Oxidative stress, proton fluxes, and chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine treatment for COVID-19. Antioxidants (Basel) 9(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9090894

Lamballerie XD, Boisson V, Reynier J-C, Enault S, Charrel RN, Flahault A, Roques P, Grand RL (2008) On chikungunya acute infection and chloroquine treatment. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 8(6):837–840

Lammers AJJ, Brohet RM, Theunissen REP, Koster C, Rood R, Verhagen DWM, Brinkman K, Hassing RJ, Dofferhoff A, El Moussaoui R, Hermanides G, Ellerbroek J, Bokhizzou N, Visser H, van den Berge M, Bax H, Postma DF, Groeneveld PHP (2020) Early Hydroxychloroquine but not chloroquine use reduces ICU admission in COVID-19 patients. Int J Infect Dis 101:283–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.1460

Lamoureux F, Thomas C, Crafter C, Kumano M, Zhang F, Davies BR, Gleave ME, Zoubeidi A (2013) Blocked autophagy using lysosomotropic agents sensitizes resistant prostate tumor cells to the novel Akt inhibitor AZD5363. Clin Cancer Res 19(4):833–844. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-12-3114

Lazarczyk M, Favre M (2008) Role of Zn2+ ions in host-virus interactions. J Virol 82(23):11486–11494. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01314-08

Legssyer R, Josse C, Piette J, Ward RJ, Crichton RR (2003) Changes in function of iron-loaded alveolar macrophages after in vivo administration of desferrioxamine and/or chloroquine. J Inorg Biochem 94(1–2):36–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0162-0134(02)00633-5

Li C, Zhu X, Ji X, Quanquin N, Deng Y-Q, Tian M, Aliyari R, Zuo X, Yuan L, Afridi SK (2017) Chloroquine, a FDA-approved drug, prevents Zika virus infection and its associated congenital microcephaly in mice. EBioMedicine 24:189–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.09.034

Lin M-H, Moses DC, Hsieh C-H, Cheng S-C, Chen Y-H, Sun C-Y, Chou C-Y (2018) Disulfiram can inhibit MERS and SARS coronavirus papain-like proteases via different modes. Antivir Res 150:155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.12.015

Liu J, Cao R, Xu M, Wang X, Zhang H, Hu H, Li Y, Hu Z, Zhong W, Wang M (2020) Hydroxychloroquine, a less toxic derivative of chloroquine, is effective in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro. Cell Discov 6(1):16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41421-020-0156-0

Magwere T, Naik YS, Hasler JA (1997) Effects of chloroquine treatment on antioxidant enzymes in rat liver and kidney. Free Radic Biol Med 22(1-2):321–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00285-7

Marzi A, Reinheckel T, Feldmann H (2012) Cathepsin B & L are not required for ebola virus replication. PLoS Neglect Trop D 6(12)

Mehra MR, Desai SS, Ruschitzka F, Patel AN (2020) RETRACTED: Hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine with or without a macrolide for treatment of COVID-19: a multinational registry analysis. Lancet. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31180-6

Meyerowitz EA, Vannier AGL, Friesen MGN, Schoenfeld S, Gelfand JA, Callahan MV, Kim AY, Reeves PM, Poznansky MC (2020) Rethinking the role of hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19. FASEB J 34(5):6027–6037. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.202000919

Michaelides M, Stover NB, Francis PJ, Weleber RG (2011) Retinal toxicity associated with hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine: risk factors, screening, and progression despite cessation of therapy. Arch Ophthalmol 129(1):30–39. https://doi.org/10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.321

Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Levine B (2010) Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell 140(3):313–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.028

Murr C, Widner B, Wirleitner B, Fuchs D (2002) Neopterin as a marker for immune system activation. Curr Drug Metab 3(2):175–187. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389200024605082

National Health Commission (2020) Diagnosis and treatment protocol for novel coronavirus pneumonia (Trial Version 7). Chin Med J 133(9):1087–1095

National Institute of Health (2020) Chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine with or without azithromycin. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/antiviral-therapy/chloroquine-or-hydroxychloroquine-with-or-without-azithromycin/clinical-data%2D%2Dchloroquine-or-hydroxychloroquine/. Accessed 5 Nov 2020

Ohkuma S, Poole B (1981) Cytoplasmic vacuolation of mouse peritoneal macrophages and the uptake into lysosomes of weakly basic substances. J Cell Biol 90(3):656–664. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.90.3.656

Paiva CN, Bozza MT (2014) Are reactive oxygen species always detrimental to pathogens? Antioxid Redox Signal 20(6):1000–1037. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2013.5447

Parhizgar AR, Tahghighi A (2017) Introducing new antimalarial analogues of chloroquine and amodiaquine: a narrative review. Iran J Med Sci 42(2):115–128

Paton NI, Lee L, Xu Y, Ooi EE, Cheung YB, Archuleta S, Wong G, Wilder-Smith A (2011) Chloroquine for influenza prevention: a randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 11(9):677–683. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70065-2

Peymani P, Yeganeh B, Sabour S, Geramizadeh B, Fattahi MR, Keyvani H, Azarpira N, Coombs KM, Ghavami S, Lankarani KB (2016) New use of an old drug: chloroquine reduces viral and ALT levels in HCV non-responders (a randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial). Can J Physiol Pharmacol 94(6):613–619. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjpp-2015-0507

Quiros Roldan E, Biasiotto G, Magro P, Zanella I (2020) The possible mechanisms of action of 4-aminoquinolines (chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine) against Sars-Cov-2 infection (COVID-19): a role for iron homeostasis? Pharmacol Res 158:104904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104904

Redmann M, Benavides GA, Berryhill TF, Wani WY, Ouyang X, Johnson MS, Ravi S, Barnes S, Darley-Usmar VM, Zhang J (2017) Inhibition of autophagy with bafilomycin and chloroquine decreases mitochondrial quality and bioenergetic function in primary neurons. Redox Biol 11:73–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2016.11.004

Riviere JH, Back DJ (1986) Inhibition of ethinyloestradiol and tolbutamide metabolism by quinoline derivatives in vitro. Chem Biol Interact 59(3):301–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0009-2797(86)80075-8

Roques P, Thiberville SD, Dupuis-Maguiraga L, Lum FM, Labadie K, Martinon F, Gras G, Lebon P, Ng LFP, de Lamballerie X, Le Grand R (2018) Paradoxical effect of chloroquine treatment in enhancing chikungunya virus infection. Viruses 10(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/v10050268

Rosendaal FR (2020) Review of: “Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial Gautret et al 2010, DOI:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949”. Int J Antimicrob Agents 56(1):106063–106063. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106063

Roy LD, Mazumdar M, Giri S (2008) Effects of low dose radiation and vitamin C treatment on chloroquine-induced genotoxicity in mice. Environ Mol Mutagen 49(6):488–495. https://doi.org/10.1002/em.20408

Sahu R, Kashyap P (2012) Genotoxic potential of some commonly used antimalarials: a review. Int J Pharm Sci Res 3(6):1569

Savarino A, Boelaert JR, Cassone A, Majori G, Cauda R (2003) Effects of chloroquine on viral infections: an old drug against today’s diseases? Lancet Infect Dis 3(11):722–727. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00806-5

Schroder K, Hertzog PJ, Ravasi T, Hume DA (2004) Interferon-gamma: an overview of signals, mechanisms and functions. J Leukoc Biol 75(2):163–189. https://doi.org/10.1189/jlb.0603252

Shalumashvili MA, Sigidin Ia A (1976) Cytogenetic effects of chloroquine in a culture of human lymphocytes. Biull Eksp Biol Med 82(7):879–881

Shimizu Y, Yamamoto S, Homma M, Ishida N (1972) Effect of chloroquine on the growth of animal viruses. Arch Gesamte Virusforsch 36(1):93–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01250299

Shin D, Mukherjee R, Grewe D, Bojkova D, Baek K, Bhattacharya A, Schulz L, Widera M, Mehdipour AR, Tascher G, Geurink PP, Wilhelm A, van der Heden van Noort GJ, Ovaa H, Muller S, Knobeloch KP, Rajalingam K, Schulman BA, Cinatl J, Hummer G, Ciesek S, Dikic I (2020) Papain-like protease regulates SARS-CoV-2 viral spread and innate immunity. Nature. 587:657–662. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2601-5

Skelton FS, Pardini RS, Heidker JC, Folkers K (1968) Inhibition of coenzyme Q systems by chloroquine and other antimalarials. J Am Chem Soc 90(19):5334–5336. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja01021a084

Slater AF, Cerami A (1992) Inhibition by chloroquine of a novel haem polymerase enzyme activity in malaria trophozoites. Nature 355(6356):167–169. https://doi.org/10.1038/355167a0

Spiro HM (1986) Chemotherapy of malaria. Second ed.: Edited by L. J. Bruce-Chwatt, with R. H. Black, C. J. Canfield, D. F. Clyde, W. Peters, and W. H. Wernsdorfer. 261 pp., 44 Swiss francs. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 1986. ISBN 92 4 1401273. Gastroenterology 91(4):1034. https://doi.org/10.5555/uri:pii:0016508586907249

Sugioka Y, Suzuki M, Sugioka K, Nakano M (1987) A ferriprotoporphyrin IX-chloroquine complex promotes membrane phospholipid peroxidation. A possible mechanism for antimalarial action. FEBS Lett 223(2):251–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-5793(87)80299-5

Sullivan DJ Jr (2017) Quinolines block every step of malaria heme crystal growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114(29):7483–7485. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1708153114

Sullivan DJ Jr, Gluzman IY, Russell DG, Goldberg DE (1996) On the molecular mechanism of chloroquine’s antimalarial action. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93(21):11865–11870. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.93.21.11865

Tan YW, Yam WK, Sun J, Chu JJH (2018) An evaluation of chloroquine as a broad-acting antiviral against hand, foot and mouth disease. Antivir Res 149:143–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.11.017

te Velthuis AJ, van den Worm SH, Sims AC, Baric RS, Snijder EJ, van Hemert MJ (2010) Zn(2+) inhibits coronavirus and arterivirus RNA polymerase activity in vitro and zinc ionophores block the replication of these viruses in cell culture. PLoS Pathog 6(11):e1001176. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1001176

Thabrew MI, Ioannides C (1984) Inhibition of rat hepatic mixed function oxidases by antimalarial drugs: selectivity for cytochromes P-450 and P-448. Chem Biol Interact 51(3):285–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2797(84)90154-6

Torrentino-Madamet M, Desplans J, Travaille C, Jammes Y, Parzy D (2010) Microaerophilic respiratory metabolism of plasmodium falciparum mitochondrion as a drug target. Curr Mol Med 10(1):29–46. https://doi.org/10.2174/156652410791065390

Touret F, de Lamballerie X (2020) Of chloroquine and COVID-19. Antivir Res 177:104762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104762

Tracey MDKJ, Cerami PDA (1994) Tumor necrosis factor: a pleiotropic cytokine and therapuetic target. Annu Rev Med 45(1):491–503. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.med.45.1.491

Tricou V, Minh NN, Van TP, Lee SJ, Farrar J, Wills B, Tran HT, Simmons CP (2010) A randomized controlled trial of chloroquine for the treatment of dengue in Vietnamese adults. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 4(8):e785. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0000785

Vaidya AB, Mather MW (2009) Mitochondrial evolution and functions in malaria parasites. Annu Rev Microbiol 63:249–267. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073424

van den Borne BE, Dijkmans BA, de Rooij HH, le Cessie S, Verweij CL (1997) Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine equally affect tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin 6, and interferon-gamma production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Rheumatol 24(1):55–60

Vessoni AT, Quinet A, Andrade-Lima LCD, Martins DJ, Garcia CCM, Rocha CRR, Vieira DB, Menck CFM (2016) Chloroquine-induced glioma cells death is associated with mitochondrial membrane potential loss, but not oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med 90:91–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.11.008

Vezmar M, Georges E (1998) Direct binding of chloroquine to the multidrug resistance protein (MRP): possible role for MRP in chloroquine drug transport and resistance in tumor cells. Biochem Pharmacol 56(6):733–742. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-2952(98)00217-2

Vezmar M, Georges E (2000) Reversal of MRP-mediated doxorubicin resistance with quinoline-based drugs. Biochem Pharmacol 59(10):1245–1252. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00270-7

Vigerust DJ, McCullers JA (2007) Chloroquine is effective against influenza A virus in vitro but not in vivo. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 1(5–6):189–192

Villinger F, Rollin PE, Brar SS, Chikkala NF, Winter J, Sundstrom JB, Zaki SR, Swanepoel R, Ansari AA, Peters CJ (1999) Markedly elevated levels of interferon (IFN)-γ, IFN-α, interleukin (IL)-2, IL-10, and tumor necrosis factor-α associated with fatal Ebola virus infection. J Infect Dis 179(Supplement_1):S188–S191. https://doi.org/10.1086/514283

Vincent MJ, Bergeron E, Benjannet S, Erickson BR, Rollin PE, Ksiazek TG, Seidah NG, Nichol ST (2005) Chloroquine is a potent inhibitor of SARS coronavirus infection and spread. Virol J 2(1):69

Wagener FA, Volk HD, Willis D, Abraham NG, Soares MP, Adema GJ, Figdor CG (2003) Different faces of the heme-heme oxygenase system in inflammation. Pharmacol Rev 55(3):551–571. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.55.3.5

Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L, Yang X, Liu J, Xu M, Shi Z, Hu Z, Zhong W, Xiao G (2020) Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res 30(3):269–271. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0

Wessels I, Rolles B, Rink L (2020) The potential impact of zinc supplementation on COVID-19 pathogenesis. Front Immunol 11:1712. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.01712

White NJ (1996) The treatment of malaria. N Engl J Med 335(11):800–806. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199609123351107

Winzeler EA (2008) Malaria research in the post-genomic era. Nature 455(7214):751–756

World Health Organization (2020) “Solidarity” clinical trial for COVID-19 treatments. UPDATE: solidarity trial reports interim results. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/global-research-on-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov/solidarity-clinical-trial-for-covid-19-treatments

Xue J, Moyer A, Peng B, Wu J, Hannafon BN, Ding W-Q (2014) Chloroquine is a zinc ionophore. PLoS One 9(10):e109180–e109180. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0109180

Yan Y, Zou Z, Sun Y, Li X, Xu K-F, Wei Y, Jin N, Jiang C (2013) Anti-malaria drug chloroquine is highly effective in treating avian influenza A H5N1 virus infection in an animal model. Cell Res 23(2):300–302. https://doi.org/10.1038/cr.2012.165

Yang Z-Y, Huang Y, Ganesh L, Leung K, Kong W-P, Schwartz O, Subbarao K, Nabel GJ (2004) pH-dependent entry of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus is mediated by the spike glycoprotein and enhanced by dendritic cell transfer through DC-SIGN. J Virol 78(11):5642–5650. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.78.11.5642-5650.2004

Yu H, Zhou Y, Lind SE, Ding W-Q (2009) Clioquinol targets zinc to lysosomes in human cancer cells. Biochem J 417(1):133–139. https://doi.org/10.1042/BJ20081421

Zheng J, Zhang X-X, Yu H, Taggart JE, Ding W-Q (2012) Zinc at cytotoxic concentrations affects posttranscriptional events of gene expression in cancer cells. Cell Physiol Biochem 29(1-2):181–188. https://doi.org/10.1159/000337599

Zoroddu MA, Medici S, Ledda A, Nurchi VM, Lachowicz JI, Peana M (2014) Toxicity of nanoparticles. Curr Med Chem 21(33):3837–3853. https://doi.org/10.2174/0929867321666140601162314

Zoroddu MA, Aaseth J, Crisponi G, Medici S, Peana M, Nurchi VM (2019) The essential metals for humans: a brief overview. J Inorg Biochem 195:120–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2019.03.013

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MP, AG, SN, AM, and AGB contributed to data acquisition and wrote the first version of the manuscript. RL and MP supported the conception and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. GB contributed to the acquisition of data, drafting and revising the manuscript, and coordinated the project. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gasmi, A., Peana, M., Noor, S. et al. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19: the never-ending story. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 105, 1333–1343 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-021-11094-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-021-11094-4