Abstract

Bicyclus butterflies are key species for studies of wing pattern development, phenotypic plasticity, speciation and the genetics of Lepidoptera. One of the key endosymbionts in butterflies, the alpha-Proteobacterium Wolbachia pipientis, is affecting many of these biological processes; however, Bicyclus butterflies have not been investigated systematically as hosts to Wolbachia. In this study, we screen for Wolbachia infection in several Bicyclus species from natural populations across Africa as well as two laboratory populations. Out of the 24 species tested, 19 were found to be infected, and no double infection was found, but both A- and B-supergroup strains colonise this butterfly group. We also show that many of the Wolbachia strains identified in Bicyclus butterflies belong to the ST19 clonal complex. We discuss the importance of our results in regard to routinely screening for Wolbachia when using Bicyclus butterflies as the study organism of research in eco-evolutionary biology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Current estimates suggest that up to 70% of all insect species in the world may live in intimate relation with intracellular micro-organisms [1, 2]. The outcome of such symbiotic associations, or endosymbiosis, ranges from mutualistic and beneficial to both the host and the microbe, to parasitic and detrimental to the host [3]. The bacterial species Wolbachia pipientis Hertig, 1936 [4], is one of the most common and best-studied endosymbionts found in insects. This maternally transmitted alpha-Proteobacterium selfishly promotes its own fitness by manipulating several aspects of its host’s biology [5]. The many potential distortions of the host’s fitness include the manipulation of its reproductive system [5] and of various life-history traits, such as fecundity [6], dispersal [7] and resistance to stresses caused by pathogens or the environment [8]. In Drosophila simulans for example, the Wolbachia strain wRi causes karyogamy failure and the arrest of early embryonic development of the offspring, when Wolbachia-free female flies are mated with Wolbachia-infected males [9]. However, at the same time, this bacterial strain protects the infected flies from viral infections [10]. By promoting its own fitness, through increasing the fitness of the infected host lines compared to uninfected ones, Wolbachia has the potential to act as a key player in the ecology and evolution of its hosts.

Butterflies and moths have long fascinated and attracted the attention of entomologists, both professionals and amateurs. They are generally easily identified compared to many other insect groups, thus facilitating the documentation of their habits and behaviors in natural environments. Furthermore, Lepidoptera often have relatively short life-cycles and high fecundity, and many species can be reared continuously in laboratory environments, thus making their use for large-scale experiments feasible. Finally, with recent development of molecular techniques, the study of insect genetics and genomics is no longer restricted to the Drosophila scientific community. The full genomes of 36 Lepidoptera are now publicly available (see for example [11,12,13,14,15]), and more are in preparation or partially sequenced (lepbase.org [16]). The availability of these new tools combined with our extended knowledge of gene to life-history traits, gained from both laboratory and field-based studies, makes many Lepidoptera species suitable model organisms for ecology and evolutionary studies.

There are over 100 species in the butterfly genus Bicyclus (Nymphalidae) [17]. Many species have distinct seasonal morphs mediated through environmentally induced plasticity. These seasonal phenotypes are characterised by variations in wing patterns [18, 19], pheromone compounds [20] and various life-history traits [21, 22]. Oliver et al. [23] have, for example, characterised different expression levels for several genes involved in the regulation of the eyespot wing patterns between B. anynana specimens developing in different environmental conditions, while Macias-Munoz et al. [24] have shown that sexes and seasonal morphs differentially express several other genes involved in insect vision. Combined together, these results suggest that the environment may play an important role in both mate recognition and choice in Bicyclus. The imminent completion of the B. anynana full genome sequencing project (lepbase.org) will certainly lead to an increased number of studies further investigating the consequences of seasonality in the evolutionary history of this and other Bicyclus species.

Despite the current wealth of eco-evolutionary studies on Bicyclus butterflies, and the fact that Wolbachia is a symbiont of many butterfly species worldwide [25], we are unaware of a study identifying the bacterium as an endosymbiont of B. anynana, or of any other Bicyclus species. This knowledge gap currently clearly contrasts with our understanding of peculiar host-symbiont interactions in several related Nymphalidae butterflies. Wolbachia are for example present in various species of Heteropsis [26], a genus closely related to Bicyclus [27], and have also been associated with Coenonympha tullia [28], Maniola jurtina [29], Caligo telamonius [30] and many other butterfly species [25]. Although further studies are needed to fully characterise the effect of Wolbachia in their butterfly hosts, the currently available studies on symbiotic interaction in a few butterfly species already suggest that the effects from such infections can have profound consequences for the eco-evolutionary biology of their butterfly hosts. The Wolbachia strains infecting the butterflies Hypolimnas bolina and Acraea encedon, for example, kill the male progeny of infected female butterflies [31, 32], thus potentially limiting inbreeding and sibling resource competition in these species.

In this paper, we report on the results from a screening for presence of Wolbachia infections, and the diversity of the Wolbachia strains, in samples from natural populations of several Bicyclus species from across sub-Saharan Africa. The characterisation of these Wolbachia strains is based on the standardised use of the five multilocus sequence typing markers (MLSTs [33]), and the genetic marker wsp [34]. For the first time, we show that Wolbachia infections are common in Bicyclus species, and that the strain diversity within this host genus is relatively high. We discuss the potential implications of these results for future studies using Bicyclus butterflies as focal organisms.

Material and Method

Material

The Bicyclus genus represents a highly diverse genus of over 100 African butterfly species [17]. The majority of the species inhabits the rainforest zone, while others are found in the savannah regions [35]. The many strikingly morphologically similar species in the genus are often only distinguishable through the comparison of highly divergent wing scales called androconia, specialised structures at least partly linked to pheromone production and release [36].

In total, 200 specimens from 24 species across the genus Bicyclus were used in this study [17] (Table 1). To avoid phylogenetic bias, we included samples from all except one (ena-group) of the 16 species groups currently recognised in the genus [17]. Nineteen of the sampled species generally inhabit forest environments, but some will also tolerate dry forest environments, while the remaining five are generally found in savannah habitats. Most species were collected from wild populations between 2008 and 2012; however, B. anynana and B. safitza samples were collected in 2016 from matrilines that had been maintained for several generations in the laboratory. The samples of B. anynana originated from a stock of around 80 females collected in Malawi in 1988 and currently reared by many labs across the world. The samples of B. safitza come from a more recent stock established from ten females collected in Uganda in 2013. The species identities of our specimens were previously identified for the purpose of a phylogenetic study by Aduse-Poku et al. [17]. No species of Bicyclus are currently classified as threatened species, and all field-collected samples were collected with permission from governmental organisations in their countries of origin. For each species except one (see below), four to ten individuals were tested for infection by Wolbachia. Since we focused on the screening of samples from a range of locations (up to five when possible) for each species, we potentially maximised the chance of detecting infections as well as strain diversity per species, but not per population. Finally, since we had no prior knowledge with regards to the induction of male killing by endosymbionts in Bicyclus, we privileged female samples, but included males to make up the numbers when we did not have enough females available. Full details of all samples are available in Supplementary material Table S1.

Note that during the sequencing phase of this project, one of the species included in our original dataset, B. mandanes, was taxonomically revised and split in two distinct species [17]. This affected our data set that originally included ten samples of B. mandanes, with nine of these being moved to the newly discovered species B. collinsi and only one single specimen remained as B. mandanes.

Screening for Wolbachia infections

We separated the wings from the bodies of the Bicyclus specimens immediately after collection in the field, and the tissues were individually preserved in Eppendorf tubes filled with 99% ethanol, kept in a fridge until further dissection. For each butterfly, we extracted the DNA from thoracic tissues using Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Extraction Kit, and following the manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen, USA). We tested the quality of all DNA extracts by PCR amplification of the COI gene (primer pair LCO/HCO, [37]). We tested for Wolbachia infection by PCR using five MLST markers (multilocus sequence typing genes: coxA, fbpA, ftsZ, gatB and hcpA, using respective primers from [33], and the wsp gene (primer pairs 81F/691R [34]). All amplified sequences were deposited into GenBank (#KY658538-664).

Genotyping the Wolbachia strains

Amplicons from each MLST and the wsp genes were sequenced on an automated ABI 3730 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems™, USA). Both reverse and forward strand were sequenced for each sample. Sequences were manually curated using Geneious R6 (http://www.geneious.com [38]) for consistency between reverse and forward sequences of each sample. The lack of double nucleotide picks along the sequences supported single Wolbachia infection in our samples. All sequences were compared to the PubMLST database (http://pubmlst.org/wolbachia [33]) using BLASTn. New allelic profiles were manually curated, characterised and added to the PubMLST database. Note that we used Wolbachia primers previously designed by Baldo et al. [33] in non-optimised conditions, and failed to amplify all MLST loci for several strains, thus providing new evidence that the currently available tools are not optimum for a universal genotyping of the Wolbachia strains in Lepidoptera. For the purpose of this study, we assigned a full strain name when three or more of the MLST loci were fully sequenced, and a potential strain name when only two MLST loci were sequenced, but did not assign any strain name if only one MLST locus was sequenced, whether or not the wsp gene was sequenced.

Phylogeny

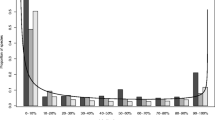

The Wolbachia phylogenetic trees were built using the online tree-building program Phylogeny.fr in the One-click mode with default settings [39]. In brief, the One-Click method builds a maximum likelihood tree using PhyML [40] with sequence alignment using MUSCLE [41, 42]. We used the coxA marker to build our main Wolbachia phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1), as this locus was amplified and sequenced for the largest number of Bicyclus samples and species. Similarly, we used the MLST sequences from each of the 13 strains that were fully characterised, to build the phylogenetic tree of these Wolbachia strain (Fig. S1). The respective MLST sequences from six additional Wolbachia strains (wBol2, wMel, wRi, wBol1, wPip and wBm; GenBank nos. AM999887, CP001391, AE017321, AE017196, EF025179–183, EF078895, AB474245–249, AB094382), previously characterised as belonging to the A-, B- or D-supergroups, were added to the trees. We rooted the trees using wBm as the outgroup.

Rooted phylogram based on the different allelic profiles of the coxA gene amplified from Bicyclus butterflies and six reference strains (wMel, wRi, wBol2, wPip, wBol1 and wBm), with PhyML aLRT-based branch support values. A, B and D refer to three Wolbachia supergroups. Branches are named after the host species names, and sample ID when necessary. The wBm strain from the parasitic nematode Brugia malayi was used as the outgroup. The Bicyclus hosts have been labelled according to their respective species groups (as defined in [17]) and show no clear pattern of congruence with the Wolbachia phylogeny

Statistics

Due to our restricted sample size in certain categories, we decided to independently test for sex and habitat effects on the Wolbachia infection status of these butterflies using chi-square tests.

Results

Prevalence and Penetrance

In total, 19 (79.2%) out of the 24 species tested were found infected by Wolbachia (N inf = 113 butterflies) (Table 1). Infection rates ranged from 10 to 100% depending on the species and the country of origin of the samples tested (Table 1). The infection rate did not differ between males (56.1%, N inf./tot. = 37/66) and females (56.7%, N inf./tot = 76/134) (χ 2 = 0.008, df = 1, P = 0.9299). Comparing samples from savannah- and forest-related habitats, there was a significantly higher infection ratio in samples from forest (64.7%, N inf./tot. = 99/153) compared to savannah (29.8%, N inf./tot = 14/47) (χ 2 = 17.838, df = 1, P = 0.0001). It should be noted that all samples from two of the savannah-adapted species (N = 20) originated from lab stocks were free of infections. Given their rearing conditions, they might not demonstrate a natural infection rate (see “Discussion” section). When these laboratory-reared samples are removed from our analysis, the difference between habitats is no longer significant (χ 2 = 1.623, df = 1, P = 0.2027). The dataset however becomes highly biased with almost all samples (153 out of 180) from forest species.

Phylogenetic Congruence

Amplification of the wsp and of all five MLST loci was not always successful, and therefore, a thorough phylogenetic analysis based on the concatenated sequences of all markers could not be completed. The results of our amplification efforts can be found in Table S1. The coxA locus successfully amplified for most of our Wolbachia-infected butterflies but 13 specimens. Visual comparative analysis of symbiotic strains versus host phylogenetic clustering shows no congruence between the phylogenies of the butterfly hosts and of their Wolbachia symbionts, with phylogenetically close Wolbachia strains being found in phylogenetically distant Bicyclus host species. This is true when we used either the coxA sequence only (Fig. S1) or the concatenated wsp and MLST sequences (Fig. S1) for building the Wolbachia phylogenies.

Wolbachia strain diversity

All strains except one were exclusively found in a single Bicyclus species each, the exception being strain ST19 that was found in five species (B. auricruda, B. collinsi, B. ignobilis, B. mandanes and B. vulgaris). Additionally, the within-host species symbiotic strain diversity was low, with generally a single strain detected per species. However, in six species more than one strain was detected. The highest diversity was found in B. auricruda and B. xeneas, where three separate strains were at least partially characterised in each species. We did not detect any double infection in any of our samples.

Notably, the three strains (one uncharacterised strain, wBaur_A and wBaur2_A/ST19) infecting B. auricruda fulgida were found at a single sample site (Ologbo Forest, Nigeria). In contrast, the three strains found in B. xeneas show a more geographical separation with strain wBxen_A found in Liberia, Ghana and Western Nigeria (Ologbo and Omo forests), strain wBxen2_A found in Liberia only and strain wBxen_B from Rhoko in Eastern Nigeria. Two strains were also found in the species B. evadne (wBeva_B and wBeva_A), and two strains were partially characterised in B. funebris (wBfun_B and one uncharacterised strain), B. pavonis (one uncharacterised strain and wBpav_B/ST423) and B. vulgaris (one uncharacterised strain and wBvul_A/ST19), again with different strains often being detected at the same sample sites.

Most of our B. xeneas specimens carry Wolbachia strains that can be grouped to the same clonal complex (STC-19), because these strains share at least three identical loci with ST19. The strains from the STC-19 were found in specimens collected from sites ranging from across the African rainforest belt (from Sapo, Liberia, through Ghana and Nigeria to Kibale in Uganda). This wide-ranging occurrence supports the findings of Ahmed et al. [25], which suggested that the strains from the STC-19 are capable of inter-familial, inter-superfamilial and inter-ordinal horizontal transmission. The strain ST19 was previously characterised from several other species of Lepidoptera, including Ephestia kuehniella, Aricia artaxerxes and Ornipholidotos peucetia, as well as various species of Hymenoptera and Coleoptera (pubmlst.org). Similarly, the strain ST187 found in B. jacksoni and the strain ST423 found in B. pavonis were both previously characterised from the endoparasitoid wasp Diaphorencyrtus aligarhensis, and an unspecified host species, respectively (pubmlst.org). All other strains, but not all allelic profiles of each marker, were new to the PubMLST database.

As often observed in Lepidoptera, Bicyclus butterflies serve as hosts to both A-supergroup Wolbachia strains (N A = 30, from eight host species) and/or B-supergroup Wolbachia strains (N B = 82, from 16 host species). Recombination is rampant in Wolbachia [43], and our dataset suggests past exchanges of loci within the A- and B-supergroups (Table S1). Both strains wBeva_A and wBing_A share the same allelic profile at the ftsZ locus, while all other loci are divergent; similarly, wBpav_B and wBtae_B only share an identical fbpA allelic profile (Fig. S2). In contrast, we did not find any recombining strains, with an admixture of loci from the A- and B-supergroups. Note that for the gatB locus sequenced from one sample of the B. nobilis species, the resulting sequence grouped in the A-supergroup, while all other locus groups are in the B-supergroup; however, our consecutive attempts at re-sequencing this particular locus failed, therefore we do not consider this as a reliable result. In contrast, we found both A- and B-supergroup strains in separate specimens from three species (B. auricruda, B. evadne and B. xeneas). Notably, both supergroups were found in similar proportions in males (N a/b = 6/31) and females (N a/b = 24/51) (χ 2 = 3.1475, df = 1, P = 0.0760).

Discussion

Wolbachia is highly prevalent in the butterfly genus Bicyclus, with penetrance of the infection in each species and population often reaching 50% or higher. We detected the presence of the endosymbiotic bacterium Wolbachia in 113 butterflies (56.5%) from 19 (79.2%) of the 24 tested species of the genus Bicyclus. However, because not all our samples successfully amplified with each marker used, and due to our relatively small sample size for each butterfly species and population, it is possible that we are still under-estimating the true prevalence and diversity of Wolbachia in the genus Bicyclus. Notably, the absence of Wolbachia in the laboratory stocks of B. anynana and B. safitza could also be the outcome of directed selection due to the artificial long-term rearing environment, which may have for unknown reasons favoured uninfected matrilines. In contrast, the potential occurrence of the horizontal transfer of Wolbachia genes to the host genomes [44] may lead to an over-estimation of the prevalence of cytoplasmic Wolbachia in these butterflies. However, since nuclear copies of Wolbachia genes would evolve in a different way than cytoplasmic copies, we suggest that the same allelic profiles should not be found in highly divergent butterfly hosts, as we currently observe. Although none of the loci tested in this study were amplified from B. anynana samples, loci could be identified in the whole genome sequence of this host species by screening for genes that indicate transfer of Wolbachia genomic material to the host genome.

The strain diversity within each Bicyclus species is generally low, with three or fewer strains described in each host species. Populations of B. xeneas were infected by different Wolbachia strains, correlating to a subspecific border in this species, with the Western samples (B. xeneas occidentalis) carrying Wolbachia strains from the A-supergroup ST19-clonal complex, while the Eastern sample (B. x. xeneas, Rhoko population) carries a yet unidentified, but clearly different, strain from the B-supergroup. In contrast, the strain diversity within the genus Bicyclus appears relatively high, with 20 strains fully or partially described in this study. In contrast to recent studies showing that the strain ST41 might be the core strain or ancestral strain of Wolbachia in Lepidoptera [25, 43, 45], our study would suggest that ST19 might play such a role in the Bicyclus clade. Only two of the Wolbachia strains described in Bicyclus share at least one locus with ST41 (coxA:14 and fbpA:4 are found in ST423 from B. pavonis, and fbpA:4 is also found in the strain infecting B. taenias), while six species carry a strain related to the ST19 clonal complex. These results challenge the idea of worldwide similarity of Lepidopteran Wolbachia suggested by Ahmed et al. [25], and Ilinsky and Kosterin [43]; however, further analyses of Wolbachia diversity in the entire Bicyclus clade are needed.

Only two strains, ST19 and wBeph_B, were found to infect either closely related (B. manandes and B. collinsi) or highly divergent host species (B. ephorus and B. sangmelinae), respectively. The fact that phylogenetically diverse Bicyclus species share similar Wolbachia strain supports a lack of congruence between the hosts and the bacterial strain phylogenies. The acquisition of Wolbachia in many Bicyclus butterflies therefore potentially happens through horizontal transfer between host species. The mechanisms driving the horizontal transfer of cytoplasmic Wolbachia between host species are yet poorly understood. Horizontal transfer of Wolbachia was previously suggested between Diptera species feeding on the same mushroom species [46], or between interacting species within food webs (e.g. host-parasitoid food webs [47]). Many Bicyclus species are found in sympatry in similar natural habitats, exhibit similar wing patterns and share relatively similar host plants for feeding and oviposition. Thus, although there are currently no documented records of naturally occurring interspecies hybridisation between Bicyclus species, such events may occur more often than previously thought or observed. Interestingly, various strains belonging to the ST19-clonal complex and found in highly divergent Bicyclus species were also previously characterised from other butterfly and insect species, including parasitoid wasps. These particular strains may be highly mobile not only between Bicyclus species but also at a larger scale between various insect species. A more extensive analysis of the Wolbachia infections occurring in the Bicyclus butterflies and their associated parasitoids would further inform on the potential origins and transfer routes of these symbionts in the wild populations of the butterfly hosts. Similarly, future studies with larger number of samples, especially with more males and species from the savannah habitat, should more accurately identify whether sex, habitat or the interaction of the two factors may also correlate with the prevalence of Wolbachia in these Bicyclus species.

To our knowledge, this study is the first evidence of the presence of Wolbachia in Bicyclus butterflies. Our results provide complementary information to studies that have detected Wolbachia in various other butterfly species [25], as well as a novel angle of investigation to eco-evolutionary research conducted using Bicyclus butterflies as model organisms. Wolbachia is particularly well-known for its ability to alter its host reproductive system, either through cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI), feminisation, or male killing (MK). The tropical butterfly H. bolina is infected by a Wolbachia strain inducing MK, a type of symbiont-induced early death of the male progeny of infected females. In the beginning of the century, some populations of H. bolina exhibited a sex ratio highly biased in favour of females [48]. The pressures from male rareness in these populations were such that the host species evolved to suppress the symbiont-induced MK phenotype [49, 50], and to re-establish a balanced sex/ratio [51]. Similarly, the African butterfly A. encedon carries another MK Wolbachia strain. Instead of evolving a suppressor gene like in H. bolina, this species shows altered mating behaviors [32]. In uninfected populations of A. encedon, the females are the choosing sex visiting hill-topping swarms of males, while in Wolbachia-infected populations, a sex role reversal is observed, and males chose between hill-topping females [32]. In most Bicyclus species tested, we showed that both male and female specimens could be infected by Wolbachia, either suggesting that the symbiotic strains do not induce MK, or that these butterfly species have evolved to repress the MK phenotype.

Furthermore, Wolbachia can also affect various life-history traits of its host, including viral protection in flies and mosquitoes [10, 52], mate recognition in Drosophila flies [53], sex determination in Pieridae butterflies [54] and terrestrial isopods [55, 56], ovarian development in Hymenoptera [57,58,59] and Nematodes [60] and many more traits in various other insect species. Although research using Bicyclus butterflies first focused on the evolution of developmental plasticity, these butterflies are now commonly considered as model organisms for studies in various eco-evolutionary processes [61]. Bicyclus anynana, for example, is used to investigate the underlying mechanisms of phenotypic variation and seasonal polyphenism (e.g. using diversity in wing patterns, morphology and other life-history traits [62]), of speciation (e.g. using phylogenetic analyses of almost 100 species [17], or through host plant preference and mate choice experiments [63]), of inbreeding depression [64] and of aging [21]. Whether the Wolbachia strains described in this study can alter any fitness trait of their respective host remains unknown. However, with the increasing number of studies now suggesting an important role of symbionts in many animal speciation events [65, 66], either through pre- or post-mating isolation mechanisms, it is not farfetched to propose Wolbachia as a potential serious key player in speciation processes within the Bicyclus clade. Developing an efficient detection method for Wolbachia in the Bicyclus clade will allow the fast and full characterisation of all divergent strains associated to these butterflies, which we were currently unable to achieve, and the detection of low titre infections that are often only detected through more time-consuming methods than PCR, such as qPCR or microscopy techniques. Only then might routine Wolbachia screenings in Bicyclus butterflies become universally feasible, and will enable us to comprehensively highlight the roles played by these potentially hidden factors in eco-evolutionary studies.

References

Stouthamer R, Breeuwer JAJ, Hurst GDD (1999) Wolbachia pipientis: microbial manipulator of arthropod reproduction Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 53:71–102

Ishikawa H (2003) Insect symbiosis: an introduction. In: Bourtzis K, Miller TA (eds) Insect symbiosis. CRC Press, N.Y, pp. 1–21

Moran NA (2006) Symbiosis Curr. Biol. 16:R866–R871

Hertig M (1936) The rickettsia, Wolbachia pipientis (Gen. Et SP.N.) and associated inclusions of the mosquito Culex pipiens Parasitology 28:453–486

O'Neill SL, Hoffman AA, Werren JH (1997) Influencial passengers, inherited microorganisms and arthropod reproduction. Oxford University Press Inc., NY,

Himler AG, Adachi-Hagimori T, Bergen JE, Kozuch A, Kelly SE, Tabashnik BE, Chiel E, Duckworth VE, Dennehy TJ, Zchori-Fein E, Hunter MS (2011) Rapid spread of a bacterial symbiont in an invasive Whitefly is driven by fitness benefits and female bias Science 332:254–256

Goodacre SL, Martin OY, Bonte D, Hutchings L, Woolley C, Ibrahim K, Thomas CFG, Hewitt GM (2009) Microbial modification of host long-distance dispersal capacity. Bmc Biol 7:32

Brownlie JC, Johnson KN (2009) Symbiont-mediated protection in insect hosts Trends Microbiol. 17:348–354

Callaini G, Dallai R, Riparbelli MG (1997) Wolbachia-induced delay of paternal chromatin condensation does not prevent maternal chromosomes from entering anaphase in incompatible crosses of Drosophila simulans J. Cell Sci. 110:271–280

Martinez J, Longdon B, Bauer S, Chan YS, Miller WJ, Bourtzis K, Teixeira L, Jiggins FM (2014) Symbionts commonly provide broad spectrum resistance to viruses in insects: a comparative analysis of Wolbachia strains. Plos Pathog 10(9): e1004369

Consortium TISG (2008) The genome of a lepidopteran model insect, the silkworm Bombyx mori Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 38:1036–1045. doi:10.1016/j.ibmb.2008.11.004

Ahola V, Lehtonen R, Somervuo P, Salmela L, Koskinen P, Rastas P, Valimaki N, Paulin L, Kvist J, Wahlberg N, Tanskanen J, Hornett EA, Ferguson LC, Luo SQ, Cao ZJ, de Jong MA, Duplouy A, Smolander OP, Vogel H, McCoy RC, Qian K, Chong WS, Zhang Q, Ahmad F, Haukka JK, Joshi A, Salojarvi J, Wheat CW, Grosse-Wilde E, Hughes D, Katainen R, Pitkanen E, Ylinen J, Waterhouse RM, Turunen M, Vaharautio A, Ojanen SP, Schulman AH, Taipale M, Lawson D, Ukkonen E, Makinen V, Goldsmith MR, Holm L, Auvinen P, Frilander MJ, Hanski I (2014) The Glanville fritillary genome retains an ancient karyotype and reveals selective chromosomal fusions in Lepidoptera. Nat Commun 5:4737

Cong Q, Borek D, Otwinowski Z, Grishin NV (2015) Skipper genome sheds light on unique phenotypic traits and phylogeny. Bmc Genomics 16:639

Cong Q, Borek D, Otwinowski Z, Grishin NV (2015) Tiger swallowtail genome reveals mechanisms for speciation and caterpillar chemical defense Cell Rep. 10:910–919

Derks MFL, Smit S, Salis L, Schijlen E, Bossers A, Mateman C, Pijl AS, de Ridder D, Groenen MAM, Visser ME, Megens HJ (2015) The genome of winter moth (Operophtera brumata) provides a genomic perspective on sexual dimorphism and phenology Genome Biol Evol 7:2321–2332

Challis RJ, Kumar S, Dasmahapatra KKK, Jiggins CD, Blaxter M (2017) Lepbase: the Lepidopteran genome database. bioRxiv 056994

Aduse-Poku K, Brakefield PM, Wahlberg N, Brattström O (2017) Expanded molecular phylogeny of the genus Bicyclus (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) shows the importance of increased sampling for detecting semi-cryptic species and highlights potentials for future studies Syst. Biodivers. 15:115–130

Brakefield PM, Gates J, Keys D, Kesbeke F, Wijngaarden PJ, Monteiro A, French V, Carroll SB (1996) Development, plasticity and evolution of butterfly eyespot patterns Nature 384:236–242

Lyytinen A, Brakefield PM, Lindstrom L, Mappes J (2004) Does predation maintain eyespot plasticity in Bicyclus anynana? P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci 271:279–283

Dion E, Monteiro A, Yew JY (2016) Phenotypic plasticity in sex pheromone production in Bicyclus anynana butterflies. Sci Rep-Uk 6:39002

Pijpe J, Brakefield PM, Zwaan BJ (2008) Increased life span in a polyphenic butterfly artificially selected for starvation resistance Am. Nat. 171:81–90

Molleman F, Ding JM, Wang JL, Brakefield PM, Carey JR, Zwaan BJ (2008) Amino acid sources in the adult diet do not affect life span and fecundity in the fruit-feeding butterfly Bicyclus anynana Ecol Entomol 33:429–438

Oliver JC, Ramos D, Prudic KL, Monteiro A (2013) Temporal gene expression variation associated with eyespot size plasticity in Bicyclus anynana. PLoS ONE 8(6): e65830

Macias-Munoz A, Smith G, Monteiro A, Briscoe AD (2016) Transcriptome-wide differential gene expression in Bicyclus anynana butterflies: female vision-related genes are more plastic Mol. Biol. Evol. 33:79–92

Ahmed MZ, Breinholt JW, Kawahara AY (2016) Evidence for common horizontal transmission of Wolbachia among butterflies and moths. Bmc Evol Biol 16:118

Linares MC, Soto-Calderon ID, Lees DC, Anthony NM (2009) High mitochondrial diversity in geographically widespread butterflies of Madagascar: a test of the DNA barcoding approach Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 50:485–495. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2008.11.008

Aduse-Poku K, Lees DC, Brattstrom O, Kodandaramaiah U, Collins SC, Wahlberg N, Brakefield PM (2016) Molecular phylogeny and generic-level taxonomy of the widespread palaeotropical ‘Heteropsis clade’ (Nymphalidae: Satyrinae: Mycalesina) Syst. Entomol. 41:717–731

Russell JA, Funaro CF, Giraldo YM, Goldman-Huertas B, Suh D, Kronauer DJ, Moreau CS, Pierce NE (2012) A veritable menagerie of heritable bacteria from ants, butterflies, and beyond: broad molecular surveys and a systematic review PLoS One 7:e51027. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051027

Cordaux R, Pichon S, Ling A, Perez P, Delaunay C, Vavre F, Bouchon D, Greve P (2008) Intense transpositional activity of insertion sequences in an ancient obligate endosymbiont Mol. Biol. Evol. 25:1889–1896. doi:10.1093/molbev/msn134

Shokralla S, Gibson JF, Nikbakht H, Janzen DH, Hallwachs W, Hajibabaei M (2014) Next-generation DNA barcoding: using next-generation sequencing to enhance and accelerate DNA barcode capture from single specimens Mol. Ecol. Resour. 14:892–901. doi:10.1111/1755-0998.12236

Hurst GDD, Jiggins FM, Majerus MEN (2003) Inherited microorganisms that selectively kill male hosts: the hidden players of insect evolution? In: Bourtzis K, Miller TA (eds) Insect symbiosis. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp. 177–198

Jiggins FM, Hurst GDD, Majerus MEN (2000) Sex-ratio-distorting Wolbachia causes sex-role reversal in its butterfly host P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci 267:69–73

Baldo L, Hotopp JCD, Jolley KA, Bordenstein SR, Biber SA, Choudhury RR, Hayashi C, Maiden MCJ, Tettelin H, Werren JH (2006) Multilocus sequence typing system for the endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis Appl Environ Microb 72:7098–7110

Zhou WG, Rousset F, O'Neill S (1998) Phylogeny and PCR-based classification of Wolbachia strains using wsp gene sequences P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci 265:509–515

Condamin M (1973) Monographie du genre Bicyclus (Lepidoptera, Satyridae). IFAN-Dakar, Dakar, p. 324

Bacquet PMB, Brattstrom O, Wang HL, Allen CE, Lofstedt C, Brakefield PM, Nieberding CM (2015) Selection on male sex pheromone composition contributes to butterfly reproductive isolation. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci 282:20142734

Folmer O, Hoch W, Lutz RA, Vrijehock RC (1994) DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 3:294–299

Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, Buxton S, Cooper A, Markowitz S, Duran C, Thierer T, Ashton B, Meintjes P, Drummond A (2012) Geneious basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data Bioinformatics 28:1647–1649

Dereeper A, Guignon V, Blanc G, Audic S, Buffet S, Chevenet F, Dufayard JF, Guindon S, Lefort V, Lescot M, Claverie JM, Gascuel O (2008) Phylogeny.fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist Nucleic Acids Res. 36:W465–W469

Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O (2010) New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0 Syst. Biol. 59:307–321

Edgar RC (2004) MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1792–1797

Edgar RC (2004) MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity Bmc Bioinformatics 5:1–19

Ilinsky Y, Kosterin OE (2017) Molecular diversity of Wolbachia in Lepidoptera: prevalent allelic content and high recombination of MLST genes Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 109:164–179. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2016.12.034

Dunning-Hotopp JC, Clark ME, Oliveira DCSG, Foster JM, Fischer P, Torres MC, Giebel JD, Kumar N, Ishmael N, Wang SL, Ingram J, Nene RV, Shepard J, Tomkins J, Richards S, Spiro DJ, Ghedin E, Slatko BE, Tettelin H, Werren JH (2007) Widespread lateral gene transfer from intracellular bacteria to multicellular eukaryotes Science 317:1753–1756

Salunkhe RC, Narkhede KP, Shouche YS (2014) Distribution and evolutionary impact of Wolbachia on butterfly hosts Indian J. Microbiol. 54:249–254. doi:10.1007/s12088-014-0448-x

Stahlhut JK, Desjardins CA, Clark ME, Baldo L, Russell JA, Werren JH, Jaenike J (2010) The mushroom habitat as an ecological arena for global exchange of Wolbachia Mol. Ecol. 19:1940–1952

Vavre F, Fleury F, Lepetit D, Fouillet P, Bouletreau M (1999) Phylogenetic evidence for horizontal transmission of Wolbachia in host-parasitoid associations Mol. Biol. Evol. 16:1711–1723

Charlat S, Engelstadter J, Dyson EA, Hornett EA, Duplouy A, Tortosa P, Davies N, Roderick GK, Wedell N, Hurst GDD (2006) Competing selfish genetic elements in the butterfly Hypolimnas bolina Curr. Biol. 16:2453–2458

Hornett EA, Duplouy AMR, Davies N, Roderick GK, Wedell N, Hurst GDD, Charlat S (2008) You can’t keep a good parasite down: evolution of a male-killer suppressor uncovers cytoplasmic incompatibility Evolution 62:1258–1263

Hornett EA, Moran B, Reynolds LA, Charlat S, Tazzyman S, Wedell N, Jiggins CD, Hurst GDD (2014) The evolution of sex ratio distorter suppression affects a 25 cM genomic region in the butterfly Hypolimnas bolina. Plos Genet 10(12): e1004822

Charlat S, Hornett EA, Fullard JH, Davies N, Roderick GK, Wedell N, Hurst GDD (2007) Extraordinary flux in sex ratio Science 317:214–214

Moreira LA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Jeffery JA, Lu GJ, Pyke AT, Hedges LM, Rocha BC, Hall-Mendelin S, Day A, Riegler M, Hugo LE, Johnson KN, Kay BH, McGraw EA, van den Hurk AF, Ryan PA, O'Neill SL (2009) A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with Dengue, Chikungunya, and Plasmodium Cell 139:1268–1278

Koukou K, Pavlikaki H, Kilias G, Werren JH, Bourtzis K, Alahiotisi SN (2006) Influence of antibiotic treatment and Wolbachia curing on sexual isolation among Drosophila melanogaster cage populations Evolution 60:87–96

Narita S, Kageyama D, Nomura M, Fukatsu T (2007) Unexpected mechanism of symbiont-induced reversal of insect sex: feminizing Wolbachia continuously acts on the butterfly Eurema hecabe during larval development Appl Environ Microb 73:4332–4341

Leclercq S, Theze J, Chebbi MA, Giraud I, Moumen B, Ernenwein L, Greve P, Gilbert C, Cordaux R (2016) Birth of a W sex chromosome by horizontal transfer of Wolbachia bacterial symbiont genome P Natl Acad Sci USA 113:15036–15041

Cordaux R, Bouchon D, Greve P (2011) The impact of endosymbionts on the evolution of host sex-determination mechanisms Trends Genet. 27:332–341

Dedeine F, Vavre F, Fleury F, Loppin B, Hochberg ME, Bouletreau M (2001) Removing symbiotic Wolbachia bacteria specifically inhibits oogenesis in a parasitic wasp P Natl Acad Sci USA 98:6247–6252

Dedeine F, Vavre F, Shoemaker DD, Bouletreau M (2004) Intra-individual coexistence of a Wolbachia strain required for host oogenesis with two strains inducing cytoplasmic incompatibility in the wasp Asobara tabida Evolution 58:2167–2174

Dedeine F, Bouletreau M, Vavre F (2005) Wolbachia requirement for oogenesis: occurrence within the genus Asobara (Hymenoptera, Braconidae) and evidence for intraspecific variation in A-tabida Heredity 95:394–400

Hoerauf A, Nissen-Pahle K, Schmetz C, Henkle-Duhrsen K, Blaxter ML, Buttner DW, Gallin MY, Al-Qaoud KM, Lucius R, Fleischer B (1999) Tetracycline therapy targets intracellular bacteria in the filarial nematode Litomosoides sigmodontis and results in filarial infertility J. Clin. Invest. 103:11–17

Brakefield PM, Beldade P, Zwaan BJ (2009) The African butterfly Bicyclus anynana: a model for evolutionary genetics and evolutionary developmental biology emerging model organisms: a laboratory manual. Vol.1. CSHL Press, Cold Spring Harbor. doi:10.1101/pdb.emo122

Beldade P, Brakefield PM (2002) The genetics and evo-devo of butterfly wing patterns Nat Rev Genet 3:442–452

Nieberding CM, Bacquet PMB, Brattstrom O, Wang HL, Allen CE, Lofstedt C, Brakefield PM (2014) Selection on male sex pheromone composition drives butterfly diversification Chem. Senses 39:105–105

Saccheri IJ, Lloyd HD, Helyar SJ, Brakefield PM (2005) Inbreeding uncovers fundamental differences in the genetic load affecting male and female fertility in a butterfly P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci 272:39–46

Bordenstein SR (2003) Symbiosis and the origin of species. In: Bourtzis K, Miller TA (eds) Insect Symbiosis. CRC Press LLC, Florida, pp. 283–304

Shropshire JD, Bordenstein SR (2016) Speciation by symbiosis: the microbiome and behavior MBio 7:e01785. doi:10.1128/mBio.01785-15

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Toshka Nyman for her help with the molecular work and Simon Martin for valuable feedback on a draft manuscript. The project was funded by the Academy of Finland (Grant No. 266021 to AD). Fieldwork was funded through grants from the Wenner-Gren Foundation and the Helge Ax:son Johnson’s Foundation (to OB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AD and OB designed the study, analyzed the data and wrote the paper. OB collected the butterfly samples. AD produced the molecular data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Fig S1

Rooted phylogram based on the concatenated sequences of the five MLST ( coxA, fbpA, ftsZ, gatB and hcpA ) markers from 13 Wolbachia strains fully characterised from Bicyclus butterflies, and six reference strains (wMel, wRi, wBol2, wPip, wBol1, and wBm), PhyML aLRT-based branch support values. A, B and D refer to three Wolbachia supergroups. Branches are named after the host species names, and sample ID when necessary. The wBm strain from the parasitic nematode Brugia malayi was used as outgroup. (GIF 78.3 kb).

Fig S2

Rooted phylograms based on the different allelic profiles of the (a) wsp, (b) fbpA, (c) ftsZ, (d) gatB and (e) hcpA Wolbachia marker characterised from Bicyclus butterflies, and six reference strains (wMel, wRi, wBol2, wPip, wBol1, and wBm), PhyML aLRT-based branch support values. A, B and D refer to three Wolbachia supergroups. The wBm strain from the parasitic nematode Brugia malayi was used as outgroup. (GIF 86 kb).

Table S1

Origin, sex, Wolbachia- infection status and the different allelic profiles for wsp, coxA, fbpA, ftsZ, gatB and hcpA Wolbachia genes from all specimens from the 24 species of Bicyclus butterflies investigated in this study. (−) no PCR amplification, (+) PCR amplification but failed sequencing. Allelic profiles in brackets are the closest matches to our sequences in the pubmlst.org database. (XLS 87 kb).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Duplouy, A., Brattström, O. Wolbachia in the Genus Bicyclus: a Forgotten Player. Microb Ecol 75, 255–263 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-017-1024-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-017-1024-9