Abstract

Purpose

To investigate whether the Paediatric Regulation has already succeeded in addressing the needs of the paediatric population both quantitatively with respect to paediatric development plans and trials, and qualitatively with respect to the content of the plans. The Paediatric Regulation No 1901/2006 entered into force in Europe on 26 January 2007, with the aim to improve the development of medicinal products, to address the lack of age-appropriate formulations and to provide information on efficacy, safety and dosing for the paediatric population. The Regulation requires applications for marketing authorisations to be accompanied by either a product-specific waiver or a paediatric investigation plan, to be agreed by the Paediatric Committee (PDCO) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

Methods

A retrospective analysis of the applications for Paediatric Investigation Plans (PIPs) and Waivers submitted to the EMA, from 2007 until end of 2009, was performed. The content of scientific opinions adopted by the Paediatric Committee was compared to the proposals submitted by industry, and the paediatric clinical trials registered in the European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Clinical Trials (EudraCT) database were examined.

Results

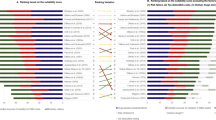

An increasing paediatric medicine development can be expected following the adoption of this legal framework. The highest number of PIPs was in the fields of endocrinology (13.4%), oncology (11%) and infectious (10.8%) and cardiovascular diseases (7.1%), but most therapeutic areas now benefit from paediatric development. A large number of PIPs include measures for the development of age-appropriate formulations (23%), and most include studies on dosing, efficacy and safety to cover the respective paediatric subsets, including the mostly neglected neonates (26%). In many proposals (38%), however, the PDCO had to request major modifications to the proposed PIPs to ensure that the results will meet the needs, in particular by requesting better methodology. The proportion of paediatric trials as a percentage of all clinical trials has moderately increased (from 8.2 to 9.4% of all trials), and this may reflect the fact that paediatric trials are generally deferred (82%) until after adult development.

Conclusions

This is the first analysis of the general impact of the Paediatric Regulation on the development of medicinal products in Europe. Three years after the implementation of the Paediatric Regulation, we were able to identify that the PIPs address the main gaps in knowledge on paediatric medicines. The key objective of the Paediatric Regulation, namely, the availability of medicines with age-appropriate information, is going to be achieved. It is clear also that modifications of the initial proposals as requested by the PDCO are necessary to ensure the quality of paediatric developments. The impact on the number of clinical trials performed remains modest at this point in time, and it will be of high interest to monitor this performance indicator, which will also inform us whether paediatric medicine research takes place in Europe or elsewhere.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Moore TJ, Weiss SR, Kaplan S, Blaisdell CJ (2002) Reported adverse drug events in infants and children under 2 years of age. Pediatrics 110:e53

Avenel S, Bomkratz A, Janaud DG, Danan C (2000) Incidence des prescriptions hors autorisation de mise sur le marché en réanimation néonatale. Arch Pediatr 7:143–147

Kozer E, Scolnik D, Keays T, Shi K, Luk T, Koren G (2002) Large errors in the dosing of medicines for children. N Engl J Med 346:1175–1176

Choonara I, Rieder MJ (2002) Drug toxicity and adverse drug reactions in children—a brief historical review. Paed Perinatal Drug Ther 5:12–18

Geiling EMK, Cannon PR (1938) Pathologic effects of elixir of sulphanilamide (diethylene glycol) poisoning. JAMA 111:919–926

Steinbrook R (2002) Testing medications in children. N Engl J Med 347:1462–1470

Schirm E, Tobi H, de Vries TW, Choonara I, Jong-van D, den Berg LTW (2003) Lack of appropriate formulations of medicines for children in the community. Acta Paediatr 92:1486–1489

ť Jong GW, Stricker BH, Choonara I, van den Anker JN (2002) Lack of effect of the European guidance on clinical investigation of medicines in children. Acta Paediatr 91(11):1233–1238

Davies EH, Ollivier CM, Saint Raymond A (2010) Paediatric investigation plans for pain: painfully slow! Eur J Clin Pharmacol 66(11):1091–1097 (Epub 7 Sep 2010)

Schreiner MS (2003) Paediatric clinical trials: redressing the imbalance. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2:949–961

Smyth R, Weindling AM (1999) Research in children: ethical and scientific aspects. Lancet 354(S2):21

Roberts R, Rodriguez W, Murphy D et al (2003) Paediatric drug labelling: improving the safety and efficacy of paediatric therapies. JAMA 7:905–911

Stephenson T (2005) How children’s responses to drugs differ from adults. Br J Clin Pharmacol 59:670–673

Bartels H (1983) Drug therapy in childhood: what has been done and what has to be done? Pediatr Pharmacol 3:131–143

Acknowledgements

TMO and ASR take responsibility for the whole content and have made substantial contributions to the conception, design and analysis and interpretation of the data and have drafted and critically revised the manuscript. ASR has supervised the work and given final approval of the manuscript. SFL and GG take public responsibility for part of the content, have made substantial contributions to acquisition of the data, and have critically revised the manuscript. We thank Gonzague Huet for building the paediatric database, Elin Haf Davies for critical proofreading and Paolo Tomasi for critical discussion and valuable remarks. We also thank the Paediatric Committee and the Paediatric Section of the European Medicines Agency whose work forms the basis for this investigation.

Disclaimer

The views presented in this article are those of the authors and should not be understood or quoted as being made on behalf of the European Medicines Agency and/or its scientific committees.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Olski, T.M., Lampus, S.F., Gherarducci, G. et al. Three years of paediatric regulation in the European Union. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 67, 245–252 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-011-0997-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-011-0997-4