Abstract

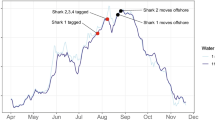

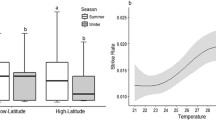

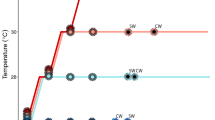

Tropical coral reef flats can be 3–4 °C warmer than surrounding deeper reef slopes, and some experience daily temperature fluctuations of up to 12 °C, which will be exacerbated as global temperatures continue to rise. Epaulette sharks (Hemiscyllium ocellatum), predominantly found on reef flats, may have evolved behavioural and/or physiological strategies to mitigate the effects of these dramatic temperature fluctuations. Here, juvenile sharks were acclimated, for at least 6 weeks, to average summer temperatures (28 °C) or predicted end-of-century summer temperatures (32 °C) to investigate the effects of elevated temperatures on growth, survival, and the use of movement to thermoregulate. In addition, sharks experience seasonal temperature changes; therefore, the upper critical thermal limits were determined for adult, wild sharks during both summer and winter months. We found that regardless of acclimation temperature, juveniles maintained the same food consumption rates (~ 5% body mass every other day), but for those living at 32 °C, this resulted in significantly decreased growth rates (body mass and total length). During winter months, maximum habitat temperatures (~ 24 °C) are far below adult sharks’ critical thermal limits (35.92 ± 0.21 °C). During summer months, maximum habitat temperatures (~ 35 °C) are closer to adult critical thermal limits (38.85 ± 0.31 °C). When estimating thermoregulatory behaviour of juvenile sharks maintained at 28 °C, those sharks examined in winter exhibited no thermoregulatory behaviour, while those examined in summer actively sought to control their thermal exposure, preferring 30.7 ± 1.04 °C (day) and 28.54 ± 0.75 °C (night). Furthermore, after acclimation to predicted end-of-century conditions, these same sharks behaviourally sought out 32.94 ± 0.46 °C (day) and 30.74 ± 0.68 °C (night); despite the cost of decreased growth and/or survival. Sharks maintained in control conditions had a mortality rate of 33% during the initial 90-day period of exposure, while mortality was 100% in those sharks exposed to elevated conditions. Ultimately, as ocean temperatures continue to rise, the distribution and abundance patterns for epaulette sharks and many other coral reef species are likely to change if trade-offs associated with acclimation outweigh the benefits of moving to more favourable habitats.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Angilletta MJ (2009) Thermal adaptation: a theoretical and empirical synthesis. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Armstrong JB, Schindler DE, Ruff CP, Brooks GT, Bentley KE, Torgersen CE (2013) Diel horizontal migration in streams: juvenile fish exploit spatial heterogeneity in thermal and trophic resources. Ecology 94:2066–2075. https://doi.org/10.1890/12-1200.1

Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) (2015a) Sea water temperature logger data at Lizard Island, Great Barrier Reef from 27 Oct 1995 to 06 Dec 2014, http://data.aims.gov.au/metadataviewer/faces/view.xhtml?uuid=b8fc8578-fef9-43fa-9483-222ade016c2b. Accessed 31 Oct 2015

Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) (2015b) Sea water temperature logger data at Heron Island, Great Barrier Reef from 24 Nov 1995 to 30 Mar 2015. http://data.aims.gov.au/metadataviewer/faces/view.xhtml?uuid=446a0e73-7c30-4712ddb-ba1fc29b8b9a. Accessed 25 Nov 2015

Becker CD, Genoway RG (1979) Evaluation of the critical thermal maximum for determining thermal tolerance of fresh water fish. Environ Biol Fish 4:245–256

Beitinger TL, Bennett WA, McCauley RW (2000) Temperature tolerances of North American freshwater fishes exposed to dynamic changes in temperature. Environ Biol Fish 58:237–275. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1007676325825

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B Stat Methodol 57:289–300

Bethea D, Hale L, Carlson J, Cortés E, Manire C, Gelsleichter J (2007) Geographic and ontogenetic variation in the diet and daily ration of the bonnethead shark, Sphyrna tiburo, from the eastern Gulf of Mexico. Mar Biol 152:1009–1020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-007-0728-7

Brett JR (1952) Temperature tolerance in young Pacific salmon, genus Oncorhynchus. J Fish Res Bd Can 9:265–323. https://doi.org/10.1139/f52-016

Brett JR (1971) Energetic responses of salmon to temperature. A study of some thermal relations in the physiology and freshwater ecology of sockeye salmon Oncorhynchus nerka. Am Zoo 11:99–113

Bulger AJ, Tremaine SC (1985) Magnitude of seasonal effects on heat tolerance in Fundulus heteroclitus. Physiol Zoo 58:197–204

Chave EHN, Randall HA (1971) Feeding behavior of the moray eel, Gymnothorax pictus. Copeia 1971:570–574. https://doi.org/10.2307/1442464

Cherry DS, Dickson KL, Cairns J Jr (1975) Temperatures selected and avoided by fish at various acclimation temperatures. J Fish Res Board Can 32:485–491. https://doi.org/10.1139/f75-059

Cherry DS, Dickson KL, Cairns J Jr, Stauffer JR (1977) Preferred, avoided, and lethal temperatures of fish during rising temperature conditions. J Fish Res Board Can 34:239–246. https://doi.org/10.1139/f77-035

Chisholm JJ, Barnes DD, Devereux MM (1996) Measurement and analysis of reef flat community metabolism at Lizard Island, Great Barrier Reef, Australia in March 1996, p 150

Clark DS, Green JM (1991) Seasonal variation in temperature preference of juvenile Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua), with evidence supporting an energetic basis for their diel vertical migration. Can J Zoo 69:1302–1307. https://doi.org/10.1139/z91-183

Cocherell DE, Fangue NA, Klimley PA, Cech JJ (2014) Temperature preferences of hardhead Mylopharodon conocephalus and rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss in an annular chamber. Environ Biol Fish 97:865–873. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-013-0185-8

Collins M, Knutti R, Arblaster J, Dufresne J-L, Fichefet T, Friedlingstein P, Gao X, Gutowski W, Johns T, Krinner G (2013) Long-term climate change: projections, commitments and irreversibility. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Coutant CC (1977) Compilation of temperature preference Ddata. J Fish Res Bd Can 34:739–745. https://doi.org/10.1139/f77-115

Depczynski M, Bellwood DR (2003) The role of cryptobenthic reef fishes in coral reef trophodynamics. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 256:183–191

Economakis AE, Lobel PS (1998) Aggregation behavior of the grey reef shark, Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos, at Johnston Atoll, central Pacific Ocean. Environ Biol Fish 51:129–139

Fry FEJ (1971) The effect of environmental factors on the physiology of fish. In: Hoar WS, Randall DJ (eds) Fish physiology. Academic, New York, pp 1–98

Fry FEJ, Hart JS (1948) Cruising speed of goldfish in relation to water temperature. J Fish Board Can 7:169–175

Furey NB, Dance MA, Rooker JR (2013) Fine-scale movements and habitat use of juvenile southern flounder Paralichthys lethostigma in an estuarine seascape. J Fish Biol 82:1469–1483. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.12074

Furukawa S, Tsuda Y, Nishihara GN, Fujioka K, Ohshimo S, Tomoe S, Nakatsuka N, Kimura H, Aoshima T, Kanehara H, Kitagawa T, Chiang W-C, Nakata H, Kawabe R (2014) Vertical movements of Pacific bluefin tuna (Thunnus orientalis) and dolphinfish (Coryphaena hippurus) relative to the thermocline in the northern East China Sea. Fish Res 149:86–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2013.09.004

Gardiner NM, Munday PL, Nilsson GE (2010) Counter-gradient variation in respiratory performance of coral reef fishes at elevated temperatures. PLoS One 5:e13299. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013299

Gehrke PC, Fielder DR (1988) Effects of temperature and dissolved oxygen on heart rate, ventilation rate and oxygen consumption of spangled perch, Leiopotherapon unicolor (Günther 1859), (Percoidei, Teraponidae). J Comp Phys B 157:771–782. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00691008

Gervais C, Mourier J, Rummer J (2016) Developing in warm water: irregular colouration and patterns of a neonate elasmobranch. Mar Biodivers 4:1–2

Gruber SH, De Marignac JR, Hoenig JM (2001) Survival of juvenile lemon sharks at Bimini, Bahamas, estimated by mark–depletion experiments. Trans Am Fish Soc 130:376–384

Guderley H, Gawlicka A (1992) Qualitative modification of muscle metabolic organization with thermal acclimation of rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss. Fish Physiol Biochem 10:123–132

Habary A, Johansen JL, Nay TJ, Steffensen JF, Rummer JL (2016) Adapt, move or die—how will tropical coral reef fishes cope with ocean warming? Glob Change Biol. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13488

Harborne AR (2013) The ecology, behaviour and physiology of fishes on coral reef flats, and the potential impacts of climate change. J Fish Biol 83:417–447. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.12203

Healy TM, Schulte PM (2012) Factors affecting plasticity in whole-organism thermal tolerance in common killifish (Fundulus heteroclitus). J Comp Physiol B 182:49–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00360-011-0595-x

Heinrich DDU, Rummer JL, Morash AJ, Watson S-A, Simpfendorfer CA, Heupel MR, Munday PL (2014) A product of its environment: the epaulette shark (Hemiscyllium ocellatum) exhibits physiological tolerance to elevated environmental CO2. Conserv Physiol. https://doi.org/10.1093/conphys/cou047

Heinrich DD, Watson S-A, Rummer JL, Brandl SJ, Simpfendorfer CA, Heupel MR, Munday PL (2015) Foraging behaviour of the epaulette shark Hemiscyllium ocellatum is not affected by elevated CO2. ICES J Mar Sci 7:633–640. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsv085

Heupel MR, Bennett MB (1998) Observations on the diet and feeding habits of the epaulette shark, Hemiscyllium ocellatum (Bonnaterre), on Heron Island Reef, Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Mar Freshw Res 49:753–756. https://doi.org/10.1071/MF97026

Heupel MR, Simpfendorfer CA (2002) Estimation of mortality of juvenile blacktip sharks, Carcharhinus limbatus, within a nursery area using telemetry data. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 59:624–632. https://doi.org/10.1139/f02-036

Johansen JL, Jones GP (2011) Increasing ocean temperature reduces the metabolic performance and swimming ability of coral reef damselfishes. Glob Change Biol 17:2971–2979. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02436.x

Johansen JL, Messmer V, Coker DJ, Hoey AS, Pratchett MS (2013) Increasing ocean temperatures reduce activity patterns of a large commercially important coral reef fish. Glob Change Biol. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12452

Johansen JL, Pratchett MS, Messmer V, Coker DJ, Tobin AJ, Hoey AS (2015) Large predatory coral trout species unlikely to meet increasing energetic demands in a warming ocean. Sci Rep 5(1):13830. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep13830

Johnson MS, Kraver DW, Renshaw GMC, Rummer JL (2016) Will ocean acidification affect the early ontogeny of a tropical oviparous elasmobranch (Hemiscyllium ocellatum)? Conserv Physiol. https://doi.org/10.1093/conphys/cow003

Killen SS (2014) Growth trajectory influences temperature preference in fish through an effect on metabolic rate 83:1513–1522. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12244

Kline DI, Teneva L, Hauri C, Schneider K, Miard T, Chai A, Marker M, Dunbar R, Caldeira K, Lazar B, Rivlin T, Mitchell BG, Dove S, Hoegh-Guldberg O (2015) Six month in situ high-resolution carbonate chemistry and temperature study on a coral reef flat reveals asynchronous pH and temperature anomalies. PLoS One 10:e0127648. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127648

Lombardi-Carlson LA, Cortes E, Parsons GR, Manire CA (2003) Latitudinal variation in life-history traits of bonnethead sharks, Sphyrna tiburo, (Carcharhiniformes : Sphyrnidae) from the eastern Gulf of Mexico. Mar Freshw Res 54:875–883. https://doi.org/10.1071/MF03023

Lough JM (1999) Sea surface temperatures on the Great Barrier Reef: a contribution to the study of coral bleaching. Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, Townsville

Lutterschmidt WI, Hutchison VH (1997) The critical thermal maximum: history and critique. Can J Zoo 75:1561–1574. https://doi.org/10.1139/z97-783

Marine KR, Cech JJ (2004) Effects of high water temperature on growth, smoltification, and predator avoidance in juvenile Sacramento River Chinook salmon. N Am J Fish Manage 24:198–210. https://doi.org/10.1577/M02-142

Martins EG, Hinch SG, Cooke SJ, Patterson DA (2012) Climate effects on growth, phenology, and survival of sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka): a synthesis of the current state of knowledge and future research directions. Rev Fish Biol Fisher 22:887–914. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-012-9271-9

McLeod IM, McCormick MI, Munday PL, Clark TD, Wenger AS, Brooker RM, Takahashi M, Jones GP (2015) Latitudinal variation in larval development of coral reef fishes: implications of a warming ocean. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 521:129–141

Meekan M, Fuiman L, Davis R, Berger Y, Thums M (2015) Swimming strategy and body plan of the world’s largest fish: implications for foraging efficiency and thermoregulation. Front Mar Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2015.00064

Munday PL (2014) Transgenerational acclimation of fishes to climate change and ocean acidification. F1000prime reports 6

Munday P, Kingsford M, O’Callaghan M, Donelson J (2008) Elevated temperature restricts growth potential of the coral reef fish Acanthochromis polyacanthus. Coral Reefs 27:927–931. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-008-0393-4

Murray CS, Malvezzi A, Gobler CJ, Baumann H (2014) Offspring sensitivity to ocean acidification changes seasonally in a coastal marine fish. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 504:1–11

Nay T, Johansen J, Habary A, Steffensen J, Rummer J (2015) Behavioural thermoregulation in a temperature-sensitive coral reef fish, the five-lined cardinalfish (Cheilodipterus quinquelineatus). Coral Reefs. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-015-1353-4

Neer JA, Rose KA, Cortes E (2007) Simulating the effects of temperature on individual and population growth of Rhinoptera bonasus: a coupled bioenergetics and matrix modeling approach. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 329:211–223

Nilsson GE, Ostlund-Nilsson S (2004) Hypoxia in paradise: widespread hypoxia tolerance in coral reef fishes. Proc R Soc B 271:S30–S33. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2003.0087

Noyola J, Caamal-Monsreal C, Díaz F, Re D, Sánchez A, Rosas C (2013) Thermopreference, tolerance and metabolic rate of early stages juvenile Octopus maya acclimated to different temperatures. J Therm Biol 38:14–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2012.09.001

Paladino FV, Spotila JR, Schubauer JP, Kowalski KT (1980) The critical thermal maximum a technique used to elucidate physiological stress and adaptation in fishes. Rev Can Biol 39:115–122

Parsons G (1993) Geographic variation in reproduction between two populations of the bonnethead shark, Sphyrna tiburo. Environ Biol Fish 38:25–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00842901

Payne EJ, Rufo KS (2012) Husbandry and growth rates of neonate epaulette sharks, Hemiscyllium ocellatum in captivity. Zoo Biol 31:718–724. https://doi.org/10.1002/zoo.20426

Petersen MF, Steffensen JF (2003) Preferred temperature of juvenile Atlantic cod Gadus morhua with different haemoglobin genotypes at normoxia and moderate hypoxia. J Exp Biol 206:359–364. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.00111

Pistevos JCA, Nagelkerken I, Rossi T, Olmos M, Connell SD (2015) Ocean acidification and global warming impair shark hunting behaviour and growth. Sci Rep 5:16293. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep16293

Pörtner HO, Farrell AP (2008) Physiology and climate change. Science 322:690–692

Pörtner HO, Peck MA (2010) Climate change effects on fishes and fisheries: towards a cause-and-effect understanding. J Fish Biol 77:1745–1779. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.2010.02783.x

Potts D, Swart P (1984) Water temperature as an indicator of environmental variability on a coral reef. Limnol Oceanogr 29:504–516

Reavis RH (1997) The natural history of a monogamous coral-reef fish, Valenciennea strigata (Gobiidae): 1. Abundance, growth, survival and predation. Exp Biol Fish 49:239–246

Renshaw GMC, Kerrisk CB, Nilsson GE (2002) The role of adenosine in the anoxic survival of the epaulette shark, Hemiscyllium ocellatum. Comp Biochem Physiol A 131:133–141

Routley MH, Nilsson GE, Renshaw GMC (2002) Exposure to hypoxia primes the respiratory and metabolic responses of the epaulette shark to progressive hypoxia. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 131:313–321

Rummer JL, Couturier CS, Stecyk JAW, Gardiner NM, Kinch JP, Nilsson GE, Munday PL (2014) Life on the edge: thermal optima for aerobic scope of equatorial reef fishes are close to current day temperatures. Glob Change Biol 20:1055–1066. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12455

Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B (2012) Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 9:676–682

Schmidt-Nielson K (1990) Animal physiology: adaptation and environment. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Sims DW, Wearmouth VJ, Genner MJ, Southward AJ, Hawkins SJ (2004) Low-temperature-driven early spawning migration of a temperate marine fish. J Anim Ecol 73:333–341. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0021-8790.2004.00810.x

Tewksbury JJ, Huey RB, Deutsch CA (2008) Putting the heat on tropical animals. Science 320:1296–1297. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1159328

Vergés A, Steinberg PD, Hay ME, Poore AGB, Campbell AH, Ballesteros E, Heck KL, Booth DJ, Coleman MA, Feary DA, Figueira W, Langlois T, Marzinelli EM, Mizerek T, Mumby PJ, Nakamura Y, Roughan M, van Sebille E, Gupta AS, Smale DA, Tomas F, Wernberg T, Wilson SK (2014) The tropicalization of temperate marine ecosystems: climate-mediated changes in herbivory and community phase shifts. Proc R Soc B. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.0846

West J, Carter S (1990) Observations on the development and growth of the epaulette shark Hemiscyllium ocellatum (Bonnaterre) in captivity. J Aquaric Aquatic Sci 5:111–117

Wise G, Mulvey JM, Renshaw GMC (1998) Hypoxia tolerance in the epaulette shark (Hemiscyllium ocellatum). J Exp Zoo 281:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-010X(19980501)281:1%3c1:AID-JEZ1%3e3.0.CO;2-S

Zhang Y, Kieffer JD (2014) Critical thermal maximum (CTmax) and hematology of shortnose sturgeons (Acipenser brevirostrum) acclimated to three temperatures. Can J Zoo 92:215–221. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjz-2013-0223

Acknowledgements

We want to thank SeaWorld, Gold Coast for donating sharks and D. Kraver and M. Johnson for rearing embryos. Additionally, thanks are due to the staff of the Marine and Aquatic Research Facilities Unit (MARFU) at James Cook University for help with infrastructure and logistical support, as well as the Heron Island staff for their support in the field. This work was supported by an Australian Research Council (ARC) Super Science Fellowship, ARC Early Career Discovery Award, and ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies research allocation to J. L. R. In addition, this work was funded in part by a Griffith University (Gold Coast) Climate Change Response Group research grant to G. R. and J. L. R.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical standards

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. Collection permit under the James Cook University accreditation and Marine Park permit, #G14/36697, from the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, was obtained.

Ethical approval

All animal care and experimental protocols used in this study were approved by James Cook University Animal Ethics Committee regulations (permit: A2089) and conducted according to the Australian Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes and the Queensland Animal Care and Protection Act 2001. This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of interest

No conflict interests exist. C. Gervais declares that he has no conflict of interest. T. Nay declares that she has no conflict of interest. G. Renshaw declares that she has no conflict of interest. J. Johansen declares that he has no conflict of interest. J. Steffensen declares that he has no conflict of interest. J. Rummer declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: A. Todgham.

Reviewed by Undisclosed experts.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gervais, C.R., Nay, T.J., Renshaw, G. et al. Too hot to handle? Using movement to alleviate effects of elevated temperatures in a benthic elasmobranch, Hemiscyllium ocellatum. Mar Biol 165, 162 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-018-3427-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-018-3427-7