Abstract

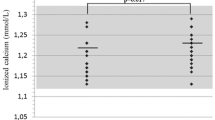

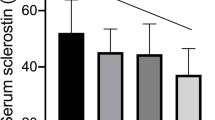

We tested the hypothesis that the levels of bone remodeling mediators may be altered in Prader–Willi syndrome (PWS). We assessed RANKL, OPG, sclerostin, DKK-1 serum levels, and bone metabolism markers in 12 PWS children (7.8 ± 4.3 years), 14 PWS adults (29.5 ± 7.2 years), and 31 healthy controls matched for sex and age. Instrumental parameters of bone mineral density (BMD) were also evaluated. Lumbar spine BMD Z-scores were reduced in PWS children (P < 0.01), reaching osteopenic levels in PWS adults. PWS patients showed lower 25(OH)-vitamin D serum levels than controls (P < 0.001). Osteocalcin was increased in PWS children but reduced in adults respect to controls (P < 0.005 and P < 0.01, respectively). RANKL levels were higher in both pediatric and PWS adults than controls (P < 0.004), while OPG levels were significantly reduced (P < 0.004 and P < 0.006, respectively). Sclerostin levels were increased in children (P < 0.04) but reduced in adults compared to controls (P < 0.01). DKK-1 levels did not show significant difference between patients and controls. In PWS patients, RANKL, OPG, and sclerostin significantly correlated with metabolic and bone instrumental parameters. Consistently, with adjustment for age, multiple linear regression analysis showed that BMD and osteocalcin were the most important predictors for RANKL, OPG, and sclerostin in children, and GH and sex steroid replacement treatment in PWS adults. We demonstrated the involvement of RANKL, OPG, and sclerostin in the altered bone turnover of PWS subjects suggesting these molecules as markers of bone disease and new potential pharmacological targets to improve bone health in PWS.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Butler MG, Manzardo AM, Forster JL (2016) Prader-Willi syndrome: clinical genetics and diagnostic aspects with treatment approaches. Curr Pediatr Rev 12:136–166

Lionti T, Reid SM, White SM, Rowell MM (2015) A population-based profile of 160 Australians with Prader-Willi syndrome: trends in diagnosis, birth prevalence and birth characteristics. Am J Med Genet A 167A:371–378

Cassidy SB, Schwartz S, Miller JL, Driscoll DJ (2012) Prader-Willi syndrome. Genet Med 14:10–26

Faienza MF, Ventura A, Lauciello R et al (2012) Analysis of endothelial protein C receptor gene and metabolic profile in Prader-Willi syndrome and obese subjects. Obesity 20:1866–1870

Angulo MA, Butler MG, Cataletto ME (2015) Prader-Willi syndrome: a review of clinical, genetic, and endocrine findings. J Endocrinol Invest 38:1249–1263

Burnett LC, LeDuc CA, Sulsona CR et al (2016) Deficiency in prohormone convertase PC1 impairs prohormone processing in Prader-Willi syndrome. J Clin Invest. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI88648

Vestergaard P, Kristensen K, Bruun JM, Østergaard JR, Heickendorff L, Mosekilde L, Richelsen B (2004) Reduced bone mineral density and increased bone turnover in Prader-Willi syndrome compared with controls matched for sex and body mass index: a cross-sectional study. J Pediatr 144:614–619

Longhi S, Grugni G, Gatti D et al (2015) Adults with Prader-Willi syndrome have weaker bones: effect of treatment with GH and sex steroids. Calcif Tissue Int 96:160–166

Butler MG, Haber L, Mernaugh R, Carlson MG, Price R, Feurer ID (2001) Decreased bone mineral density in Prader-Willi syndrome: comparison with obese subjects. Am J Med Genet 103:216–222

Kroonen LT, Herman M, Pizzutillo PD, Macewen GD (2006) Prader-Willi syndrome: clinical concerns for the orthopaedic surgeon. J Pediatr Orthop 26:673–679

Sinnema M, Maaskant MA, van Schrojenstein Lantman-de Valk HM, van Nieuwpoort IC, Drent ML, Curfs LM, Schrander-Stumpel CT (2011) Physical health problems in adults with Prader-Willi syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 155A:2112–2124

Carrel AL, Myers SE, Whitman BY, Allen DB (2002) Benefits of long-term GH therapy in Prader-Willi syndrome: a 4-year study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:1581–1585

Carrel AL, Myers SE, Whitman BY, Eickhoff J, Allen DB (2010) Long-term growth hormone therapy changes the natural history of body composition and motor function in children with Prader-Willi syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:1131–1136

de Lind van Wijngaarden RF, Festen DA, Otten BJ et al (2009) Bone mineral density and effects of growth hormone treatment in prepubertal children with Prader-Willi syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:3763–3771

Jørgensen AP, Ueland T, Sode-Carlsen R et al (2013) Two years of growth hormone treatment in adults with Prader-Willi syndrome do not improve the low BMD. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98:E753–E760

Grugni G (2013) Prader-Willi syndrome: GH therapy and bone. Nat Rev Endocrinol 9:320–321

Khor EC, Fanshawe B, Qi Y et al (2016) Prader-Willi critical region, a non-translated, imprinted central regulator of bone mass: possible role in skeletal abnormalities in Prader-Willi syndrome. PLoS ONE 11:e0148155

Baron R, Kneissel M (2013) WNT signaling in bone homeostasis and disease: from human mutations to treatments. Nat Med 19:1791–1792

Qiang YW, Chen Y, Stephens O et al (2008) Myeloma-derived Dickkopf-1 disrupts Wnt-regulated osteoprotegerin and RANKL production by osteoblasts: a potential mechanism underlying osteolytic bone lesions in multiple myeloma. Blood 112:196–207

Lewiecki EM (2014) Role of sclerostin in bone and cartilage and its potential as a therapeutic target in bone diseases. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 6:48–57

Holm VA, Cassidy SB, Butler MG, Hanchett JM, Greenswag LR, Whitman BY, Greenberg F (1993) Prader-Willi syndrome: consensus diagnostic criteria. Pediatrics 91:398–402

Corneli G, Di Somma C, Baldelli R et al (2005) The cut-off limits of the GH response to GH-releasing hormone-arginine test related to body mass index. Eur J Endocrinol 153:257–264

Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH (2000) Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 320:1240–1243

Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM et al (2000) CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data 8:1–27

Tanner JM, Whitehouse RH (1976) Clinical longitudinal standards for height, weight, height velocity, weight velocity, and stages of puberty. Arch Dis Child 51:170–179

Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC (1985) Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28:412–419

Vignali DA (2000) Multiplexed particle-based flow cytometric assays. J Immunol Methods 243:243–255

Salle BL, Braillon P, Glorieux FH, Brunet J, Cavero E, Meunier PJ (1992) Lumbar bone mineral content measured by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry in newborns and infants. Acta Paediatr 81:953–958

Southard RN, Morris JD, Mahan JD, Hayes JR, Torch MA, Sommer A, Zipf WB (1991) Bone mass in healthy children: measurement with quantitative DXA. Radiology 179:735–738

Glastre C, Braillon P, David L, Cochat P, Meunier PJ, Delmas PD (1990) Measurement of bone mineral content of the lumbar spine by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry in normal children: correlations with growth parameters. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 70:1330–1333

Faienza MF, Brunetti G, Colucci S et al (2009) Osteoclastogenesis in children with 21-hydroxylase deficiency on long-term glucocorticoid therapy: the role of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand/osteoprotegerin imbalance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:2269–2276

Faienza MF, Brunetti G, Ventura A et al (2015) Mechanisms of enhanced osteoclastogenesis in girls and young women with Turner’s Syndrome. Bone 81:228–236

Brunetti G, Papadia F, Tummolo A et al (2016) Impaired bone remodeling in children with osteogenesis imperfecta treated and untreated with bisphosphonates: the role of DKK1, RANKL, and TNF-α. Osteoporos Int 27:2355–2365

Faienza MF, Ventura A, Delvecchio M et al (2017) High sclerostin and Dickkopf-1 (DKK-1) serum levels in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 102:1174–1181

Giordano P, Brunetti G, Lassandro G et al (2016) High serum sclerostin levels in children with haemophilia A. Br J Haematol 172:293–295

Delgado-Calle J, Bellido T (2015) Osteocytes and skeletal pathophysiology. Curr Mol Biol Rep 1(4):157–167

Mogul HR, Lee PD, Whitman BY et al (2008) Growth hormone treatment of adults with Prader-Willi syndrome and growth hormone deficiency improves lean body mass, fractional body fat, and serum triiodothyronine without glucose impairment: results from the United States multicenter trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:1238–1245

Sode-Carlsen R, Farholt S, Rabben KF et al (2012) Growth hormone treatment in adults with Prader-Willi syndrome: the Scandinavian study. Endocrine 41:191–199

Sanchez-Ortiga R, Klibanski A, Tritos NA (2012) Effects of recombinant human growth hormone therapy in adults with Prader-Willi syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Endocrinol 77:86–93

Tritos NA, Klibanski A (2016) Effects of growth hormone on bone. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 138:193–211

Bakker NE, Kuppens RJ, Siemensma EP et al (2015) Bone mineral density in children and adolescents with Prader-Willi syndrome: longitudinal study during puberty and 9 years of growth hormone treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 100:1609–1618

Nakamura Y, Murakami N, Iida T, Asano S, Ozeki S, Nagai T (2014) Growth hormone treatment for osteoporosis in patients with scoliosis of Prader-Willi syndrome. J Orthop Sci 19:877–882

Canalis E (2018) Management of endocrine disease: novel anabolic treatments for osteoporosis. Eur J Endocrinol 178(2):R33–R44

Doyon A, Fischer DC, Bayazit AK et al (2015) Markers of bone metabolism are affected by renal function and growth hormone therapy in children with chronic kidney disease. PLoS ONE 10:e0113482

Ueland T (2005) GH/IGF-I and bone resorption in vivo and in vitro. Eur J Endocrinol 152:327–332

Faienza MF, Chiarito M, D’amato G, Colaianni G, Colucci S, Grano M, Brunetti G. Monoclonal antibodies for treating osteoporosis. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2017:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/14712598.2018.1401607

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

G. Brunetti, G. Grugni, L. Piacente, M. Delvecchio, A. Ventura, P. Giordano, M. Grano, G. D’Amato, D. Laforgia, A. Crinò, and M. F. Faienza declare that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Human and Animal Rights

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all the legal guardians, and from the patients when applicable, prior to inclusion. All procedures were approved by local institutional review boards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brunetti, G., Grugni, G., Piacente, L. et al. Analysis of Circulating Mediators of Bone Remodeling in Prader–Willi Syndrome. Calcif Tissue Int 102, 635–643 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-017-0376-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-017-0376-y