Abstract

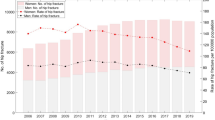

The aim of the study was to determine the number of hip fractures within defined countries for 2010 and the proportion attributable to osteoporosis. The number of incident hip fractures in one year in countries for which data were available was calculated from the population demography in 2010 and the age- and sex-specific risk of hip fracture. The number of hip fractures attributed to osteoporosis was computed as the number of hip fractures that would be saved assuming that no individual could have a femoral neck T-score of less than −2.5 SD (i.e., the lowest attainable T-score was that at the threshold of osteoporosis (=−2.5 SD). The total number of new hip fractures for 58 countries was 2.32 million (741,005 in men and 1,578,809 in women) with a female-to-male ratio of 2.13. Of these 1,159,727 (50 %) would be saved if bone mineral density in individuals with osteoporosis were set at a T-score of −2.5 SD. The majority (83 %) of these “prevented” hip fractures were found in men and women at the age of 70 years or more. The 58 countries assessed accounted for 83.5 % of the world population aged 50 years or more. Extrapolation to the world population using age- and sex-specific rates gave an estimated number of hip fractures of approximately 2.7 million in 2010, of which 1,364,717 were preventable with the avoidance of osteoporosis (264,162 in men and 1,100,555 in women). We conclude that osteoporosis accounts for approximately half of all hip fractures. Strategies to prevent osteoporosis could save up to 50 % of all hip fractures.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kanis JA; World Health Organization Scientific Group (2008) Assessment of osteoporosis at the primary health-care level. Technical Report. WHO Collaborating Centre, University of Sheffield, UK

Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Oden A, Melton LJ, Khaltaev N (2008) A reference standard for the description of osteoporosis. Bone 42:467–475

Kanis JA, Black D, Cooper C, Dargent P, Dawson-Hughes B, De Laet C, Delmas P, Eisman J, Johnell O, Jonsson B, Melton L, Oden A, Papapoulos S, Pols H, Rizzoli R, Silman A, Tenenhouse A, International Osteoporosis Foundation; National Osteoporosis Foundation (2002) A new approach to the development of assessment guidelines for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 13:527–536

Looker AC, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, Calvo MS, Harris TB, Heyse SP (1998) Updated data on proximal femur bone mineral levels of US adults. Osteoporos Int 8:468–486

Bacon WE, Maggi S, Looker A, Harris T, Nair CR, Giaconi J, Honkanen R, Ho SC, Peffers KA, Torring O, Gass R, Gonzalez N (1996) International comparison of hip fracture rates in 1988–89. Osteoporos Int 6:69–75

Cheng SY, Levy AR, Lefaivre KA, Guy P, Kuramoto L, Sobolev B (2011) Geographic trends in incidence of hip fractures: a comprehensive literature review. Osteoporos Int 22:2575–2586

Cooper C, Campion G, Melton LJ 3rd (1992) Hip fractures in the elderly: a world-wide projection. Osteoporos Int 2:285–289

Elffors L, Allander E, Kanis JA, Gullberg B, Johnell O, Dequeker J, Dilsen G, Gennari C, Lopes Vaz AA, Lyritis G, Mazzuoli GF, Miravet L, Passeri M, Perez Cano R, Rapado A, Ribot C (1994) The variable incidence of hip fracture in southern Europe: the MEDOS Study. Osteoporos Int 4:253–263

Gullberg B, Johnell O, Kanis JA (1997) World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 7:407–413

Haentjens P, Magaziner J, Colón-Emeric CS, Vanderschueren D, Milisen K, Velkeniers B, Boonen S (2010) Meta-analysis: excess mortality after hip fracture among older women and men. Ann Intern Med 152:80–90

Johnell O, Gullberg B, Allander E, Kanis JA (1992) The apparent incidence of hip fracture in Europe: a study of national register sources. MEDOS Study Group. Osteoporos Int 2:298–302

Johnell O, Kanis JA (2004) An estimate of the world-wide prevalence, disability and mortality associated with hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 15:897–902

Johnell O, Kanis JA (2006) An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 17:1726–1733

Kanis JA, Johnell O, De Laet C, Jonsson B, Oden A, Oglesby AK (2002) International variations in hip fracture probabilities: implications for risk assessment. J Bone Miner Res 17:1237–1244

Ström O, Borgström F, Kanis JA, Compston J, Cooper C, McCloskey EV, Jönsson B (2011) Osteoporosis: burden, health care provision and opportunities in the EU. A report prepared in collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA). Arch Osteoporos 6:59–155

Gauthier A, Kanis JA, Martin M, Compston J, Borgström F, Cooper C, McCloskey E, Committee of Scientific Advisors, International Osteoporosis Foundation (2011) Development and validation of a disease model for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 22:771–780

Gauthier A, Kanis JA, Jiang Y, Martin M, Compston JE, Borgström F, Cooper C, McCloskey EV (2011) Epidemiological burden of postmenopausal osteoporosis in the UK from 2010 to 2021: estimations from a disease model. Arch Osteoporos 6:179–188

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Dawson A, De Laet C, Jonsson B (2001) Ten year probabilities of osteoporotic fractures according to BMD and diagnostic thresholds. Osteoporos Int 12:989–995

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Jonsson B, De Laet C, Dawson A (2000) Risk of hip fracture according to World Health Organization criteria for osteoporosis and osteopenia. Bone 27:585–590

De Laet C, Oden A, Johnell O, Jonsson B, Kanis JA (2005) The impact of the use of multiple risk indicators for fracture on case finding strategies: a mathematical approach. Osteoporos Int 16:313–318

Johnell O, Kanis JA, Oden A, Johansson H, De Laet C, Delmas P, Eisman JA, Fujiwara S, Kroger H, Mellstrom D, Meunier PJ, Melton LJ 3rd, O’Neill T, Pols H, Reeve J, Silman A, Tenenhouse A (2005) Predictive value of bone mineral density for hip and other fractures. J Bone Miner Res 20:1185–1194

Kaptoge S, Reid DM, Scheidt-Nave C, Poor G, Pols HA, Khaw KT, Felsenberg D, Benevolenskaya LI, Diaz MN, Stepan JJ, Eastell R, Boonen S, Cannata JB, Glueer CC, Crabtree NJ, Kaufman JM, Reeve J (2007) Geographic and other determinants of BMD change in European men and women at the hip and spine. a population-based study from the Network in Europe for Male Osteoporosis (NEMO). Bone 40:662–673

Lunt M, Felsenberg D, Adams J, Benevolenskaya L, Cannata J, Dequeker J, Dodenhof C, Falch JA, Johnell O, Khaw KT, Masaryk P, Pols H, Poor G, Reid D, Scheidt-Nave C, Weber K, Silman AJ, Reeve J (1997) Population-based geographic variations in DXA bone density in Europe: the EVOS study. Eur Vertebral Osteoporos Osteoporos Int 7:175–189

Paggiosi MA, Glueer CC, Roux C, Reid DM, Felsenberg D, Barkmann R, Eastell R (2011) International variation in proximal femur bone mineral density. Osteoporos Int 22:721–729

Parr RM, Dey A, McCloskey EV, Aras N, Balogh A, Borelli A, Krishnan S, Lobo G, Qin LL, Zhang Y, Cvijetic S, Zaichick V, Lim-Abraham M, Bose K, Wynchank S, Iyengar GV (2002) Contribution of calcium and other dietary components to global variations in bone mineral density in young adults. Food Nutr Bull 23(3 suppl):180–184

Kanis JA, Odén A, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Wahl D, Cyrus Cooper C, IOF Working Group on Epidemiology and Quality of Life (2012) A systematic review of hip fracture incidence and probability of fracture worldwide. Osteoporos Int 23:2239–2256

United Nations (2010) World population prospects, the 2010 revision. UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/unpp/panel_indicators.htm. Accessed November 2, 2011

Cooper C, Cole ZA, Holroyd CR, Earl SC, Harvey NC, Dennison EM, Melton LJ, Cummings SR, Kanis JA, IOF CSA Working Group on Fracture Epidemiology (2011) Secular trends in the incidence of hip and other osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 22:1277–1288

Baddoura R, Hoteit M, El-Hajj Fuleihan G (2011) Osteoporotic fractures, DXA, and fracture risk assessment: meeting future challenges in the eastern Mediterranean region. J Clin Densitom 14:384–394

Karlsson MK, Gärdsell P, Johnell O, Nilsson BE, Akesson K, Obrant KJ (1993) Bone mineral normative data in Malmö, Sweden. Comparison with reference data and hip fracture incidence in other ethnic groups. Acta Orthop Scand 64:168–172

Löfman O, Larsson L, Ross I, Toss G, Berglund K (1997) Bone mineral density in normal Swedish women. Bone 20:167–174

Tuzun S, Akarirmak U, Uludag M, Tuzun F, Kullenberg R (2007) Is BMD sufficient to explain different fracture rates in Sweden and Turkey? J Clin Densitom 10:285–288

Tuzun S, Eskiyurt N, Akarirmak U, Saridogan M, Senocak M, Johansson H, Kanis JA, Turkish Osteoporosis Society (2012) Incidence of hip fracture and prevalence of osteoporosis in Turkey: the FRACTURK study. Osteoporos Int 23:949–955

Pedrazzoni M, Girasole G, Bertoldo F, Bianchi G, Cepollaro C, Del Puente A, Giannini S, Gonnelli S, Maggio D, Marcocci C, Minisola S, Palummeri E, Rossini M, Sartori L, Sinigaglia L (2003) Definition of a population-specific DXA reference standard in Italian women: the Densitometric Italian Normative Study (DINS). Osteoporos Int 14:978–982

Marwaha RK, Tandon N, Kaur P, Sastry A, Bhadra K, Narang A, Arora S, Mani K (2012) Establishment of age-specific bone mineral density reference range for Indian females using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. J Clin Densitom 15:241–249

Noon E, Singh S, Cuzick J, Spector TD, Williams FM, Frost ML, Howell A, Harvie M, Eastell R, Coleman RE, Fogelman I, Blake GM, IBIS-II Bone Substudy (2010) Significant differences in UK and US female bone density reference ranges. Osteoporos Int 21:1871–1880

Holt G, Khaw KT, Reid DM, Compston JE, Bhalla A, Woolf AD, Crabtree NJ, Dalzell N, Wardley-Smith B, Lunt M, Reeve J (2002) Prevalence of osteoporotic bone mineral density at the hip in Britain differs substantially from the US over 50 years of age: implications for clinical densitometry. Br J Radiol 75:736–742

Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, Jonsson B, de Laet C, Dawson A (2001) The burden of osteoporotic fractures: a method for setting intervention thresholds. Osteoporos Int 12:417–427

Kanis JA, Hans D, Cooper C, Baim S, Bilezikian JP, Binkley N, Cauley JA, Compston JE, Dawson-Hughes B, El-Hajj Fuleihan G, Johansson H, Leslie WD, Lewiecki EM, Luckey M, Oden A, Papapoulos SE, Poiana C, Rizzoli R, Wahl DA, McCloskey EV, Task Force of the FRAX Initiative (2011) Interpretation and use of FRAX in clinical practice. Osteoporos Int 22:395–411

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The authors have stated that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Appendix

The Hazard Function of Fracture According to BMD at the Femoral Neck

We assume that BMD has a distribution, which is very close to normal. Let h denote the hazard function of hip fracture of a randomly chosen individual from the population at a certain age and sex, and let σ be the standard deviation of the random variable BMD. The GR describes the increase in hip fracture risk for each SD decrease in femoral neck BMD. Then, if BMD is also specified and equal to z, the hazard function is

where the denominator E[exp ((−log (GR)/σ)·BMD)] is the expected value of exp((−log (GR)/σ)·BMD). The denominator is needed to make the expected value of equation (1) (the mean risk) equal to h. We can derive from equation (1) the hazard ratio when comparing the BMD value z − σ and z, which differ exactly 1 SD, is exp (log (GR)) = GR. Now we have to determine E[exp ((−log (GR)/σ)·BMD)]. For a random variable Y, which has a normal distribution with mean m and standard deviation SD, the following relationship is true:

In order to realize that E[exp (Y)] exp (m), we can apply Jensen’s inequality, which states that E[g(V)] > g(E[V]) for any random variable V when g is a convex function.

By applying relationship (2), we find

Thus,

and expression (1) equals

If the linear transformation t(z) = (z − E[BMD])/σ of z is used, then equation (1) can be written as:

If all individuals below a limit g of BMD would be carried to the BMD value equal to g and the other individuals are unchanged, then how would the risk change? First we can note that t(g) = (g − E[BMD])/σ. The calculated risk is

The second term equals

That implies that the risk (the hazard function) is

where Φ is the standardized normal distribution function.

The factor with which h is multiplied in equation (3) was calculated for the different gradients given in Johnell et al. [21] and the limit g = 0.558 g/cm2.

We note that

The mean value E[BMD] and the standard deviation σ vary by age and sex. The limit 0.558 fulfils Φ(t(0.558)) = 0.0062, when the mean and standard deviation equals that of women in the age interval 20–29 years. The limit corresponds to 2.5 SD below the mean of women 20–29 years of age.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Odén, A., McCloskey, E.V., Johansson, H. et al. Assessing the Impact of Osteoporosis on the Burden of Hip Fractures. Calcif Tissue Int 92, 42–49 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-012-9666-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-012-9666-6