Abstract

The temporal coordination of interpersonal behavior is a foundation for effective joint action with synchronized movement moderating core components of person perception and social exchange. Questions remain, however, regarding the precise conditions under which interpersonal synchrony emerges. In particular, with whom do people reliably synchronize their movements? The current investigation explored the effects of arbitrary group membership (i.e., minimal groups) on the emergence of interpersonal coordination. Participants performed a repetitive rhythmic action together with a member of the same or a different minimal group. Of interest was the extent to which participants spontaneously synchronized their movements with those of the target. Results revealed that stable coordination (i.e., in-phase synchrony) was most pronounced when participants interacted with a member of a different minimal group. These findings are discussed with respect to the functional role of interpersonal synchrony and the potential avenues by which the dynamics of rhythmic coordination may be influenced by group status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In-phase synchrony occurs when the movements of each individual are simultaneously at equivalent points of the movement cycle, while anti-phase synchrony occurs when such movements are simultaneously at opposite points of the movement cycle. Although the actions of interacting individuals will routinely move through the range of intermediate relative phase relationships (i.e., between 0° and 180°) they tend to settle at one of the two stable (i.e., attractor) states over time (see Schmidt and Richardson 2008).

Pilot testing revealed that participants were best able to maintain this frequency without the aid of a metronome.

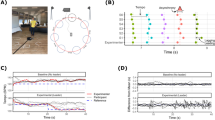

Analyses were conducted comparing the relative phase relationship between single arms (participant left with confederate right and vice versa). Identical patterns of results were found to those reported below. Furthermore, comparisons of intrapersonal coordination (i.e., participant’s left and right arms) revealed no significant differences from 0° (i.e., in-phase) as a function of condition, group or stage, nor any differences between these factors. Hence, for simplicity, only the results from analysis of averaged data are presented.

The same analyses were conducted using cross-spectral coherence as an alternative index of coordination. An identical pattern of results was obtained whereby participants in the minimal group condition who were in a different group to the confederate showed significantly more coherence (i.e., coordination) than those in the same group or participants in the control condition.

The same results were found for the control condition participants: expected interaction quality [M same = 5.4, M different = 5.9, t(14) = −0.91, p = .19]; self-reported liking for the confederate [Control: M same = 5.4, M different = 5.6, t(14) = −0.25, p = .40]. Equivalent 2(condition: minimal group or control) x 2(group: same or different) ANOVAs also revealed no significant effects.

References

Baumeister RF, Leary MR (1995) The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull 117:497–529

Berneiri FJ, Davis JM, Rosenthal R, Knee CR (1994) Interactional synchrony and rapport: measuring synchrony in displays devoid of sound and facial affect. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 20:303–311

Bernieri FJ (1988) Coordinated movement and rapport in teacher-student interactions. J Nonverbal Behav 12:120–138

Bourgeois P, Hess U (2008) The impact of social context on mimicry. Biol Psychol 77:343–352

Brewer MB (2007) The psychology of intergroup relations: social categorization, ingroup bias, and outgroup prejudice. In: Kruglanksi AW, Higgins ET (eds) Social psychology: handbook of basic principles, 2nd edn. Guilford, New York, pp 695–715

Cappella JN (1997) Behavioral and judged coordination in adult informal social interactions: vocal and kinesic indicators. J Pers Soc Psychol 72:119–131

Diehl M (1990) The minimal group paradigm: theoretical explanations and empirical findings. In: Stroebe W, Hewstone M (eds) European review of social psychology, vol 1. Wiley, London, pp 263–292

Haken H, Kelso JAS, Bunz H (1985) A theoretical model of phase transitions in human hand movements. Biol Cybern 51:347–356

Hove MJ, Risen JL (2009) It’s all in the timing: interpersonal synchrony increases affiliation. Soc Cognition 27:949–960

Iacoboni M (2009) Imitation, empathy, and mirror neurons. Annu Rev Psychol 60:653–670

Isabella RA, Belsky J, van Eye A (1989) Origins of mother–infant attachment: an examination of interactional synchrony during the infant’s first year. Dev Psychol 25:12–21

Julien D, Brault M, Chartrand É, Bégin J (2000) Immediacy behaviors and synchrony in satisfied and dissatisfied couples. Can J Behav Sci 32:84–90

Kirschner S, Tomasello M (2010) Joint music making promotes prosocial behaviour in 4-year-old children. Evol Hum Behav 31:354–364

Kugler PN, Turvey MT (1987) Information, natural law, and the self-assembly of rhythmic movement. Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ

LaFrance M (1979) Nonverbal synchrony and rapport: analysis by the cross-lag panel technique. Soc Psychol Quart 42:66–70

LaFrance M, Broadbent M (1976) Group rapport: posture sharing as a nonverbal indicator. Group Organ Stud 1:328–333

Lakens D (2010) Movement synchrony and perceived entitativity. J Exp Soc Psychol 46:701–708

Lakens D, Stel M (2011) If they move in sync, they must feel in sync: movement synchrony leads to attributed feelings of rapport. Soc Cognition 29:1–14

Lakin JL, Chartrand TL, Arkin RM (2008) I too am just like you: nonconscious mimicry as an automatic behavioral response to social exclusion. Psychol Sci 19:816–822

Lopresti-Goodman SM, Richardson MJ, Silva PL, Schmidt RC (2008) Period basin of entrainment for unintentional visual coordination. J Motor Behav 40:3–10

Macrae CN, Bodenhausen GV (2000) Social cognition: thinking categorically about others. Annu Rev Psychol 51:93–120

Macrae CN, Duffy OK, Miles LK, Lawrence J (2008) A case of hand waving: action synchrony and person perception. Cognition 109:152–156

Marsh KL, Richardson MJ, Schmidt RC (2009) Social connection through joint action and interpersonal coordination. Top Cogn Sci 1:320–339

Miles LK, Nind LK, Macrae CN (2009) The rhythm of rapport: interpersonal synchrony and social perception. J Exp Soc Psychol 45:585–589

Miles LK, Griffiths J, Richardson MJ, Macrae CN (2010a) Too late to coordinate: contextual influences on behavioral synchrony. Eur J Soc Psychol 40:52–60

Miles LK, Nind LK, Henderson Z, Macrae CN (2010b) Moving memories: behavioral synchrony and memory for self and others. J Exp Soc Psychol 46:457–460

Mummendey A, Simon B, Dietze C, Grünert M, Haeger G, Kessler S et al (1992) Categorization is not enough: intergroup discrimination in negative outcome allocation. J Exp Soc Psychol 28:125–144

Paladino MP, Mazzurega M, Pavani F, Schubert TW (2010) Synchronous multisensory stimulation blurs self-other boundaries. Psychol Sci 21:1202–1207

Park B, Judd CM (2005) Rethinking the link between categorization and prejudice within the social cognition perspective. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 9:108–130

Richardson MJ, Marsh KL, Isenhower RW, Goodman JRL, Schmidt RC (2007) Rocking together: dynamics of intentional and unintentional interpersonal coordination. Hum Movement Sci 26:867–891

Richeson JA, Trawalter S (2008) The threat of appearing prejudiced and race-based attentional biases. Psychol Sci 19:98–102

Rizzolatti G, Craighero L (2004) The mirror-neuron system. Annu Rev Neurosci 27:169–192

Schmidt RC, O’Brien B (1997) Evaluating the dynamics of unintended interpersonal coordination. Ecol Psychol 9:189–206

Schmidt RC, Richardson MJ (2008) Dynamics of interpersonal coordination. In: Fuchs A, Jirsa VK (eds) Coordination: neural, behavioral and social dynamics. Springer, Berlin, pp 281–307

Schmidt RC, Carello C, Turvey MT (1990) Phase transitions and critical fluctuations in visual coordination of rhythmic movements between people. J Exp Psychol Human 16:227–247

Schmidt RC, Christianson N, Carello C, Baron R (1994) Effects of social and physical variables on between-person visual coordination. Ecol Psychol 6:159–183

Sebanz N, Bekkering H, Knoblich G (2006) Joint action: bodies and minds moving together. Trends Cogn Sci 10:70–76

Semin GR (2007) Grounding communication: synchrony. In: Kruglanski A, Higgins ET (eds) Social psychology: handbook of basic principles, 2nd edn. Guilford, New York, pp 630–649

Semin GR, Cacioppo JT (2008) Grounding social cognition: synchronization, entrainment and coordination. In: Semin GR, Smith ER (eds) Embodied grounding: social, cognitive, affective, and neuroscientific approaches. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 119–147

Strogatz SH (2003) Sync: the emerging science of spontaneous order. Hyperion, New York

Tajfel H (1970) Experiments in intergroup discrimination. Sci Am 223:96–102

Tajfel H (1981) Human groups and social categories. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Tognoli E, Largarde J, DeGuzman GC, Kelso JAS (2007) The phi complex as a neuromarker of human social coordination. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 104:8190–8195

Valdesolo P, Ouyang J, DeSteno D (2010) The rhythm of joint action: synchrony promotes cooperative ability. J Exp Soc Psychol 46:693–695

van Ulzen NR, Lamoth CJC, Daffertshofer A, Semin GR, Beek PJ (2008) Characteristics of instructed and uninstructed interpersonal coordination while walking side-by-side. Neurosci Lett 432:88–93

Wilson M (2001) Perceiving imitatible stimuli: consequences of isomorphism between input and output. Psychol Bull 127:543–553

Wilson M, Knoblich G (2005) The case for motor involvement in perceiving conspecifics. Psychol Bull 131:460–473

Wiltermuth SS, Heath C (2009) Synchrony and cooperation. Psychol Sci 20:1–5

Yabar Y, Johnston L, Miles LK, Peace V (2006) Implicit behavioral mimicry: investigating the impact of group membership. J Nonverbal Behav 30:97–113

Acknowledgments

LKM was supported by a Research Councils of the UK Academic Fellowship, MJR was supported by the National Science Foundation (Grant #: BCS-0750190), and CNM was supported by a Royal Society-Wolfson Fellowship. Thanks to Natasha Flannigan and Brittany Christian for their assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miles, L.K., Lumsden, J., Richardson, M.J. et al. Do birds of a feather move together? Group membership and behavioral synchrony. Exp Brain Res 211, 495–503 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-011-2641-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-011-2641-z