Abstract

The long latency M2 electromyographic response of a suddenly stretched active muscle is stretch duration dependent of which the nature is unclear. We investigated the influence of the group II afferent blocker tizanidine on M2 response characteristics of the m. flexor carpi radialis (FCR). M2 response magnitude and eliciting probability in a group of subjects receiving 4 mg of tizanidine orally were found to be significantly depressed by tizanidine while tizanidine did not affect the significant linear relation of the M2 response to stretch duration. The effect of tizanidine on the M2 response of FCR is supportive of a group II afferent contribution to a compound response of which the stretch duration dependency originates from a different mechanism, e.g., rebound Ia firing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

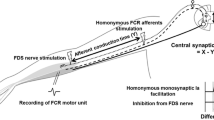

Electromyography after a sudden muscle stretch shows a velocity dependent, likely Ia afferent mediated short latency M1 (Nichols and Houk 1976; Houk et al. 1981; Hayashi et al. 1987; Cody et al. 1987; Thilmann et al. 1991; Grey et al. 2001) and a stretch velocity independent (Grey et al. 2001) long latency M2 reflex response which in the lower extremity is assumed to originate from muscle length coding group II afferents (Schieppati et al. 1995; Schieppati and Nardone 1997; Corna et al. 1995; Grey et al. 2001). In the upper extremity, the M2 response was found to be stretch duration dependent (Lee and Tatton 1982; Lewis et al. 2005) which does not necessarily involve length coding group II afferents. The origin of the M2 in the upper extremity is still controversial (Dietz 1992). It has been suggested that the M2 is mediated by Ia afferents (Lewis et al. 2005) or an Ia-transcortical pathway, as established in hand musculature (Matthews 1991; Palmer and Ashby 1992; Tsuji and Rothwell 2002) but questionable for more proximal muscles (Thilmann et al. 1991; Fellows et al. 1996). Other studies found the M2 response to be modulated by task instruction (Crago et al. 1976; Colebatch et al. 1979; Rothwell et al. 1980; Calancie and Bawa 1985) underpinning the transcortical pathway hypothesis, suggesting supraspinal modulation or a subcortical component of M2 (Lewis et al. 2006). Recently, it was even suggested that the long latency responses of the human arm involve internal models of limb dynamics (Kurtzer et al. 2008). Lourenco et al. (2006) identified four excitation peaks after nerve stimulation of the m flexor carpi radialis (FCR): two short latency group I excitations and two long latency peaks. A first, long latency high threshold peak was found to be depressed by tizanidine, an α2 adrenergic receptor agonist known from experiments in cat to selectively block the group II afferent input (Bras et al. 1989, 1990; Skoog 1996; Jankowska et al. 1998; Hammar and Jankowska 2003); a second low threshold peak was attributed to a transcortical pathway. Thus, it is strongly suggested that the M2 long latency response is a compound response.

However, aforementioned mechanisms do not explain the dependency of the M2 response on stretch duration. Lewis et al. (2005) proposed three mechanisms: (1) altered motoneuron firing properties following the M1 response, suggesting that the M2 response is an interrupted M1 response; (2) response characteristics of the muscle spindle receptors; (3) temporal summation along the reflex pathway, i.e., a threshold input duration is needed for a postsynaptic neuron to fire.

Schuurmans et al. (2009) elaborated on the first mechanism using a model approach and explained the stretch duration dependency of the M2 response from a synchronized M1 response or motoneuron firing and subsequent refractory period with ongoing Ia afferent activity, resulting in rebound Ia firing.

In the present paper, we further elaborate on the nature of the M2 response by studying the effect of tizanidine on the stretch duration dependency of the M2 response, within a repetitive measurement study design. We hypothesize that the M2 stretch duration dependency is not affected by tizanidine. In order to identify possible adaptation effects of repeated measurements, we used a control group. A frequent side effect of tizanidine is drowsiness which interferes with the measurements and could induce supraspinal confounding effects. Thus, a low, yet proven effective dose of 4 mg was applied (Emre et al. 1994).

Methods

Subjects

Ten healthy volunteers (mean age 47 ± 13 years, 9 male, 2 left handed) received 4 mg (≈50 μg/kg) tizanidine orally (T_1-group). Five subjects of this group (T_2-group) were re-measured on a different day without tizanidine (C_2-group). Nine subjects (mean age 43.8 ± 14, 7 male, 2 left handed) served as a control group (C_1-group). Permission was obtained from the local Medical Ethics Committee. All subjects gave informed consent prior to the measurements.

Measurement set-up

The methods, i.e., the measurement set-up and data processing are based on a previous study of our group (Schuurmans et al. 2009). Experiments were performed on the dominant hand. A wrist manipulator (Schouten et al. 2006) was used to evoke stretches of the m. flexor carpi radialis (FCR). The lower arm of the subject was fixed onto a table. The subject who was in sitting position, held the vertically placed handle of the manipulator (Fig. 1). The handle was attached via a lever arm to a servo-controlled motor. A force transducer mounted in the lever arm registered the wrist torques applied on the handle. The subject was asked to generate a 1 N m wrist flexion torque (target) in order to activate the FCR. Both target and actual torque (low pass filtered, second order Butterworth, 1 Hz) were displayed to assist the subjects. Filtering was applied to minimize rapid torque fluctuations due to the stretch perturbation in order to sustain the constant force task.

Muscle activity was recorded by bipolar EMG (Delsys Bagnoli system, electrode bar length 10 mm, bar distance 10 mm) on the middle of the belly of FCR and, to monitor possible co-contraction, the m. extensor carpi radialis (ECR).

Measurement protocol

Nine trials were performed every 20 min at eight subsequent occasions (T 1–T 8) after a baseline trial (T 0), 10 min before oral intake of tizanidine. Total measurement time was about 160 min. The trials consisted of series of ramp-and-hold stretches with a fixed velocity of 2 rad/s and stretch amplitudes of 0.06, 0.10, and 0.14 rad, resulting in stretch durations of 30, 50 and 70 ms, respectively. Ten repetitions for each of the three conditions were applied in a random order and separated by intervals of random duration between 3 and 4-s to avoid anticipation. Repetitions were clustered in four separate series to avoid fatigue. Directly after each trial, selective attention was assessed using a computer test. Before the experiment, the maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) in either flexion and extension direction was established.

Attention

Drowsiness is a known side effect of tizanidine. A computer keyboard key hit test on audio cues [test of sustained selective attention (TOSSA), Onderwater et al. 2004], was used to assess selective attention. Clusters of three repetitive short beeps (targets) were to be discerned from two- and four-beep clusters (distracters). In total 120 clusters were presented during 4 min. During the test the speed by which the clusters were presented was varied. The main outcome variable was the concentration strength, calculated from the percentage of correct hits diminished by the percentage of premature and false hits (100% implies an excellent concentration). The test was validated for healthy individuals (Onderwater et al. 2004).

Data processing and recording

The angle of the wrist (handle), the torque at the wrist (handle) and the EMG of the FCR and ECR were simultaneously recorded and digitized at 2.5 kHz. EMG was rectified and low pas filtered at 80 Hz (recursive third order Butterworth). Data were extracted from a time interval starting 400 ms before, till 1,000 ms after stretch onset. Segments in which the mean flexion torque prior to onset of the perturbation deviated more than ±0.1 N m from the instructed 1 N m were rejected. EMG activity was determined at three pre-defined time intervals: background activity (BG) at 400 ms until 20 ms before stretch onset; short latency M1 response at 20–50 ms after stretch onset; long latency M2 response at 55–100 ms after stretch onset. M1 and M2 response magnitudes were normalized to BG (reduced with BG and subsequently divided by BG) and averaged over the repetitions. The eliciting probability of both M1and M2 responses was calculated as the percentage of responses above BG. In order to group data at maximal effect of tizanidine, T min_T was defined in the T_1 and T_2 groups by identifying the trial number were the M2 response magnitude was minimal. Subsequently, M1 and M2 parameters in the T-group were calculated at T min_T. For the C_1 and C_2 groups, parameter values were calculated at mean T min_T. over all subjects in the T_1 group. All parameter values, i.e., M1 and M2 response magnitude and probability and concentration strength calculated at T min_T were compared to parameter values at baseline (T 0). Separate T min values were calculated for M2 response eliciting probability and concentration strength for comparison purposes.

Statistical testing

Statistical testing was performed using a linear mixed model (SPSS 16.0, α = 0.05) with time (T 0 vs. T min_T), stretch duration (30, 50 and 70 ms) and group as fixed factors. Two models were constructed, i.e., with and without group (T vs. C) as a repeated factor for T_2 and C_2 and T_1 and C_1 comparisons, respectively. A compound symmetry covariance model was used (Littell et al. 2000). Dependent variables were the magnitude and probability of the M1 response and the difference between either M1 and M2 response magnitude and M1 and M2 eliciting probability.

To assess the role of attention, the concentration strength at T 0 was compared to the concentration strength at T min_T using a linear mixed model with time and group (T_1 and C_1) as fixed factors.

Results

General

Figure 2 shows an example of the averaged responses over one trial in one subject prior to tizanidine intake. The three stretches with equal velocity (slope of the rising phase of the angle) but different amplitudes that were applied to the handle of the manipulator, resulted in three different stretch durations at the wrist, i.e., 30, 50 and 70 ms. The typical EMG response consisted of a short latency M1 response between 20 and 50 ms and a long latency M2 response between 55 and 100 ms after stretch onset, followed by a short depression. On average over all subjects, 14% of the segments were excluded for further analysis because the background torque prior to stretch varied more than 0.1 N m from the 1 N m target torque. During the torque task, the mean background activity (BG) of FCR was approximately 10% of MVC. The mean BG activity of ECR (antagonist) was lower than 2% of MVC in all subjects, indicating absence of co-contraction. No further analyses were performed for ECR.

Examples of the average EMG responses to the applied perturbations for one subject during one measurement session (10 min before intake). The different line types indicate the three different stretch durations. Upper panel angle of the handle, lower panel rectified and filtered EMG of the FCR, normalized to background level. The shaded boxes denote the defined M1 and M2 periods, respectively 20–50 and 55–100 ms after stretch onset (dashed line). 175×137 mm (600 × 600 DPI)

M1 response

As can be seen from Fig. 3a–d, both the M1 response magnitude and eliciting probability did not respond to stretch duration for all groups. No consistent differences between T 0 and T min_T were found for both response magnitude and probability. Results of the statistical procedure are outlined in Table 1.

M1 (a–d) and M2 (e–h) response magnitude (left panels) and eliciting probability (right panels) as a function of stretch duration (x axis). Results for the T_1 and C_1 group (a, b, e, f) and T_2–C_2 groups (c, d, g, h). Means and standard error of the mean are reported for T 0 (baseline measurement, lines) and T min_T (time of minimum value of M2 response magnitude in the T_1 group, dashed lines) for T (filled circle) and C (open circle) groups. 166 × 245 mm (600 × 600 DPI)

M2 response

The M2 response magnitude and probability related to stretch duration in a linear way, for all four groups (T_1, T_2, C_1, C_2, Table 1; Fig. 3e–h). A 50% drop in response magnitude between T 0 and T min_T was observed, both for the T_1 and T_2 group, while this was not the case in the C_1 and C_2 group. A different distribution of variances between T_1/C_1 and T_2/C_2 groups resulted in a different outcome of the statistical procedure, i.e., emphasis on time effect or time–group interaction. The same pattern, i.e., a reduction between T 0 and T min_T for the T but not for the C groups is observed for the M2 eliciting probability. Note that there is a difference in offset between T_1 and C_1 group regarding M2 response magnitude and eliciting probability, which is clearly visible in Fig. 3, however, not statistically significant (Table 1, group term). This offset is considerably smaller when T_2 and C_2 group are compared. T_2 and C_2 groups were the same subjects, measured at a different day.

The drop in M2 magnitude and eliciting probability in the T_1 and T_2 group did not affect the stretch amplitude relation as can be viewed from Fig. 3 and from the interaction term group-stretch duration which did not reach statistical significance (Table 1).

For the T_1 group, mean T min values of M2 response magnitude and probability were found at trial 6.1 and 6.2 corresponding to a time lag after tizanidine intake of 112 and 114 min, respectively.

Attention

There was a drop in concentration strength between T 0 and T min_T for both T- and C-group; the drop in the T-group was substantially larger. This drop was statistically significant while the group effect was not significant (Table 2). Mean T min values for the concentration strength were identified at trial 6.1, which corresponds to a lag time of 112 min after tizanidine intake.

Discussion

A depression of the stretch induced M2 response of the m. flexor carpi radialis (FCR) was found in a group of subjects receiving 4 mg of tizanidine orally, confirmative of a group II afferent contribution. However, the stretch duration dependency of M2 remained intact during tizanidine intake indicating that this is not a group II afferent effect but mediated by a different mechanism.

M1 response

The M1 response was not affected by stretch duration, tizanidine and repetition of measurements. In the present study, the stretch velocity was kept constant, whereas in a previous experiment the M1 response was found to be stretch velocity dependent (Schuurmans et al. 2009). This is consistent with a stretch velocity dependent, monosynaptic Ia afferent origin (Houk et al. 1981).

M2 response: general effect of tizanidine

The current experiment indicates a distinct effect of tizanidine on the M2 response. Tizanidine is a known group II blocker in cats (Bras et al. 1990; Skoog 1996) and has no influence on Ia afferents (Hammar and Jankowska 2003). Thus, a group II afferent contribution to M2 is plausible.

Tizanidine has a known effect on spasticity (Emre et al. 1994). A prominent role of group II (hyper) activity in spasticity is assumed, resulting from lack of inhibitory control of interneurons in excitatory pathways between group II muscle afferents and motoneurons by descending monoaminergic pathways (Jankowska et al. 1994; Hammar and Jankowska 2003).

Explaining the M2 from at least partial group II afferent activity is confirmed by the antispastic effect of l-dopa, another known group II afferent blocker (Eriksson et al. 1996).

M2 response: stretch duration

The observed stretch duration dependence of the M2 response of FCR is well known under task conditions similar to the tasks applied in this study (“do not intervene”, “let go” or “keep a certain force”). Lee and Tatton (1982) and Lewis et al. (2005) found the M2 response or probability to stretch duration relationship to be nonlinear, with a critical stretch duration below which no response could be elicited, a steep rising phase and a plateau phase. Critical stretch duration for the wrist was found to be 43.8 ms (Lee and Tatton 1982). In the present study, stretch durations of 30, 50 and 70 ms were applied ranging from critical duration to plateau phase. The M2 response probability in T- and C-group was about 60% for the 30 ms sub-threshold stretches and approached the 100% for the 70 ms plateau stretches. The difference in critical stretch duration between Lee and Tatton and present study may be caused by the different joint torques used in the experiments. Lee and Tatton used 0.5 N m, this study 1 N m. Muscle spindle sensitivity increases with torque, and M1 and M2 responses are known to scale with contraction level (Calancie and Bawa 1985; Toft et al. 1989).

The stretch duration dependency was explained by Lee and Tatton from a convergent hypothesis, for which Lewis et al. found no supportive evidence using a double stimulus paradigm. Alternative hypotheses were suggested, i.e., Schuurmans et al. (2009) used a computational model to demonstrate that it is possible to explain the stretch dependency by: (1) synchronization of the motor neuron pool firing by a sudden stimulus; (2) subsequent synchronized refractory period for all motor neurons; (3) sustained Ia afferent firing while the stretch continues, resulting in a second synchronized response within the M2 latency time window.

Alternatively, M2 stretch duration dependency can also be explained by group II afferent firing characteristics. Our results demonstrate a partial depression of M2 by tizanidine while the stretch duration dependency is not significantly affected: this relation remains linear with a constant slope. It is likely that tizanidine also affects the stretch duration sensitivity of group II afferents, resulting in a lower slope angle of the stretch duration dependency relation. In the case that tizanidine would block group II afferents, without affecting the stretch duration sensitivity, a proportional blocking of group II afferent activity would negatively affect the slope of the linear stretch duration dependency as well. Thus, the fact that M2 amplitude is depressed while the stretch duration dependency remains intact, allows for but a few conclusions. We state that the long latency reflex stretch dependency is likely caused by a different mechanism than group II activity, possibly Ia rebound firing.

In line with Lourenco et al. (2006) using neural stimulation, the present study confirmed the compound origin of the M2 response, at least consisting of a group II afferent and a stretch duration dependent contribution, which we state is a result of rebound Ia firing.

Attention

The sedative effect of tizanidine is well known (Wagstaff and Bryson 1997; Miettinen et al. 1996). We applied about a threefold reduced dose of tizanidine than is commonly applied in stretch reflex experiments, i.e., 4 versus 12 mg, i.e., about 50 vs. 150 μg/kg, in order to ensure proper task performance and to minimize supraspinal effects. In a study of Maupas et al. (2004) using 150 μg/kg of tizanidine, all patients enrolled in the study were reported to fall asleep. Emre et al. (1994), found that pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of 4 and 8 mg doses were comparable, while an antispastic effect of a 2 mg dose could not be established. In that study, maximal plasma concentrations and antispastic effect were found around 90–100 min after intake, which is in line with the maximal effect on the M2 responses at about 112 min as found in the present study.

At T min_T, the concentration strength appeared to drop significantly, with a substantially larger drop in the T_1 group compared to the C_1 group, indicating central effects of tizanidine i.e. on attention. Central and peripheral effects of tizanidine may be separated by time lag differences between the maximal effects on M2 response magnitude and concentration strength. However, mean time lags T 0–T min for M2 response magnitude and concentration strength were similar, which is no surprise considering that the α2 adrenergic receptor agonists are known for their rapid penetration in the Central Nervous System (Miettinen et al. 1996). The fact that even low doses of tizanidine result in measurable central effects, implies that it is very difficult to separate peripheral from central effects in humans taking tizanidine orally. However, the relatively large drop of the M2 response compared to the drop in awareness is confirmative of a supposed selective II afferent spinal effect of tizanidine.

M2 response probability

Likewise to the response magnitude, the probability of eliciting a M2 response was stretch duration dependent and was significantly depressed by tizanidine, confirmative of our hypothesis. In the present study, both M2 response magnitude and eliciting probability were regarded as parameters describing the same M2 activity. The M2 response magnitude may be related to the number of firing motor neurons while the eliciting probability reflects a threshold mechanism. However, the present study does not allow for further discrimination in underlying mechanisms.

Note that while the M1 responses were comparable, the M2 response magnitude and the eliciting probability were higher in the T-group, with a more outspoken difference for the lowest stretch duration. This is most likely explained by an inter individual variability causing a difference between groups, i.e., T_1 and C_1 group. The difference between T_2 and C_2 groups, which were the same subjects, was much smaller. Additional variability may be introduced by variability in electrode placement and/or a higher level of arousal caused by anticipation effects in the drug taking group. The latter would imply a role of subcortical components (Lewis et al. 2006). However, there was no clear correlation with concentration strength. Aforementioned effects should be studied or controlled for in a placebo controlled study design. However, we do not believe that a possible effect interferes with our conclusions regarding the effect of tizanidine on the stretch duration dependency of the M2 response of FCR.

References

Bras H, Cavallari P, Jankowska E, McCrea D (1989) Comparison of effects of monoamines on transmission in spinal pathways from group I and II muscle afferents in the cat. Exp Brain Res 76:27–37

Bras H, Jankowska E, Noga B, Skoog B (1990) Comparison of effects of various types of NA and 5-HT agonists on transmission from group II muscle afferents in the cat. Eur J Neurosci 2:1029–1039

Calancie B, Bawa P (1985) Firing patterns of human flexor carpi radialis motor units during the stretch reflex. J Neurophysiol 53:1179–1193

Cody FWJ, Goodwin CN, Richardson HC (1987) Effects of ischaemia upon reflex electromyographic responses evoked by stretch and vibration in human wrist flexor muscles. J Physiol 391:589–609

Colebatch JG, Gandevia SC, McCloskey DI, Potter EK (1979) Subject instruction and long latency reflex responses to muscle stretch. J Physiol 292:527–534

Corna S, Grasso M, Nardone A, Schieppati M (1995) Selective depression of medium-latency leg and foot muscle responses to stretch by an alpha 2-agonist in humans. J Physiol 484:803–809

Crago PE, Houk JC, Hasan Z (1976) Regulatory actions of human stretch reflex. J Neurophysiol 39(5):925–935

Dietz V (1992) Human neuronal control of automatic functional movements: interaction between central programs and afferent input. Physiol Rev 72:33–69

Emre M, Leslie GC, Muir C, Part NJ, Pokorny R, Roberts RC (1994) Correlations between dose, plasma concentrations, and antispastic action of tizanidine (Sirdalud) J. Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 57:1355–1359

Eriksson J, Olausson B, Jankowska E (1996) Antispastic effects of L-dopa. Exp Brain Res 111:296–304

Fellows SJ, Topper R, Schwarz M, Thilmann AF, Noth J (1996) Stretch reflexes of the proximal arm in a patient with mirror movements: absence of bilateral long- latency components. Electroenceph Clin Neurophys 101:79–83

Grey MJ, Ladouceur M, Andersen JB, Nielsen JB, Sinkjaer T (2001) Group II muscle afferents probably contribute to the medium latency soleus stretch reflex during walking in humans. J Physiol 534:925–933

Hammar I, Jankowska E (2003) Modulatory effects of a1–a2 and b-receptor agonists on feline spinal interneurons with monosynaptic input from group I muscle afferents. J Physiol 23:332–338

Hayashi R, Becker WJ, White DG, Lee RG (1987) Effects of ischemic nerve block on the early and late components of the stretch reflex in the human forearm. Brain Res 17:341–344

Houk JC, Rymer WZ, Crago PE (1981) Dependence of dynamic response of spindle receptors on muscle length and velocity. J Neurophysiol 46:143–166

Jankowska E, Lackberg ZS, Dyrehag LE (1994) Effects of monoamines on transmission from group II muscle afferents in sacral segments in the cat. Eur J Neurosci 6:1058–1061

Jankowska E, Gladden MH, Czarkowska-Bauch J (1998) Modulation of responses of feline gamma-motoneurones by noradrenaline, tizanidine and clonidine. J Physiol 512:521–531

Kurtzer IL, Pruszynski JA, Scott SH (2008) Long-latency reflexes of the human arm reflect an internal model of limb dynamics. Curr Biol 18:449–453

Lee RG, Tatton WG (1982) Long latency reflexes to imposed displacements of the human wrist: dependence on duration of movement. Exp Brain Res 45:207–216

Lewis G, Perreault EJ, MacKinnon C (2005) The influence of perturbation duration and velocity on the long-latency response to stretch in the biceps muscle. Exp Brain Res 163:361–369

Lewis G, MacKinnon CD, Perreault EJ (2006) The effect of task instruction to the excitability of spinal and supraspinal reflex pathways projecting to the biceps muscle. Exp Brain Res 174:413–425

Littell RC, Pendergast J, Natarajan R (2000) Modelling covariance structure in the analysis of repeated measures data. Statist Med 19:1793–1819

Lourenco G, Iglesias C, Cavallari P, Pierrot-Deseilligny E, Marchand-Pauvert V (2006) Mediation of late excitation from human hand muscles via parallel group II spinal and group I transcortical pathways. J Physiol 572:585–603

Matthews PBC (1991) The human stretch reflex and the motor cortex. TINS 14:87–91

Maupas E, Marque P, Roques CF, Simonetta-Moreau M (2004) Modulation of the transmission in group II heteronymous pathways by tizanidine in spastic hemiplegic patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 75:130–135

Miettinen TJ, Kanto JH, Salonen MA, Scheinin M (1996) The sedative and sympatholytic effects of oral tizanidine in healthy volunteers. Anesth Analg 82:817–820

Nichols TR, Houk JC (1976) Improvement in linearity and regulation of stiffness that results from actions of stretch reflex. J Neurophysiol 39:119–142

Onderwater A, Kovacs F, Middelkoop HAM (2004) Validating a new attention test: the TOSSA; a pilot-study. Master Thesis, University of Leiden

Palmer E, Ashby P (1992) Evidence that a long latency stretch reflex in humans is transcortical. J Physiol 449:429–440

Rothwell JC, Traub MM, Marsden CD (1980) Influence of voluntary intent on the human long-latency stretch reflex. Nature 286:496–498

Schieppati M, Nardone A (1997) Medium latency stretch reflexes of foot and leg muscles analysed by cooling the lower limb in standing humans. J Physiol 503:691–698

Schieppati M, Nardone A, Siliotto R, Grasso M (1995) Early and late stretch responses of human foot muscles induced by perturbation of stance. Exp Brain Res 105:411–422

Schouten AC, De Vlugt E, Van Hilten JJ, Van der Helm FCT (2006) Design of a torque-controlled manipulator to analyze the admittance of the wrist joint. J Neurosci Meth 154:134–141

Schuurmans J, de Vlugt E, Schouten AC, Meskers CGM, De Groot JH, Van der Helm FCT (2009) The monosynaptic Ia afferent pathway can largely explain the stretch duration effect of the long latency M2 response. Exp Brain Res 193:491–500

Skoog B (1996) A comparison of the effects of two antispastic drugs, tizanidine and baclofen on synaptic transmission form muscle spindle afferents to spinal interneurons in cats. Acta Physiol Scand 156:81–90

Thilmann AF, Schwarz M, Töpper R, Fellows SJ, Noth J (1991) Different mechanisms underlie the long- latency stretch reflex response of active human muscle at different joints. J Physiol 444:631–643

Toft E, Sinkjaer T, Andreassen S (1989) Mechanical and electromyographic responses to stretch of the human anterior tibial muscle at different levels of contraction. Exp Brain Res 74(1):213–219

Tsuji T, Rothwell JC (2002) Long lasting effects of rTMS and associated peripheral sensory input on MEPs, SEPs and transcortical reflex excitability in humans. J Physiol 540:367–376

Wagstaff AJ, Bryson HM (1997) Tizanidine A review of its pharmacology, clinical efficacy and tolerability in the management of spasticity associated with cerebral and spinal disorders. Drugs 53:435–452

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Meskers, C.G.M., Schouten, A.C., Rich, M.M.L. et al. Tizanidine does not affect the linear relation of stretch duration to the long latency M2 response of m. flexor carpi radialis . Exp Brain Res 201, 681–688 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-009-2085-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-009-2085-x