Abstract

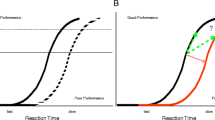

In five experiments we compared prosaccade and antisaccade performance in normal human observers. This was first examined for visual stimulation in temporal or nasal hemifields, under monocular viewing. Prosaccades were faster following temporal than nasal stimulation, in accordance with previous results. The novel finding was that the opposite pattern was observed for antisaccades, consistent with a difficulty in overcoming a stronger prosaccade tendency after temporal-hemifield stimulation. A second experiment showed that these results were not simply due to antisaccades following nasal stimulation benefitting from being made towards a temporal place-holder. Prosaccades and antisaccades were then compared for visual versus somatosensory stimulation. The substantial latency difference between prosaccades and antisaccades for visual stimuli was eliminated for somatosensory stimuli. Antisaccades can thus benefit in relative terms when the competing prosaccadic tendency is weakened; but two further experiments revealed that not all manipulations induce opposing outcomes for the two types of saccade. Although reducing the contrast of visual targets can slow prosaccades and conversely speed antisaccades, this was not the case at the lowest contrast level used, where both types of saccade were slowed, thus indicating some common limiting source. Moreover, warning sounds presented shortly before a visual target speeded both prosaccades and antisaccades. These results illustrate that several factors which slow prosaccades can speed antisaccades (consistent with competition between different pathways); but also reveal some notable exceptions, where both types of saccade are slowed or speeded together, suggesting some common pathways that may precede competition over the direction of the saccade.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We are grateful to an anonymous referee for raising this issue.

References

Amlot R, Walker R, Driver J, Spence C (2003) Multimodal visual-somatosensory integration in saccade generation. Neuropsychologia 41:1–15

Blanke O, Grüsser O (2001) Saccades guided by somatosensory stimuli. Vision Res 41:2407–2412

Bruce CJ, Goldberg ME (1985) Primate frontal eye fields. I. Single neurons discharging before saccades. J Neurophysiol 53:603–635

Chen LL, Wise SP (1995) Neuronal activity in the supplementary eye field during acquisition of conditional oculomotor associations. J Physiol 73:1101–1121

Cherkasova MV, Manoach DS, Intriligator JM, Barton JJ (2002) Antisaccades and task-switching: interactions in controlled processing. Exp Brain Res 144:528–537

Cornelissen FW, Kimmig H, Schira M, Rutschmann RM, Maguire RP, Broerse A, Den Boer JA, Greenlee MW (2002) Event-related fMRI responses in the human frontal eye fields in a randomized pro- and antisaccade task. Exp Brain Res 145:270–274

Craig GL, Stelmach LB, Tam WJ (1999) Control of reflexive and voluntary saccades in the gap effect. Percept Psychophys 61:935–942

Doma H, Hallett PE (1988a) Rod-cone dependence of saccadic eye-movement latency in a foveating task. Vision Res 28:899–913

Doma H, Hallett PE (1988b) Dependence of saccadic eye-movements on stimulus luminance, and an effect of task. Vision Res 28:915–924

Dorris MC, Pare M, Munoz DP (1997) Neuronal activity in monkey superior colliculus related to the initiation of saccadic eye movements. J Neurosci 17:8566–8579

Edelman JA, Keller EL (1996) Activity of visuomotor burst neurons in the superior colliculus accompanying express saccades. J Neurophysiol 76:908–926

Edelman JA, Keller EL (1998) Dependence on target configuration of express saccade-related activity in the primate superior colliculus. J Neurophysiol 80:1407–1426

Edelman JA, Intriligator J, Barton JJ (2000) Is poor antisaccade performance in human due to the absence of a visual target, or to reflex suppression? Soc Neurosci Abstr 25:362.3

Everling S, Fischer B (1998) The antisaccade: a review of basic research and clinical studies. Neuropsychologia 36:885–899

Everling S, Munoz DP (2000) Neuronal correlates for preparatory set associated with pro-saccades and anti-saccades in the primate frontal eye field. J Neurosci 20:387–400

Everling S, Krappmann P, Flohr H (1997) Cortical potentials preceding pro- and antisaccades in man. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 102:356–362

Everling S, Dorris MC, Munoz DP (1998) Reflex suppression in the antisaccade task is dependent on prestimulus neural processes. J Neurophysiol 80:1584–1589

Everling S, Dorris MC, Klein RM, Munoz DP (1999) Role of primate superior colliculus in preparation and execution of anti-saccades and pro-saccades. J Neurosci 19:2740–2754

Fan J, McCandliss BD, Sommer T, Raz A, Posner MI (2002) Testing the efficiency and independence of attentional networks. J Cogn Neurosci 14:340–347

Fischer B, Boch R (1983) Saccadic eye movements after extremely short reaction times in the monkey. Brain Res 754:285–297

Fischer B, Breitmeyer B (1987) Mechanisms of visual attention revealed by saccadic eye movements. Neuropsychologia 25:73–83

Fischer B, Weber H (1992) Characteristics of “anti” saccades in man. Exp Brain Res 89:415–424

Fischer B, Weber H (1993) Express saccades and visual attention. Behav Brain Sci 16:553–567

Forbes K, Klein RM (1996) The magnitude of the fixation offset effect with endogenously and exogenously controlled saccades. J Cogn Neurosci 8:344–352

Funahashi S, Chafee MV, Goldman-Rakic PS (1993) Prefrontal neuronal activity in rhesus monkeys performing a delayed antisaccade task. Nature 365:753–756

Goldberg ME (2000) The control of gaze. In: Kandel E, Schwartz JH, Jessel TM (eds) Principles of neural science, 4th edn. McGraw-Hill, New York, pp 782–800

Gottlieb J, Goldberg ME (1999) Activity of neurons in the lateral intraparietal area of the monkey during an antisaccade task. Nat Neurosci 2:906–912

Groh JM, Sparks DL (1996a) Saccades to somatosensory targets. I. Behavioral characteristics. J Neurophysiol 75:412–427

Groh JM, Sparks DL (1996b) Saccades to somatosensory targets. II. Motor convergence in primate superior colliculus. J Neurophysiol 75:428–438

Groh JM, Sparks DL (1996c) Saccades to somatosensory targets. III. Eye-position-dependent somatosensory activity in primate superior colliculus. J Neurophysiol 75:439–453

Grosbras MH, Leonards U, Lobel E, Poline JB, LeBihan D, Berthoz A (2001) Human cortical networks for new and familiar sequences of saccades. Cereb Cortex 11:936–945

Guitton D, Buchtel HA, Douglas RM (1985) Frontal lobe lesions in man cause difficulties in suppressing reflexive glances and in generating goal directed saccades. Exp Brain Res 58:455–472

Hallett PE (1978) Primary and secondary saccades to goals defined by instructions. Vision Res 18:1279–1296

Hallett PE, Adams BD (1980) The predictability of saccadic latency in a novel voluntary oculomotor task. Vision Res 20:329–339

Harrington LK, Peck CK (1998) Spatial disparity affects visual-auditory interactions in human sensorimotor processing. Exp Brain Res 122:247–252

Krappmann P, Everling S, Flohr H (1998) Accuracy of visually and memory-guided antisaccades in man. Vision Res 38:2979–2985

Kristjánsson Á, Chen Y, Nakayama K (2001) Less attention is more in the preparation of antisaccades, but not prosaccades. Nat Neurosci 4:1037–1042

Leigh RJ, Zee DS (1999) The neurology of eye movements, 3rd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Livingstone M, Hubel D (1988) Segregation of form, color, movement, and depth: anatomy, physiology, and perception. Science 240:740–749

Macaluso E, Driver J (2003) Multimodal spatial representations in human parietal cortex: evidence from functional imaging. In: Siegel AM, Andersen RA, Freund H, Spencer DD (eds) Advances in neurology: the parietal lobe. LWW, Philadelphia

Marrocco RT, Li RH (1977) Monkey superior colliculus: properties of single cells and their afferent inputs. J Neurophysiol 40:844–860

Munoz DP, Wurtz RH (1995a) Saccade-related activity in monkey superior colliculus. I. Characteristics of burst and build-up cells. J Neurophysiol 73:2313–2333

Munoz DP, Wurtz RH (1995b) Saccade-related activity in monkey superior colliculus. II. Spread of activity during saccades. J Neurophysiol 73:2334–2348

Neggers SWF, Bekkering H (1999) Integration of visual and somatosensory target information in goal-directed eye and arm movements. Exp Brain Res 125:97–107

Posner MI (1978) Chronometric explorations of mind. Erlbaum, Hillsdale

Posner MI, Cohen Y (1984) Attention and the control of movements. In: Stelmach GE, Requin J (eds) Tutorials in motor behaviour. North Holland, Amsterdam, pp 243–258

Posner MI, Petersen SE (1990) The attention system of the human brain. Annu Rev Neurosci 13:25–42

Rafal R (2002) Cortical control of visuomotor reflexes. In: Stuss DT, Knight RT (eds) Principles of frontal lobe function. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 149–158

Rafal R, Henik A, Smith J (1991) Extrageniculate contributions to reflex visual orienting in normal humans: a temporal hemifield advantage. J Cogn Neurosci 3:322–328

Rafal R, Machado L, Ro T, Ingle H (2000) Looking forward to looking: saccade preparation and control of the visual grasp reflex. In: Monsell S, Driver J (eds) Control of cognitive processes: attention and performance XX. MIT Press, Cambridge, USA, pp 155–174

Reingold EM, Stampe DM (2002) Saccadic inhibition in voluntary and reflexive saccades. J Cogn Neurosci 14:371–388

Reuter-Lorenz PA, Hughes HC, Fendrich R (1991) The reduction of saccadic latency by prior offset of the fixation point: an analysis of the gap effect. Percept Psychophys 49:167–175

Ross LE, Ross SM (1980) Saccade latency and warning signals: stimulus onset, offset, and change as warning events. Percept Psychophys 27:251–257

Ross SM, Ross LE (1981) Saccade latency and warning signals: effects of auditory and visual stimulus onset and offset. Percept Psychophys 29:429–437

Sapir A, Soroker N, Berger A, Henik A (1999) Inhibition of return in spatial attention: direct evidence for collicular generation. Nat Neurosci 2:1053–1054

Sapir A, Rafal R, Henik A (2002) Attending to the thalamus: inhibition of return and nasal-temporal asymmetry in the pulvinar. Neuroreport 13:693–697

Saslow MG (1967) Effects of components of displacement-step upon latency for saccadic eye movements. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis 57:1024–1029

Schall JD (1991) Neuronal activity related to visually guided saccadic eye movements in the supplementary motor area of rhesus monkeys. J Neurophysiol 66:530–558

Schall JD, Thompson KG (1999) Neural selection and control of visually guided eye movements. Annu Rev Neurosci 22:241–259

Schlag-Rey M, Amador N, Sanchez H, Schlag J (1997) Antisaccade performance predicted by neuronal activity in the supplementary eye field. Nature 390:398–401

Shulman GL (1984) An asymmetry in the control of eye movements and shifts of attention. Acta Psychol (Amst) 55:53–69

Sparks DL, Barton EJ (1993) Neural control of saccadic eye movements. Curr Opin Neurobiol 3:966–972

Sparks DL, Rohrer WH, Zhang Y (2000) The role of the superior colliculus in saccade initiation: a study of express saccades and the gap effect. Vision Res 40:2763–2777

Stein BE, Meredith MA (1993) The merging of the senses. MIT Press, Cambridge, USA

Sternberg S (1969) The discovery of processing stages: extensions of Donders’ method. In: Koster WG (ed) Attention and performance II. North Holland, Amsterdam, pp 276–315

Sumner P, Adamjee T, Mollon JD (2002) Signals invisible to the collicular and magnocellular pathways can capture visual attention. Curr Biol 12:1312–1316

Tassinari G, Campara D (1996) Consequences of covert orienting to non-informative stimuli of different modalities: a unitary mechanism? Neuropsychologia 34:235–245

Taylor TL, Klein RM, Munoz DP (1999) Saccadic performance as a function of the presence and disappearance of auditory and visual fixation stimuli. J Cogn Neurosci 11:206–213

Weber H (1995) Presaccadic processes in the generation of pro and antisaccades in human subjects—a reaction time study. Perception 24:1265–1280

Zambarbieri D, Beltrami G, Versino M (1995) Saccade latency toward auditory targets depends on the relative position of the sound source with respect to the eyes. Vision Res 35:3305–3312

Zhang M, Barash S (2000) Neuronal switching of sensorimotor transformations for antisaccades. Nature 408:971–975

Acknowledgements

A.K. was supported by a Long Term Fellowship from the Human Frontiers Science Program (Number LT00126/2002-C/2). J.D. was supported by programme grants from the Medical Research Council (UK) and the Wellcome Trust. Thanks are due to Francesco Pavani, Angelo Maravita, Chris Rorden and Steffan Kennett for technical help.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kristjánsson, Á., Vandenbroucke, M.W.G. & Driver, J. When pros become cons for anti- versus prosaccades: factors with opposite or common effects on different saccade types. Exp Brain Res 155, 231–244 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-003-1717-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-003-1717-9