Abstract

Motivated by the Strong Cosmic Censorship Conjecture for asymptotically Anti-de Sitter (AdS) spacetimes, we initiate the study of massive scalar waves satisfying \(\Box _g \psi - \mu \psi =0\) on the interior of AdS black holes. We prescribe initial data on a spacelike hypersurface of a Reissner–Nordström–AdS black hole and impose Dirichlet (reflecting) boundary conditions at infinity. It was known previously that such waves only decay at a sharp logarithmic rate (in contrast to a polynomial rate as in the asymptotically flat regime) in the black hole exterior. In view of this slow decay, the question of uniform boundedness in the black hole interior and continuity at the Cauchy horizon has remained up to now open. We answer this question in the affirmative.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

We initiate the study of (massive) linear waves satisfying

on the interior of asymptotically Anti-de Sitter (AdS) black holes \(({\mathcal {M}},g)\). In the context of asymptotically AdS spacetimes it is natural to consider (possibly negative) mass parameters \(\mu \) satisfying the Breitenlohner–Freedman [6] bound \(\mu > \frac{3}{4}\Lambda \), where \(\Lambda <0\) is the cosmological constant of the underlying spacetime. In particular, this covers the conformally invariant operator with \(\mu = \frac{2}{3}\Lambda \). We will consider Reissner–Nordström–AdS (RN–AdS) black holes [7] which can be viewed as the simplest model in the context of the question of stability of the Cauchy horizon. These spacetimes are spherically symmetric solutions of the Einstein equations

coupled to the Maxwell equations via the energy momentum tensor \(T_{\mu \nu }\). Our main result Theorem 1 (see Theorem 3.1 in Sect. 3 for its precise formulation) is the statement of uniform boundedness in the black hole interior and continuity at the Cauchy horizon of solutions to (1.1) arising from initial data on a spacelike hypersurface on RN–AdS. We moreover assume Dirichlet (reflecting) boundary conditions at infinity. Our result is surprising because in contrast to black hole backgrounds with non-negative cosmological constants (\(\Lambda \ge 0\)), the decay of \(\psi \) in the exterior region for asymptotically AdS black holes (\(\Lambda <0\)) is only logarithmic as shown by Holzegel–Smulevici [40] (cf. polynomial [1, 19, 59] (\(\Lambda =0\)) and exponential [5, 25] (\(\Lambda >0\))). Indeed, the logarithmic decay is too slow to adapt the mechanism exploited in previous studies of black hole interiors [14, 17, 26]. The proof of our main theorem will now follow a new approach, combining physical space estimates with Fourier based estimates exploited in the scattering theory developed in [44].

In the rest of the introduction we will give some background on the problem and formulate our main result Theorem 1.

The Cauchy horizon and the Strong Cosmic Censorship Conjecture. The main motivation for studying linear waves on black hole interiors is to shed light on one of the most fundamental puzzles in general relativity: The Kerr(–de Sitter or –Anti-de Sitter) and Reissner–Nordström (–de Sitter or –Anti-de Sitter) black holes share the property that in addition to the event horizon\({\mathcal {H}}\), they hide another horizon, the so-called Cauchy horizon\(\mathcal {CH}\), in their interiors.Footnote 1 This Cauchy horizon defines the boundary beyond which initial data on a spacelike hypersurface (together with boundary conditions at infinity in the asymptotically AdS case) no longer uniquely determine the spacetime as a solution of (EE). In particular, these spacetimes admit infinitely many smooth extensions beyond their Cauchy horizons solving (EE). This severe violation of determinism is conjectured to be an artifact of the high degree of symmetry in those explicit spacetimes and generically, due to blue-shift instabilities, it is expected that a singularity ought to form at or before the Cauchy horizon. This is known as the Strong Cosmic Censorship Conjecture (SCC) [9, 57]. A full resolution of the SCC conjecture would also include a precise description of the breakdown of regularity at or before the Cauchy horizon.

We first present the \(C^0\) formulation of SCC (see [9, 17]), which can be seen as the strongest inextendibility statement in this context.

Conjecture 1

(\(C^0\)formulation of strong cosmic censorship). For generic compact or asymptotically flat (asymptotically Anti-de Sitter) vacuum initial data, the maximal Cauchy development of (EE) is inextendible as a Lorentzian manifold with \(C^0\) (continuous) metric.

Surprisingly, the \(C^0\) formulation (Conjecture 1) was recently proved to be false for both cases \(\Lambda =0\) and \(\Lambda >0\) (see discussion later, [17]). However, the following weaker, yet well-motivated, formulation introduced by Christodoulou in [9] is still expected to hold true (at least) in the asymptotically flat case (\(\Lambda =0\)).

Conjecture 2

(Christodoulou’s re-formulation of strong cosmic censorship). For generic asymptotically flat vacuum initial data, the maximal Cauchy development of (EE) is inextendible as a Lorentzian manifold with \(C^0\) (continuous) metric and locally square integrable Christoffel symbols.

In order to gain insight about SCC, the most naive approach (often referred to as “poor man’s linearization”) is to study solutions of (1.1) with \(\mu =0\) on a fixed explicit black hole spacetime (e.g. Kerr or Reissner–Nordström). This can be considered as the most naive toy model for (EE) with initial data close to Kerr or Reissner–Nordström data, for which many features of (EE) including the non-linear terms and the tensorial structure are neglected; see the pioneering works for asymptotically flat (\(\Lambda =0\)) black holes [8, 49, 50, 60]. Under the identification \(\psi \sim g\) and \(\partial \psi \sim \Gamma \), where \(\psi \) is a solution to (1.1), Conjecture 1 corresponds to a failure of \(\psi \) to be continuous (\(C^0\)) at the Cauchy horizon. Similarly, Conjecture 2 corresponds to a failure of \(\psi \) to lie in \(H^1_\mathrm {loc}\) at the Cauchy horizon.

The state of the art for\(\Lambda =0\)and\(\Lambda >0\). The definitive disproof [17] of Conjecture 1 was preceded by corresponding results on the level of (1.1).

Linear level for\(\Lambda =0\). In the asymptotically flat case (\(\Lambda =0\)) it was shown in [26, 27] (see also [35]) that solutions of (1.1) with \(\mu =0\) arising from data on a spacelike hypersurface remain continuous and uniformly bounded (no \(C^0\) blow-up) at the Cauchy horizon of general subextremal Kerr or Reissner–Nordström black hole interiors. (For the extremal case see [30, 31].) The key method for the proof is to use the polynomial decay on the event horizon proved in [19] (with rate \(|\psi | \lesssim v^{-p}\) and \(p>1\)) and propagate it into the interior. The boundedness and continuity of \(\psi \) at the Cauchy horizon was then concluded from red-shift estimates, energy estimates associated to the novel vector field

and commuting with angular momentum operators followed by Sobolev embeddings. Here u, v are Eddington–Finkelstein-type null coordinates in the interior.

Besides the above \(C^0\) boundedness, it was proved that the (non-degenerate) local energy at the Cauchy horizon blows up for a generic set of solutions \(\psi \) in Reissner–Nordström [45] and Kerr [20] black holes. (Note that this blow-up is compatible with the finiteness of the flux associated to (1.2) because \(\partial _v\) and \(\partial _u\) degenerate at the Cauchy horizons \(\mathcal {CH}_A\) and \(\mathcal {CH}_B\), respectively.) A similar blow-up behavior was obtained for Kerr in [48] assuming lower bounds on the energy decay rate of a solution along the event horizon. These results support Conjecture 2 at least on the level of (1.1).

Another type of result that has been shown in [44] is a finite energy scattering theory for solutions of (1.1) (with \(\mu =0\)) from the event horizon \({\mathcal {H}}_A^+ \cup {\mathcal {H}}_B^+\) to the Cauchy horizon \(\mathcal {CH}_A \cup \mathcal {CH}_B\) in the interior of Reissner–Nordström black holes. In this scattering theory a linear isomorphism between the degenerate energy spaces (associated to the Killing field \(T = \partial _ v - \partial _u\)) corresponding to the event and Cauchy horizon was established. The question reduced to obtaining uniform control over transmission and reflection coefficients \({\mathfrak {T}}(\omega ,\ell )\) and \({\mathfrak {R}}(\omega ,\ell )\) corresponding to fixed frequency solutions. Intuitively, for a purely incoming wave at the event horizon \({\mathcal {H}}_A^+\), the transmission and reflection coefficients correspond to the amount of T-energy scattered to \(\mathcal {CH}_B\) and \(\mathcal {CH}_A\), respectively. Indeed, the theory also carries over to \(\Lambda \ne 0\) and \(\mu \ne 0\)except for the \(\omega =0\) frequency. This will turn out to be important for the present paper.

Linear level for\(\Lambda >0\). For Kerr(and Reissner–Nordström)–de Sitter (\(\Lambda >0\)) it was shown in [36] that solutions of (1.1) (with \(\mu =0\)) also remain bounded up to and including the Cauchy horizon. Note that in both cases, \(\Lambda =0\) and \(\Lambda >0\), the proofs rely crucially on quantitative decay along the event horizon (polynomial for \(\Lambda =0\) and exponential for \(\Lambda >0\)).

On the other hand the exponential convergence on the event horizon of a Kerr–de Sitter black hole is in direct competition with the exponential blue-shift instability and the question of local energy blow-up at the Cauchy horizon for (1.1) is more subtle, see the conjecture in [15] and the more recent [21,22,23].

Nonlinear level for\(\Lambda =0\)and\(\Lambda >0\). Now we turn to the full nonlinear problem for (EE). As mentioned before, for the Einstein vacuum equations Dafermos–Luk showed that the Kerr Cauchy horizon is \(C^0\) stable [17], i.e. the spacetime is extendible as a \(C^0\) Lorentzian manifold. Note that this definitively falsifies Conjecture 1 for \(\Lambda =0\) (subject only to the completion of a proof of the nonlinear stability of the Kerr exterior). In principle, their proof of \(C^0\) extendibility also applies to the interior of Kerr–de Sitter black holes, where the exterior has been proved to be stable for slowly rotating Kerr–de Sitter black holes [37], thus falsifying Conjecture 1 for \(\Lambda >0\).

Nonlinear inextendibility results at the Cauchy horizon have been proved only in spherical symmetry: Coupling the Einstein equation (EE) to a Maxwell–Scalar field system, it is proved in [14] that the Cauchy horizon is \(C^0\) stable, yet \(C^2\) unstable [14, 46, 47] for a generic set of spherically symmetric initial data. See also the pioneering work in [56, 58]. This shows the \(C^2\) formulation of SCC (but not yet Conjecture 2) in spherical symmetry. See [12, 13] for work in the \(\Lambda >0\) case. The question of any type of nonlinear instability of the Cauchy horizon without symmetry assumptions and the validity of Conjecture 2 (even restricted to a neighborhood of Kerr) have yet to be understood.

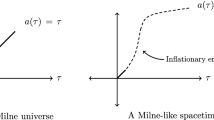

Linear waves and SCC for asymptotically AdS black holes. The situation is changed radically if one considers asymptotically Anti-de Sitter (\(\Lambda <0\)) spacetimes. Due to the timelike nature of null infinity \({\mathcal {I}} = {\mathcal {I}}_A \cup {\mathcal {I}}_B \), see for example Fig. 1, these spacetimes are not globally hyperbolic. For well-posedness of (EE) and (1.1) it is required to impose also boundary conditions at infinity. The most natural conditions are Dirichlet (reflecting) boundary conditions, see [29]. Before we address the question of stability of the Cauchy horizon, it is essential to understand the behavior in the exterior region of Kerr–AdS or Reissner–Nordström–AdS.

Logarithmic decay for linear waves on the exterior of Kerr–AdS and Reissner–Nordström–AdS. For the massive linear wave equation (1.1) on Kerr–AdS and Reissner–Nordström–AdS, Holzegel–Smulevici showed in [40] stability in the exterior region. Indeed, they proved that solutions decay at least at logarithmic rate towards \(i^+\) (cf. polynomial (\(\Lambda =0\)) and exponential (\(\Lambda >0\))) assuming the Hawking–Reall [34] boundFootnote 2\(r_+ > |a|l\) and the Breitenlohner–Freedman [6] bound \(\mu > \frac{3}{4}\Lambda \). Moreover, they showed that solutions of (1.1) with fixed angular momentum actually decay exponentially on the exterior of Reissner–Nordström–AdS. (This is in contrast to the asymptotically flat case, in which fixed angular momentum solutions of (1.1) decay polynomially on the exterior of Reissner–Nordström.) However, their main insight was that a suitable infinite sum of such rapidly decaying fixed angular momentum solutions, possessing finite energy in some weighted norm, indeed achieves the logarithmic decay rate [42]. This is due to the presence of stable trapping. Note that this sharpness can also be concluded from later work showing the existence of quasinormal modes converging to the real axis at an exponential rate as the real part of the frequency and angular momentum tend to infinity [32, 64]. (For some asymptotically flat five dimensional black holes a similar inverse logarithmic lower bound was shown in [2].)

Strong Cosmic Censorship for AdS black holes. With the logarithmic decay on the exterior in hand, we turn to the question of the stability of the Cauchy horizon. Indeed, the logarithmic decay rate on the exterior is too slow to follow the methods involving the red-shift vector field and the vector field S as in (1.2) (see discussion before) to prove uniform boundedness and \(C^0\) (continuous) extendibility at the Cauchy horizon of solutions to (1.1). More specifically, after propagating the logarithmic decay through the red-shift region, the energy flux associated to S is infinite on a \(\{ r= const.\}\) hypersurface in the black hole interior due to the slow logarithmic decay towards \(i^+\). Thus, the question of whether to expect the validity of Conjecture 1 for asymptotically AdS black holes appears to be completely open. (See also the paragraph in the end of the introduction discussion a possible nonlinear instability in the exterior.)

The present paper is an attempt to shed some first light on SCC in the asymptotically AdS case: We will show (Theorem 1) that, despite the slow decay on the exterior, boundedness in the interior and continuous extendibility to the Cauchy horizon still holds for solutions of (1.1) on Reissner–Nordström–AdS black holes. The additional phenomenon which we exploit to prove boundedness is that the trapped frequencies responsible for slow decay have high energy with respect to the T vector field and can be bounded using the scattering theory developed in [44]. Thus, for Reissner–Nordström–AdS, the analog of Conjecture 1 is false on the linear level, just as in the \(\Lambda \ge 0\) cases. See however our remarks on Kerr–AdS later in the introduction.

The massive linear wave equation on Reissner–Nordström–AdS. As mentioned above, we will consider the massive linear wave equation

for AdS radius \(l^2 := - \frac{3}{\Lambda }\) on a fixed subextremal Reissner–Nordström–AdS black hole with mass parameter \(M>0\) and charge parameter \(0<|Q|<M\). Moreover, we assume the so-called Breitenlohner–Freedman bound [6] for the Klein–Gordon mass parameter \(\alpha <\frac{9}{4}\), which includes the conformally invariant case \(\alpha =2\). This bound is required to obtain well-posedness [39, 62, 63] of (1.3).

Recall from the discussion above that solutions with fixed angular momentum \(\ell \) actually decay exponentially in the exterior region. For such solutions with fixed \(\ell \), uniform boundedness with upper bound \(C=C_\ell \) in the interior and continuity at the Cauchy horizon can be shown using the methods involving the vector field S as in (1.2). Note however that this does not imply that a general solution remains bounded in the interior as the constant \(C_\ell \) is not summable: \( \sum _{\ell =0}^{L} C_\ell \sim e^{ L} \rightarrow + \infty \) as \(L\rightarrow \infty \). Note in particular that, as a result of this, one cannot study the new non-trivial aspect of this problem restricted to spherical symmetry. (Nevertheless, see [3] for a discussion of the Ori model for RN–AdS black holes.)

Main theorem: Uniform boundedness and continuity at the Cauchy horizon. We now state a rough version of our main result. See Theorem 3.1 for the precise statement.

Theorem 1

(Rough version of Theorem 3.1). Let \(\psi \) be a solution to (1.3) arising from smooth and compactly supported initial data \((\psi _0,\psi _1)\) posed on a spacelike hypersurface \(\Sigma _0\) as depicted in Fig. 1. Then, \(\psi \) remains uniformly bounded in the black hole interior

where C is constant depending on the parameters \(M,Q,l,\alpha \), the choice of \(\Sigma _0\) and on some higher order Sobolev norm of the initial data \((\psi _0,\psi _1)\). Moreover, \(\psi \) can be extended continuously across the Cauchy horizon.

As we have explained above, the main difficulty compared to the asymptotically flat case, where the analysis was carried out entirely in physical space and requires inverse polynomial decay in the exterior [26], is the slow decay of \(\psi \) along the event horizon. Our strategy is to decompose the solution \(\psi \) in a low and high frequency part \(\psi = \psi _\flat + \psi _\sharp \) with respect to the Killing field \(T =\frac{\partial }{\partial t}\) and treat each term separately.

For the low frequency part \(\psi _\flat \), we will show a superpolynomial decay rate in the exterior, see already Proposition 4.8. For this part we also use integrated energy decay estimates for bounded angular momenta \(\ell \) established in [40]. This superpolynomial decay in the exterior is sufficient so as to follow the method of [26] with vector fields of the form (1.2) to show boundedness and continuity at the Cauchy horizon, up to the additional difficulty caused by the fact that we allow a possibly negative Klein–Gordon mass parameter. The violation of the dominant energy condition due to the presence of a negative mass term can be overcome with twisted derivatives [43, 63], which provide a useful framework to replace Hardy inequalities for the lower order terms in this context.

For the high frequency part \(\psi _\sharp \), which is exposed to stable trapping and does in general only decay at a sharp logarithmic rate in the exterior, the key ingredient is the scattering theory developed in [44] (see discussion above). More specifically, the uniform bounds for the transmission and reflections coefficients \({\mathfrak {T}}\) and \({\mathfrak {R}}\) for \(|\omega | \ge \omega _0\) proved in [44] turn out to be useful for the high frequency part \(\psi _\sharp \). These bounds allow us to control \(|\psi _\sharp |\) at the Cauchy horizon by the T-energy norm on the event horizon commuted with angular derivatives. The T-energy flux on the event horizon is in turn bounded from initial data by a simple application of the T-energy identity in the exterior. In particular, no quantitative decay along the event horizon is used for the high frequency part\(\psi _\sharp \). This is what allows us to overcome the problem of slow logarithmic decay.

Outlook on Kerr–AdS. We strongly believe that our arguments also apply to axially symmetric solutions \(\psi \) of (1.3) on a Kerr–AdS black hole. For general non-axisymmetric solutions, however, the question of uniform boundedness and continuity at the Cauchy horizon is less clear. Indeed, specific high frequency solutions which decay at a logarithmic decay rate can be considered as “low frequency” solutions when frequency is measured with respect to the Killing generator of the Cauchy horizon. In fact, it might well be the case that for solutions of (1.3) on Kerr–AdS there is \(C^0\) blow-up at the Cauchy horizon, supporting the validity of Conjecture 1 after all in this context!

Instability of asymptotically AdS spacetimes? Turning to the fully nonlinear dynamics, there is another scenario which could happen. Recall that Minkowski space (\(\Lambda =0\)) and de Sitter space (\(\Lambda >0\)) have been proved to be nonlinearly stable [10, 28]. Anti-de Sitter space (\(\Lambda <0\)), however, is expected to be nonlinearly unstable with Dirichlet conditions imposed at infinity. This was recently proved in [51,52,53,54] for appropriate matter models. See also the original conjecture in [16] and the numerical results in [4]. Similarly, for Kerr–AdS (or Reissner–Nordström–AdS), the slow logarithmic decay on the linear level proved in [42] could in fact give rise to nonlinear instabilities in the exterior.Footnote 3 If indeed the exterior of Kerr–AdS was nonlinearly unstable, linear analysis like that in the present paper would be manifestly inadequate and the question of the validity of Strong Cosmic Censorship would be thrown even more open! Refer to the introduction of [17] for a more elaborate discussion.

Outline. This paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2 we set up the spacetime and summarize relevant previous work. In Sect. 3 we state and prove our main result Theorem 3.1. Parts of the proof require a separate analysis which are treated in Sects. 4 and 5.

2 Preliminaries

We start by setting up the Reissner–Nordström–AdS spacetime (see [7]) and defining relevant norms and energies. We will also introduce useful coordinate systems.

2.1 The Reissner–Nordström–AdS black hole

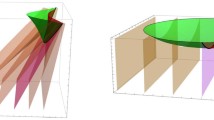

We are ultimately interested in the behavior of solutions to (1.3) to the future of a spacelike hypersurface \(\Sigma _0\) as depicted in Fig. 1. For technical reasons (Fourier space decompositions are non-local operations) we will however construct also parts to the past of \(\Sigma _0\). In the following will define the spacetime pictured in Fig. 2.

2.1.1 Construction of the spacetime \(({\mathcal {M}}_\mathrm {RNAdS},g_{\mathrm {RNAdS}})\).

First, for black hole parameters \(M>0, Q\ne 0, l^2\ne 0\) define the polynomial

and define the non-degenerate set

Note that \({\mathcal {P}}\) defines black hole parameters in the subextremal range. From now on, we will consider fixed parameters \(M,Q,l,\alpha \), where

Note that M is the mass parameter, Q the charge parameter of the black hole and \(l = \sqrt{-\frac{3}{\Lambda }}\) is the Anti-de Sitter radius. For this specific choice of parameters we will also write \(\Delta (r):= \Delta _{M,Q,l}(r)\) and denote by \(0<r_-<r_+\) the positive roots of \(\Delta \).

Now, let the two exterior regions \({\mathcal {R}}_A\), \({\mathcal {R}}_B\) and the black hole region \({\mathcal {B}}\) be smooth four dimensional manifolds diffeomorphic to \({\mathbb {R}}^2 \times {\mathbb {S}}^2\). On \({\mathcal {R}}_A, {\mathcal {R}}_B\) and \({\mathcal {B}}\) we introduce globalFootnote 4 coordinate charts:

If it is clear from the context which coordinates are being used, we will omit their subscripts throughout the paper. Again, on the manifolds \({\mathcal {R}}_A,{\mathcal {R}}_B\) and \({\mathcal {B}}\) we define—using the coordinates \((t,r,\theta ,\varphi )\) on each of the patches—the Reissner–Nordström–Anti-de Sitter metric

On each of \({\mathcal {R}}_A,{\mathcal {R}}_B\) and \({\mathcal {B}}\), we define time orientations using the vector field \(\partial _{t_{{\mathcal {R}}_A}}\) on \({\mathcal {R}}_A\), \(-\partial _{t_{{\mathcal {R}}_B}}\) on \({\mathcal {R}}_B\) and \(-\partial _{r_{\mathcal {B}}}\) on \({\mathcal {B}}\).

We will also define the tortoise coordinate \(r_*\) by

in \({\mathcal {R}}_A\), \({\mathcal {R}}_B\) and \({\mathcal {B}}\) independently. This defines \(r_*\) up to an unimportant constant. Then, in each of the regions \({\mathcal {R}}_A\), \({\mathcal {R}}_B\) and \({\mathcal {B}}\), we define null coordinates by

where for example for the v coordinate on \({\mathcal {R}}_A\), we will use the notation \(v_{{\mathcal {R}}_A}\) and analogously for the other regions. Note that throughout the paper we will use the notation \(^\prime \) for derivatives \(\frac{\partial }{\partial r_*}\).

Patching the regions\({\mathcal {R}}_A,{\mathcal {R}}_B\)and\({\mathcal {B}}\)together. Now, we patch the regions \({\mathcal {R}}_A\), \({\mathcal {R}}_B\) and \({\mathcal {B}}\) together. We begin by attaching the future (resp. past) event horizon \({\mathcal {H}}_A^+\) (resp. \({\mathcal {H}}_A^-\)) to \({\mathcal {R}}_A\) by formallyFootnote 5 setting

Similarly, we attach \({\mathcal {H}}_B^+ := \{ v_{{\mathcal {R}}_B} = -\infty \}\) and \({\mathcal {H}}_B^- := \{ u_{{\mathcal {R}}_B} = -\infty \}\) to \({\mathcal {R}}_B\). In the \((u_{\mathcal {B}},v_{\mathcal {B}})\) coordinates associated to \({\mathcal {B}}\) we make the identifications \({\mathcal {H}}_A^+ = \{ u_{{\mathcal {B}}} = - \infty \}\) and \({\mathcal {H}}_B^+ = \{ v_{{\mathcal {B}}} =-\infty \}\). Then, we attach the Cauchy horizon \(\mathcal {CH}_A:= \{ v_{{\mathcal {B}}} = + \infty \}\) and \(\mathcal {CH}_B := \{ u_{{\mathcal {B}}} = + \infty \}\) to \({\mathcal {B}}\).

Finally, we attach the past (resp. future) bifurcation sphere \({\mathcal {B}}_-\) (resp. \({\mathcal {B}}_+\)) to \({\mathcal {B}}\) as

We shall also set \(\mathcal {CH}:= \mathcal {CH}_A \cup \mathcal {CH}_B\cup {\mathcal {B}}_+\). Note that all horizons \({\mathcal {H}}_A^+, {\mathcal {H}}_A^-, {\mathcal {H}}_B^+, {\mathcal {H}}_B^-, \mathcal {CH}_A\), and \(\mathcal {CH}_B\) are diffeomorphic to \({\mathbb {R}} \times {\mathbb {S}}^2\) and the past (future) bifurcation sphere \({\mathcal {B}}_-\) (\({\mathcal {B}}_+\)) is diffeomorphic to \({\mathbb {S}}^2\). Moreover, we identify \({\mathcal {B}}_-\) with \( \{ u_{{\mathcal {R}}_A} = -\infty , v_{{\mathcal {R}}_A} = -\infty \} \) and also with \( \{ u_{{\mathcal {R}}_B} = -\infty , v_{{\mathcal {R}}_B} = -\infty \} \). The resulting manifold will be called \({\mathcal {M}}_{\mathrm {RNAdS}}\). Note that, g extends to a smooth Lorentzian metric on \(\mathcal M_{\mathrm {RNAdS}}\) which we will call \(g_{\mathrm {RNAdS}}\) and in particular, \(({\mathcal {M}}_{\mathrm {RNAdS}},g_{\mathrm {RNAdS}})\) is a time oriented smooth Lorentzian manifold with corners. We illustrate the constructed spacetime as a Penrose diagram in Fig. 2. Note that the vector field \(\partial _t\) defined on \({\mathcal {R}}_A\), \({\mathcal {R}}_B\) and \({\mathcal {B}}\), respectively, extends to a smooth Killing field on \({\mathcal {M}}_{\mathrm {RNAdS}}\), which we will from now on call T. Moreover, the standard angular momentum operators \({\mathcal {W}}_i\) for \(i=1,2,3\), the generators of \(\mathfrak {so}(3)\) defined as

are Killing vector fields. It shall be noted that \({\mathcal {W}}_i\) for \(i=1,2,3\) are spacelike everywhere, whereas T is future-directed timelike on \({\mathcal {R}}_A\), spacelike on \({\mathcal {B}}\) and past-directed timelike on \({\mathcal {R}}_B\). Moreover, T is future-directed null on \({\mathcal {H}}_A^-,{\mathcal {H}}_A^+, \mathcal {CH}_B\), past-directed null on \({\mathcal {H}}_B^-,{\mathcal {H}}_B^+, \mathcal {CH}_A\) and vanishes on \({\mathcal {B}}_-,{\mathcal {B}}_+\). Finally, note that one can attach conformal timelike boundaries \({\mathcal {I}}_A\) and \({\mathcal {I}}_B\) corresponding to \(\{r_{{\mathcal {R}}_A} =+\infty \}\) and \(\{ r_{{\mathcal {R}}_B} = +\infty \}\), respectively.Footnote 6

2.1.2 Initial hypersurface \(\Sigma _0\).

We will impose initial data on a spacelike hypersurface \(\Sigma _0\) to be made precise in the following. Note that we can choose for convenience that the spacelike hypersurface \(\Sigma _0\) lies to the future of the past bifurcation sphere \({\mathcal {B}}_-\). Indeed, by general theory (an energy estimate in a compact region) this can be assumed without loss of generality [18]. More precisely, let \(\Sigma _0\) be a 3 dimensional connected, complete and spherically symmetric spacelike hypersurface extending to the conformal infinity \({\mathcal {I}} ={\mathcal {I}}_A \cup {\mathcal {I}}_B\). Moreover, assume that \({\mathcal {B}}_- \subset J^-(\Sigma _0){\setminus } \Sigma _0\).

A possible choice of \(\Sigma _0\) is denoted in Fig. 3. We are ultimately interested in the shaded region to the future of \(\Sigma _0\). For the rest of the paper, we will consider such a \(\Sigma _0\) to be fixed.

2.2 Conventions

With \(a\lesssim b\) for \(a\in {\mathbb {R}}\) and \(b\ge 0\) we mean that there exists a constant \(C(M,Q,l,\alpha , \Sigma _0)\) with \(a\le C b\). If \(C(M,Q,l,\alpha , \Sigma _0)\) depends on an additional parameter, say \(\ell \), we will write \(a \lesssim _\ell b\). We also use \(a\sim b\) for some \(a,b\ge 0\) if there exist constants \(C_1(M,Q,l,\alpha ,\Sigma _0), C_2(M,Q,l,\alpha ,\Sigma _0) >0\) with \(C_1 a \le b \le C_2 a\). We shall also make use of the standard Landau notation O and o [55]. To be more precise, let X be a point set (e.g. \(X={\mathbb {R}}, [a,b], {\mathbb {C}}\)) with limit point c. As \(x\rightarrow c\) in X, \(f(x) = O(g(x))\) means \(\frac{|f(x)|}{|g(x)|} \le C(M,Q,l,\alpha )\) holds in a fixed neighborhood of c. We write \(O_\ell (g(x))\) if the constant C depends on an additional parameter \(\ell \). For the standard volume form in spherical coordinates \((\varphi ,\theta )\) on the sphere \({\mathbb {S}}^2\) we will use the notation \(\mathrm {d}\sigma _{{\mathbb {S}}^2} := \sin \theta \mathrm {d}\varphi \mathrm {d}\theta \). Finally, let the Japanese symbol be defined as \(\langle x \rangle := \sqrt{ 1+ x^2 }\) for \(x \in \mathbb R\).

2.3 Norms and Energies

We are interested in solutions to the massive wave equation (1.3) associated to the metric \(g_{\mathrm {RNAdS}}\) on a subextremal Reissner–Nordström AdS black hole with black hole parameters M, Q, l as in (2.3). In view of the timelike boundaries \({\mathcal {I}}_A\) and \({\mathcal {I}}_B\), we need to specify boundary conditions on \({\mathcal {I}}_A\) and \({\mathcal {I}}_B\) in addition to prescribing data on the spacelike hypersurface \({\Sigma }_0\), cf. Fig. 3. We will use Dirichlet (reflecting) boundary conditions which can be viewed as the most natural conditions in the context of stability of the Cauchy horizon. In principle, however, in view of [63], we could also use more general boundary conditions like Neumann or Robin conditions. We will now introduce an appropriate foliation and norms in order to state the well-posedness statement in Sect. 2.4.

We will foliate \({\mathcal {R}}_A \cup {\mathcal {R}}_B \cup {\mathcal {H}}_A^+\cup {\mathcal {H}}_B^+ \cup {\mathcal {B}}\) with spacelike hypersurfaces. To do so, we let \({\mathcal {T}}\) be a smooth future-directed causal vector field on \({\mathcal {R}}_A \cup {\mathcal {R}}_B \cup {\mathcal {H}}_A^+\cup {\mathcal {H}}_B^+ \cup {\mathcal {B}}\) with the properties that

and that \({\mathcal {T}}\) is a future-directed timelike vector field on \({\mathcal {B}}\). Now, define the leaves

where \(\Phi ^{{\mathcal {T}}}\) is the flow generated by \({\mathcal {T}}\) and \(t^*\in {\mathbb {R}}\) is its affine parameter. We have illustrated some leaves in Fig. 4.

Illustration of the foliation with leaves \(\Sigma _\tau \) defined in (2.11)

2.3.1 Further coordinates in the exterior region.

In the region \({\mathcal {R}}_A \cup {\mathcal {H}}_A^+\), we moreover define a global (up to the well-known degeneracy on \({\mathbb {S}}^2\)) coordinate system \((t^*,r,\varphi ,\theta )\), where \(t^*\) is the affine parameter of the flow generated by \({\mathcal {T}}\). Note that on \({\mathcal {R}}_A \cup {\mathcal {H}}_A^+\) we have \(\partial _{t^*} =T\) such that \(t^*( t_2,r) - t^*(t_1,r) = t_2 - t_1\) and \(t(t_2^*,r ) - t(t_1^*,r) = t_2^*- t_1^*\). Similarly, we can define such a coordinate system on \({\mathcal {R}}_B\).

2.3.2 Norms on hypersurfaces \(\Sigma _{t^*}\).

By construction \(\Sigma _{t^*}\) intersects \({\mathcal {R}}_A\), \({\mathcal {R}}_B\) and \({\mathcal {B}}\). We will now define norms on \(\Sigma _{t^*}\) which are adaptations of the norms introduced in [39]. We define

and

where each of the terms appearing in (2.12) will be defined in the following.

Norms in the interior region. We begin by defining the first term in (2.12). We define \(\Vert \cdot \Vert ^2_{H^k(\Sigma _{t^*} \cap {\mathcal {B}})}\) as the standard Sobolev norm of order k on the Riemannian manifold \((\Sigma _{t^*}\cap {\mathcal {B}},g_{\mathrm {RNAdS}}\upharpoonright _{\Sigma _{t^*}\cap {\mathcal {B}}})\).

Norms in the exterior region. Due to the symmetry of the regions \({\mathcal {R}}_A\) and \({\mathcal {R}}_B\), we will only define the norms on \({\mathcal {R}}_A\) in the following. The norms on \({\mathcal {R}}_B\) are be constructed analogously. We use the coordinates \((t^*, r, \theta ,\varphi )\) in \({\mathcal {R}}_A\) to define the norms

and similarly for higher order norms. Here and in the following we denote with  and

and  the induced covariant derivative and the induced metric, respectively, on spheres of constant (\(t^*,r\)). We will also use the notation

the induced covariant derivative and the induced metric, respectively, on spheres of constant (\(t^*,r\)). We will also use the notation  . Now having defined (2.12), we will define energies in the following.

. Now having defined (2.12), we will define energies in the following.

2.3.3 Energies on hypersurfaces \(\Sigma _{t^*}\).

We set

for \(i=1,2\), where all terms in (2.14) will be defined in the following.

Energies in the interior region. In the interior region we are not concerned with r-weights and define the energies as

Energies in the exterior region. To define the energies in the exterior region, it is convenient to start with defining the following energy densities

and their integrals as

for \(i = 1,2\). Note that we will write \(E_i^B\) for the analogous energy restricted to \({\mathcal {R}}_B\).

Also remark the following relation between the norms and energies defined above

2.4 Well-posedness and mixed boundary value Cauchy problem

Having set up the spacetime and the norms, we will restate the well-posedness result for (1.3) as a mixed boundary value-Cauchy problem. For asymptotically AdS spacetimes, well-posedness was first proved in [39].

Theorem 2.1

[39]. Let the Reissner–Nordström–AdS parameters (M, Q, l) and the Klein–Gordon mass \(\alpha < \frac{9}{4}\) be as in (2.3). Let initial data \((\psi _0 ,\psi _1)\in C_c^\infty (\Sigma _0) \times C_c^\infty (\Sigma _0) \) be prescribed on the spacelike hypersurface \(\Sigma _0\) and impose Dirichlet (reflecting) boundary conditions on \({\mathcal {I}}= {\mathcal {I}}_A \cup {\mathcal {I}}_B\).

Then, there exists a smooth solution \(\psi \in C^\infty ({\mathcal {M}}_\mathrm {RNAdS}{\setminus } \mathcal {CH})\) of (1.3) such that \(\psi \upharpoonright _{\Sigma _0} = \psi _0\), \({\mathcal {T}}\psi \upharpoonright _{\Sigma _0} = \psi _1\). The solution \(\psi \) is also unique in the class \(C({\mathbb {R}}_{t^*};H^{1,0}_{\mathrm {RNAdS}}(\Sigma _{t^*}))\cap C^1({\mathbb {R}}_{t^*}; H^{0,-2}(\Sigma _{t^*}))\).

Remark 2.2

The well-posedness statement in Proposition 2.1 holds true for a more general class of initial data, called a \(H^2_{\mathrm {AdS}}\) initial data triplet which give rise to a solution in \(CH_{\mathrm {RNAdS}}^2\), see [39].

2.5 Energy identities and estimates

In order to prove energy estimates, it turns out to be useful to introduce two types of energy-momentum tensors. Besides the standard energy-momentum tensor associated to (1.3), a suitable twisted energy-momentum tensor plays an important role in our estimates. Indeed, due to the negative mass term, the standard energy-momentum tensor does not satisfy the dominant energy condition. However, the dominant energy condition can be restored for the twisted energy-momentum tensor introduced in [6, 63]. In particular, these twisted energies will be used in the interior region, whereas in the exterior region we will work with the standard energy-momentum tensor. We will first review the energy estimates in the exterior.

2.5.1 Energy estimates in the exterior region.

Energy-momentum tensor. For a smooth function \(\phi \) we define

For a smooth vector field X we also define

where \({}^X\pi := {\mathcal {L}}_X g\) is the deformation tensor. The term \(K^X\) is often referred to as the “bulk term” and satisfies

if \(\phi \) is a solution to (1.3). Note that if X is Killing, then \(K^X\) vanishes. More generally, integrating (2.20) one obtains an energy identity relating boundary and bulk terms. For more details about the energy-momentum tensor and its usage for standard energy estimates we refer to [18].

Boundedness and decay in the exterior region. In the exterior regions \({\mathcal {R}}_A\) and \({\mathcal {R}}_B\) we have energy decay and boundedness results which have been proved in [38,39,40, 42].Footnote 7 To state them we make the following choice of volume forms and normals on the event horizon. We set \(\mathrm {dvol}_{{\mathcal {H}}_A^+} = r^2 \mathrm {d}t^*\mathrm {d}\sigma _{{\mathbb {S}}^2}\) and \(n_{{\mathcal {H}}_A^+} = T\) and similarly for \({\mathcal {H}}_B^+\). Moreover, we denote by \(\mathrm {dvol}_{\Sigma _{t^*}} \sim r \mathrm {d}r \sin \theta \mathrm {d}\theta \mathrm {d}\varphi \) the induced volume form on the spacelike hypersurface \(\Sigma _{t^*}\cap {\mathcal {R}}_A\) and by \(n^\mu _{\Sigma _t^*}\) its future-directed unit normal. We summarize these energy identities and estimates in the following.

Proposition 2.3

[39]. A solution \(\psi \) to (1.3) arising from smooth and compactly supported data on \(\Sigma _0\) as in Proposition 2.1 satisfies

where \(t^*_1 \le t^*_2\) and \({\mathcal {H}}_A^+ (t_1^*,t_2^*):= {\mathcal {H}}_A^+ \cap \{t_1^*\le t^*\le t_2^*\}\). The analogous energy identity holds in \({\mathcal {R}}_B\). In particular, (2.21) shows that the T-energy flux through \({\mathcal {I}}={\mathcal {I}}_A \cup {\mathcal {I}}_B\) vanishes.

Moreover, the T-energy flux through the event horizon is bounded by initial data

Finally, note that

Remark that (2.23) follows from a Hardy inequality (see [38, Equation (50)]) which is used to absorb the (possibly) negative contribution from the Klein–Gordon mass term.

Theorem 2.4

[42, Theorem 1.1], [40, Section 12]. A solution \(\psi \) to (1.3) arising from smooth and compactly supported data on \(\Sigma _0\) as in Proposition 2.1 satisfies

and similarly for higher order norms. Moreover, we have the energy decay statements

for \(t^*\ge 0\) and the pointwise decay

for \(t^*\ge 0\) in the exterior region \({\mathcal {R}}_A\) and similarly in \({\mathcal {R}}_B\). Moreover, just like for Schwarzschild–AdS (cf. [40]), fixed angular frequencies decay exponentially. More precisely, let \(Y_{\ell m}\) denote the spherical harmonics and let \(\psi \) be a solution to (1.3) arising from smooth and compactly supported data on \(\Sigma _0\). If there exists an \(L\in {\mathbb {N}}\) with \(\langle \psi ,Y_{m\ell } \rangle _{L^2({\mathbb {S}}^2)} =0 \) for \(\ell \ge L\), then

for \(t^*\ge 0\) and a constant \( C(M,Q,l,\alpha )>0\) only depending on the parameters \(M,Q,l,\alpha \).

Remark 2.5

Note that (2.28) also implies pointwise exponential decay for \(\psi \) (assuming \(\langle \psi ,Y_{\ell m} \rangle _{L^2({\mathbb {S}}^2)} =0 \) for \(\ell \ge L\)) and all higher derivatives of \(\psi \) using standard techniques like commuting with T and \({\mathcal {W}}_i\), elliptic estimates as well as applying a Sobolev embedding. Moreover, the previous estimates above also hold true for a the more general class of solutions \(CH_{\mathrm {RNAdS}}^2\). See [39] or [40, Theorem 4.1] for more details.

Remark 2.6

The previous decay estimates have only been stated to the future of \(\Sigma _0\) in the region \({\mathcal {R}}_A\), nevertheless, they also hold in \({\mathcal {R}}_B\). Moreover, they also hold true to the past of \(\Sigma _0\) for an appropriate foliation for which the leaves intersect \({\mathcal {H}}_A^-\) and \({\mathcal {H}}_B^-\), and are transported along the flow of \(-T\) for \({\mathcal {R}}_A\cup {\mathcal {H}}_A^- \) and along the flow of T for \({\mathcal {R}}_B\cup {\mathcal {H}}_B^-\).

We now turn to the energy estimates in the interior region \({\mathcal {B}}\).

2.5.2 Energy estimates in the interior region.

Twisted energy-momentum tensor. We begin by defining twisted derivatives.

Definition 2.7

(Twisted derivative). For a smooth and nowhere vanishing function f we define the twisted derivative

and its formal adjoint

We shall refer to f as the twisting function.

Remark 2.8

Note that we can rewrite the Klein–Gordon equation (1.3) in terms of the twisted derivatives as

where the potential \({{\mathcal {V}}}\) is given by

Now, we also associate a twisted energy-momentum tensor to the twisted derivatives.

Definition 2.9

(Twisted energy-momentum tensor). Let f be smooth and nowhere vanishing and \({\tilde{\nabla }}\) as defined in Definition 2.7. We define the twisted energy-momentum tensor associated to (1.3) and f as

where \({{\mathcal {V}}}\) is as in (2.32) and \(\phi \) is any smooth function.

We will now compute the divergence of the twisted energy-momentum tensor.

Proposition 2.10

[43, Proposition 3] Let \(\phi \) be a smooth function and f be a smooth nowhere vanishing twisting function. Then,

where

Now, assume that \(\phi \) moreover satisfies (1.3) and X is a smooth vector field. Set

Then,

Finally, note that if the twisting function f associated to \({\tilde{\nabla }}\) is chosen such that \({{\mathcal {V}}}\ge 0\), then \(\tilde{{\mathbf {T}}}_{\mu \nu }\) satisfies the dominant energy condition, i.e. if X is a future pointing causal vector field, then so is \(-{\tilde{J}}^X\).

We will make use of the twisted energy-momentum tensor in the interior region \({\mathcal {B}}\) for which we use null coordinates \((u_{{\mathcal {B}}}, v_{{\mathcal {B}}})\) introduced in Sect. 2.1. For the rest of the subsection we will drop the index \({\mathcal {B}}\). Then, setting

where \(r = r(u,v)\), we write the metric in the interior region \({\mathcal {B}}\) as

Note that in the interior we have \(r_-< r(u,v) < r_+\) and \(\mathrm {d}r_*= \frac{r^2}{\Delta } \mathrm {d}r\). In Proposition A.1 in the “Appendix” we have written out the components of the twisted energy-momentum tensor, the twisted 1-jets \({\tilde{J}}^X\) and the twisted bulk term \({\tilde{K}}^X\) in null components. We will use the notation \({\mathcal {C}}_{u_1} := \{ u = u_1 \} \), \(\underline{{\mathcal {C}}}_{v_1} = \{v = v_1 \}\) for null cones and \(\Sigma _{r_1} = \{ r = r_1 \}\) for spacelike hypersurfaces in the interior. Furthermore, we set (in mild abuse of notation)

and analogously for \(\Sigma \) and \(\underline{{\mathcal {C}}}\). We will also make use of the following notation. For any \({\tilde{r}}\in (r_-,r_+)\) we set

and for hypersurfaces with constant u, v, r we denote \(n_{{{\mathcal {C}}}_u},n_{\underline{{\mathcal {C}}}_v},n_{\Sigma _r}\) as their normals.Footnote 8

Twisted red-shift vector field.

Proposition 2.11

There exist a \({r_{\mathrm {red}}}\in (r_-,r_+)\), a constant \(b(M,Q,l,\alpha )>0\), a nowhere vanishing smooth function f associated to the twisted energy momentum tensor and a future directed timelike vector field N such that

for \({\mathcal {R}}_{\mathrm {red}}:= \{ {r_{\mathrm {red}}}\le r\le r_+ \} \cap \{v \ge 1\}\) and any smooth solution \(\phi \) to (1.3).

Proof

This is proven in “Appendix A.2”. \(\quad \square \)

We will now prove the main estimate which we will use in the red-shift region in the interior.

Proposition 2.12

Let \(\phi \) be a smooth solution to (1.3) and let \(r_0 \in [{r_{\mathrm {red}}},r_+)\). Then, for any \(1\le v_1 \le v_2\) we obtain

Proof

We apply the energy identity (spacetime integral of (2.37)) in the region \({\mathcal {R}}(v_1,v_2) := \{ r_0 \le r \le r_+\} \cap \{ v_1 \le v \le v_2\}\) to obtain

Finally, the claim follows from Proposition 2.11. \(\quad \square \)

Twisted no-shift vector field. In this region we propagate estimates towards \(i^+\) from the red-shift region to the blue-shift region using a \(T=\partial _t\) invariant vector field X and a t-independent twisting function f. Take \({r_{\mathrm {red}}}\) fixed from Proposition 2.11 and let \(r_{\mathrm {blue}}>r_-\) be close to \(r_-\). We will use the no-shift vector field in two different parts of the paper: First, we will use it in the proof of Proposition A.2 in the “Appendix” in order to prove well-definedness of the Fourier projections. In this case we will choose \(r_{\mathrm {blue}}\) in principle arbitrarily close to \(r_-\). The estimate degenerates as we take \(r_{\mathrm {blue}}\rightarrow r_-\), however for the purpose of Proposition A.2 such an estimate is sufficient. Our second application of the no-shift vector field is to propagate decay of the low-frequency part \(\psi _\flat \) in the interior (see already Sect. 4.2). Here, we will take \(r_{\mathrm {blue}}= r_{\mathrm {blue}}(M,Q,l)\) only depending on the black hole parameters as determined in Proposition 4.16.

In either case, we will choose

as our vector field. (Indeed, any future directed and T invariant vector field would work.) We define our twisting function as

for some \(\beta _{\mathrm {ns}} = \beta _{\mathrm {ns}}(r_{\mathrm {blue}}) >0\) large enough such that

uniformly in \([r_{\mathrm {blue}},{r_{\mathrm {red}}}]\). In particular, since \(r\in [r_{\mathrm {blue}},{r_{\mathrm {red}}}]\) is bounded away from \(r_+,r_-\), we have

for a smooth function \(\phi \). Our main estimate in the no-shift region is

Proposition 2.13

Let \(\phi \) be a smooth solution to (1.3) and \(r_0 \in [r_{\mathrm {blue}}, {r_{\mathrm {red}}}]\). Then for any \(v_*\ge 1 \) we have

where we remark that \(v_*- v_{{r_{\mathrm {red}}}}(u_{r_0}(v_*))) = const.\)

Proof

We apply the energy identity (spacetime integral of (2.37)) with \(X = \partial _u + \partial _v\) (cf. (2.45)) and \(f_{\mathrm {ns}}\) as in (2.46) in the region \(\{ r_0 \le r\le {r_{\mathrm {red}}}\} \cap \{u < u_{r_{\mathrm {blue}}}(v_*)\}\cap \{ v \le 2v_*\}\). The choice of \(f_{\mathrm {ns}}\) guarantees the twisted dominated energy condition for the twisted energy-momentum tensor. Together with the coarea formula as well as the facts that \([r_*(r_0),r_*({r_{\mathrm {red}}})]\) is compact and X is T invariant, we conclude

for a constant \(B_1 = B_1(M,Q,l,\alpha ,\Sigma _0,{r_{\mathrm {red}}},r_{\mathrm {blue}})\). Similarly, after setting

for \({\tilde{r}}\in [r_0,{r_{\mathrm {red}}}]\), we also have

for a constant \({\tilde{B}}_1 = {\tilde{B}}_1 (M,Q,l,\alpha ,\Sigma _0)\). An application of Grönwall’s inequality yields

which implies the result. \(\quad \square \)

We will use an additional vector field in the interior in the blue-shift region \((r_-, r_{\mathrm {blue}}]\). We will however only define it later in the paper in Sect. 4.2.3 when we actually use it to propagate estimates for the low-frequency part \(\psi _\flat \) all the way to the Cauchy horizon.

Notation

In the main part of the paper we will makes use of the Fourier transform and convolution associated to the coordinate t in \((t,r,\theta ,\varphi )\) coordinates as in (2.4). We denote \({\mathcal {F}}_T\) as the Fourier transform (and \({\mathcal {F}}_T^{-1}\) as its inverse) defined as

in the coordinates \((t,r,\varphi ,\theta )\) of \({\mathcal {R}}_A, {\mathcal {R}}_B\) and \({\mathcal {B}}\), respectively. Here, we assume that \(t\mapsto f(t,r,\theta ,\varphi )\) is (at least) a tempered distribution and (2.54), in general, is to be understood in the distributional sense. Moreover, the convolution \(*\) associated to the coordinate t is defined as

where we again assume that \(t\mapsto f(t,r,\theta ,\varphi )\) is a tempered distribution and \(t\mapsto g(t,r,\theta ,\varphi )\) is a Schwartz function. Here, (2.55), in general, is to be understood in the distributional sense.

3 Main Theorem and Frequency Decomposition

Now, we are in the position to state our main result

Theorem 3.1

Let the Reissner–Nordström–AdS parameters (M, Q, l) and the Klein–Gordon mass \(\alpha < \frac{9}{4}\) be as in (2.3). Let \(\psi \in C^\infty ({\mathcal {M}}_\mathrm {RNAdS} {\setminus } \mathcal {CH})\) be a solution to (1.3) arising from smooth and compactly supported initial data \((\psi ,{\mathcal {T}} \psi )\upharpoonright _{\Sigma _0} = (\psi _0,\psi _1) \in C_c^\infty (\Sigma _0) \times C_c^\infty (\Sigma _0)\) on \(\Sigma _0\) with Dirichlet (reflecting) boundary conditions imposed at \({\mathcal {I}}_A\) and \({\mathcal {I}}_B\) (cf. Proposition 2.1). Then, \(\psi \) is uniformly bounded in the interior region \({\mathcal {B}}\) satisfying

where \(D[\psi ]\) is defined as

Moreover, \(\psi \) extends continuously to the Cauchy horizon, i.e. \(\psi \in C^0({\mathcal {M}}_{\mathrm {RNAdS}})\).

Remark 3.2

The data term \(D[\psi ]\) in (3.2) can be controlled by the initial data \((\psi _0,\psi _1)\) such that (3.1) can be written in terms of initial data as

for a constant \(C(M,Q,l,\alpha ,\Sigma _0)\) only depending on the parameters \(M,Q,l,\alpha \) and the choice of initial hypersurface \(\Sigma _0\).

Remark 3.3

Theorem 3.1 can be extended to a more general class of initial data using standard density arguments. In the context of uniform boundedness and continuity at the Cauchy horizon, it is enough to consider smooth and localized initial data. Nevertheless, note that for more general initial data in appropriate Sobolev spaces, already well-posedness becomes more delicate [39].

Proof of Theorem 3.1

We split up the proof in four steps, where Step 3 and Step 4 are the main parts relying on Sects. 4 and 5.

Step 1: Decomposition into low and high frequencies Let

be as in the assumption of Theorem 3.1. Now, in \({\mathcal {R}}_A\), \({\mathcal {R}}_B\) and in \({\mathcal {B}}\), define the low frequency part \(\psi _\flat \) and the high frequency part \(\psi _\sharp \) as

where

From Proposition A.3 in the “Appendix” we know that the low and high frequency parts \(\psi _\flat \) and \(\psi _\sharp \) in (3.5) are well-defined and \(\psi _\flat \) and \(\psi _\sharp \) extend to smooth solutions of (1.3) on \({\mathcal {M}}_{\mathrm {RNAdS}} {\setminus } \mathcal {CH}\). The cut-off frequency \(\omega _0 = \omega _0(M,Q,l,\alpha )>0\) will be chosen in the proof of Proposition 4.5 only depending on \(M,Q,l,\alpha \). For convenience we can also assume that \(\chi _{\omega _0}\) is a symmetric function which implies that \(\psi _\flat \) and \(\psi _\sharp \) will be real-valued as long as \(\psi \) was real valued. This concludes Step 1.

Having decomposed the solution in low and high frequency parts \(\psi _\flat \) and \(\psi _\sharp \), we shall now see how the initial data \(D[\psi _\flat ]\) and \(D[\psi _\sharp ]\), respectively, can be bounded by the initial data \(D[\psi ]\) of \(\psi \).

Step 2: Estimating the initial data of the decomposed solution This step is the content of the following proposition.

Proposition 3.4

Let \(\psi \) be as in (3.4) and \(\psi _\flat ,\psi _\sharp \) be as in (3.5) and recall the definition of \(D[\cdot ]\) from (3.2). Then,

Proof

Since \(\psi = \psi _\flat + \psi _\sharp \), it suffices to obtain a bound of the type \(D[\psi _\flat ] \lesssim D[\psi ]\), where \(D[\cdot ]\) is defined in (3.2). Because of the Dirichlet conditions imposed at infinity, the energy fluxes through \({\mathcal {I}}_A\) and \({\mathcal {I}}_B\) vanish [see (2.21)], and we estimate

where \(\tilde{D}[\psi _\flat ]\) is a higher order energy on the hypersurface

to be made precise in the following. Note also that the normal vector field on \({\mathcal {R}}_A\cap {\tilde{\Sigma }}_0\) is \(n_{\tilde{\Sigma }_0} = \frac{r}{\sqrt{\Delta }}\partial _t\).

More precisely, due to the support properties of the initial data, there exists a relatively compact 3-dimensional spherically symmetric submanifold \(K \subset \tilde{\Sigma }_0\) with \({\mathcal {B}}_-\subset K\)Footnote 9 and such that

Estimate (3.8) follows from general theory [18], that is a (higher order) energy estimate followed by an application of Grönwall’s lemma. In order to estimate the energy on the compact hypersurface K we decompose K in \(K\cap {\mathcal {R}}_A \) and \(K \cap {\mathcal {R}}_B\) and estimate the energy on each of those slices independently. Again, in view of the fact that \({\mathcal {R}}_A\) and \({\mathcal {R}}_B\) can be treated analogously, we only show the estimate in \({\mathcal {R}}_A\). Note that all the terms of

are of the form

for appropriate T invariant weight functions \(f\ge 0\) and T invariant coordinate derivatives \(\partial \in \{ \partial _t, \partial _r , \partial _\theta ,\partial _\varphi \}\) of order \(k=0,1,2,3\). Using that

where \( {\mathcal {F}}_T^{-1} \left[ {\chi _{\omega _0}}\right] =: \eta \) is a fixed Schwartz function, we conclude—again since T is Killing—that

where we have used boundedness of higher order energies in the exterior which are proved in [38, 40] and restated in Proposition 2.4. Also note that we can interchange the derivatives with the convolution since T is a Killing vector field. Thus, we conclude that \({\tilde{D}}[\psi _\flat ] \lesssim {\tilde{D}}[\psi ]\) and again by Cauchy stability and the vanishing of the energy flux at \({\mathcal {I}}\) [see (2.21)], we can bound \( {\tilde{D}}[\psi ] \lesssim D[\psi ]\) which finally shows \(D[\psi _\flat ] \lesssim D[\psi ]\). Hence, \(D[\psi _\sharp ] \lesssim D[\psi ]\) also holds true. \(\quad \square \)

The previous analysis in Step 1 and Step 2 allows us to treat the low and high frequency parts \(\psi _\flat \) and \(\psi _\sharp \) completely independently.

Step 3: Uniform boundedness for\(\psi _\flat \)and\(\psi _\sharp \) This step is at the heart of the paper and will be proved in Sects. 4 and 5. According to Propositions 4.17 and 5.3,

and

Thus, in view of Step 2, we conclude

which shows (3.1).

Step 4: Continuous extendibility beyond the Cauchy horizon Again, this is proved Sects. 4 and 5. In particular, in Propositions 4.18 and 5.4 it is proved that \(\psi _\flat \) and \(\psi _\sharp \), respectively, are continuously extendible beyond the Cauchy horizon. Thus, \(\psi = \psi _\flat + \psi _\sharp \) can be continuously extended beyond the Cauchy horizon which concludes the proof. \(\quad \square \)

4 Low Frequency Part \(\psi _\flat \)

We will begin this section by showing that \(\psi _\flat \) decays superpolynomially in the exterior regions \({\mathcal {R}}_A\) and \({\mathcal {R}}_B\) (Sect. 4.1). This strong decay in the exterior regions then leads to uniform boundedness of \(\psi _\flat \) in the interior \({\mathcal {B}}\) and continuous extendibility of \(\psi _\flat \) beyond the Cauchy horizon. This will be shown in Sect. 4.2. In the following, it suffices to only consider \({\mathcal {R}}_A\) because the region \({\mathcal {R}}_B\) can be treated completely analogously.

4.1 Exterior estimates

We will now consider \(\psi _\flat \) in the exterior region \({\mathcal {R}}_A\) and show an integrated energy decay estimate which will eventually lead to the superpolynomial decay for \(\psi _\flat \). First, however, we review the separation of variables for solutions to (1.3).

Definition 4.1

Let \(\phi \in CH_{\mathrm {RNAdS}}^2\) be a solution to (1.3) satisfying

for \(r\in (r_-,r_+)\), \(r\in (r_+,\infty )\) and every \(|m|\le \ell \). In the regions \({\mathcal {B}}\) and \({\mathcal {R}}_A\), respectively, set

where \((Y_{\ell m})_{|m|\le \ell }\) are the standard spherical harmonics.

Proposition 4.2

Let \(\psi \) be as in (3.4) and \(\psi _\flat \), \(\psi _\sharp \) be as in (3.5). Then, \(u[\psi ](r,\omega ,\ell ,m)\), \(u[\psi _\flat ](r,\omega ,\ell ,m)\) and \(u[\psi _\sharp ](r,\omega ,\ell ,m)\) as in Definition 4.1 are well-defined and smooth functions of \(r,\omega \) in \({\mathcal {R}}_A\) and \({\mathcal {B}}\).

Proof

First, note that \(\psi ^{\ell m} := \langle \psi , Y_{\ell m}\rangle Y_{\ell m}\) is a solution to (1.3), supported on the fixed angular parameter tuple \((\ell ,m)\). Thus, in view of Propositions 2.4 and A.4, \(\psi ^{\ell m}(t,r,\theta ,\varphi )\) and all its derivatives decay exponentially in t in \({\mathcal {R}}_A\) and in \({\mathcal {B}}\) on any \(\{ r=const. \}\) slice. \(\quad \square \)

Proposition 4.3

Let \(\phi \in CH_{\mathrm {RNAdS}}^2\) be a \(C^2\)-solution to (1.3) satisfying (4.1). Let \(u[\phi ]\) be defined as in (4.2). Then, \(u[\phi ]\) solves the radial o.d.e. (in \({\mathcal {B}}\) and \({\mathcal {R}}_A\))

where \({}^\prime = \frac{\mathrm {d}}{\mathrm {d}r_*}\),

and

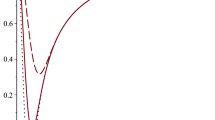

Moreover, in the exterior region \({\mathcal {R}}_A\) we have \(\lim _{r\rightarrow \infty } |r^{\frac{1}{2}} u[\phi ]| = 0\), \( \lim _{r\rightarrow \infty } |r^{- \frac{1}{2}} u[\phi ]^\prime |= 0\). Finally, note that

Proof

The fact that \(u[\phi ]\) solves the radial o.d.e. is a direct computation. For the decay statement as \(r\rightarrow \infty \), note that \(u[\phi ](r,\omega , \ell ,m) = u[\phi _{\ell m}](r,\omega ,\ell ,m)\), where \(\phi _{\ell m}:= \langle \phi , Y_{\ell m}\rangle _{\mathbb S^2} Y_{\ell m}\). In particular, (2.28) (together with Remark 2.5) then implies \(\int _{-\infty }^{\infty } \left( \int _{r_+}^\infty r^2 |\langle \phi , Y_{\ell m}\rangle _{{\mathbb {S}}^2}|^2 \mathrm {d}r\right) ^{\frac{1}{2}} \mathrm {d}t <\infty .\) Thus,

Since \(u[\phi ]\) solves (4.3), analyzing the indicial equation at the regular singularity \(r=\infty \) (see [24, Section 2.2.2]), shows that \( | r^{\frac{1}{2}} u[\phi ]| = O(r^{-\sqrt{\frac{9}{4} - \alpha }}) \) and \( |r^{-\frac{1}{2}} u[\phi ]^\prime |= O(r^{-\sqrt{\frac{9}{4} - \alpha }}) \) as \(r\rightarrow \infty \) in order to satisfy (4.7).Footnote 10\(\quad \square \)

Next, we prove that the potential \(V_\ell \) has a local maximum for large enough angular parameter \(\ell _0\).

Proposition 4.4

There exists an \({\tilde{\ell }}_0(M,Q,l,\alpha ) \in {\mathbb {N}}\) such that for all \(\ell \ge {\tilde{\ell }}_0\), the potential \(V_\ell \) has a local maximum \( r_{\ell ,\mathrm {max}} > r_+\) and \(V^\prime _\ell \ge 0\) for \(r_+\le r \le r_{\ell ,\mathrm {max}}\). Moreover, \(r_{\ell ,\mathrm {max}} \rightarrow r_{\mathrm {max}}:=\frac{3}{2}M + \sqrt{\frac{9}{4}M^2 - 2 Q^2}\) as \(\ell \rightarrow \infty \).

Proof

Note that for \(\ell \) large enough, \(V_\ell \) is non-negative in a neighborhood of \(r_+\) with \(r\ge r_+\). Also, \(V_\ell \) vanishes at \(r=r_+\). Hence, it suffices to show that \(\frac{\mathrm {d}V_\ell }{\mathrm {d}r} \) is negative somewhere for \(r\ge r_+\). But note that

for some function F(r) which is independent of \(\ell \). Now, first choose \(r>r_+\) large enough only depending on M, Q such that the last term is negative. Then, choose \(\ell \) large enough such that it dominates the first term which proves that a \(r_{\ell ,\mathrm {max}}\) as in the statement exists. The limiting behavior \(r_{\ell ,\mathrm {max}} \rightarrow \frac{3}{2}M + \sqrt{\frac{9}{4}M^2 - 2 Q^2}\) as \(\ell \rightarrow \infty \) also follows from (4.8). This concludes the proof. \(\quad \square \)

Now, we are in the position to prove a frequency localized integrated decay estimate in the exterior region for the bounded frequencies \(|\omega |\le 2 \omega _0\).

Proposition 4.5

Let \(u(r_*) = u^{(\omega ,m,\ell )} (r_*)\) solve the radial o.d.e. (4.3) in the exterior \({\mathcal {R}}_A\) and assume that \(\lim _{r\rightarrow \infty } |r^{\frac{1}{2}} u | = 0 \) and \(\lim _{r\rightarrow \infty } |r^{-\frac{1}{2}} u^\prime |= 0\). Moreover, let \(|\omega | \le 2 \omega _0\), where \(\omega _0(M,Q,\ell ,\alpha )>0\) small enough will be fixed in the following proof. Then, we have

for all \(R_*^{-\infty }\) small enough such that \(r (R_*^{-\infty }) < r_0\), where \( r_0= r_0 (M,Q,l,\alpha )> r_+\) is determined in the following proof. Here, the boundary term \(\tilde{Q}(R_*^{-\infty })\) satisfies

Proof

We will first argue that it suffices to prove (4.9) for \(\ell \ge \ell _0(M,Q,l,\alpha ) \) for some fixed \(\ell _0(M,Q,l,\alpha ) \in {\mathbb {N}}_0\). Note that (4.9) for \(\ell \le \ell _0\) is an easier variant of [40, Proposition 7.4]. Indeed, we perform the same steps in [40, Lemma 7.3 and Proposition 7.4] but instead take \(a=0\), \(\omega _+ =0\) and \(H=0\) throughout [40, Section 7]. This leads to [40, Proposition 7.4] with L replaced by \(\ell _0\). The estimate on the boundary term follows from [40, Section 9.3].

We will now consider \(\ell \ge \ell _0\), where \(\ell _0\) is determined below. Let \(r_0, r_1\) depending only on \(M,Q,l,\alpha \) be such that \(r_+< r_0< r_1 < r_\text {max}- \delta \), where \(r_{\text {max}}\) is defined in Proposition 4.4. Here, \(\delta = \delta (\ell _0)>0\) is such that \(V^\prime \ge 0\) for all \(r_+\le r \le r_\text {max} - \delta \), cf. Proposition 4.4. We can make \(\delta (\ell _0)\) as small as we want by choosing \(\ell _0\) sufficiently large. Now, we choose \(\omega _0(M,Q,l,\alpha )>0\) small enough and \(\ell _0\) large enough such that

and for all \(|\omega |\le 2 \omega _0\), \(\ell \ge \ell _0\). For smooth \(f(r_*)\) and \({\tilde{h}}(r_*)\), we define the currents

with

where we recall that \(~^\prime \) denotes the derivative \(\frac{\mathrm {d}}{\mathrm {d}r_*}\). Thus,

We choose a smooth \(f\le 0\) such that

f is monotonically increasing,

\(f = - 1/r^2\) in a neighborhood of \(r=r_+\),

\(f\le -c_1\) for \(r_+\le r \le r_1\) and some \(c_1(M,Q,l)>0\),

\(\Delta \lesssim f^\prime \lesssim \Delta \) for \(r_+\le r \le r_1\),

\(|f^{\prime \prime \prime }|\lesssim \Delta \),

\(f=0\) for \(r\ge r_\text {max}-\delta \)

and a smooth \( {\tilde{h}}\ge 0\) such that

\( {\tilde{h}} =0 \) for \(r \le r_0\),

\(|{\tilde{h}}^{\prime \prime }|\lesssim 1\) for \(r_0<r_1\),

\({\tilde{h}}=1\) for \(r \ge r_1\).

Then, we have

Thus, choosing \(\ell _0(M,Q,l,\alpha )\) large enough (and \(\omega _0(M,Q,l,\alpha ) >0 \) possibly smaller) and using (4.16), (4.11), (4.8) and the properties of f and \({\tilde{h}}\), we have

for \(r_+ \le r \le r_{\text {max}} - \delta \) and

for \(r \ge r_{\text {max}} - \delta \) and some \(\tilde{c}(M,Q,l,\alpha )>0\). Integrating \({Q^f}^\prime + {Q^{\tilde{h}}}^\prime \) in the region \(r_*\in (R_*^{-\infty }, r_*(r=+\infty ) )\) and applying the following Hardy inequality (see [40, Lemma 7.1])

to control the negative signed term in (4.18), yields

Note that we use \(\lim _{r\rightarrow \infty } |r^{\frac{1}{2}} u |= 0 \) and \(\lim _{r\rightarrow \infty } |r^{- \frac{1}{2}} u^\prime | =0\) to apply the Hardy inequality. To obtain control of \(|u^\prime |^2\) in the region \(r\ge r_{\text {max}} - \delta \) in (4.20) we just add a small portion of the integral over (4.18). This proves

where \(|Q^f(R_*^{-\infty })| \lesssim ( |\omega |^2 |u|^2 + |u'|^2) (1 + O_\ell (r-r_+)\) as \(R_*^{-\infty } \rightarrow -\infty \) is satisfied by the construction of f. \(\quad \square \)

With the frequency localized integrated energy decay estimate of Proposition 4.5 we will now prove a local integrated energy decay estimate in physical space. Indeed, a naive application of Plancherel’s theorem to (4.9) gives a global integrated energy estimate. However, localizing this energy decay requires some sort of cut-off which does not respect the compact frequency support. Nevertheless, by carefully choosing a localization, we can show that the error term decays superpolynomially in time. At this point we shall remark that we do expect \(\psi _\flat \) to decay exponentially. However, for our problem, superpolynomial decay in the exterior is (more than) sufficient.

Proposition 4.6

Let \({{\psi }_\flat }\) be as in (3.5). Then, for any \(q>1\), \( \tau _1 \ge 0 \) and in view of (2.23), we have the integrated energy decay estimate

where \(C(q)>0\) is a constant only depending on q. Moreover, for any \(\tau _2 \ge 2\tau _1\), this directly implies

for the T-energy.

Proof

In order to show (4.22) we will first construct an auxiliary solution \(\Psi \) of (1.3). We set initial data for \(\Psi \) on \(\Sigma _{ \tau _1}\) as \((\Psi _0,\Psi _1) := (\psi _\flat , {\mathcal {T}}\psi _\flat )\upharpoonright _ {\Sigma _{ \tau _1} \cap {\mathcal {R}}_A}\). Then, we will define data \(\Psi _2\) on \({\mathcal {H}}_A^+ \cap \{ t^*\le \tau _1\}\) such that the data can be extended to a \(C^k\) function in a neighborhood of \({\mathcal {H}}_A^+ \cap \{t^*= \tau _1\}\) for some finite regularity k. Choosing the regularity k large enough will guarantee well-posedness. More precisely, in local coordinates \((t^*,r,\theta ,\varphi )\) and for \(r= r_+\), we define

for \(t^*\le \tau _1\) and some uniquely determined \((\lambda _j)_{1\le j \le k}\) such that

is \(C^k\). Indeed, the function is smooth everywhere except at \(t^*= \tau _1\).

In the darker shaded region \(J^+(\Sigma _{\tau _1})\cap {\mathcal {R}}_A\) we have that \(\Psi = \psi _\flat \) and in the lighter shaded region we can estimate the energy of \(\Psi \) in terms of \(\psi _\flat \). This holds true as \(\Psi _2\) is the \(C^k\) reflection of \(\psi _\flat \) from \({\mathcal {H}}_A^+ \cap \{ t^*\ge \tau _1\}\) to \({\mathcal {H}}_A^+ \cap \{ t^*< \tau _1\}\)

Now, we consider the mixed boundary value-Cauchy-characteristic problem, where we impose data as follows. On the null hypersurface \({\mathcal {H}}_A^+ \cap \{ t^*\le \tau _1 \}\) we impose \(\Psi _2\). This null cone intersects the spacelike hypersurface \(\Sigma _{ \tau _1}\) on which we have prescribed \((\Psi _0,\Psi _1)\) as data. As before, we assume the Dirichlet condition on \({\mathcal {I}}_A\). For fixed \(k >0\) large enough, this is a well-posed problem and can be solved backwards and forwards in \({\mathcal {R}}_A\) [33, Theorem 2]. We will call the arising solution \(\Psi \) and by uniqueness note that \(\Psi = \psi _\flat \) on \( ( {\mathcal {R}}_A\cup {\mathcal {H}}_A^+ ) \cap J^+(\Sigma _{ \tau _1})\). Indeed, analogously to \(\psi _\flat \), we have \(\Psi \in CH^2_{\mathrm {RNAdS}}\) and by choosing k large enough, we can make \(\Psi \) arbitrarily regular, in particular \(C^2\). Moreover, \(\Psi \) decays logarithmically and \(\langle \Psi ,Y_{\ell m}\rangle Y_{\ell m}\) decays exponentially towards \(i^+\) and \(i^-\) on a \(\{ r =const.\}\) hypersurface.Footnote 11 Refer to Fig. 5 for a visualization of the Cauchy-characteristic problem with Dirichlet boundary conditions.

Analogously to \(\psi = \psi _\flat + \psi _\sharp \), we decompose the new solution \(\Psi \) in low and high frequencies \(\Psi = \Psi _\flat + \Psi _\sharp \): We define

where \(\chi _{2\omega _0}\) is a smooth cutoff function such that \(\chi _{2\omega _0} = 1\) for \(|\omega | \le \omega _0\) and \(\chi _{2\omega _0} = 0\) for \(|\omega |\ge 2 \omega _0\). Now, note that from the T-energy identity (2.21) we have

as the flux through \({\mathcal {I}}_A\) vanishes in view of the Dirichlet boundary condition at \({\mathcal {I}}_A\). Here, we use the notation \({\mathcal {H}}_A^+ ( a, b ) := {\mathcal {H}}_A^+ \cap \{a< t^*< b \}\). Moreover, from the T energy identity, we have

We have used the estimate

which follows from our construction of the initial data. Thus,

Now, note that \(u[\Psi _\flat ]\) defined as

satisfies the assumptions of Proposition 4.5 such that (4.9) holds true for \(u[\Psi _\flat ]\). We now integrate the frequency localized energy estimate (4.9) associated to \( u[\Psi _\flat ]\) in \(\omega \) and sum over all spherical harmonics. There are two main terms appearing and we will estimate them in the following. This step is similar to [40, Sections 9.1 and 9.3] so we will be rather brief. An application of Plancherel’s theorem for the integrated left hand side of (4.9) yields

To estimate the boundary term on the right hand side of (4.9), we first decompose \(u[\Psi _\flat ]\) as \(u[\Psi _\flat ] = a(\omega ,m,\ell ) u_1 + b(\omega ,m,\ell ) u_2\), where \(u_1, u_2\) are defined as the unique solutions to the radial o.d.e. (4.3) in the exterior satisfying \(u_1 = e^{i\omega r_*} + O_\ell (r-r_+)\) and \(u_2 = e^{-i \omega r_*} + O_\ell (r-r_+)\) as \(r\rightarrow r_+\) (\(r_*\rightarrow -\infty \)). Here, \(a = a(\omega ,\ell , m)\) and \(b = b (\omega ,\ell , m)\) are the unique coefficients of the decomposition. Then, in view of (4.10) and \(u_1^\prime = i \omega u_1 + O_\ell (r-r_+)\), \(u_2^\prime = -i \omega u_2 + O_\ell (r-r_+)\), we estimate

as \(r\rightarrow r_+\). Now, using that \(\omega a(\omega )\), \(\omega b(\omega )\) are in \(L_\omega ^1({\mathbb {R}})\) and in \(L_\omega ^2(\mathbb R)\) (note that they have compact support), an application of the Riemann–Lebesgue Lemma, the Fourier inversion theorem and Plancherel’s theorem shows that \(\sum _{m \ell } \int _{{\mathbb {R}}} |\omega |^2 (|a(\omega ,\ell ,m)|^2 + |b(\omega ,\ell ,m)|^2 ) \mathrm {d}\omega \lesssim \int _{{\mathcal {H}}_A^+} |T\Psi _\flat |^2 + \int _{{\mathcal {H}}_A^-} |T\Psi _\flat |^2 \le 2\int _{{\mathcal {H}}_A^+} |T\Psi _\flat |^2 \), where the last inequality follows from the T energy identity \(\int _{{\mathcal {H}}_A^+} |T\Psi _\flat |^2 = \int _{{\mathcal {H}}_A^-} |T\Psi _\flat |^2 \) in the region \({\mathcal {R}}_A\). Thus, we conclude the global integrated energy decay statement

Hence, in view of \(\psi _\flat = \Psi \) in \(\{ t^*\ge \tau _1\}\cap {\mathcal {R}}_A\) we have

Here, we have also used (4.33), (2.23) and the fact that \(\int _{{\mathcal {H}}^+_A}|T{\Psi }_\flat |^2 \lesssim \int _{{\mathcal {H}}^+_A}|T{\Psi }|^2 \). Moreover, the estimate \(\int _{{\mathcal {H}}^+_A}|T{\Psi }|^2 \lesssim \int _{\Sigma _{ \tau _1}\cap {\mathcal {R}}_A} J^T_\mu [\Psi ] n^\mu _{\Sigma _{ \tau _1}} \mathrm {dvol}_{\Sigma _{ \tau _1}}\) follows from (4.29).

Finally, we are left with the term \(\int _{t^*\ge 2\tau _1} \int _{\Sigma _{t^*}\cap {\mathcal {R}}_A} J^T_\mu [\Psi _\sharp ] n_{\Sigma _{t^*}}^\mu \mathrm {dvol}_{\Sigma _{t^*}} \mathrm {d}t^*\). We will show that this term decays at a superpolynomial rate. First, introduce the notation \(\chi _\sharp := 1 - \chi _{2\omega _0}\) and set \(\check{\chi _{2\omega _0}}:= {\mathcal {F}}^{-1}_T(\chi _{2\omega _0})\), \(\check{\chi _\sharp }:= {\mathcal {F}}^{-1}_T (\chi _\sharp )\), which are well-defined in the distributional sense. Then,

since \(\check{\chi }_\sharp *\psi _\flat =0\) in view of their disjoint Fourier support. In particular, for \(t^*\ge \tau _1\) we have

as \(\delta *(\Psi -\psi _\flat ) = \Psi -\psi _\flat =0\) for \(t^*\ge \tau _1\). To make notation easier we define \(\phi := -\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi }} (\Psi -\psi _\flat )\) which is only supported for \(t^*\le \tau _1\) and satisfies \(\Psi _\sharp = \check{\chi _{2\omega _0}} *\phi \). Now, as a result of the T invariance of \(\mathrm {dvol}_{\Sigma _{t^*}}\) and \(J_\mu ^T[\cdot ]n^\mu _{\Sigma _{t^*}}\), as well as (2.23), we have that

Here, we have used the boundedness of the T-energy (cf. (2.22)), i.e.

Finally, we have also used that the Schwartz function \(\check{\chi _{2\omega _0}}\) decays superpolynomially at any power \(q>1\). This concludes the proof in view of (4.34). \(\quad \square \)

In order to remove the degeneracy of the T-energy at the event horizon, we will use the by now standard red-shift vector field [18]. As usual, the red-shift vector field N is a future-directed T invariant timelike vector field which has a positive bulk term \(K^N\ge 0\) near the event horizon. In a compact r region bounded away from the event horizon \({\mathcal {H}}_A^+\), the bulk term \(K^N\) of N is sign-indefinite but this will be absorbed in the spacetime integral of the T current in Proposition 4.6. Also, note that \(N=T\) for large enough r. In the negative mass AdS setting, we refer to [38, Section 4.2] for an explicit construction of the red-shift vector field N. Note that the red-shift vector field N has the property that

for \(\psi _\flat \) as in (3.5).

Proposition 4.7

Let \({{\psi }_\flat }\) be as in (3.5). Then for any \(\tau _2 \ge 2\tau _1 \ge 0\), we have

and in particular,

Proof

We apply the energy identity (the spacetime integral of (2.19)) with the red-shift vector field N for \({{\psi }_\flat }\) in the region \({\mathcal {R}}_A\cap \{ 2\tau _1\le t^*\le \tau _2 \}\), where \(2{\tau _1}\le \tau _2\). After taking care of the negative lower order term via a Hardy inequality and absorbing the sign-indefinite bulk of N away from the horizon (in the region \(\{r\ge r_0\}\) for some \(r_0 > r_+\)) in the spacetime integral of \(J^T\) on the right hand side (see [38, Section 4] for further details), we arrive at

First, note that the integrated energy term \(\int _{2\tau _1}^{\tau _2} \int _{\Sigma _{t^*}\cap {\mathcal {R}}_A \cap \{ r\ge r_0 \} } J_\mu ^T[ {{\psi }_\flat }] n^\mu _{\Sigma _{t^*}} \mathrm {dvol}_{\Sigma _{t^*}} \mathrm {d}t^*\) on the right-hand side of (4.41) can be controlled by the left-hand side of Proposition 4.6. Then, remark that the integral along the horizon \(\int _{{\mathcal {H}}^+_A\cap \{2\tau _1\le t^*\le \tau _2\}}J^N_\mu [{{\psi }_\flat }]n^\mu _{{\mathcal {H}}} \mathrm {dvol}_{{\mathcal {H}}}\) is sign-indefinite due to the (possible) negative mass. However, this can be absorbed in the bulk term using an \(\epsilon \) of the integrated bulk term of the red-shift vector field N and some of the bulk term of the integrated energy estimate in Proposition 4.6, cf. [38, Equation (70)]. Finally, using the integrated energy estimate from Proposition 4.6 again, we conclude

\(\square \)

Now we obtain

Proposition 4.8

Let \(\psi _\flat \) be defined as in (3.5). Then, for any \(q>1\) and \(\tau \ge 0\) we have

and

Proof

In view of Theorem 4.7 it suffices to prove (4.43). Upon setting

we have from Proposition 4.7 that

for any \(t_2\ge 2 t_1 \ge 0\). The claim follows now from Lemma 4.9 below. \(\quad \square \)

Lemma 4.9

Let \(f:[0,\infty )\rightarrow [0,\infty )\) be a continuous function satisfying

for any \(q>1\), \(0\le 2t_1 \le t_2\) and some \(\alpha (q) >0\) only depending on q. Then, for all \(q>1\), there exists a constant \(C(\alpha (q),q)>0\) only depending on \(\alpha \) and q such that

for all \(t\ge 0\).

Proof

Fix \(q>1\). First, note that from (4.45) we have for any \(t_2\ge 2 t_1>0\)

Without loss of generality, let \(t>10\) be arbitrary. Then, take a dyadic sequence \(\tau _{k+1} = 2\tau _k\), where \(\tau _0 =1\). Now, there exists a \(n\in {\mathbb {N}}_0\) such that \(t\in [\tau _{n+3} , \tau _{n+4}]\). Then, again from (4.45) we have

from which we conclude that there exists a \(\xi \in [\tau _{n+1}, \tau _{n+2}]\) such that

Hence, since \(2\xi \le \tau _{n+3} \le t \le \tau _{n+4}\),

Now, note that \(\tau _n \sim t\) and hence, \(f(t) \le C(1,\alpha (q)) \frac{1}{1+t}\). This improved decay can now be fed into (4.47) to obtain a decay of the form \(f(t) \le C(2,\alpha (q)) \frac{1}{1+t^2}\). This procedure can be iterated until one obtains

\(\square \)

4.2 Interior estimates

Having obtained the superpolynomial decay for \(\psi _\flat \) in the exterior and in particular on the event horizon, we will now use this to show uniform boundedness in the black hole interior. We will first propagate the superpolynomial decay on the horizon established in Proposition 4.8 further into the interior. To do so we will make use of the twisted red-shift.

4.2.1 Red-shift region.

With the help of the constructed twisted red-shift current in Proposition 2.11, we obtain

Proposition 4.10

Let \(r_0 \in [{r_{\mathrm {red}}},r_+)\). Let \({{\psi }_\flat }\) defined as in (3.5) and recall that from Proposition 4.8 we have

for \(1\le v_1 \le v_2\). Then,

for any \(1\le v_1 \le v_2\).

Proof

From Proposition 2.12, estimate (4.44) in Proposition 4.8 and upon defining

we obtain

for any \(1\le v_1 \le v_2\). This implies

for any \(v\ge 1\). This follows from an argument very similar to Lemma 4.9. Note that we have by general theory [18] that \({\tilde{E}}(v=1) \lesssim E_1[\psi _\flat ](0)\). Thus,

for \(v\ge 1\) which proves (4.50). The estimate (4.51) now follows from (4.50) and Proposition 2.12. \(\quad \square \)

4.2.2 No-shift region.

Now, we will propagate the decay towards \(i^+\) further into the black hole for \(r\in [{r_{\mathrm {red}}},r_{\mathrm {blue}}]\), where \(r_{\mathrm {blue}}>r_-\) is determined in the proof of Proposition 4.16.

Proposition 4.11

Let \({{\psi }_\flat }\) defined as in (3.5). For any \(r_0 \in [r_{\mathrm {blue}}, {r_{\mathrm {red}}}]\), \(q>1\) and any \(v_*\ge 1\) we have

Moreover, for any \(1<p<q\) we also have

Proof

Applying Proposition 2.13 with \(\phi = \psi _\flat \) we have (2.49) for \(\psi _\flat \). To estimate the right-hand side of (2.49) we use Proposition 4.10 and the fact that the difference \(v_*- v_{{r_{\mathrm {red}}}}(u_{r_0}(v_*))) = const.\) to obtain

from which (4.56) follows. Finally, (4.57) is a consequence of the fact that \( \langle v \rangle ^p \sim \langle u \rangle ^p\) (using \(r_{\mathrm {blue}}\le r \le {r_{\mathrm {red}}}\)) and the following well-known lemma. \(\quad \square \)

Lemma 4.12

Let \(f:[1,\infty ) \rightarrow {\mathbb {R}}_{\ge 0}\) be continuous and assume that there exists a \(q\in {\mathbb {R}}\), \(q>1\) such that \(\int _x^{2x} f(s) \mathrm {d}s \le \frac{D}{x^q}\) for all \(x\ge 1\) and some constant \(D>0\). Let \(1<p<q\) be fixed. Then, \(\int _1^\infty s^p f(s) \mathrm {d}s < C(q,p) D\) for a constant \(C(p,q)>0\) only depending on p and q.

Proof

Set \(x_i := 2^i \). Then, \(\int _1^\infty s^p f(s) \mathrm {d}s = \sum _{i=0}^\infty \int _{x_i}^{x_{i+1}} s^p f(s) \mathrm {d}s\le 2^p D \sum _{i=0}^\infty 2^{ip-iq}<C(q,p) D.\)\(\quad \square \)

Remark 4.13

From now on we will consider p and q as fixed and constants appearing in \(\lesssim \), \(\gtrsim \) and \(\sim \) can additionally depend on \(1<p<q\).