Abstract

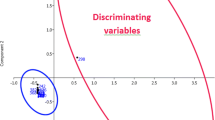

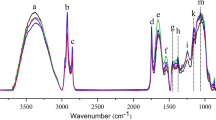

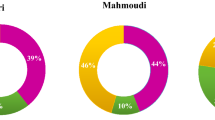

A fuzzy chromatography mass spectrometric (FCMS) fingerprinting method combined with chemometric analysis has been established for rapid discrimination of whole-grain flour (WF) from refined wheat flour (RF). Bran, germ, endosperm, and WF from three local cultivars or purchased from a grocery store were studied. The state of refinement (whole vs. refined) of wheat flour was differentiated successfully by use of principal-components analysis (PCA) and soft independent modeling of class analogy (SIMCA), despite potential confounding introduced by wheat class (red vs. white; hard vs. soft) or resources (different brands). Twelve discriminatory variables were putatively identified. Among these, dihexoside, trihexoside, apigenin glycosides, and citric acid had the highest peak intensity for germ. Variable line plots indicated phospholipids were more abundant in endosperm. Samples of RF and WF from three cultivars (Hard Red, Hard White, and Soft White) were physically mixed to furnish 20, 40, 60, and 80 % WF of each cultivar. SIMCA was able to discriminate between 100 %, 80 %, 60 %, 40 %, and 20 % WF and 100 % RF. Partial least-squares (PLS) regression was used for prediction of RF-to-WF ratios in the mixed samples. When PLS models were used the relative prediction errors for RF-to-WF ratios were less than 6 %.

Workflow of targeting discriminatory compounds by use of FCMS and chemometric analysis

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Fung TT, Hu FB, Pereira MA, Liu S, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC (2002) Whole-grain intake and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective study in men. Am J Clin Nutr 76(3):535–540

Lutsey PL, Jacobs DR, Kori S, Mayer-Davis E, Shea S, Steffen LM, Szklo M, Tracy R (2007) Whole grain intake and its cross-sectional association with obesity, insulin resistance, inflammation, diabetes and subclinical CVD: The MESA Study. Br J Nutr 98(02):397–405

Maki KC, Beiseigel JM, Jonnalagadda SS, Gugger CK, Reeves MS, Farmer MV, Kaden VN, Rains TM (2010) Whole-grain ready-to-eat oat cereal, as part of a dietary program for weight loss, reduces low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in adults with overweight and obesity more than a dietary program including low-fiber control foods. J Am Diet Assoc 110(2):205–214

Albertson A, Joshi N (2014) Whole grain consumption and associations with body weight measures in the United States: results from NHANES 2009–10 and the new USDA Food Patterns Equivalents Database (810.23). FASEB J 28(1 Supplement):810.823

McKeown NM, Meigs JB, Liu SM, Wilson PWF, Jacques PF (2002) Whole-grain intake is favorably associated with metabolic risk factors for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease in the Framingham Offspring Study. Am J Clin Nutr 76(2):390–398

Kristensen M, Toubro S, Jensen MG, Ross AB, Riboldi G, Petronio M, Bugel S, Tetens I, Astrup A (2012) Whole Grain Compared with Refined Wheat Decreases the Percentage of Body Fat Following a 12-Week, Energy-Restricted Dietary Intervention in Postmenopausal Women. J Nutr 142(4):710–716. doi:10.3945/jn.111.142315

Giacco R, Costabile G, Della Pepa G, Anniballi G, Griffo E, Mangione A, Cipriano P, Viscovo D, Clemente G, Landberg R, Pacini G, Rivellese AA, Riccardi G (2014) A whole-grain cereal-based diet lowers postprandial plasma insulin and triglyceride levels in individuals with metabolic syndrome. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 24(8):837–844. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2014.01.007

Ye EQ, Chacko SA, Chou EL, Kugizaki M, Liu SM (2012) Greater Whole-Grain Intake Is Associated with Lower Risk of Type 2 Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease, and Weight Gain. J Nutr 142(7):1304–1313. doi:10.3945/jn.111.155325

Knudsen MD, Kyrø C, Olsen A, Dragsted LO, Skeie G, Lund E, Åman P, Nilsson LM, Bueno-de-Mesquita H, Tjønneland A (2014) Self-Reported Whole-Grain Intake and Plasma Alkylresorcinol Concentrations in Combination in Relation to the Incidence of Colorectal Cancer. Am J Epidemiol. doi:10.1093/aje/kwu031

Adom KK, Liu RH (2002) Antioxidant activity of grains. J Agric Food Chem 50(21):6182–6187. doi:10.1021/Jf0205099

Aune D, Chan DSM, Lau R, Vieira R, Greenwood DC, Kampman E, Norat T (2011) Dietary fibre, whole grains, and risk of colorectal cancer: systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Br Med J 343. doi:10.1136/Bmj.D6617

Okarter N, Liu RH (2010) Health Benefits of Whole Grain Phytochemicals. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 50(3):193–208. doi:10.1080/10408390802248734

Adom KK, Sorrells ME, Liu RH (2005) Phytochemicals and antioxidant activity of milled fractions of different wheat varieties. J Agric Food Chem 53(6):2297–2306. doi:10.1021/Jf048456d

Zhao Y, Sun J, Yu LL, Chen P (2013) Chromatographic and mass spectrometric fingerprinting analyses of Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels-derived dietary supplements. Anal Bioanal Chem 405(13):4477–4485. doi:10.1007/s00216-012-6668-1

Sun JH, Chen P (2012) Chromatographic fingerprint analysis of yohimbe bark and related dietary supplements using UHPLC/UV/MS. J Pharm Biomed Anal 61:142–149. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2011.11.013

Sun J, Chen P (2011) Differentiation of Panax quinquefolius grown in the USA and China using LC/MS-based chromatographic fingerprinting and chemometric approaches. Anal Bioanal Chem 399(5):1877–1889. doi:10.1007/s00216-010-4586-7

Chen P, Sun J, Ford P (2014) Differentiation of the Four Major Species of Cinnamons (C. burmannii, C. verum, C. cassia, and C. loureiroi) Using a Flow Injection Mass Spectrometric (FIMS) Fingerprinting Method. J Agric Food Chem 62(12):2516–2521. doi:10.1021/jf405580c

Sun J, Chen P (2011) A flow-injection mass spectrometry fingerprinting method for authentication and quality assessment of Scutellaria lateriflora-based dietary supplements. Anal Bioanal Chem 401(5):1577–1584. doi:10.1007/s00216-011-5246-2

Wold S (1976) Pattern recognition by means of disjoint principal components models. Pattern Recogn 8(3):127–139. doi:10.1016/0031-3203(76)90014-5

Zhang M, Harrington PB (2015) Simultaneous quantification of Aroclor mixtures in soil samples by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry with solid phase microextraction using partial least-squares regression. Chemosphere 118:187–193. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.08.018

Dunn WJ, Stalling DL, Schwartz TR, Hogan JW, Petty JD, Johansson E, Wold S (1984) Pattern recognition for classification and determination of polychlorinated biphenyls in environmental samples. Anal Chem 56(8):1308–1313. doi:10.1021/ac00272a026

Geladi P, Kowalski BR (1986) Partial least-squares regression: a tutorial. Anal Chim Acta 185:1–17. doi:10.1016/0003-2670(86)80028-9

Moore J, Hao Z, Zhou K, Luther M, Costa J, Yu LL (2005) Carotenoid, tocopherol, phenolic acid, and antioxidant properties of Maryland-grown soft wheat. J Agric Food Chem 53(17):6649–6657. doi:10.1021/jf050481b

Kessner D, Chambers M, Burke R, Agus D, Mallick P (2008) ProteoWizard: open source software for rapid proteomics tools development. Bioinformatics 24(21):2534–2536. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btn323

Diagram of a Kernel. Montana Wheat and Barley Committee. http://wbc.agr.mt.gov/wbc/Consumer/Diagram_kernel/. Accessed 14 July 2015

Tautenhahn R, Cho K, Uritboonthai W, Zhu Z, Patti GJ, Siuzdak G (2012) An accelerated workflow for untargeted metabolomics using the METLIN database. Nat Biotechnol 30(9):826–828

Becchi M, Fraisse D (1989) Fast Atom Bombardment and Fast Atom Bombardment Collision-Activated Dissociation Mass-Analyzed Ion Kinetic-Energy Analysis of C-Glycosidic Flavonoids. Biomed Environ Mass Spectrom 18(2):122–130. doi:10.1002/bms.1200180207

Cuyckens F, Claeys M (2004) Mass spectrometry in the structural analysis of flavonoids. J Mass Spectrom 39(1):1–15. doi:10.1002/Jms.585

Li QM, Vandenheuvel H, Dillen L, Claeys M (1992) Differentiation of 6-C-Glycosidic and 8-C-Glycosidic Flavonoids by Positive-Ion Fast-Atom-Bombardment and Tandem Mass-Spectrometry. Biol Mass Spectrom 21(4):213–221. doi:10.1002/bms.1200210406

Dinelli G, Segura-Carretero A, Di Silvestro R, Marotti I, Arraez-Roman D, Benedettelli S, Ghiselli L, Fernadez-Gutierrez A (2011) Profiles of phenolic compounds in modern and old common wheat varieties determined by liquid chromatography coupled with time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A 1218(42):7670–7681. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2011.05.065

Feng X, Jiang D, Shan Y, Dai T, Dong Y, Cao W (2008) New flavonoid-C-glycosides from Triticum aestivum. Chem Nat Compd 44(2):171–173

Colborne AJ, Laidman DL (1975) The extraction and analysis of wheat phospholipids. Phytochemistry 14(12):2639–2645

Taguchi R, Houjou T, Nakanishi H, Yamazaki T, Ishida M, Imagawa M, Shimizu T (2005) Focused lipidomics by tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B 823(1):26–36

Harrison KA, Murphy RC (1995) Negative electrospray ionization of glycerophosphocholine lipids: formation of [M–15]− ions occurs via collisional decomposition of adduct anions. J Mass Spectrom 30(12):1772–1773

Ekroos K, Ejsing CS, Bahr U, Karas M, Simons K, Shevchenko A (2003) Charting molecular composition of phosphatidylcholines by fatty acid scanning and ion trap MS3 fragmentation. J Lipid Res 44(11):2181–2192

Zhang M, Harrington PB (2013) Automated pipeline for classifying Aroclors in soil by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry using modulo compressed two-way data objects. Talanta 117:483–491. doi:10.1016/j.talanta.2013.09.050

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr Reuben McClean from Pendleton Flour Mills for providing local flour samples.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

The variable line plot of the ion at m/z 769.20 (Fig. S1), MSn spectra of the ion at m/z 769.2 (Fig. S2), MS–MS spectra of the ion at m/z 564.33 (Fig. S3), MSn spectra of the ion at m/z 476.3 (Fig. S4), and PCA for all RF/WF mixtures prepared from three cultivars (Fig. S5) are presented in a supplemental file.

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(PDF 876 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Geng, P., Zhang, M., Harnly, J.M. et al. Use of fuzzy chromatography mass spectrometric (FCMS) fingerprinting and chemometric analysis for differentiation of whole-grain and refined wheat (T. aestivum) flour. Anal Bioanal Chem 407, 7875–7888 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-015-9007-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-015-9007-5