Abstract

Rationale

Drugs of abuse are initially used because of their rewarding properties. As a result of repeated drug exposure, sensitization to certain behavioral effects of drugs occurs, which may facilitate the development of addiction. Recent studies have implicated the metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGlu5 receptor) in drug reward, but its role in sensitization is unclear. Stimulation of dopamine receptors plays an important role in drug reward, but not in the sensitizing properties of cocaine and morphine.

Objective

This study aims to evaluate the role of mGlu5 and dopamine receptors in the development of cocaine- and morphine-induced conditioned place preference (CPP) and psychomotor sensitization.

Materials and methods

Rats were treated with the mGlu5 receptor antagonist MTEP (0, 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg, i.p.) or the dopamine receptor antagonist α-flupenthixol (0, 0.125, 0.25, and 0.5 mg/kg, i.p.) during place conditioning with either morphine (3 mg/kg, s.c.) or cocaine (15 mg/kg, i.p.). Furthermore, MTEP (1 mg/kg, i.p.) or α-flupenthixol (0.5 mg/kg, i.p.) was co-administered during cocaine (30 mg/kg, i.p.) or morphine (3.0 mg/kg, s.c.) pretreatment and psychomotor sensitization was tested 3 weeks post-treatment.

Results

MTEP attenuated the development of morphine- but not cocaine-induced CPP. In contrast, MTEP suppressed the development of cocaine- but not morphine-induced psychomotor sensitization. α-Flupenthixol blocked the development of both cocaine- and morphine-induced CPP but did not affect the development of sensitization to either drug.

Conclusion

Dopamine receptor stimulation mediates cocaine and morphine reward but not sensitization. In contrast, the role of mGlu5 receptors in reward and sensitization is drug-specific.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the last two decades, a substantial body of evidence implicating glutamatergic neurotransmission in the development and expression of neuroplastic changes underlying drug addiction has accumulated (Wolf 1998; Vanderschuren and Kalivas 2000; Kalivas 2009; Schmidt and Pierce 2010). Glutamate can bind to two distinct receptor types: the ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGlu receptors) and the metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGlu receptors) (Spooren et al. 2003; Kew and Kemp 2005). Most research on the role of glutamate in addictive behavior has focused on iGlu receptors, and although studies have shown that iGlu receptors are involved in drug reward and sensitization (Vanderschuren and Kalivas 2000; Wolf 1998; Gass and Olive 2008; Schmidt and Pierce 2010) clinical trials have thus far been unsuccessful in identifying iGlu receptor ligands that effectively treat addiction (Bisaga et al. 2000; Tzschentke 2002; Heidbreder and Hagan 2005).

Recent studies have identified mGlu receptors as potential targets for the treatment of drug addiction. Eight different subtypes of this receptor have been described, of which the metabotropic glutamate 5 receptor (mGlu5 receptor) has been most prominently implicated in addictive behavior (Kenny and Markou 2004; Spooren et al. 2003; Gass and Olive 2008). For instance, the mGlu5 receptor antagonist 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine (MPEP) has been shown to block the development of cocaine- and morphine-conditioned place preference (CPP) (Popik and Wrobel 2002; Herzig and Schmidt 2004; Aoki et al. 2004), although in one study the effect of MPEP on drug-induced CPP was specific for cocaine; i.e., morphine, nicotine, amphetamine, and alcohol CPP were not affected (McGeehan and Olive 2003). Furthermore, mGlu5 receptor knockout mice do not self-administer cocaine (Chiamulera et al. 2001) and MPEP or the structurally related mGlu5 receptor antagonist 3-[(2-methyl-1, 3-thiazol-4-yl) ethynyl] pyridine (MTEP) decreased self-administration of different drugs of abuse, including cocaine, metamphetamine, heroin, alcohol, nicotine, and ketamine under fixed-ratio schedules of reinforcement (Paterson et al. 2003; Tessari et al. 2004; Olive et al. 2005; Kenny et al. 2005; Schroeder et al. 2005; van der Kam et al. 2007; Gass et al. 2009; Martin-Fardon et al. 2009). In addition, MPEP and MTEP were also found to reduce breakpoints in animals responding for cocaine, methamphetamine, alcohol, and nicotine under a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement, whereas the effects on responding for food were inconsistent between studies (Paterson and Markou 2005; Besheer et al. 2008; Gass et al. 2009). Together, these studies suggest that the mGlu5 receptor is critically involved in -drug reinforcement.

The mGlu5 receptor has also been implicated in drug-induced psychomotor hyperactivity. The psychomotor stimulant effect of cocaine is absent in mGlu5 receptor knockout mice (Chiamulera et al. 2001) and MPEP decreases the acute psychomotor effects of cocaine, amphetamine, and nicotine (McGeehan et al. 2004; Herzig and Schmidt 2004; Tessari et al. 2004). The psychomotor stimulant effects of drugs of abuse are well known to persistently increase after repeated drug administration, a phenomenon known as behavioral sensitization (Stewart and Badiani 1993; Robinson and Berridge 1993; Vanderschuren and Kalivas 2000). Since it is thought that behavioral sensitization is an important driving factor in the development of drug addiction (Robinson and Berridge 1993, 2003; Vanderschuren and Pierce 2010), it is of interest to investigate the involvement of the mGlu5 receptor in psychomotor sensitization. Previous studies have shown that MPEP and MTEP attenuate the expression of morphine-, cocaine-, and nicotine-induced psychomotor sensitization (Tessari et al. 2004; Kotlinska and Bochenski 2007; Kotlinska and Bochenski 2009). However, the role of the mGlu5 receptor in the development of sensitization has remained unexplored. In this regard, it is of interest that mGlu5 receptors have been shown to be involved in the neuroplastic changes underlying learning (Fendt and Schmid 2002; Rodrigues et al. 2002; Gravius et al. 2005; Xu et al. 2009). In view of the mechanistic similarities between drug- and experience-induced behavioral plasticity (Kelley 2004; Hyman et al. 2006), it is possible that mGlu5 receptors are also involved in the development of psychomotor sensitization.

The aim of the present study was to further evaluate the role of the mGlu5 receptor in drug reward and the development of sensitization. To this end, we investigated the effect of the mGlu5 receptor antagonist MTEP and the dopamine receptor antagonist α-flupenthixol on the induction of morphine- and cocaine-induced CPP and psychomotor sensitization. Since the role of dopamine in reward and sensitization is well established, we included the dopamine receptor antagonist in this study for comparison. Mesolimbic dopamine has been widely implicated in the rewarding effects of drugs of abuse (Koob et al. 1998; Wise 2004; Pierce and Kumaresan 2006), but it does not play a critical role in the development of sensitization of the psychomotor stimulant properties of cocaine and morphine (Vanderschuren and Kalivas 2000). Furthermore, it has been shown that mGlu5 receptor stimulation can raise extracellular dopamine in prefrontal cortex and striatum, which can be blocked by, for instance, MPEP or the general mGluR antagonist (+)-MCPG (Bruton et al. 1999; Renoldi et al. 2007). Thus, mGlu5 receptor blockade may reduce the ability of cocaine or morphine to enhance mesolimbic dopamine neurotransmission which may, in turn, attenuate the rewarding effects of these drugs—although cocaine did increase nucleus accumbens dopamine overflow in mGlu5 receptor knockout mice (Chiamulera et al. 2001). We chose to test two types of drug of abuse that differ in their initial actions on the central nervous system. Cocaine inhibits the reuptake of dopamine, serotonin, and noradrenalin into the presynaptic terminal, causing an accumulation of these neurotransmitters in the synaptic cleft and a prolonged receptor stimulation (Heikkila et al. 1975; Ritz et al. 1987), and morphine is an agonist at mu-opioid receptors.

Based on the studies described above, we hypothesized that the mGlu5 receptor is involved in both drug reward and sensitization, while dopamine receptors play a role in reward but not in sensitization. Therefore, we expected that both α-flupenthixol and MTEP would block the development of cocaine- and morphine-induced CPP and that MTEP but not α-flupenthixol would block the development of cocaine- and morphine-induced psychomotor sensitization.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Male Wistar rats (Charles River, Sulzfeld, Germany) weighing 170 ± 15 g upon arrival in the laboratory were used for all experiments. The animals were housed two per cage (Macrolon cages, 40 × 26 × 20 cm) in climate-controlled rooms (temperature, 21 ± 2°C; 60–65% relative humidity) under a 12-h day/night cycle with lights on at 7 am. Regular chow (SDS, England) and water were available ad libitum. The animals were allowed to habituate to the housing conditions for at least 1 week and were handled three times prior to the experiment. Two days before testing, the rats were moved to the experimental room. The experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Utrecht University, the Netherlands, and were conducted in agreement with Dutch laws (Wet op de dierproeven, 1996) and European regulations (Guideline 86/609/EEC).

Place conditioning

Apparatus

The place conditioning apparatus (TSE Systems, Bad Homburg, Germany) consisted of three compartments, and each compartment differed with regard to visual and tactile cues. Two equally sized compartments were used for place conditioning (30 × 25 × 30 cm, l × w × h). The first conditioning compartment had black walls, a fine metal mesh floor, and white light (2 W) in the Plexiglas lid to achieve a comparable light intensity in both conditioning compartments, while the other conditioning compartment had walls with black and white stripes, a wide metal mesh floor, and no light in the Plexiglas lid. Pilot studies performed in our laboratory have shown that the rats had no consistent unconditioned preference for one of the compartments, i.e., there was not one particular compartment that was preferred by the majority of animals during the pretest (see below). The third, middle compartment (10 × 25 × 30 cm) was only used for introducing the animal into the apparatus during the pretest and test sessions. This middle compartment had white walls, a smooth floor, and white light (2 W) in the Plexiglas lid. During the pretest and test sessions, arched gateways gave access to the two adjacent conditioning compartments, which allowed the animals to freely move around the entire apparatus. During conditioning sessions, the rats were placed in one of the two conditioning compartments and access to the other compartments was blocked by inserting dividers without a gateway between the compartments. All compartments were equipped with photo-sensors which detect the location of the animals, and TSE software was used to calculate the total time spent in each compartment.

Procedure

The experiments consisted of three phases: a pretest (session 1), a conditioning period (session 2–9), and a test phase (session 10). The sessions took place once per day and 5 days per week. During the pretest, that took place under drug-free conditions, the rats were free to explore the entire apparatus for 15 min. At the beginning of the pretest the animals were placed in the middle, neutral compartment and we measured the time they spent in each compartment. The rats that spent more than 500 s in one conditioning compartment were excluded from the experiment (in total, 4% of all rats tested). The remaining animals were divided into four groups according to a counterbalanced design (Tzschentke 2007). Thus, on the basis of their pretest scores (i.e., time spent in the two conditioning compartments during the pretest), the rats were assigned to a compartment in which they would receive drug treatment, so that the baseline preference in each test group for the (to be) drug-paired and (to be) saline-paired compartments approximated 50%. Thus, some rats, based on the pretest scores, would be conditioned in their preferred compartment, but others would be conditioned in their non-preferred compartment. This procedure rules out the possibility that preference shifts are the result of decreased avoidance of the non-preferred compartment. During place conditioning, the rats received four drug-paired sessions (session 2, 4, 6, and 8) and four saline-paired sessions (session 3, 5, 7, and 9). The first experiment was performed in order to determine if the doses of α-flupenthixol or MTEP used would induce CPP or conditioned place aversion (CPA) by themselves. Before the start of drug-paired sessions, the rats were injected with one of the following drugs: α-flupenthixol (0 or 0.5 mg/kg, i.p.), 30 min later followed by a saline (1.0 ml/kg, i.p.) injection; MTEP (0 or 10 mg/kg, i.p.), 20 min later followed by a saline injection (1.0 ml/kg, i.p.). Immediately after the saline injection, the animals were placed into the drug-paired compartment for 40 min. Before the start of saline-paired sessions, the rats were injected twice with saline (1.0 ml/kg, i.p.), 20 (in the MTEP experiment) or 30 min (in the α-flupenthixol experiment) apart. The time points of the injections during the saline sessions matched the time point of the injections during the drug-paired sessions. Session 10 consisted of a 15-min test where animals could freely move around the entire apparatus. This test session was carried out under drug-free conditions. Similar as in the pretest-session, the animals were introduced into the apparatus by placing them in the middle, neutral compartment. Next, we measured the time spent in each compartment. In the second set of experiments, we determined the effect of MTEP and α-flupenthixol on cocaine- and morphine-induced place conditioning. Before the start of drug pairing sessions, the rats were injected with one of the following drug combinations: α-flupenthixol (0, 0.125, 0.25, or 0.5 mg/kg, i.p.) 30 min before a cocaine (15 mg/kg, i.p.) or morphine injection (3 mg/kg, s.c.) or MTEP (0, 1, 3, or 10 mg/kg, i.p.) 20 min before a cocaine (15 mg/kg, i.p.) or morphine injection (3 mg/kg, s.c.). Directly after the second injection (i.e., cocaine or morphine), the animals were placed in the drug-paired compartment for 40 min. Vehicle-paired sessions and the test sessions were carried out as described above. The doses of cocaine and morphine were based on pilot studies. Thus, 15 mg/kg cocaine was the lowest dose that induced robust and reproducible CPP, whereas CPP could be induced with morphine at doses of 1 mg/kg and higher.

Psychomotor sensitization

Apparatus

The locomotor activity of rats was measured in open-field test cages (50 × 35 × 40 cm). The horizontal distance traveled was tracked automatically using a video tracking system (Ethovision, Noldus Information Technology BV, Wageningen, Netherlands) which determined the position of the animals five times per second.

Procedure

To determine the effect of MTEP and α-flupenthixol on the induction of cocaine psychomotor sensitization, the rats were pretreated in open-field cages for five consecutive days. During pretreatment sessions, the animals were first allowed to habituate to the open field for 30 min, after which they received an injection of α-flupenthixol (0.5 mg/kg, i.p.), MTEP (1 mg/kg, i.p.), or saline (1 ml/kg, i.p.). At 30 min after the administration of α-flupenthixol or 20 min after the administration of MTEP, the rats were injected with either cocaine (30 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline. The pretreatment dose of cocaine used was based on pilot studies. Thus, we observed robust and reproducible sensitization after repeated treatment with 30 mg/kg (but not 15 mg/kg) cocaine. At 3 weeks after the last pretreatment session, the rats were challenged with cocaine. The challenge session started with a 30-min habituation period. Next, the animals were injected with saline (1 ml/kg, i.p.), and they were injected with cocaine (10 mg/kg, i.p.) 30 min later. The locomotor activity of the animals during all sessions was monitored from the time of introduction to the open field until 60 min after the cocaine injection. To determine the effect of MTEP and α-flupenthixol on the induction of morphine psychomotor sensitization, the animals were pretreated for ten sessions (five sessions a week). During pretreatment sessions, the animals were allowed to habituate to the open field for 30 min, after which they were injected with α-flupenthixol (0.5 mg/kg, i.p.), MTEP (1.0 mg/kg, i.p.), or saline (1.0 ml/kg, i.p.). At 30 min after the first injection, the rats were injected with either morphine (3.0 mg/kg, s.c.) or saline (1.0 ml/kg, s.c.). The pretreatment dose of morphine used was based on pilot studies. Thus, we observed robust and reproducible sensitization after repeated treatment doses of 1 mg/kg morphine and higher. At 3 weeks after the last pretreatment session, the animals were challenged with morphine (1.0 mg/kg, s.c.). The procedure of the challenge session was similar to the cocaine challenge session described above. During all sessions, locomotor activity was monitored from the time of introduction to the open field until 90 min after the last injection.

Statistics

Place conditioning data are expressed as mean time spent in drug- or vehicle-paired compartments ± S.E.M. (in seconds). Outliers, identified using Dixon outlier test, were excluded from the analyses (1.6% of all animals). To determine the occurrence of CPP, we analyzed each group using Student’s t-test for paired samples, comparing the time spent in the drug-paired with the time spent in the saline-paired compartment. For the psychomotor sensitization experiments, horizontal activity is expressed as mean ± S.E.M. distance traveled (in centimeters). The locomotor responses during the pretreatment sessions are presented as mean ± S.E.M. distance traveled during 60 min after cocaine or saline injection or as the mean ± S.E.M. distance traveled during 90 min after morphine or saline injection. Data were analyzed using a three-way repeated-measures ANOVA with sessions as within-subjects factor and the receptor antagonists (MTEP or α-flupenthixol) and the drug used to induce psychomotor sensitization (cocaine or morphine) as two between-subjects factors. During the challenge sessions, the distance traveled was analyzed in 10-min blocks. Data were analyzed using a three-way repeated-measures ANOVA with time blocks as within-subjects factor and receptor antagonists (MTEP or α-flupenthixol) and the drug used to induce psychomotor sensitization (cocaine or morphine) as two between-subjects factors. Post-hoc comparisons were made where appropriate using Student–Newman–Keuls tests. Behavioral data were analyzed using SPSS 15.0. The criterion for statistically significant differences was set at p < 0.05

Drugs

MTEP (3-[(2-methyl-1,3-thiazol-4-yl) ethynyl] pyridine) was a generous gift from Dr. Will Spooren (F. Hoffman-la Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland). The MTEP doses used were based on literature (Anderson et al. 2002; Cosford et al. 2003) and pilot studies. MTEP, cocaine–HCl (Bufa BV, Uitgeest, The Netherlands), morphine–HCl (OPG Regilabs bv, Utrecht, The Netherlands), and cis-(Z)-α-flupenthixol dihydrochloride (Sigma, Zwijndrecht, The Netherlands) were dissolved in sterile physiological saline (0.9% NaCl).

Results

Place conditioning effect of MTEP and α-flupenthixol

Figure 1 shows that MTEP and α-flupenthixol, at the highest doses used in this study, did not induce CPP or CPA compared with saline. Moreover, the animals repeatedly treated with saline in both compartments of the place conditioning apparatus did not develop a preference for one compartment or the other, demonstrating that repeated exposure to the apparatus did not induce a preference for one particular set of environmental cues [MTEP: t(sal)7 = −1.351 NS, t(MTEP)7 = 0.642 NS; α-flupenthixol t(sal)7 = −0.742 NS, t(α-flupenthixol)7 = −0.258 NS].

The effect of MTEP- and α-flupenthixol on place conditioning. a Rats were conditioned with saline in both compartments (n = 8) or with 10 mg/kg MTEP, i.p., in one compartment and saline in the other (n = 8). b Rats were conditioned with saline in both compartments (n = 8) or with 0.5 mg/kg α-flupenthixol, i.p., in one compartment and saline in the other (n = 8). Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. time spent in drug-paired and saline compartment on test day

Effect of MTEP and α-flupenthixol on cocaine-induced place conditioning

In animals pretreated with saline, cocaine induced significant preference for the drug-paired compartment in both experiments. The acquisition of cocaine-induced CPP was not affected by MTEP. In this experiment, one rat from the saline, one rat from the 3 mg/kg, and one rat from the 10 mg/kg group were excluded from analysis as outliers. Figure 2a shows that cocaine-induced CPP was present in all groups independent of MTEP treatment [sal: t 6 = 5.413 p < 0.01; 1 mg/kg MTEP: t 7 = 4.066 p < 0.01; 3 mg/kg MTEP: t 6 = 7.554 p < 0.001; 10 mg/kg MTEP: t 6 = 5.455 p < 0.01]. On the other hand, α-flupenthixol attenuated the acquisition of cocaine-induced CPP. In this experiment, one animal from the 0.125 mg/kg α-flupenthixol group was excluded as an outlier. Figure 2b shows that cocaine no longer induced CPP when 0.25 and 0.5 mg/kg α-flupenthixol was co-administered during conditioning [sal: t 15 = 3.134 P < 0.01; 0.125 mg/kg flupenthixol: t 13 = 4.569 p < 0.001; 0.25 mg/kg flupenthixol: t 14 = 0.546 NS; 0.5 mg/kg flupenthixol: t 14 = 1.590 NS].

The effect of MTEP and α-flupenthixol on the development of cocaine-induced CPP. a Rats were conditioned with cocaine (15 mg/kg, i.p.) together with saline (0; n = 7), 1 (n = 8), 3 (n = 7), or 10 (n = 7) mg/kg, i.p., MTEP. b Rats were conditioned with cocaine (15 mg/kg, i.p.) together with saline (0; n = 16), 0.125 (n = 14), 0.25 (n = 15), or 0.5 (n = 15) mg/kg, i.p., α-flupenthixol. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. time spent in drug- and saline-paired compartment on test day. *p < 0.05 for difference in time spent in drug- and saline-paired compartment (Student’s t-test)

Effect of MTEP and α-flupenthixol on morphine-induced place conditioning

In animals pretreated with saline, morphine induced a significant preference for the drug-paired compartment in both experiments. The acquisition of morphine-induced place preference was suppressed by MTEP. Figure 3a shows that, when 1 and 3 mg/kg MTEP was co-administered with morphine during conditioning, no morphine-induced CPP developed [sal: t 14 = 4.240 p < 0.05; 1 mg/kg MTEP: t 13 = 1.346 NS; 3 mg/kg MTEP: t 14 = 0.382 NS]. However, 10 mg/kg MTEP did not attenuate place preference [t 14 = 2.381 p < 0.05]. α-Flupenthixol attenuated the acquisition of morphine-induced CPP. Figure 3b shows that the highest dose of α-flupenthixol significantly reduced morphine-induced CPP [sal: t 15 = 2.669 P < 0.05; 0.125 mg/kg flupenthixol: t 15 = 6.104 P < 0.001; 0.25 mg/kg flupenthixol: t 14 = 4.890 P < 0.001; 0.5 mg/kg flupenthixol: t 15 = 1.677 NS].

The effect of MTEP and α-flupenthixol on the development of morphine-induced CPP. a Rats were conditioned with morphine (3 mg/kg, s.c.) together with saline (0; n = 15), or 1 (n = 14), 3 (n = 15), or 10 (n = 15) mg/kg, i.p. MTEP. b Rats were conditioned with morphine (3 mg/kg, s.c.) together with saline (0; n = 16), or 0.125 (n = 16), 0.25 (n = 15), or 0.5 (n = 16) mg/kg, i.p., α-flupenthixol. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. time spent in drug- and saline-paired compartment on test day. *p < 0.05 for difference in time spent in drug-paired and saline-paired compartment (Student’s t-test)

The effects of MTEP and α-flupenthixol on psychomotor activity during cocaine and morphine pretreatment

Figure 4 shows the psychomotor effects of cocaine, MTEP, and α-flupenthixol during the first and last (i.e., fifth) day of pretreatment. Figure 4a shows that cocaine treatment enhanced psychomotor activity during the pretreatment sessions [F(cocaine)1,28 = 28.504 p < 0.001], but no sensitization to cocaine was observed during pretreatment [F(session × coc)1, 28 = 0.784 NS]. MTEP did not alter the cocaine-induced psychomotor response [F(MTEP × cocaine)1,28 = 2.190 NS; F (session × MTEP × coc)1,28 = 0.041 NS], neither did MTEP influence the psychomotor activity by itself [F(MTEP)1,28 = 1.486 NS; F(session × MTEP)1,28 = 0.240 NS]. Figure 4b shows that cocaine treatment increased psychomotor activity during pretreatment sessions [F(cocaine)1,32 = 36.827 p < 0.001], that this effect of cocaine did not sensitize [F(session × cocaine)1,32 = 0.008 NS], and that α-flupenthixol did not affect the cocaine-induced psychomotor activity during the pretreatment sessions [F(α-flupenthixol × cocaine)1,32 = 2.841 NS; F(session × α-flupenthixol × cocaine)1,32 = 2.841 NS]. In addition, α-flupenthixol itself did not influence psychomotor activity [F(α-flupenthixol)1,32 = 4.052 NS; F(session × α-flupenthixol)1,32 = 0.008 NS].

The effects of MTEP and α-flupenthixol on the locomotor response to cocaine during pretreatment. a Locomotor responses to cocaine (coc; 30 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline (sal) in rats treated 20 min before with MTEP (1.0 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline (sal) (n = 8 per group). b Locomotor responses to cocaine (coc; 30 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline (sal) in rats treated 30 min before with α-flupenthixol (flu; 0.5 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline (sal) (n = 9 per group). Locomotor responses were measured on days 1 and 5 of pretreatment. Data are presented as total distance traveled (cm) in 1 h after cocaine or saline, expressed in mean ± S.E.M.

Figure 5 shows the psychomotor effects of morphine, MTEP, and flupenthixol during the first and last (i.e., tenth) day of pretreatment. Figure 5a shows that MTEP did not affect morphine-induced psychomotor activity during pretreatment. Sensitization to morphine was observed during pretreatment since the morphine-induced psychomotor activity increased over sessions [F(morphine)1,19 = 10.296 p < 0.01; F(session × morphine)1,19 = 16.716 p = 0.001]. MTEP did not alter the morphine-induced psychomotor activity during these sessions [F(MTEP × morphine)1,19 = 1.965 NS; F(session × MTEP × morphine)1,19 = 0.503 NS] and MTEP did not affect the activity by itself [F(MTEP)1,19 = 0.274 NS; F(session × MTEP)1,19 = 1.965 NS]. Figure 5b shows that α-flupenthixol did not affect the morphine-induced psychomotor activity during the pretreatment sessions. During these sessions, morphine did not induce an increase in psychomotor activity [F(morphine)1,17 = 2.561 NS; F(session × morphine)1,17 = 3.349 NS]. The absence of morphine sensitization during pretreatment was caused by one control rat showing a highly increased activity only during the tenth pretreatment session. Treatment with α-flupenthixol did not affect the morphine-induced psychomotor activity [F(α-flupenthixol × morphine)1,17 =0.007 NS; F(session × α-flupenthixol × morphine)1,17 = 0.004 NS] and did not affect activity by itself [F(α-flupenthixol)1,17 = 1.709 NS; F(session × α-flupenthixol)1,17 = 0.519 NS].

The effects of MTEP and α-flupenthixol on the locomotor response to morphine during pretreatment. a Locomotor responses to morphine (morp; 3.0 mg/kg , s.c.) or saline (sal) in rats treated 30 min before with MTEP (1.0 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline (sal) (n = 8 per group). b Locomotor responses to morphine (morp; 3.0 mg/kg, s.c.) or saline (sal) in rats treated 30 min before with α-flupenthixol (flu; 0.5 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline (sal) (n = 9 per group). Locomotor responses were measured on days 1 and 10 of pretreatment. Data are presented as total distance traveled (cm) in 1 h after morphine or saline, expressed in mean ± S.E.M.

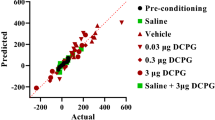

The effect of MTEP and α-flupenthixol on cocaine- and morphine-induced psychomotor sensitization

Figure 6a shows that, during the habituation phase of the challenge session, there was an effect of cocaine pretreatment [F(cocaine)1,28 = 4.714 p = 0.039], but no effect of MTEP pretreatment[F(MTEP)1,28 = 1.378 NS; F(MTEP × cocaine)1,28 = 2.234 NS]. After the saline injection, there was no effect of cocaine or MTEP pretreatment [F(cocaine)1,28 = 0.000 NS; F(MTEP)1,28 = 0.070 NS], but there was an interaction between cocaine and MTEP [F(MTEP × cocaine)1,28 = 4.646 p < 0.05]. Cocaine pretreatment resulted in a sensitized psychomotor response to a low dose of cocaine [F(cocaine)1,28 = 9.282 p < 0.01; F(time blocks × cocaine)1,28 = 16.158 p < 0.001], and co-administration of MTEP during pretreatment suppressed this sensitized cocaine-induced psychomotor response [F(MTEP)1,28 = 8.506 p < 0.01; F(time blocks × MTEP)1,28 = 1.781 p < 0.01; F(MTEP × cocaine)1,28 = 8.651 p < 0.01; F(time blocks × MTEP × cocaine)1,28 = 7.249 p < 0.01].

a Locomotor responses to cocaine (10 mg/kg, i.p.), in animals pretreated for 5 days with: saline plus saline (sal-sal; n = 8), saline plus 30 mg/kg cocaine, i.p. (sal-coc; n = 8), 1.0 mg/kg MTEP, i.p., plus saline (mtep-sal; n = 8) or 1.0 mg/kg MTEP, i.p., plus 30 mg/kg cocaine, i.p. (mtep-coc; n = 8) 3 weeks post-treatment. b Locomotor responses to cocaine (10 mg/kg, i.p.) in animals pretreated for 5 days with: saline plus saline (sal-sal; n = 9), saline plus 30 mg/kg cocaine, i.p. (sal-coc; n = 9), 0.5 mg/kg α-flupenthixol, i.p., plus saline (flu-sal; n = 9), or 0.5 mg/kg α-flupenthixol, i.p., plus 30 mg/kg cocaine, i.p. (flu-coc; n = 9), 3 weeks post-treatment. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. distance traveled (in cm) per 10 min during habituation to the test cages (10–30 min), after a saline injection (40–60 min), and after the cocaine challenge (10 mg/kg, i.p., 70–120 min)

Figure 6b shows that cocaine-induced psychomotor sensitization was not altered by α-flupenthixol pretreatment. Neither cocaine nor α-flupenthixol pretreatment affected the locomotor responses during the habituation phase and after the saline challenge [habituation: F(cocaine)1,32 = 0.184 NS; saline: F(cocaine)1,32 = 0.049 NS; habituation: F(α-flupenthixol)1,32 = 0.443 NS; saline: F(flupenthixol)1,32 = 0.054 NS; habituation: F(α-flupenthixol × cocaine)1,32 = 1.925 NS; saline: F(α-flupenthixol × cocaine)1,32 = 1.273 NS]. After the challenge with cocaine, the animals pretreated with cocaine showed an increased locomotor response [F(cocaine)1,32 = 8.863 p < 0.01; F(time blocks × cocaine)1,32 = 11.550 p < 0.001]. α-Flupenthixol pretreatment did not influence this sensitized response [F(α-flupenthixol)1,32 = 0.266 NS; F(time blocks × α-flupenthixol)1,32 = 0.669 NS; F(α-flupenthixol × cocaine)1,32 = 1.195 NS; F(time blocks × α-flupenthixol × cocaine)1,32 = 0.921 NS].

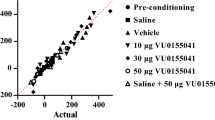

Figure 7a shows that morphine-induced locomotor sensitization during the challenge session was not altered by MTEP pretreatment. During the habituation phases and the 30 min after the saline injections, neither morphine nor MTEP pretreatment affected the locomotor responses [habituation: F(morphine)1,19 = 1.155 NS; F(MTEP)1,19 = 0.330 NS; F(MTEP × morphine)1,19 = 0.161 NS; saline: F(morphine)1,19 = 2.747 NS; F(MTEP)1,19 = 0.057 NS; F(MTEP × morphine)1,19 = 0.803 NS]. After the challenge with morphine, a sensitized locomotor response was observed in morphine-pretreated animals [F(morphine)1,19 = 16.373 p = 0.001; F(time blocks × morphine)1,19 = 2.591 NS]. MTEP pretreatment did not alter morphine sensitization [F(MTEP)1,19 = 0.845 NS; F(time blocks × MTEP)1,19 = 0.408 NS; F(morphine × MTEP)1,19 = 0.633 NS; F(session × MTEP × morphine)1,19 = 0.669 NS].

a Locomotor responses to morphine (1.0 mg/kg, s.c.) in animals pretreated for 5 days with: saline plus saline (sal-sal; n = 6), saline plus 3.0 mg/kg morphine, s.c., (sal-morp; n = 5), 1.0 mg/kg MTEP, i.p., plus saline (mtep-sal; n = 6) or 1.0 mg/kg MTEP, i.p., plus 3.0 mg/kg morphine, s.c. (mtep-morp; n = 6), 3 weeks post-treatment. b Locomotor responses to morphine (1.0 mg/kg, s.c.) in animals pretreated for 5 days with: saline plus saline (sal-sal; n = 5), saline plus 3.0 mg/kg morphine, s.c. (sal-morp; n = 5), 0.5 mg/kg α-flupenthixol, i.p., plus saline (flu-sal; n = 5) or 0.5 mg/kg α-flupenthixol, i.p., plus 3.0 mg/kg morphine, s.c. (flu-morp; n = 6), 3 weeks post-treatment. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. distance traveled (in cm) per 10 min during habituation to the test cages (10–30 min), after a saline injection (40–60 min), and after the morphine challenge (1.0 mg/kg, s.c., 70–150 min)

Figure 7b shows that morphine-induced locomotor sensitization during the challenge session was not altered by α-flupenthixol pretreatment. Neither morphine nor α-flupenthixol pretreatment influenced the locomotor responses of the animals during the habituation phase and after the saline injection of the challenge session [habituation: F(morphine)1,17 = 0.013 NS; F(α-flupenthixol)1,17 = 3.189 NS; F(α-flupenthixol × morphine)1,17 = 0.278 NS; saline: F(morphine)1,17 = 0.302 NS; F(α-flupenthixol)1,17 = 0.845 NS; F(α-flupenthixol × morphine)1,17 = 1.085 NS]. The morphine challenge induced an increased locomotor response in animals that were pretreated with morphine [F(morphine)1,17 = 22.686 p < 0.001; F(time blocks × morphine) 1,17 = 2.775 p < 0.05], but α-flupenthixol had no influence on this response [F(α-flupenthixol)1,17 = 2.257 NS; F(time blocks × α-flupenthixol)1,17 = 0.460 NS; F(morphine × α-flupenthixol)1,17 = 1.110 NS; F(session × α-flupenthixol × morphine)1,17 = 0.372 NS].

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the role of mGlu5 and dopamine receptors in the rewarding and sensitizing properties of cocaine and morphine. To that aim, we administered the mGlu5 receptor antagonist MTEP and the dopamine receptor antagonist α-flupenthixol during the development of cocaine and morphine CPP and psychomotor sensitization. In agreement with our hypotheses, co-administration of α-flupenthixol during place conditioning with morphine and cocaine attenuated CPP, but α-flupenthixol did not affect the development of cocaine- and morphine-induced psychomotor sensitization.

However, the results with MTEP only partially confirmed our hypotheses. Co-administration of MTEP during place conditioning with morphine attenuated morphine-induced CPP, whereas MTEP treatment during cocaine conditioning did not affect the development of cocaine-induced CPP. MTEP blocked the development of psychomotor sensitization to cocaine, but not morphine.

Place conditioning

MTEP attenuated morphine-induced CPP when 1 or 3 mg/kg, but not when 10 mg/kg was co-administered during conditioning. This suggests that mGlu5 receptors play a role in mediating morphine reward. These results are in agreement with other studies in which MPEP attenuated the development of morphine-induced CPP (Popik and Wrobel 2002; Aoki et al. 2004; Herzig and Schmidt 2004). However, other studies have shown that MPEP had no effect on morphine CPP (McGeehan and Olive 2003) and actually potentiated heroin-induced CPP (van der Kam et al. 2009a). Because MTEP and MPEP can cause deficits in spatial learning (Naie and Manahan-Vaughan 2004; Gravius et al. 2008; Bikbaev et al. 2008), it is possible that MTEP impaired learning, i.e., the establishment of an association between the environmental cues in the morphine-paired compartment and the rewarding properties of the drug (see also Fendt and Schmid 2002; Rodrigues et al. 2002; Gravius et al. 2005; Xu et al. 2009), without effectively influencing the rewarding effects of morphine. However, MTEP did not suppress cocaine-induced CPP, which suggests that learning of an environment–reward association was intact in MTEP-treated animals. It is therefore unlikely that the effect of MTEP on morphine CPP is the result of impairment in learning. We do not have a straightforward explanation for the finding that 10 mg/kg MTEP did not influence morphine CPP. It might be that an off-target effect of MTEP is responsible for this lack of effect. In vitro essays have shown that high concentrations of MTEP inhibit monoamine oxidase A and NR1a/2B-containing NMDA receptors, but it is unlikely that the dose of 10 mg/kg, i.p., MTEP resulted in brain concentrations high enough to elicit these effects (Cosford et al. 2003; Nagel et al. 2007). Alternatively, the repeated injection of 10 mg/kg MTEP may have evoked tolerance to the effects of the drug. Indeed, the repeated administration of MTEP can lead to tolerance into its analgesic and anxiolytic effects (Busse et al. 2004; Sevostianova and Danysz 2006).

In the present study, MTEP did not affect cocaine-induced CPP. This suggests that stimulation of mGlu5 receptors is not critical for cocaine reward. This finding stands in contrast to studies showing that MPEP blocks the development of cocaine CPP (Herzig and Schmidt 2004; McGeehan and Olive 2003). Interestingly, recent studies have shown that MPEP potentiates the development of CPP induced by subeffective doses of cocaine, nicotine, ketamine, and heroin (van der Kam et al. 2009a; Rutten et al. 2010). Since effective doses of cocaine and morphine were used in the present study, a potentiation of the development of CPP by MTEP was not likely to be detected. However, the MPEP that was used in these previous studies is a less selective mGlu5 receptor antagonist than MTEP, since it can also bind to NMDA receptors (O'Leary et al. 2000; Cosford et al. 2003). It is well known that NMDA receptor antagonists block the development of cocaine and morphine CPP (Cervo and Samanin 1995; Maldonado et al. 2007; Tzschentke and Schmidt 1995; Tzschentke and Schmidt 1997) but can also potentiate the reinforcing effects of drugs and have reinforcing effects themselves (Vanderschuren et al. 1998). It is therefore possible that the earlier observed effects with MPEP on the development of CPP were the result of NMDA receptor blockade. Future studies must reveal whether MTEP can augment the development of CPP induced by subeffective doses of drugs.

The results of the present study are consistent with the well-established role of dopamine receptor stimulation in the rewarding properties of cocaine and morphine (Koob et al. 1998; van Ree et al. 1999; Wise 2004; Pierce and Kumaresan 2006; but see Spyraki et al. 1982; Mackey and van der Kooy 1985). We used the non-selective dopamine receptor antagonist α-flupenthixol that targets both dopamine D1 and D2 receptors. The dopamine D1 receptor has widely been implicated in drug reward. Multiple studies have shown that the D1 receptor antagonist SCH23390 blocks the development of both cocaine- and morphine-induced CPP (cocaine: Cervo and Samanin 1995; Shippenberg and Heidbreder 1995; Baker et al. 1998; Nazarian et al. 2004; morphine: Leone and Di Chiara 1987; Shippenberg and Herz 1988; Acquas et al. 1989; Acquas and Di Chiara 1994; Manzanedo et al. 2001). In contrast to dopamine D1 receptors, dopamine D2 receptors do not seem to be critical for the development of cocaine-induced CPP (Cervo and Samanin 1995; Shippenberg and Heidbreder 1995; Nazarian et al. 2004). With regard to morphine-induced CPP, there have been reports that dopamine D2 receptor antagonists block the development of morphine-induced CPP (Leone and Di Chiara 1987; Manzanedo et al. 2001), while others have reported no effect (Shippenberg and Herz 1988).

In the Introduction we mentioned that mGlu5 receptors may be involved in drug reward via downstream modulation of mesolimbic dopamine activity. However, our results, showing partially divergent effects of MTEP and α-flupenthixol on drug-induced CPP, do not support this possibility. Thus, whereas α-flupenthixol blocked the development of both cocaine- and morphine–induced CPP, MTEP attenuated only the development of morphine-induced CPP. The rewarding properties of cocaine depend more strongly on dopaminergic neurotransmission than morphine reward (van Ree et al. 1999; Pierce and Kumaresan 2006). Therefore, the finding that MTEP only attenuated the process least dependent on dopaminergic neurotransmission indicates that MTEP influences drug reward through mechanisms that are relatively dopamine–independent. The exact mechanism of action of MTEP on morphine-induced CPP remains to be elucidated. Interestingly, stimulation of nucleus accumbens mGlu5 receptors has been shown to enhance endocannabinoid activity (Robbe et al. 2002), and unlike cocaine reward the rewarding properties of opiates strongly depend on endocannabinoid signaling (e.g., Cossu et al. 2001; De Vries et al. 2003; for reviews see Maldonado et al. 2006; Solinas et al. 2008). One intriguing possibility is therefore that blockade of nucleus accumbens mGlu5 receptors reduces opioid-induced endocannabinoid activity, which diminishes the rewarding properties of morphine. Indeed, enhanced nucleus accumbens endocannabinoid activity plays a prominent role in heroin but not cocaine self-administration, independent of nucleus accumbens dopamine activity (Caille and Parsons 2003, 2006; Caille et al. 2007).

It can be excluded that MTEP or α-flupenthixol affected place conditioning because of any aversive or rewarding properties of the antagonists themselves. When MTEP or α-flupenthixol was administered during place conditioning in the absence of cocaine or morphine, neither substance induced a preference or aversion for the antagonist-paired compartment.

Taken together, the present study suggests that dopamine receptors are critically involved in cocaine and morphine reward and that mGlu5 receptors play an important role in morphine but not cocaine reward.

Psychomotor sensitization

In the present study, α-flupenthixol was unable to alter the development of cocaine- and morphine-induced locomotor sensitization. This supports the notion that dopaminergic neurotransmission is not critical for the induction of cocaine and morphine sensitization (Vanderschuren and Kalivas 2000). Similar findings have been reported with both D1 and D2 receptor antagonists, i.e., SCH 23390, sulpride, eticlopride, and YM-09151-2 (cocaine: Mattingly et al. 1994; Kuribara 1995; White et al. 1998; morphine: Vezina and Stewart 1989; Jeziorski and White 1995). It is unlikely that the dose of 0.5 mg/kg α-flupenthixol was too low to affect the development of psychomotor sensitization. Even though α-flupenthixol did not alter locomotor activity during pretreatment sessions, this dose of α-flupenthixol was sufficient to block the rewarding effects of cocaine in the place conditioning experiment. Furthermore, it has been repeatedly shown that doses of dopaminergic drugs that do reduce the psychomotor stimulant effects of cocaine and morphine do not block the development of sensitization (Vezina and Stewart 1989; Mattingly et al. 1994; Jeziorski and White 1995; Kuribara 1995; White et al. 1998).

MTEP blocked the development of cocaine-induced psychomotor sensitization without affecting the acute psychomotor responses to cocaine. Consistent with the latter observation, Herzig and Schmidt (2004) have shown that MPEP does not affect cocaine- and morphine-induced psychomotor activity. However, they did not challenge their animals with cocaine or morphine in the absence of MPEP after a period of abstinence, which left the question on whether mGlu5 receptors are involved in the development of locomotor sensitization open. Previously, Ghasemzadeh et al. (1999, 2009) have shown an increase in mGlu5 receptor mRNA level in the nucleus accumbens shell and dorsolateral striatum and an augmented mGlu5 receptor protein level in the synaptosomal membrane of the nucleus accumbens shell and core in cocaine-sensitized animals. This suggests a link between the development of cocaine sensitization and mGlu5 receptors, but ours is the first pharmacological intervention study that demonstrates a critical role for mGlu5 receptors in the development of cocaine-induced psychomotor sensitization. In contrast, even though repeated morphine treatment has been shown to result in an increase in mGlu5 protein level in the nucleus accumbens (Aoki et al. 2004), MTEP did not attenuate morphine psychomotor sensitization.

The explanation for why mGlu5 receptors are involved in the development of psychomotor sensitization to cocaine but not to morphine might lie in the differential interactions of these drugs with glutamatergic neurotransmission. For instance, cocaine increases extracellular glutamate levels in various brain regions of drug-naïve animals (Smith et al. 1995; Reid et al. 1997; McKee and Meshul 2005) and repeated cocaine administration results in the sensitization of cocaine-induced extracellular glutamate levels in the nucleus accumbens and ventral tegmental area (Pierce et al. 1996; Reid and Berger 1996; Kalivas and Duffy 1998; Bell et al. 2000). In contrast, morphine administration initially results in decreases in extracellular glutamate levels in various brain regions, including the nucleus accumbens and dorsal striatum (Sepulveda et al. 1998; Desole et al. 1996; Enrico et al. 1998). With repeated treatment, tolerance develops to this effect of morphine on extracellular glutamate levels (Sepulveda et al. 1998; Desole et al. 1996). Together, brain glutamate release responds more strongly to cocaine than to morphine, which makes it more likely that mGlu5 receptors become activated by repeated cocaine administration than by morphine. In this regard, the dissociable role of mGlu5 receptors in the development of cocaine and morphine psychomotor sensitization is reminiscent of the role of NMDA receptors in these processes. It is well established that NMDA receptors are involved in the development of cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization (Scheggi et al. 2002; Vanderschuren and Kalivas 2000; Wolf and Jeziorski 1993), but the evidence that NMDA receptors are important for the development of morphine sensitization is inconsistent (Jeziorski et al. 1994; Tzschentke and Schmidt 1996; Vanderschuren et al. 1997; Ranaldi et al. 2000; Scheggi et al. 2002). Alternatively, since morphine pretreatment lasted for 10 days, compared to 5 days of cocaine pretreatment, the possibility that tolerance to the effect of MTEP developed over repeated dosing cannot be excluded. Thus, it might be that tolerance to the effect of MTEP, although this has thus far only been demonstrated for doses of 3 mg/kg and higher (Busse et al. 2004; Sevostianova and Danysz 2006), explains the lack of effect of MTEP on the development of morphine sensitization.

Conclusions

The present study shows that the role of mGlu5 receptors in reward and sensitization is distinct for morphine and cocaine. Although mGlu5 receptor antagonists have been proposed to hold promise for the treatment of drug addiction, recent studies have shown that the role of the mGlu5 receptor in addictive behavior is not as straightforward as initially assumed (van der Kam et al. 2009a; 2009b; Hao et al. 2010; Rutten et al. 2010). Therefore, caution should be taken not to overgeneralize the anti-addictive properties of mGlu5 receptor ligands.

References

Acquas E, Carboni E, Leone P, Di Chiara G (1989) SCH 23390 blocks drug-conditioned place-preference and place-aversion: anhedonia (lack of reward) or apathy (lack of motivation) after dopamine-receptor blockade? Psychopharmacology 99:151–155

Acquas E, Di Chiara G (1994) D1 receptor blockade stereospecifically impairs the acquisition of drug-conditioned place preference and place aversion. Behav Pharmacol 5:555–569

Anderson JJ, Rao SP, Rowe B, Giracello DR, Holtz G, Chapman DF, Tehrani L, Bradbury MJ, Cosford ND, Varney MA (2002) [3H]Methoxymethyl-3-[(2-methyl-1, 3-thiazol-4-yl)ethynyl]pyridine binding to metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 in rodent brain: in vitro and in vivo characterization. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 303:1044–1051

Aoki T, Narita M, Shibasaki M, Suzuki T (2004) Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 localized in the limbic forebrain is critical for the development of morphine-induced rewarding effect in mice. Eur J Neurosci 20:1633–1638

Baker DA, Fuchs RA, Specio SE, Khroyan TV, Neisewander JL (1998) Effects of intraaccumbens administration of SCH-23390 on cocaine-induced locomotion and conditioned place preference. Synapse 30:181–193

Bell K, Duffy P, Kalivas PW (2000) Context-specific enhancement of glutamate transmission by cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology 23:335–344

Besheer J, Faccidomo S, Grondin JJ, Hodge CW (2008) Regulation of motivation to self-administer ethanol by mGluR5 in alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 32:209–221

Bikbaev A, Neyman S, Ngomba RT, Conn J, Nicoletti F, Manahan-Vaughan D (2008) MGluR5 mediates the interaction between late-LTP, network activity, and learning. PLoS ONE 3:e2155

Bisaga A, Popik P, Bespalov AY, Danysz W (2000) Therapeutic potential of NMDA receptor antagonists in the treatment of alcohol and substance use disorders. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 9:2233–2248

Bruton RK, Ge J, Barnes NM (1999) Group I mGlu receptor modulation of dopamine release in the rat striatum in vivo. Eur J Pharmacol 369:175–181

Busse CS, Brodkin J, Tattersall D, Anderson JJ, Warren N, Tehrani L, Bristow LJ, Varney MA, Cosford ND (2004) The behavioral profile of the potent and selective mGlu5 receptor antagonist 3-[(2-methyl-1,3-thiazol-4-yl)ethynyl]pyridine (MTEP) in rodent models of anxiety. Neuropsychopharmacology 29:1971–1979

Caille S, Alvarez-Jaimes L, Polis I, Stouffer DG, Parsons LH (2007) Specific alterations of extracellular endocannabinoid levels in the nucleus accumbens by ethanol, heroin, and cocaine self-administration. J Neurosci 27:3695–3702

Caille S, Parsons LH (2003) SR141716A reduces the reinforcing properties of heroin but not heroin-induced increases in nucleus accumbens dopamine in rats. Eur J Neurosci 18:3145–3149

Caille S, Parsons LH (2006) Cannabinoid modulation of opiate reinforcement through the ventral striatopallidal pathway. Neuropsychopharmacology 31:804–813

Cervo L, Samanin R (1995) Effects of dopaminergic and glutamatergic receptor antagonists on the acquisition and expression of cocaine conditioning place preference. Brain Res 673:242–250

Chiamulera C, Epping-Jordan MP, Zocchi A, Marcon C, Cottiny C, Tacconi S, Corsi M, Orzi F, Conquet F (2001) Reinforcing and locomotor stimulant effects of cocaine are absent in mGluR5 null mutant mice. Nat Neurosci 4:873–874

Cosford ND, Tehrani L, Roppe J, Schweiger E, Smith ND, Anderson J, Bristow L, Brodkin J, Jiang X, McDonald I et al (2003) 3-[(2-Methyl-1, 3-thiazol-4-yl)ethynyl]-pyridine: a potent and highly selective metabotropic glutamate subtype 5 receptor antagonist with anxiolytic activity. J Med Chem 46:204–206

Cossu G, Ledent C, Fattore L, Imperato A, Bohme GA, Parmentier M, Fratta W (2001) Cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mice fail to self-administer morphine but not other drugs of abuse. Behav Brain Res 118:61–65

De Vries TJ, Homberg JR, Binnekade R, Raaso H, Schoffelmeer ANM (2003) Cannabinoid modulation of the reinforcing and motivational properties of heroin and heroin-associated cues in rats. Psychopharmacology 168:164–169

Desole MS, Esposito G, Fresu L, Migheli R, Enrico P, Mura MA, De Natale G, Miele E, Miele M (1996) Effects of morphine treatment and withdrawal on striatal and limbic monoaminergic activity and ascorbic acid oxidation in the rat. Brain Res 723:154–161

Enrico P, Mura MA, Esposito G, Serra P, Migheli R, De Natale G, Desole MS, Miele M, Miele E (1998) Effect of naloxone on morphine-induced changes in striatal dopamine metabolism and glutamate, ascorbic acid and uric acid release in freely moving rats. Brain Res 797:94–102

Fendt M, Schmid S (2002) Metabotropic glutamate receptors are involved in amygdaloid plasticity. Eur J Neurosci 15:1535–1541

Gass JT, Olive MF (2008) Glutamatergic substrates of drug addiction and alcoholism. Biochem Pharmacol 75:218–265

Gass JT, Osborne MP, Watson NL, Brown JL, Olive MF (2009) mGluR5 antagonism attenuates methamphetamine reinforcement and prevents reinstatement of methamphetamine-seeking behavior in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 34:820–833

Ghasemzadeh MB, Mueller C, Vasudevan P (2009) Behavioral sensitization to cocaine is associated with increased glutamate receptor trafficking to the postsynaptic density after extended withdrawal period. Neuroscience 159:414–426

Ghasemzadeh MB, Nelson LC, Lu XY, Kalivas PW (1999) Neuroadaptations in ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptor mRNA produced by cocaine treatment. J Neurochem 72:157–165

Gravius A, Dekundy A, Nagel J, More L, Pietraszek M, Danysz W (2008) Investigation on tolerance development to subchronic blockade of mGluR5 in models of learning, anxiety, and levodopa-induced dyskinesia in rats. J Neural Transm 115:1609–1619

Gravius A, Pietraszek M, Schafer D, Schmidt WJ, Danysz W (2005) Effects of mGlu1 and mGlu5 receptor antagonists on negatively reinforced learning. Behav Pharmacol 16(2):113–121

Hao Y, Martin-Fardon R, Weiss F (2010) Behavioral and functional evidence of metabotropic glutamate receptor 2/3 and metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 dysregulation in cocaine-escalated rats: factor in the transition to dependence. Biol Psychiatry 68:240–248

Heidbreder CA, Hagan JJ (2005) Novel pharmacotherapeutic approaches for the treatment of drug addiction and craving. Curr Opin Pharmacol 5:107–118

Heikkila RE, Orlansky H, Mytilineou C, Cohen G (1975) Amphetamine: evaluation of d- and l-isomers as releasing agents and uptake inhibitors for 3H-dopamine and 3H-norepinephrine in slices of rat neostriatum and cerebral cortex. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 194:47–56

Herzig V, Schmidt WJ (2004) Effects of MPEP on locomotion, sensitization and conditioned reward induced by cocaine or morphine. Neuropharmacology 47:973–984

Hyman SE, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ (2006) Neural mechanisms of addiction: the role of reward-related learning and memory. Annu Rev Neurosci 29:565–598

Jeziorski M, White FJ (1995) Dopamine receptor antagonists prevent expression, but not development, of morphine sensitization. Eur J Pharmacol 275:235–244

Jeziorski M, White FJ, Wolf ME (1994) MK-801 prevents the development of behavioral sensitization during repeated morphine administration. Synapse 16:137–147

Kalivas PW (2009) The glutamate homeostasis hypothesis of addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci 10:561–572

Kalivas PW, Duffy P (1998) Repeated cocaine administration alters extracellular glutamate in the ventral tegmental area. J Neurochem 70:1497–1502

Kelley AE (2004) Memory and addiction: shared neural circuitry and molecular mechanisms. Neuron 44:161–179

Kenny PJ, Boutrel B, Gasparini F, Koob GF, Markou A (2005) Metabotropic glutamate 5 receptor blockade may attenuate cocaine self-administration by decreasing brain reward function in rats. Psychopharmacology 179:247–254

Kenny PJ, Markou A (2004) The ups and downs of addiction: role of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci 25:265–272

Kew JN, Kemp JA (2005) Ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptor structure and pharmacology. Psychopharmacology 179:4–29

Koob GF, Sanna PP, Bloom FE (1998) Neuroscience of addiction. Neuron 21:467–476

Kotlinska J, Bochenski M (2007) Comparison of the effects of mGluR1 and mGluR5 antagonists on the expression of behavioral sensitization to the locomotor effect of morphine and the morphine withdrawal jumping in mice. Eur J Pharmacol 558:113–118

Kotlinska J, Bochenski M (2009) Pretreatment with group I metabotropic glutamate receptors antagonists attenuates lethality induced by acute cocaine overdose and expression of sensitization to hyperlocomotor effect of cocaine in mice. Neurotox Res. doi:10.1007/s12640-009-9136-8

Kuribara H (1995) Modification of cocaine sensitization by dopamine D1 and D2 receptor antagonists in terms of ambulation in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 51:799–805

Leone P, Di Chiara G (1987) Blockade of D-1 receptors by SCH 23390 antagonizes morphine- and amphetamine-induced place preference conditioning. Eur J Pharmacol 135:251–254

Mackey WB, van der Kooy D (1985) Neuroleptics block the positive reinforcing effects of amphetamine but not of morphine as measured by place conditioning. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 22:101–105

Maldonado C, Rodriguez-Arias M, Castillo A, Aguilar MA, Minarro J (2007) Effect of memantine and CNQX in the acquisition, expression and reinstatement of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 31:932–939

Maldonado R, Valverde O, Berrendero F (2006) Involvement of the endocannabinoid system in drug addiction. Trends Neurosci 29:225–232

Manzanedo C, Aguilar MA, Rodriguez-Arias M, Minarro J (2001) Effects of dopamine antagonists with different receptor blockade profiles on morphine-induced place preference in male mice. Behav Brain Res 121:189–197

Martin-Fardon R, Baptista MA, Dayas CV, Weiss F (2009) Dissociation of the effects of MTEP [3-[(2-methyl-1,3-thiazol-4-yl)ethynyl]piperidine] on conditioned reinstatement and reinforcement: comparison between cocaine and a conventional reinforcer. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 329:1084–1090

Mattingly BA, Hart TC, Lim K, Perkins C (1994) Selective antagonism of dopamine D1 and D2 receptors does not block the development of behavioral sensitization to cocaine. Psychopharmacology 114:239–242

McGeehan AJ, Janak PH, Olive MF (2004) Effect of the mGluR5 antagonist 6-methyl-2-(phenylethynyl)pyridine (MPEP) on the acute locomotor stimulant properties of cocaine, d-amphetamine, and the dopamine reuptake inhibitor GBR12909 in mice. Psychopharmacology 174:266–273

McGeehan AJ, Olive MF (2003) The mGluR5 antagonist MPEP reduces the conditioned rewarding effects of cocaine but not other drugs of abuse. Synapse 47:240–242

McKee BL, Meshul CK (2005) Time-dependent changes in extracellular glutamate in the rat dorsolateral striatum following a single cocaine injection. Neuroscience 133:605–613

Nagel J, Greco S, Klein K-U, Eilbacher B, Valastro B, Tober C, Danysz W (2007) Microdialysis reveals different brain PK of the selective mGluR5 negative modulators MTEP and MPEP. Soc Neurosci Abs 711.19

Naie K, Manahan-Vaughan D (2004) Regulation by metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 of LTP in the dentate gyrus of freely moving rats: relevance for learning and memory formation. Cereb Cortex 14:189–198

Nazarian A, Russo SJ, Festa ED, Kraish M, Quinones-Jenab V (2004) The role of D1 and D2 receptors in the cocaine conditioned place preference of male and female rats. Brain Res Bull 63:295–299

O'Leary DM, Movsesyan V, Vicini S, Faden AI (2000) Selective mGluR5 antagonists MPEP and SIB-1893 decrease NMDA or glutamate-mediated neuronal toxicity through actions that reflect NMDA receptor antagonism. Br J Pharmacol 131:1429–1437

Olive MF, McGeehan AJ, Kinder JR, McMahon T, Hodge CW, Janak PH, Messing RO (2005) The mGluR5 antagonist 6-methyl-2-(phenylethynyl)pyridine decreases ethanol consumption via a protein kinase C epsilon-dependent mechanism. Mol Pharmacol 67:349–355

Paterson NE, Markou A (2005) The metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 antagonist MPEP decreased break points for nicotine, cocaine and food in rats. Psychopharmacology 179:255–261

Paterson NE, Semenova S, Gasparini F, Markou A (2003) The mGluR5 antagonist MPEP decreased nicotine self-administration in rats and mice. Psychopharmacology 167:257–264

Pierce RC, Bell K, Duffy P, Kalivas PW (1996) Repeated cocaine augments excitatory amino acid transmission in the nucleus accumbens only in rats having developed behavioral sensitization. J Neurosci 16:1550–1560

Pierce RC, Kumaresan V (2006) The mesolimbic dopamine system: the final common pathway for the reinforcing effect of drugs of abuse? Neurosci Biobehav Rev 30:215–238

Popik P, Wrobel M (2002) Morphine conditioned reward is inhibited by MPEP, the mGluR5 antagonist. Neuropharmacology 43:1210–1217

Ranaldi R, Munn E, Neklesa T, Wise RA (2000) Morphine and amphetamine sensitization in rats demonstrated under moderate- and high-dose NMDA receptor blockade with MK-801 (dizocilpine). Psychopharmacology 151:192–201

Reid MS, Berger SP (1996) Evidence for sensitization of cocaine-induced nucleus accumbens glutamate release. NeuroReport 7:1325–1329

Reid MS, Hsu K Jr, Berger SP (1997) Cocaine and amphetamine preferentially stimulate glutamate release in the limbic system: studies on the involvement of dopamine. Synapse 27:95–105

Renoldi G, Calcagno E, Borsini F, Invernizzi RW (2007) Stimulation of group I mGlu receptors in the ventrotegmental area enhances extracellular dopamine in the rat medial prefrontal cortex. J Neurochem 100:1658–1666

Ritz MC, Lamb RJ, Goldberg SR, Kuhar MJ (1987) Cocaine receptors on dopamine transporters are related to self-administration of cocaine. Science 237:1219–1223

Robbe D, Kopf M, Remaury A, Bockaert J, Manzoni OJ (2002) Endogenous cannabinoids mediate long-term synaptic depression in the nucleus accumbens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:8384–8388

Robinson TE, Berridge KC (1993) The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Res Rev 18:247–291

Robinson TE, Berridge KC (2003) Addiction. Annu Rev Psychol 54:25–53

Rodrigues SM, Bauer EP, Farb CR, Schafe GE, LeDoux JE (2002) The group I metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR5 is required for fear memory formation and long-term potentiation in the lateral amygdala. J Neurosci 22:5219–5229

Rutten K, van der Kam EL, De Vry J, Bruckmann W, Tzschentke TM (2010) The mGluR5 antagonist 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)-pyridine (MPEP) potentiates conditioned place preference induced by various addictive and non-addictive drugs in rats. Addict Biol. doi:10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00235.x

Scheggi S, Mangiavacchi S, Masi F, Gambarana C, Tagliamonte A, De Montis MG (2002) Dizocilpine infusion has a different effect in the development of morphine and cocaine sensitization: behavioral and neurochemical aspects. Neuroscience 109:267–274

Schmidt HD, Pierce RC (2010) Cocaine-induced neuroadaptations in glutamate transmission: potential therapeutic targets for craving and addiction. Ann NY Acad Sci 1187:35–75

Schroeder JP, Overstreet DH, Hodge CW (2005) The mGluR5 antagonist MPEP decreases operant ethanol self-administration during maintenance and after repeated alcohol deprivations in alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Psychopharmacology 179:262–270

Sepulveda MJ, Hernandez L, Rada P, Tucci S, Contreras E (1998) Effect of precipitated withdrawal on extracellular glutamate and aspartate in the nucleus accumbens of chronically morphine-treated rats: an in vivo microdialysis study. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 60:255–262

Sevostianova N, Danysz W (2006) Analgesic effects of mGlu1 and mGlu5 receptor antagonists in the rat formalin test. Neuropharmacology 51:623–630

Shippenberg TS, Heidbreder C (1995) Sensitization to the conditioned rewarding effects of cocaine: pharmacological and temporal characteristics. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 273:808–815

Shippenberg TS, Herz A (1988) Motivational effects of opioids: influence of D-1 versus D-2 receptor antagonists. Eur J Pharmacol 151:233–242

Smith JA, Mo Q, Guo H, Kunko PM, Robinson SE (1995) Cocaine increases extraneuronal levels of aspartate and glutamate in the nucleus accumbens. Brain Res 683:264–269

Solinas M, Goldberg SR, Piomelli D (2008) The endocannabinoid system in brain reward processes. Br J Pharmacol 154:369–383

Spooren W, Ballard T, Gasparini F, Amalric M, Mutel V, Schreiber R (2003) Insight into the function of Group I and Group II metabotropic glutamate (mGlu) receptors: behavioural characterization and implications for the treatment of CNS disorders. Behav Pharmacol 14:257–277

Spyraki C, Fibiger HC, Phillips AG (1982) Cocaine-induced place preference conditioning: lack of effects of neuroleptics and 6-hydroxydopamine lesions. Brain Res 253:195–203

Stewart J, Badiani A (1993) Tolerance and sensitization to the behavioral effects of drugs. Behav Pharmacol 4:289–312

Tessari M, Pilla M, Andreoli M, Hutcheson DM, Heidbreder CA (2004) Antagonism at metabotropic glutamate 5 receptors inhibits nicotine- and cocaine-taking behaviours and prevents nicotine-triggered relapse to nicotine-seeking. Eur J Pharmacol 499:121–133

Tzschentke TM (2002) Glutamatergic mechanisms in different disease states: overview and therapeutical implications - an introduction. Amino Acids 23:147–152

Tzschentke TM (2007) Measuring reward with the conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm: update of the last decade. Addict Biol 12:227–462

Tzschentke TM, Schmidt WJ (1995) N-methyl-d-aspartic acid–receptor antagonists block morphine-induced conditioned place preference in rats. Neurosci Lett 193:37–40

Tzschentke TM, Schmidt WJ (1996) Procedural examination of behavioural sensitisation to morphine: lack of blockade by MK-801, occurrence of sensitised sniffing, and evidence for cross-sensitisation between morphine and MK-801. Behav Pharmacol 7:169–184

Tzschentke TM, Schmidt WJ (1997) Interactions of MK-801 and GYKI 52466 with morphine and amphetamine in place preference conditioning and behavioural sensitization. Behav Brain Res 84:99–107

van der Kam EL, de Vry J, Tzschentke TM (2007) Effect of 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl) pyridine on intravenous self-administration of ketamine and heroin in the rat. Behav Pharmacol 18:717–724

van der Kam EL, de Vry J, Tzschentke TM (2009a) 2-Methyl-6(phenylethynyl)-pyridine (MPEP) potentiates ketamine and heroin reward as assessed by acquisition, extinction, and reinstatement of conditioned place preference in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol 606:94–101

van der Kam EL, de Vry J, Tzschentke TM (2009b) The mGlu5 receptor antagonist 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)pyridine (MPEP) supports intravenous self-administration and induces conditioned place preference in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol 607:114–120

van Ree JM, Gerrits MAFM, Vanderschuren LJMJ (1999) Opioids, reward and addiction: an encounter of biology, psychology, and medicine. Pharmacol Rev 51:341–396

Vanderschuren LJMJ, Kalivas PW (2000) Alterations in dopaminergic and glutamatergic transmission in the induction and expression of behavioral sensitization: a critical review of preclinical studies. Psychopharmacology 151:99–120

Vanderschuren LJMJ, Schoffelmeer ANM, De Vries TJ (1997) Does dizocilpine (MK-801) inhibit the development of morphine-induced behavioural sensitization in rats? Life Sci 61:PL427–PL433

Vanderschuren LJMJ, Schoffelmeer ANM, Mulder AH, De Vries TJ (1998) Dizocilpine (MK801): use or abuse? Trends Pharmacol Sci 19:79–81

Vanderschuren LJMJ, Pierce RC (2010) Sensitization processes in drug addiction. In: Self DW, Staley JK (eds) Behavioral neuroscience of drug addiction. Current topics in behavioral neurosciences 3. Springer, New York, pp 179–195

Vezina P, Stewart J (1989) The effect of dopamine receptor blockade on the development of sensitization to the locomotor activating effects of amphetamine and morphine. Brain Res 499:108–120

White FJ, Joshi A, Koeltzow TE, Hu XT (1998) Dopamine receptor antagonists fail to prevent induction of cocaine sensitization. Neuropsychopharmacology 18:26–40

Wise RA (2004) Dopamine, learning and motivation. Nat Rev Neurosci 5:483–494

Wolf ME (1998) The role of excitatory amino acids in behavioral sensitization to psychomotor stimulants. Prog Neurobiol 54:679–720

Wolf ME, Jeziorski M (1993) Coadministration of MK-801 with amphetamine, cocaine or morphine prevents rather than transiently masks the development of behavioral sensitization. Brain Res 613:291–294

Xu J, Zhu Y, Contractor A, Heinemann SF (2009) mGluR5 has a critical role in inhibitory learning. J Neurosci 29:3676–3684

Acknowledgements

We thank Viviana Trezza for assistance.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Veeneman, M.M.J., Boleij, H., Broekhoven, M.H. et al. Dissociable roles of mGlu5 and dopamine receptors in the rewarding and sensitizing properties of morphine and cocaine. Psychopharmacology 214, 863–876 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-010-2095-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-010-2095-1