Abstract

Background

Stimuli from the terminal phase of smoke or drug intake are paired with drug effect but have surprisingly low cue reactivity. Smoking terminal stimuli were compared to cues under conditions of different perceived smoke intake to probe whether (1) terminal stimuli are only weak cues, (2) any effect is an artifact of rigid test conditions, and (3) terminal stimuli have a unique function during the intake ritual.

Materials and methods

Nonabstinent, healthy smokers were tested in three experiments with one-session, within-subject cue reactivity tests. Smoking terminal stimuli and cues were compared using pictures depicting events after completion (END) and before start of smoke inhalation (BEGIN). Test pictures were presented alone and in combination with no-go symbols (from no-smoking signs) or with extra cues to decrease and to increase perceived smoke availability, respectively. Measured were subjective effects and affect modulation of the startle reflex.

Results

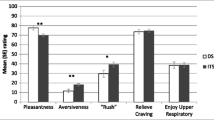

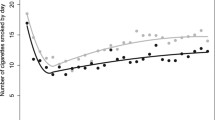

END stimuli relative to BEGIN stimuli evoked less subjective craving and pleasure but more arousal. A no-go stimulus, which reduced reports of intention to smoke, reduced the reactivity to BEGIN but only marginally affected responses to END stimuli. This was confirmed with different sets of test pictures and using tests with the startle response. An extra cue did not affect reactivity to a BEGIN stimulus but increased craving and pleasure to the END stimulus, although not to the level of BEGIN stimuli alone.

Conclusions

This first systematic study of terminal stimuli found their effects to be robust and have test generality. They are probably not weak cues but evoke reactivity, which may oppose reactivity of cues. They may signal poor availability of drug. Methodological, clinical, and theoretical implications were noted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The word “cues” specifically means those drug stimuli leading to craving for drug and/or its self-administration. This reflects a use in the drug abuse literature and is not to be confused with its common use as a synonym for conditioned or discriminative stimuli. Our labeling was necessary to set apart cues and cue reactivity from terminal stimuli and their effects. Like cues, terminal stimuli may also acquire their meaning through pairing with drug effect. Hence, we wanted to avoid any confusion arising from the fact that both cues and terminal stimuli may be drug-paired but have different effects on craving. Cues were modeled here by BEGIN and terminal stimuli by END smoking stimuli, respectively; these terms may be used interchangeably.

The END smoking stimuli in Experiment 1 were B6, B12, B16, B19, B22, B23, B28, and B31 from Experiment 1 of Mucha et al. (1999). The BEGIN stimuli we used were B1, B5, B10, B11, B18, and B20 from Experiment 1 of Mucha et al. (1999) and two pictures (C1 and C2) prepared during the generation of pictures for Experiment 2 of Mucha et al. (1999). They are pictures found in an unpublished battery of pictures (Mucha and Pauli unpublished).

The smoking pictures in Experiment 2 were the images A2, A4, A6, A10 A14, A16, A18, and A20 as END stimuli and A1, A3, A5, A9 A13, A15, A17, and A19 as BEGIN stimuli found in Mucha and Pauli (unpublished) and were used in Exp. 2 of Mucha et al. (1999).

The nonsmoking, emotional pictures were derived from the following individual images of the International Affective Picture System (Lang et al. 1996). They comprised neutral (2840, 5534, 6150, 7000, 7002, 7050, 7190, 7820), unpleasant (3170, 3530, 6230, 9410, 3000, 3150, 3010, 3102) and pleasant objects or scenes (4660, 8030, 8080, 8370, 8380, 5480, 4490, 4510, 4180, and 4290).

The smoking pictures in Experiment 3 were the images from Experiment 2 together with two additional BEGIN (A7, A11) and END images (A8, A12) generated at the same time; they are to be found in Mucha and Pauli (unpublished).

References

Anastasi A (1990) Psychological testing, 6th edn. Macmillan, New York

Anderson NH (1968) Application of a linear-serial model to a personality-impression task using serial presentation. J Personal Social Psychol 10:354s–362s

Benowitz NL (1990) Clinical pharmacology of inhaled drugs of abuse: implications in understanding nicotine dependence. NIDA Res Monogr 99:12–29

Bevins RA, Palmatier MI (2004) Extending the role of associative learning processes in nicotine addiction. Behav Cog Neurosc Rev 3:143–158

Bouton M (2007) Learning and behavior: a contemporary synthesis. Sinauer, Sunderland

Bouton ME, Mineka S, Barlow DH (2001) A modern learning theory perspective on the etiology of panic disorder. Psych Rev 108:4–32

Bushnell PJ, Levin ED, Marrocco RT, Sarter MF, Strupp BJ, Warburton DM (2000) Attention as a target of intoxication: insights and methods from studies of drug abuse. Neurotox Teratol 22:487–502

Carter BL, Tiffany ST (2001) The cue-availability paradigm: the effects of cigarette availability on cue reactivity in smokers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 9:183–190

Carter BL, Robinson JD, Lam CY, Wetter DW, Tsan JY, Day SX, Cinciripini PM (2006) A psychometric evaluation of cigarette stimuli used in a cue reactivity study. Nic Tobac Res 8:361–369

Clarke PBS (1987) Nicotine and smoking: a perspective from animal studies. Psychopharmacology 92:135–143

Conklin CA (2006) Environments as cues to smoke: implications for human extinction-based research and treatment. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 14:12–19

Cunningham CL (1998) Drug conditioning and drug-seeking behavior. In: O’Donohue W (ed) Learning and behavior therapy. Allyn and Bacon, Boston

Davis M (1979) Diazepam and flurazepam: effects on conditioned fear as measured with the potentiated startle paradigm. Psychopharmacol 62:1–7

Dempsey JP, Cohen LM, Hobson VL, Randall (2007) Appetitive nature of cues re-confirmed with physiological measures and the potential role of stage of change. Psychpharmacol 194:253–250

Droungas A, Ehrman RN, Childress AR, O’Brien CP (1995) Effect of smoking cues and cigarette availability on craving and smoking behavior. Addict Behav 20:657–673

Ehrman RN, Robbins SJ, Bromwell MA, Lankford ME, Monterosso JR, O’Brien CP (2002) Comparing attentional bias to smoking cues in current smokers, former smokers, and non-smokers using a dot-probe task. Drug Alc Depend 67:185–191

Eikelboom R, Stewart J (1982) Conditioning of drug-induced physiological responses. Psych Rev 89:507–528

Fagerström KO (1978) Measuring degree of physical dependence to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment. Addict Behav 3:235–241

Fanselow MS (1994) Neural organization of the defensive behavior system responsible for fear. Psychon Bull Rev 1:429–438

Fendt M, Mucha RF (2001) Anxiogenic-like effects of opiate withdrawal seen in the fear-potentiated startle test, an interdisciplinary probe for drug-related motivational states. Psychopharmacol 155:242–250

Geier A, Mucha RF, Pauli P (2000) Appetitive nature of drug cues confirmed with physiological measures in a model using pictures of smoking. Psychopharmacol 150:283–291

Gilbert DG, Rabinovich NE (2002) ISIS: international smoking image series with neutral counterparts, v.1.2. Integrative Neuroscience Laboratory, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale

Gottschalk DH, Rist F, Gerlach AL, Mucha RF (2002) Ereigniskorrelierte Potentiale zu standardisierten rauchassoziierten Bildern. In: Richter G, Rommelspacher H, Spies C (eds) “Alkohol, Nikotin, Kokain… und kein Ende?”: Suchtforschung, Suchtmedizin und Suchttherapie am Beginn des neuen Jahrzehnts. Pabst Science, Berlin, p 520

Hinson RE, McKee SA, Lovenjak T, Wall AM (1993) The effect of the CS–UCS interval and extinction on place conditioning and analgesic tolerance with morphine. J Psychopharmacol 7:164–172

Hogan JA (1988) Cause and function in the development of behavior systems. In: Blass EM (ed) Handbook of behavioral neurobiology: developmental psychobiology and behavioral ecology. vol. 9. Plenum, New York, pp 63–106

Kalant H (1998) Selectivity of drug action. In: Kalant H, Roschlau W (eds) Principles of medical pharmacology. 6th edn. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 109–119

Kearns DN, Weiss SJ, Schindler CW, Panlilio LV (2005) Conditioned inhibition of cocaine seeking in rats. J Exp Psychol Anim Beh Process 31:247–253

Kirk RE (1995) Experimental design: procedures for the behavioral sciences, 3rd edn. Brooks/Cole, Pacific Grove

Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN (1990) Emotion, attention, and the startle reflex. Psychol Rev 97:337–395

Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN (1996) The International affective picture system. NIMH Center for the study of Emotion and Attention, University of Florida, Gainesville

Mackintosh NJ (1974) The psychology of animal learning. Academic, London

McNally GP, Akil H (2001) Effects of contextual or olfactory cues previously paired with morphine withdrawal on behavior and pain sensitivity in the rat. Psychopharmacol 156:381–387

Mook DG (1988) On the organization of satiety. Appetite 11:27–39

Mucha RF (1991) What is learned during opiate withdrawal conditioning? Evidence for a cue avoidance model. Psychopharmacol 104:391–396

Mucha RF, Herz A (1986) Preference conditioning produced by opioid active and inactive isomers of levorphanol and morphine in rat. Life Sci 38:241–249

Mucha RF, Volkovskis C, Kalant H (1981) Conditioned increases in locomotor activity produced with morphine as an unconditioned stimulus, and the relation of conditioning to acute morphine effect and tolerance. J Comp Physiol Psych 95:351–362

Mucha RF, Geier A, Pauli P (1999) Modulation of craving by cues having differential overlap with pharmacological effect: evidence for cue approach in smokers and social drinkers. Psychopharmacol 147:306–313

Mucha RF, Geier A, Stühlinger M, Mundle G (2000) Appetitive effects of drug cues modeled by pictures of the intake ritual: generality of cue-modulated startle examined with inpatient alcoholics. Psychopharmacol 151:428–432

Mucha RF, Pauli P, Weyers P (2006) Psychophysiology and implicit cognition in drug use: significance and measurement of motivation for drug use with emphasis on startle tests. In: Wiers RW, Stacey AW (eds) Handbook of implicit cognition and addiction. Sage, Thousand Oaks, pp 201–214

Pauli P, Bourne LE, Birbaumer N (1998) Extensive practice in mental arithmetic and practice transfer over a ten-month retention interval. Math Cognit 4:21–46

Pearce JM (1997) Animal learning and cognition, 2nd edn. Psychology Press, Hove

Poulos CX, Cappell H (1991) Homeostatic theory of drug tolerance: a general model of physiological adaptation. Psych Rev 98:390–408

Rescorla RA (1969) Pavlovian conditioned inhibition. Psych Bull 72:77–94

Robinson TE, Berridge KC (1993) The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Res Rev 18:247–291

Rose JE, Behm FM, Westman EC, Coleman RE (1999) Arterial nicotine kinetics during cigarette smoking and intravenous nicotine administration: implications for addiction. Drug Alc Depend 56:99–107

Röskam S, Koch M (2006) Enhanced prepulse inhibition of startle using salient prepulses in rats. Int J Psychophysiol 60:10–14

Sidman M (1960) Tactics of scientific research. Evaluating experimental data in psychology. Basic Books, New York

Siegel A (1967) Stimulus generalization of a classically conditioned response along a temporal dimension. J Comp Physiol Psych 64:461–466

Siegel S, Ramos BMC (2002) Applying laboratory research: drug anticipation and the treatment of drug addiction. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 10:162–183

Spetch ML, Wilkie DM, Pinel JP (1981) Backward conditioning: a reevaluation of the empirical evidence. Psych Bull 89:163–175

Stewart J, de Wit H, Eikelboom R (1984) Role of unconditioned and conditioned drug effects in the self-administration of opiates and stimulants. Psych Rev 91:251–268

Thibaut J, Dupont M, Aselme P (2001) Dissociations between categorization and similarity judgments as a result of learning feature distributions. Mem Cognit 30:647–656

Tiffany ST (1990) A cognitive model of drug urges and drug-use behavior: role of automatic and nonautomatic processes. Physiol Rev 97:147–168

Timberlake W (1997) An animal-centered, causal-system approach to the understanding and control of behavior. Appl Anim Behav Sci 53:107–129

Tinsley MR, Timberlake W, Sitomer M, Widman DR (2002) Conditioned inhibitory effects of discriminated Pavlovian training with food in rats depend on interactions of search modes, related repertoires, and response measures. Anim Learn Behav 30:217–227

White NM (1996) Addictive drugs as reinforcers: multiple partial actions on memory systems. Addict 91:921–949

Wiers RW, Stacey AW (2006) Implicit cognition and addiction: an introduction. In: Wiers RW, Stacey AW (eds) Handbook of implicit cognition and addiction. Sage, Thousand Oaks, pp 1–8

Acknowledgements

The paper is dedicated to Harold Kalant on his 85th birthday, a pioneer in the research on the behavioral and psychological mechanisms of phenomena underlying drug dependence. The authors are grateful to E. Wahlen, V. Roeder, and S. Wenkel for technical and secretarial assistance. Dr. J. Hogan was helpful in dealing with the ideas behind behavior systems and Dr. H. Kalant in commenting on the manuscript. Some of the data were submitted by M. Weber to the University of Tübingen as partial fulfillment of a thesis supervised by M. Hautzinger and R. Mucha. The experimental work was supported in part by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG). Support for M. Winkler came from the Würzburg DFG Research Group FOR605 “Emotion and behavior: reflective and impulsive processes.” The present study was conceived and implemented without any conflict of interest. The principal author (RFM) acknowledges that since then he has invested in a venture to market pictures of the end of smoking to symbolize smoking with little craving.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mucha, R.F., Pauli, P., Weber, M. et al. Smoking stimuli from the terminal phase of cigarette consumption may not be cues for smoking in healthy smokers. Psychopharmacology 201, 81–95 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-008-1249-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-008-1249-x