Abstract

Summary

This phase 2 study evaluated the efficacy and safety of transitioning to zoledronate following romosozumab treatment in postmenopausal women with low bone mass. A single dose of 5 mg zoledronate generally maintained the robust BMD gains accrued with romosozumab treatment and was well tolerated.

Introduction

Follow-on therapy with an antiresorptive agent is necessary to maintain the skeletal benefits of romosozumab therapy. We evaluated the use of zoledronate following romosozumab treatment.

Methods

This phase 2, dose-finding study enrolled postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density (BMD). Subjects who received various romosozumab doses or placebo from months 0–24 were rerandomized to denosumab (60 mg SC Q6M) or placebo for 12 months, followed by open-label romosozumab (210 mg QM) for 12 months. At month 48, subjects who had received active treatment for 48 months were assigned to no further active treatment and all other subjects were assigned to zoledronate 5 mg IV. Efficacy (BMD, P1NP, and β-CTX) and safety were evaluated for 24 months, up to month 72.

Results

A total of 141 subjects entered the month 48–72 period, with 51 in the no further active treatment group and 90 in the zoledronate group. In subjects receiving no further active treatment, lumbar spine (LS) BMD decreased by 10.8% from months 48–72 but remained 4.2% above the original baseline. In subjects receiving zoledronate, LS BMD was maintained (percentage changes: − 0.8% from months 48–72; 12.8% from months 0–72). Similar patterns were observed for proximal femur BMD in both groups. With no further active treatment, P1NP and β-CTX decreased but remained above baseline at month 72. Following zoledronate, P1NP and β-CTX levels initially decreased but approached baseline by month 72. No new safety signals were observed.

Conclusion

A zoledronate follow-on regimen can maintain robust BMD gains achieved with romosozumab treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a chronic condition requiring long-term therapy, potentially involving sequential treatment regimens with different agents over a patient’s lifetime. Accumulating evidence supports treatment strategies that improve and then maintain bone mineral density (BMD) to desired goals, in order to reduce fracture risk [1,2,3,4].

Antiresorptive drugs such as bisphosphonates and denosumab may be given for several years. These agents increase BMD but do not correct the deficits in trabecular microarchitecture [5, 6]. Notably, therapies that stimulate bone formation can quickly increase BMD and improve bone structure [7]. Regulatory recommendations limit the use of previously available anabolic agents, including the parathyroid hormone (PTH) analogue teriparatide and the PTH receptor agonist abaloparatide, to a combined 2 years of treatment in a patient’s lifetime [8, 9]; thus, limiting the use of these drugs for long-term management of osteoporosis. Additionally, the BMD gains achieved with teriparatide are lost upon discontinuing therapy, but these gains can be preserved or amplified when subjects are switched to alendronate or denosumab upon stopping teriparatide therapy [10, 11]. Similarly, BMD gains and fracture risk reduction observed with abaloparatide are maintained upon transitioning to alendronate [12]. As a result, current guidelines recommend following anabolic therapy with a potent antiresorptive agent [13, 14].

Romosozumab is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits sclerostin and has a dual effect of increasing bone formation and decreasing bone resorption [15,16,17], and has also been shown to improve skeletal microarchitecture [18, 19]. In the first 24 months of this dose-finding phase 2 study in postmenopausal women with low bone mass, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of different romosozumab doses (70 mg, 140 mg, and 210 mg) administered by subcutaneous (SC) injection at 1- or 3-month intervals to identify the optimal romosozumab regimen [17, 20]. Treatment with romosozumab 210 mg monthly (QM) for 12 months was subsequently shown to significantly increase BMD and reduce fracture risk compared to placebo and to alendronate in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis in phase 3 studies [21, 22]. The fracture protection benefit of romosozumab was maintained during the subsequent interval of antiresorptive treatment. A phase 3 open-label study also demonstrated the efficacy and safety of romosozumab when administered to subjects previously treated with bisphosphonates [23]. Romosozumab has been approved in several countries, e.g., for the treatment of osteoporosis in the USA [24] and for the treatment of severe osteoporosis in the EU [25] in postmenopausal women at high risk for fracture.

We extended the current phase 2 study to investigate the effects of discontinuing romosozumab and switching to denosumab or placebo from months 24 to 36, observing that subjects receiving denosumab continued to accrue BMD, whereas BMD returned toward baseline levels when romosozumab was discontinued without follow-on therapy [20]. These data pointed to the need for antiresorptive follow-on therapy to maintain the large and rapid BMD gains from romosozumab treatment. Phase 3 studies have subsequently confirmed the efficacy of antiresorptive therapy such as denosumab or alendronate following romosozumab in both maintaining BMD and in preserving the benefit of the initial treatment with romosozumab on fracture risk [2, 21, 22].

In a prior extension of this phase 2 study, subjects received a second course of romosozumab 210 mg QM from months 36 to 48. Rapid and large BMD gains with romosozumab were observed in subjects who had received no active treatment in the 12 months prior [26]. The BMD response to romosozumab following denosumab was very small, but romosozumab prevented BMD declines following denosumab discontinuation. Recognizing the need for following romosozumab therapy with an antiresorptive agent, in the last stage of this phase 2 study, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of a single dose of zoledronate (also known as zoledronic acid) 5 mg upon stopping treatment with the second course of romosozumab. This report describes the results of this final segment of the study.

Materials and methods

Study design

This phase 2, international, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-finding, parallel-group study enrolled postmenopausal women aged 55 to 85 years with a low BMD (T-score of ≤ − 2.0 and ≥ − 3.5 at the lumbar spine, total hip, or femoral neck) [17]. Key exclusion criteria have been previously described [17] and are provided in Online Resource Supplemental Methods.

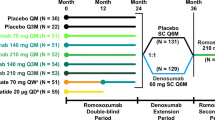

Treatment groups in the romosozumab double-blind period (months 0 to 24), denosumab extension period (months 24 to 36), romosozumab second-course period (months 36 to 48), and zoledronate follow-on period (months 48 to 72) are presented in Fig. 1; additional details of the study design have been previously published [17]. Briefly, women were randomized to receive 1 of 5 dosing regimens of SC romosozumab or to receive 1 of 2 open-label comparators (oral alendronate 70 mg weekly [QW] or SC teriparatide 20 μg daily) (Fig. 1a). The remaining 52 women were randomly assigned to receive placebo injections QM or Q3M.

Study schema. a Subjects were randomized 1:1:1:1:1:1:1:1 to the first 24 months of treatment. Administration of placebo and the various romosozumab doses was blinded; alendronate and teriparatide were administered open-label. At month 24, subjects were rerandomized (1:1) within treatment group to placebo or denosumab (60 mg SC Q6M) for 12 months, followed by a 12-month second course of romosozumab 210 mg QM. b For subjects who reached month 48 of the study, eligibility for the month 48 to 72 zoledronate follow-on period was assessed by the investigator using a 3-step approach with no randomization. Subjects were assigned to no further active treatment if they (1) had been assigned to active treatment throughout the first 48 months (romosozumab any dose and schedule, followed by denosumab 60 mg Q6M, and then followed by romosozumab 210 mg QM); (2) had no clinical vertebral or fragility fracture between months 24 and 48; (3) had a BMD T-score > − 2.5 at the lumbar spine, total hip, or femoral neck at month 48; or (4) had any contraindication to zoledronate. All other subjects were assigned to receive a single IV dose of zoledronate 5 mg. aSubjects transitioned to romosozumab 140 mg QM at month 12, were randomized in the denosumab extension period, completed the study at month 36, and are not included in the present analysis. bSubjects completed the study at month 12 and are not included in the present analysis. cOf the subjects randomized to romosozumab 210 mg QM in the double-blind period, 12 entered the no further active treatment group and 17 entered the zoledronate group during the follow-on phase. IV intravenous, PO orally, QD every day, QM every month, Q3M every 3 months, QW every week, SC subcutaneous

On completing the 12-month double-blind treatment period, subjects in the romosozumab and placebo groups continued their assigned treatment for an additional 12 months [17, 20] (Fig. 1a). At month 24, eligible consenting subjects entered a 12-month extension phase and were rerandomized (1:1) to double-blind treatment with placebo or denosumab 60 mg (Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA) every 6 months (Q6M) (Fig. 1a). Subjects who completed the month 24 to 36 denosumab extension period entered a 12-month phase where they received open-label romosozumab 210 mg (Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA) QM through month 48 (romosozumab second-course period).

Subjects who completed the month 36 to 48 romosozumab second-course period were then eligible to enter a 24-month extension (month 48 to 72 follow-on period) where they were assigned to either no further active treatment or to receive a single intravenous (IV) dose of zoledronate 5 mg at month 48 (Fig. 1a, b). Eligibility for the month 48 to 72 follow-on period was assessed by the investigator using a 3-step approach with no randomization. Subjects were assigned to no further active treatment if they (1) had been assigned to active treatment (romosozumab any dose and schedule, followed by denosumab 60 mg Q6M, and then followed by romosozumab 210 mg QM) throughout the first 48 months; (2) had no clinical vertebral or fragility fracture between months 24 and 48; (3) had a BMD T-score > − 2.5 at the lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck at month 48; or (4) had any contraindication to zoledronate. All other subjects were assigned to zoledronate which was administered at month 48, approximately 4 weeks after the month 47 dose of romosozumab.

The study protocol was approved by an independent ethics committee or institutional review board at each center, and the study was registered as a clinical trial with registration identification ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00896532. The study was conducted in accordance with International Conference on Harmonization guidelines on Good Clinical Practice and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All subjects provided written informed consent.

Study procedures

The study procedures for assessing BMD, bone turnover markers, and other measures during the first 48 months of the study have been previously published [17, 20]. This report describes BMD measured at the lumbar spine and proximal femur by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (Lunar, GE Medical Systems, Madison, WI, USA or Hologic, Hologic Inc., Bedford, MA, USA) at months 36, 39, 42, 48, 54, 60, 66, and 72. BioClinica (previously known as Synarc; Newark, CA, USA) analyzed the scans and provided quality control of the scans and scanners. Blood was collected and analyzed for serum chemistry, hematology, bone turnover markers, and antiromosozumab antibodies. Levels of the bone formation marker procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide (P1NP; UniQ P1NP RIA, Orion Diagnostica Oy, Espoo, Finland) and the bone resorption marker β-isomer of the C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (β-CTX; Serum CrossLaps ELISA, Nordic Bioscience Diagnostics, A/S, Herlev, Denmark) were assessed at months 36, 37, 39, 42, 45, 48, 51, 54, 60, 66, and 72. Serum levels of antiromosozumab antibodies were assessed at months 36, 39, 42, 45, 48, and 51. Samples were tested for romosozumab neutralizing activity in vitro in subjects who tested positive for binding antibodies, as previously described [16]. Adverse events were collected as observed by the investigator or reported by subjects. Potential cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femoral fracture were adjudicated by independent committees.

Study outcomes

Results of the study periods up to month 48 have been previously published [17, 20, 26]. This report focuses on results from the month 48 to 72 follow-on period, assessing the exploratory endpoints of the percentage change in BMD at the lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck and bone turnover markers (P1NP and β-CTX), and the safety of transitioning to zoledronate after 12 months of treatment with a second course of romosozumab.

Statistical analysis

The efficacy set included subjects enrolled in the month 48 to 72 follow-on period, and data were analyzed according to the treatment allocation as determined by the assigned treatment sequence throughout the study. The safety set included all subjects who were enrolled in the month 48 to 72 follow-on period, and data were analyzed by treatment received rather than by treatment assigned.

Changes in BMD and bone turnover markers were summarized separately for subjects assigned to no further active treatment and subjects assigned to zoledronate. Subjects assigned to no further active treatment who began receiving an alternative treatment for osteoporosis, as determined by the investigator, were censored 3 months after the start of the alternative treatment for BMD and at the start of alternative treatment for bone turnover markers. All endpoints were summarized descriptively. Percentage change in BMD from month 48 at months 54, 60, 66, and 72 and from the initial baseline (month 0) at months 48, 54, 60, 66, and 72 are presented as means and 95% confidence intervals. Percentage change in P1NP and β-CTX from month 48 at months 51, 54, 60, 66, and 72 and from the initial baseline (month 0) at months 51, 54, 60, 66, and 72 are presented as medians and interquartile ranges.

Safety endpoints were summarized for subjects assigned to no further active treatment and subjects assigned to zoledronate using the safety analysis set for the month 48 to 72 follow-on period. For subjects assigned to no further active treatment, the start of the month 48 to 72 follow-on period was defined as the month 48 study visit, 4 weeks after the month 47 dose of romosozumab. All adverse events occurring on this date until the end of study date were reported in the follow-on period. For subjects assigned to zoledronate, the start of the month 48 to 72 follow-on period was defined as the date of the first dose of zoledronate. All adverse events that started on the day of the first dose of zoledronate or later were attributed to zoledronate and hence were reported in the follow-on period. Adverse events were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA; version 18.1).

Results

Subject disposition

Subject disposition has been previously published for the month 0 to 24 romosozumab double-blind period and the month 24 to 48 extension period [17, 20], and is summarized through month 72 in Online Resource Fig. S1 (which includes all the study phases). Of the 313 subjects randomized to placebo (n = 52) and romosozumab (n = 261) in the month 0 to 24 romosozumab double-blind period, 167 entered the month 36 to 48 romosozumab second-course period. Of those, 141 entered the month 48 to 72 zoledronate follow-on period. A total of 51 of the 141 subjects who entered the follow-on period met the eligibility criteria to be assigned to no further active treatment. These include 1 subject who received placebo in the month 0 to 24 romosozumab double-blind period and was incorrectly assigned to no further active treatment in the follow-on period and 4 subjects who were assigned to no further active treatment but received alendronate for the treatment of bone loss that developed during the follow-on period. The remaining 90 subjects were assigned to receive a single IV dose of zoledronate 5 mg at month 48. These include 2 subjects who were incorrectly assigned to receive zoledronate and 3 subjects who were assigned to zoledronate but did not receive investigational product from months 48 to 72. Of the 51 subjects assigned to no further active treatment, 50 (98.0%) completed the month 48 to 72 follow-on period and 1 died (Online Resource Fig. S1). Of the 90 subjects assigned to zoledronate, 88 (97.8%) completed the month 48 to 72 follow-on period and 2 (2.2%) discontinued the study (1 after the subject was determined to be ineligible; 1 after consent was withdrawn) (Online Resource Fig. S1). All subjects enrolled in the month 48 to 72 follow-on period were included in the safety analysis except for the 3 subjects assigned to zoledronate who did not receive the therapy.

Baseline characteristics

At the initial study baseline (month 0), demographic and key characteristics were well matched between subject groups entering the month 48 to 72 follow-on period (Table 1). At month 48, the baseline for the month 48 to 72 follow-on period reported here, subjects who had been on active treatment in the previous 48 months and were therefore assigned to no further active treatment in this follow-on period exhibited somewhat higher BMD T-score values and levels of both bone turnover markers than subjects assigned to zoledronate (Table 1). The differences in BMD T-score values and levels of both bone turnover markers between the groups might be due, in large part, to the difference in the therapies received between the two study groups during year 3 of the phase 2 study: the subjects assigned to no further active treatment had received denosumab during months 24 to 36 while almost all of the subjects in the zoledronate group had received placebo during that interval.

Efficacy

Bone mineral density

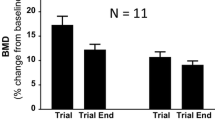

BMD results for the overall population entering the month 48 to 72 follow-on period are presented in Fig. 2 and Online Resource Table S1. In subjects assigned to no further active treatment (n = 51), lumbar spine BMD decreased from months 48 to 72 (percentage change [95% CI]: − 10.8% [− 12.1, − 9.5]), decreasing from a mean of 17.3% [15.2, 19.3] above initial baseline value at months 48 to 4.2% [2.3, 6.1]) above the initial baseline at month 72 (Fig. 2a, Online Resource Table S1). BMD gains at the total hip and femoral neck for this group were also reversed after romosozumab discontinuation. Total hip BMD decreased from months 48 to 72 (percentage change [95% CI]: − 6.4% [− 7.4, − 5.3]), and remained close to the initial baseline level at month 72 (percentage change [95% CI] from initial baseline: − 1.6% [− 2.8, − 0.3]) (Fig. 2b, Online Resource Table S1). Femoral neck BMD decreased from months 48 to 72 (percentage change [95% CI]: − 5.9% [− 7.2, − 4.7]), and remained close to the initial baseline level at month 72 (percentage change [95% CI] from initial baseline: − 1.2% [− 2.6, 0.2]) (Fig. 2c, Online Resource Table S1).

Percentage change in BMD at the lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck in all subjects who received romosozumab during months 36–48 and who were then assigned to no further active treatment (n = 51; a–c) or zoledronate (n = 90; d–f) from months 48 to 72. Data are mean (95% CI). BMD bone mineral density, CI confidence interval, DMAb denosumab, QM every month, Q6M every 6 months

In subjects assigned to zoledronate (n = 90), lumbar spine BMD was maintained through months 48 to 72 (percentage change [95% CI] from months 48 to 72: − 0.8% [− 1.6, 0]; percentage change [95% CI] from initial baseline to month 72: 12.8% [11.4, 14.3]) (Fig. 2d, Online Resource Table S1). Results for total hip and femoral neck also showed a similar pattern to results observed for the lumbar spine. Total hip BMD was maintained through months 48 to 72 (percentage change [95% CI] from month 48: 0.1% [− 0.5, 0.7]; percentage change [95% CI] from initial baseline to month 72: 4.2% [3.1, 5.3]) (Fig. 2e, Online Resource Table S1). Femoral neck BMD was maintained through months 48 to 72 (percentage change [95% CI] from month 48: 0.5% [− 0.4, 1.3]; percentage change [95% CI] from initial baseline to month 72: 4.4% [3.0, 5.8]) (Fig. 2f, Online Resource Table S1).

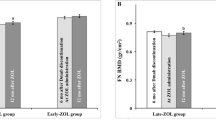

Bone turnover markers

P1NP and β-CTX results for the overall population entering the month 48 to 72 follow-on period are presented in Fig. 3 and Online Resource Table S2. In subjects assigned to no further active treatment from months 48 to 72 (n = 51), median P1NP initially decreased but stayed above the initial baseline level until month 72, and median β-CTX increased initially then gradually decreased but remained above the initial baseline level until month 72 (Fig. 3a, b, Online Resource Table S2). In subjects assigned to zoledronate from months 48 to 72 (n = 90), median P1NP and β-CTX levels decreased but then moved toward initial baseline level by month 72 (Fig. 3c, d, Online Resource Table S2).

Percentage change in P1NP and β-CTX in all subjects who received romosozumab during months 36–48 and who were then assigned to no further active treatment (n = 51; a, b) or zoledronate (n = 90; c, d) from months 48 to 72. Data are median (Q1, Q3). β-CTX β-isomer of the C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen, DMAb denosumab, IV intravenous, P1NP procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide, Q1 quartile 1, Q3 quartile 3, QM every month, Q6M every 6 months

Subgroup analysis

In the subpopulation of 29 subjects (no further active treatment [n = 12]; zoledronate [n = 17]) who received romosozumab 210 mg QM during the first 24 months of the study, changes in BMD and bone turnover markers during the month 48 to 72 follow-on period were consistent with changes observed in the overall population (data not shown).

Safety

A summary of adverse events reported from months 48 to 72 is provided in Table 2. No subject discontinued investigational product or study due to an adverse event. There were no deaths in the zoledronate group versus 1 death in the no further active treatment group. No adverse events of hypocalcemia, hyperostosis, clinical vertebral fractures, adjudicated osteonecrosis of the jaw, or adjudicated atypical femoral fracture were reported in either treatment group. Fractures occurred in 4 subjects in the no further active treatment group and 2 subjects in the zoledronate group. Additional details of the safety assessment from months 48 to 72 are presented in the Online Resource Supplemental Results: Additional Safety.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that a single 5 mg dose of zoledronate preserves BMD for up to 2 years after stopping romosozumab and provides further insights into the potential treatment sequence with romosozumab. Simply stopping romosozumab, even after very large BMD gains, resulted in a decrease in BMD to levels slightly above (lumbar spine) or near (total hip) baseline. The BMD loss after stopping a 12-month course of romosozumab presented here is consistent with that previously reported after 2 years of romosozumab treatment [20]. In contrast, a single dose of IV zoledronate 5 mg generally maintained the BMD gains achieved after a second course of romosozumab 210 mg QM during months 36 to 48 at the lumbar spine and proximal femur.

The efficacy of a single dose of zoledronate over an interval of 24 months is consistent with previous studies demonstrating a long duration of the effect of zoledronate in preserving bone density [27,28,29]. Results from our study are also consistent with results from previous studies demonstrating the effectiveness of bisphosphonate therapy to prevent bone loss upon stopping estrogen, denosumab, or PTH receptor agonists [11, 12, 27, 30,31,32].

The findings from our study should be considered in the context of several limitations including the small sample sizes of the two treatment groups, short study follow-up periods, and use of surrogate outcomes (percentage changes in BMD and bone turnover markers) for efficacy evaluation. Additionally, we evaluated the effect of only the single 5 mg dose of zoledronate administered approximately 4 weeks after the last dose of romosozumab. However, the major strength of this phase 2 study, overall, is that it has provided safety and efficacy data for up to 2 consecutive years of treatment with romosozumab in postmenopausal women with low bone mass, information on the effects of stopping romosozumab therapy, and information on a second course of romosozumab treatment as well as clinically relevant patterns of using the antiresorptive agents denosumab and zoledronate following romosozumab therapy.

Osteoporosis is a chronic disease requiring life-long management. Since all currently available osteoporosis therapies are reversible over variable time frames, there is a need to understand the proper sequence of treatments as romosozumab is incorporated into osteoporosis management. Recent studies demonstrate that therapy with anabolic or bone-forming agents that increase bone formation by stimulation of osteoblasts such as romosozumab, teriparatide, and abaloparatide in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis is more effective in reducing fracture risk than therapy with oral bisphosphonates [12, 21, 22, 33]. This has led expert opinion to suggest that the treatment sequence of a bone-forming agent, followed by a potent antiresorptive agent, be used more often to treat patients at high risk for fracture [34, 35]. Our current study provides additional evidence that transitioning patients from a treatment with romosozumab to a potent antiresorptive, in this case zoledronate, can maintain the robust BMD gains accrued with romosozumab treatment, similar to what has previously been demonstrated for denosumab and alendronate [21, 22]. There are no clear guidelines for choosing among these antiresorptive agents to follow romosozumab. That decision will depend upon the clinical characteristics of the patients and concerns about side effects and adherence to the various follow-on therapies.

In conclusion, the treatment sequence of romosozumab for 12 months followed by zoledronate preserves BMD for up to 2 years, is well tolerated, and is an option for patients with osteoporosis at high risk for fracture.

References

Ferrari S, Adachi JD, Lippuner K, Zapalowski C, Miller PD, Reginster JY, Torring O, Kendler DL, Daizadeh NS, Wang A, O'Malley CD, Wagman RB, Libanati C, Lewiecki EM (2015) Further reductions in nonvertebral fracture rate with long-term denosumab treatment in the FREEDOM open-label extension and influence of hip bone mineral density after 3 years. Osteoporos Int 26:2763–2771

Cosman F, Crittenden DB, Ferrari S, Khan A, Lane NE, Lippuner K, Matsumoto T, Milmont CE, Libanati C, Grauer A (2018) FRAME study: the foundation effect of building bone with 1 year of romosozumab leads to continued lower fracture risk after transition to denosumab. J Bone Miner Res 33:1219–1226

Austin M, Yang YC, Vittinghoff E, Adami S, Boonen S, Bauer DC, Bianchi G, Bolognese MA, Christiansen C, Eastell R, Grauer A, Hawkins F, Kendler DL, Oliveri B, McClung MR, Reid IR, Siris ES, Zanchetta J, Zerbini CA, Libanati C, Cummings SR, Trial F (2012) Relationship between bone mineral density changes with denosumab treatment and risk reduction for vertebral and nonvertebral fractures. J Bone Miner Res 27:687–693

Bouxsein ML, Eastell R, Lui LY, Wu LA, de Papp AE, Grauer A, Marin F, Cauley JA, Bauer DC, Black DM, Project FBQ (2019) Change in bone density and reduction in fracture risk: a meta-regression of published trials. J Bone Miner Res 34:632–642

Recker RR, Delmas PD, Halse J, Reid IR, Boonen S, Garcia-Hernandez PA, Supronik J, Lewiecki EM, Ochoa L, Miller P, Hu H, Mesenbrink P, Hartl F, Gasser J, Eriksen EF (2008) Effects of intravenous zoledronic acid once yearly on bone remodeling and bone structure. J Bone Miner Res 23:6–16

Zebaze RM, Libanati C, Austin M, Ghasem-Zadeh A, Hanley DA, Zanchetta JR, Thomas T, Boutroy S, Bogado CE, Bilezikian JP, Seeman E (2014) Differing effects of denosumab and alendronate on cortical and trabecular bone. Bone 59:173–179

Jiang Y, Zhao JJ, Mitlak BH, Wang O, Genant HK, Eriksen EF (2003) Recombinant human parathyroid hormone (1-34) [teriparatide] improves both cortical and cancellous bone structure. J Bone Miner Res 18:1932–1941

Forteo (teriparatide injection) Prescribing Information (2012) Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, US. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/021318s036lbl.pdf. Accessed 19 February 2020

Tymlos™ (abaloparatide) Prescribing Information (2017) Radius health, Inc., Waltham, MA, US. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/208743lbl.pdf. Accessed 19 February 2020

Leder BZ, Tsai JN, Uihlein AV, Wallace PM, Lee H, Neer RM, Burnett-Bowie SA (2015) Denosumab and teriparatide transitions in postmenopausal osteoporosis (the DATA-switch study): extension of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 386:1147–1155

Niimi R, Kono T, Nishihara A, Hasegawa M, Kono T, Sudo A (2018) Efficacy of switching from teriparatide to bisphosphonate or denosumab: a prospective, randomized, open-label trial. JBMR Plus 2:289–294

Bone HG, Cosman F, Miller PD, Williams GC, Hattersley G, Hu MY, Fitzpatrick LA, Mitlak B, Papapoulos S, Rizzoli R, Dore RK, Bilezikian JP, Saag KG (2018) ACTIVExtend: 24 months of alendronate after 18 months of abaloparatide or placebo for postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 103:2949–2957

Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, Lewiecki EM, Tanner B, Randall S, Lindsay R, Foundation NO (2014) Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 25:2359–2381

Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, Clarke BL, Harris ST, Hurley DL, Kleerekoper M, Lewiecki EM, Miller PD, Narula HS, Pessah-Pollack R, Tangpricha V, Wimalawansa SJ, Watts NB (2016) American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Postmenopausal Osteoporosis - 2016. Endocr Pract 22:1–42

Padhi D, Jang G, Stouch B, Fang L, Posvar E (2011) Single-dose, placebo-controlled, randomized study of AMG 785, a sclerostin monoclonal antibody. J Bone Miner Res 26:19–26

Padhi D, Allison M, Kivitz AJ, Gutierrez MJ, Stouch B, Wang C, Jang G (2014) Multiple doses of sclerostin antibody romosozumab in healthy men and postmenopausal women with low bone mass: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Pharmacol 54:168–178

McClung MR, Grauer A, Boonen S, Bolognese MA, Brown JP, Diez-Perez A, Langdahl BL, Reginster JY, Zanchetta JR, Wasserman SM, Katz L, Maddox J, Yang YC, Libanati C, Bone HG (2014) Romosozumab in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density. N Engl J Med 370:412–420

Chavassieux P, Portero-Muzy N, Roux JP, Horlait S, Dempster DW, Wang A, Wagman RB, Chapurlat R (2019) Reduction of cortical bone turnover and erosion depth after 2 and 3 years of denosumab: iliac bone histomorphometry in the FREEDOM trial. J Bone Miner Res 34:626–631

Ominsky MS, Brown DL, Van G, Cordover D, Pacheco E, Frazier E, Cherepow L, Higgins-Garn M, Aguirre JI, Wronski TJ, Stolina M, Zhou L, Pyrah I, Boyce RW (2015) Differential temporal effects of sclerostin antibody and parathyroid hormone on cancellous and cortical bone and quantitative differences in effects on the osteoblast lineage in young intact rats. Bone 81:380–391

McClung MR, Brown JP, Diez-Perez A, Resch H, Caminis J, Meisner P, Bolognese MA, Goemaere S, Bone HG, Zanchetta JR, Maddox J, Bray S, Grauer A (2018) Effects of 24 months of treatment with romosozumab followed by 12 months of denosumab or placebo in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density: a randomized, double-blind, phase 2, parallel group study. J Bone Miner Res 33:1397–1406

Cosman F, Crittenden DB, Adachi JD, Binkley N, Czerwinski E, Ferrari S, Hofbauer LC, Lau E, Lewiecki EM, Miyauchi A, Zerbini CA, Milmont CE, Chen L, Maddox J, Meisner PD, Libanati C, Grauer A (2016) Romosozumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 375:1532–1543

Saag KG, Petersen J, Brandi ML, Karaplis AC, Lorentzon M, Thomas T, Maddox J, Fan M, Meisner PD, Grauer A (2017) Romosozumab or alendronate for fracture prevention in women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 377:1417–1427

Langdahl BL, Libanati C, Crittenden DB, Bolognese MA, Brown JP, Daizadeh NS, Dokoupilova E, Engelke K, Finkelstein JS, Genant HK, Goemaere S, Hyldstrup L, Jodar-Gimeno E, Keaveny TM, Kendler D, Lakatos P, Maddox J, Malouf J, Massari FE, Molina JF, Ulla MR, Grauer A (2017) Romosozumab (sclerostin monoclonal antibody) versus teriparatide in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis transitioning from oral bisphosphonate therapy: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 390:1585–1594

EVENITY® (romosozumab-aqqg) US Prescribing Information (2019) Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA, US. https://www.pi.amgen.com/~/media/amgen/repositorysites/pi-amgen-com/evenity/evenity_pi_hcp_english.ashx. Accessed 24 February 2020

EVENITY® (romosozumab) EU Summary of Product Characteristics (2019) Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA, US. https://www.ucb.com/_up/ucb_com_presscenter/documents/98f3864197f1030c.pdf. Accessed 24 February 2020

Kendler DL, Bone HG, Massari FE, Gielen E, Palacios S, Maddox J, Yan C, Yue S, Dinavahi RV, Libanati C, Grauer A (2019) Bone mineral density gains with a second 12-month course of romosozumab therapy following placebo or denosumab. Osteoporos Int 30:2437–2448

Anastasilakis AD, Papapoulos SE, Polyzos SA, Appelman-Dijkstra NM, Makras P (2019) Zoledronate for the prevention of bone loss in women discontinuing denosumab treatment: a prospective 2-year clinical trial. J Bone Miner Res 34:2220–2228

Grey A, Bolland MJ, Horne A, Mihov B, Gamble G, Reid IR (2017) Duration of antiresorptive activity of zoledronate in postmenopausal women with osteopenia: a randomized, controlled multidose trial. CMAJ 189:e1130–e1136

McClung M, Miller P, Recknor C, Mesenbrink P, Bucci-Rechtweg C, Benhamou CL (2009) Zoledronic acid for the prevention of bone loss in postmenopausal women with low bone mass: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 114:999–1007

Ascott-Evans BH, Guanabens N, Kivinen S, Stuckey BG, Magaril CH, Vandormael K, Stych B, Melton ME (2003) Alendronate prevents loss of bone density associated with discontinuation of hormone replacement therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 163:789–794

Freemantle N, Satram-Hoang S, Tang ET, Kaur P, Macarios D, Siddhanti S, Borenstein J, Kendler DL, DAPS Investigators (2012) Final results of the DAPS (Denosumab Adherence Preference Satisfaction) study: a 24-month, randomized, crossover comparison with alendronate in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 23:317–326

Reid IR, Horne AM, Mihov B, Gamble GD (2017) Bone loss after denosumab: only partial protection with zoledronate. Calcif Tissue Int 101:371–374

Kendler DL, Marin F, Zerbini CAF, Russo LA, Greenspan SL, Zikan V, Bagur A, Malouf-Sierra J, Lakatos P, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, Lespessailles E, Minisola S, Body JJ, Geusens P, Moricke R, Lopez-Romero P (2018) Effects of teriparatide and risedronate on new fractures in post-menopausal women with severe osteoporosis (VERO): a multicentre, double-blind, double-dummy, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 391:230–240

Cosman F, Nieves JW, Dempster DW (2017) Treatment sequence matters: anabolic and antiresorptive therapy for osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 32:198–202

McClung MR (2017) Using osteoporosis therapies in combination. Curr Osteoporos Rep 15:343–352

Acknowledgements

Representatives of the sponsor, Amgen Inc., designed the study in collaboration with some of the study investigators and UCB Pharma, and performed analyses according to a prespecified statistical analysis plan. Amgen Inc. maintained the study database. The first author (MRM) and 2 authors from Amgen Inc. (AG and YS) take responsibility of the integrity of the data analysis. The first author (MRM) wrote the first draft of the manuscript; all authors contributed to subsequent drafts of the manuscript, participated in the analysis and/or interpretation of the data, and participated in the critical review and revision of the report. All authors approved the final version for submission. Lisa A. Humphries, PhD, of Amgen Inc. and Martha Mutomba (on behalf of Amgen Inc.) provided medical writing support.

Funding

This study was funded by Amgen Inc., UCB Pharma, and Astellas.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

MRM has received consulting fees and honoraria from Amgen and consulting fees from Myovant. MAB has received contract fees from and has been a speaker for Amgen. JPB has received research funding from Amgen, Eli Lilly, Mereo Biopharma, Radius Health, and Servier; has received consulting fees from Amgen, Eli Lilly, Orimed, and Servier; and has received lecture fees from Amgen and Eli Lilly. J-YR has received research funding from IBSA-Genevrier, Mylan, CNIEL, and Radius Health; has received lecture fees from IBSA-Genevrier, Mylan, CNIEL, and Dairy Research Council; and has received consulting fees from or participated in paid advisory boards for IBSA-Genevrier, Mylan, Radius Health, and Pierre Fabre. BLL has received research funding from Amgen and Novo Nordisk; has received consulting fees from Amgen, Eli Lilly, and UCB; and has received lecture fees from Amgen, Eli Lilly, and UCB. JM, YS, and MR are employees of and hold stock in Amgen. PDM is an employee of and holds stock in UCB Pharma. AG was an employee of Amgen at the time of the study and holds stock in Amgen.

Data sharing

Qualified researchers may request data from Amgen clinical studies. Complete details are available at https://wwwext.amgen.com/science/clinical-trials/clinical-data-transparency-practices/.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 238 kb).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McClung, M., Bolognese, M., Brown, J. et al. A single dose of zoledronate preserves bone mineral density for up to 2 years after a second course of romosozumab. Osteoporos Int 31, 2231–2241 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-020-05502-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-020-05502-0