Abstract

Summary

Accurate patient risk perception of adverse health events promotes greater autonomy over, and motivation towards, health-related lifestyles.

Introduction

We compared self-perceived fracture risk and 3-year incident fracture rates in postmenopausal women with a range of morbidities in the Global Longitudinal study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW).

Methods

GLOW is an international cohort study involving 723 physician practices across ten countries (Europe, North America, Australasia); 60,393 women aged ≥55 years completed baseline questionnaires detailing medical history and self-perceived fracture risk. Annual follow-up determined self-reported incident fractures.

Results

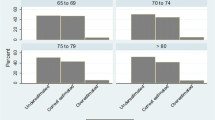

In total 2,945/43,832 (6.8 %) sustained an incident fracture over 3 years. All morbidities were associated with increased fracture rates, particularly Parkinson's disease (hazard ratio [HR]; 95 % confidence interval [CI], 3.89; 2.78–5.44), multiple sclerosis (2.70; 1.90–3.83), cerebrovascular events (2.02; 1.67–2.46), and rheumatoid arthritis (2.15; 1.53–3.04) (all p < 0.001). Most individuals perceived their fracture risk as similar to (46 %) or lower than (36 %) women of the same age. While increased self-perceived fracture risk was strongly associated with incident fracture rates, only 29 % experiencing a fracture perceived their risk as increased. Under-appreciation of fracture risk occurred for all morbidities, including neurological disease, where women with low self-perceived fracture risk had a fracture HR 2.39 (CI 1.74–3.29) compared with women without morbidities.

Conclusions

Postmenopausal women with morbidities tend to under-appreciate their risk, including in the context of neurological diseases, where fracture rates were highest in this cohort. This has important implications for health education, particularly among women with Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, or cerebrovascular disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Horton R et al (2011) Priority actions for the non-communicable disease crisis. Lancet 377:1438–1447

World Health Organization The global burden of disease: 2004 update. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/2004_report_update/en/index.html. Accessed 15 February 2013.

van Staa TP, Dennison EM, Leufkens HG, Cooper C (2001) Epidemiology of fractures in England and Wales. Bone 29:517–522

Cummings SR, Melton LJ (2002) Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet 359:1761–1767

Chen JS, Hogan C, Lyubomirsky G, Sambrook PN (2011) Women with cardiovascular disease have increased risk of osteoporotic fracture. Calcif Tissue Int 88:9–15

Drake MT, Murad MH, Mauck KF et al (2012) Clinical review. Risk factors for low bone mass-related fractures in men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:1861–1870

Janghorbani M, Van Dam RM, Willett WC, Hu FB (2007) Systematic review of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus and risk of fracture. Am J Epidemiol 166:495–505

Vestergaard P (2007) Discrepancies in bone mineral density and fracture risk in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes–a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 18:427–444

Loke YK, Cavallazzi R, Singh S (2011) Risk of fractures with inhaled corticosteroids in COPD: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. Thorax 66:699–708

David C, Confavreux CB, Mehsen N, Paccou J, Leboime A, Legrand E (2010) Severity of osteoporosis: what is the impact of co-morbidities? Joint Bone Spine 77(Suppl 2):S103–S106

Bazelier MT, van Staa TP, Uitdehaag BM, Cooper C, Leufkens HG, Vestergaard P, Herings RM, de Vries F (2012) Risk of fractures in patients with multiple sclerosis: a population-based cohort study. Neurology 78:1967–1973

Dennison EM, Compston JE, Flahive J et al (2012) Effect of co-morbidities on fracture risk: findings from the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW). Bone 50:1288–1293

Cline RR, Farley JF, Hansen RA, Schommer JC (2005) Osteoporosis beliefs and antiresorptive medication use. Maturitas 50:196–208

Gerend MA, Aiken LS, West SG, Erchull MJ (2004) Beyond medical risk: investigating the psychological factors underlying women's perceptions of susceptibility to breast cancer, heart disease, and osteoporosis. Health Psychol 23:247–258

Cooper V, Moyle GJ, Fisher M, Reilly G, Ewan J, Liu HC, Horne R (2011) Beliefs about antiretroviral therapy, treatment adherence and quality of life in a 48-week randomised study of continuation of zidovudine/lamivudine or switch to tenofovir DF/emtricitabine, each with efavirenz. AIDS Care 23:705–713

Horne R, Clatworthy J, Hankins M (2010) High adherence and concordance within a clinical trial of antihypertensives. Chronic Illn 6:243–251

Kucukarslan SN (2012) A review of published studies of patients' illness perceptions and medication adherence: lessons learned and future directions. Res Social Adm Pharm 8:371–382

Siris ES, Gehlbach S, Adachi JD et al (2011) Failure to perceive increased risk of fracture in women 55 years and older: the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW). Osteoporos Int 22:27–35

Hooven FH, Adachi JD, Adami S et al (2009) The Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW): rationale and study design. Osteoporos Int 20:1107–1116

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE (2000) How to Score Version 2 of the SF-36 Health Survey. Quality Metric, Incorporated, Lincoln, RI

Gerend MA, Erchull MJ, Aiken LS, Maner JK (2006) Reasons and risk: factors underlying women's perceptions of susceptibility to osteoporosis. Maturitas 55:227–237

Phillipov G, Phillips PJ, Leach G, Taylor AW (1998) Public perceptions and self-reported prevalence of osteoporosis in South Australia. Osteoporos Int 8:552–556

Giangregorio L, Papaioannou A, Thabane L, DeBeer J, Cranney A, Dolovich L, Adili A, Adachi JD (2008) Do patients perceive a link between a fragility fracture and osteoporosis? BMC Musculoskelet Disord 9:38

Taylor BC, Schreiner PJ, Stone KL, Fink HA, Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Bowman PJ, Ensrud KE (2004) Long-term prediction of incident hip fracture risk in elderly white women: study of osteoporotic fractures. J Am Geriatr Soc 52:1479–1486

Gibson JC, Summers GD (2011) Bone health in multiple sclerosis. Osteoporos Int 22:2935–2949

Invernizzi M, Carda S, Viscontini GS, Cisari C (2009) Osteoporosis in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 15:339–346

US Department of Health and Human Services (2004) Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General (2004) Office of the Surgeon General, Rockville, USA, p http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/bonehealth/content.html

Goodin DS, Frohman EM, Garmany GP Jr, Halper J, Likosky WH, Lublin FD, Silberberg DH, Stuart WH, van den Noort S (2002) Disease modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the MS Council for Clinical Practice Guidelines. Neurology 58:169–178

Thurman DJ, Stevens JA, Rao JK (2008) Practice parameter: assessing patients in a neurology practice for risk of falls (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 70:473–479

Zesiewicz TA, Sullivan KL, Arnulf I, Chaudhuri KR, Morgan JC, Gronseth GS, Miyasaki J, Iverson DJ, Weiner WJ (2010) Practice Parameter: treatment of nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson disease: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 74:924–931

Grimes D, Gordon J, Snelgrove B et al (2012) Canadian guidelines on Parkinson's disease. Can J Neurol Sci 39:S1–S30

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence NICE Pathways: Stroke overview. http://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/stroke. Accessed 15 February 2013.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Parkinson's Disease: National clinical guideline for diagnosis and management in primary and secondary care. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/10984/30087/30087.pdf. Accessed 15 February 2013.

MS Australia Practice for health professionals: balance for people with multiple sclerosis (MS). http://www.msaustralia.org.au/documents/MS-Practice/balance.pdf. Accessed 15 February 2013.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Multiple sclerosis: National clinical guideline for diagnosis and management in primary and secondary care. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/10930/46699/46699.pdf. Accessed 15 February 2013.

(2002) Guidelines for the management of rheumatoid arthritis: 2002 Update. Arthritis Rheum 46:328–346

(2003) American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: guidelines on osteoporosis in gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterology 124: 791–794

American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Task Force Standards for the Diagnosis and Management of Patients with COPD. http://www.thoracic.org/clinical/copd-guidelines/resources/copddoc.pdf. Accessed 15 February 2013.

British Columbia Ministry of Health Rheumatoid Arthritis: diagnosis, management and monitoring. http://www.bcguidelines.ca/pdf/rheumatoid_arthritis.pdf. Accessed 15 February 2013.

Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A et al (2011) Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 60:571–607

National Clinical Guideline Centre Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13029/49425/49425.pdf. Accessed 15 February 2013.

National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions Rheumatoid arthritis: National Clinical Guideline for Management and Treatment In Adults. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK51812/pdf/TOC.pdf. Accessed 15 February 2013.

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners Clinical guideline for the diagnosis and management of early rheumatoid arthritis. http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/file/publications/synopses/cp118-early-rheum-arthritis.pdf. Accessed 15 February 2013.

Kasje WN, Denig P, De Graeff PA, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM (2004) Physicians' views on joint treatment guidelines for primary and secondary care. Int J Qual Health Care 16:229–236

Kvamme OJ, Olesen F, Samuelson M (2001) Improving the interface between primary and secondary care: a statement from the European Working Party on Quality in Family Practice (EQuiP). Qual Health Care 10:33–39

Giangregorio L, Dolovich L, Cranney A, Adili A, Debeer J, Papaioannou A, Thabane L, Adachi JD (2009) Osteoporosis risk perceptions among patients who have sustained a fragility fracture. Patient Educ Couns 74:213–220

de Groot V, Beckerman H, Lankhorst GJ, Bouter LM (2003) How to measure comorbidity. A critical review of available methods. J Clin Epidemiol 56:221–229

Stockwell T, Donath S, Cooper-Stanbury M, Chikritzhs T, Catalano P, Mateo C (2004) Under-reporting of alcohol consumption in household surveys: a comparison of quantity-frequency, graduated-frequency and recent recall. Addiction 99:1024–1033

Hundrup YA, Høidrup S, Obel EB, Rasmussen NK (2004) The validity of self-reported fractures among Danish female nurses: comparison with fractures registered in the Danish National Hospital Register. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 32:136–143

Chen Z, Kooperberg C, Pettinger MB, Bassford T, Cauley JA, LaCroix AZ, Lewis CE, Kipersztok S, Borne C, Jackson RD (2004) Validity of self-report for fractures among a multiethnic cohort of postmenopausal women: results from the Women's Health Initiative observational study and clinical trials. Menopause 11:264–274

Rosati G (2001) The prevalence of multiple sclerosis in the world: an update. Neurol Sci 22:117–139

Carmona L, Villaverde V, Hernandez-Garcia C, Ballina J, Gabriel R, Laffon A (2002) The prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in the general population of Spain. Rheumatology (Oxford) 41:88–95

Cimmino MA, Parisi M, Moggiana G, Mela GS, Accardo S (1998) Prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in Italy: the Chiavari Study. Ann Rheum Dis 57:315–318

de Lau LM, Breteler MM (2006) Epidemiology of Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol 5:525–535

Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, O'Fallon WM (1999) The epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis in Rochester, Minnesota, 1955–1985. Arthritis Rheum 42:415–420

Guo F, He D, Zhang W, Walton RG (2012) Trends in prevalence, awareness, management, and control of hypertension among United States adults, 1999 to 2010. J Am Coll Cardiol 60:599–606

Acknowledgments

We thank the physicians, project coordinators, and women participating in GLOW.

Funding

Funding/Support and Role of the Sponsor: Financial support for the GLOW study is provided by Warner Chilcott Company, LLC and sanofi-aventis to the Center for Outcomes Research, University of Massachusetts Medical School. The sponsors had no involvement in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The design, conduct, and interpretation of the GLOW data are undertaken by an independent steering committee. The Medical Research Council and the University of Southampton provided funding infrastructure support for manuscript completion.

Conflicts of interest

CLG has no disclosures. EMD has no disclosures. JEC has undertaken paid consultancy work for Servier, Shire, Nycomed, Novartis, Amgen, Procter & Gamble, Wyeth, Pfizer, The Alliance for Better Bone Health, Roche, and GlaxoSmithKline; has been a paid speaker for and received reimbursement, travel and accommodation from Servier, Procter & Gamble, and Lilly; and has received research grants from Servier R&D and Procter & Gamble. SA has received speaker honoraria from Eli Lilly and Amgen; and consultancy honoraria from MSD, Eli Lilly, Amgen and Novartis. JDA has been a consultant/speaker for Amgen, Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Nycomed, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, Roche, sanofi-aventis, Servier, Warner Chilcott and Wyeth; and has conducted clinical trials for Amgen, Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, Roche, sanofi-aventis, Warner Chilcott, Wyeth, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. FAA has received funding from The Alliance for Better Bone Health (sanofi-aventis and Warner Chilcott). SB has received research grants from Amgen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, sanofi-aventis, Roche, and GlaxoSmithKline; and has received honoraria from, served on Speakers' Bureaus for, and acted as a consultant/Advisory Board member for Amgen, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Procter & Gamble, sanofi-aventis, and Servier. RC has received funding from the French Ministry of Health, Merck, Servier, Lilly, and Procter & Gamble; has received honoraria from Amgen, Servier, Novartis, Lilly, Roche, and sanofi-aventis; and has acted as a consultant/Advisory Board member for Amgen, Merck, Servier, Nycomed, and Novartis. AD-P has received consulting fees and lectured for Eli Lilly, Amgen, Procter & Gamble, Servier, and Daiichi-Sankyo; has been an expert witness for Merck; and is a consultant/Advisory Board member for Novartis, Eli Lilly, Amgen, and Procter & Gamble; has received honoraria from Novartis, Lilly, Amgen, Procter & Gamble, and Roche; has been an expert witness for Merck; and has acted as a consultant/Advisory Board member for Novartis, Lilly, Amgen, and Procter & Gamble. SLG has acted as a consultant/Advisory Board member for Amgen, Lilly, and Merck; and has received research grants from The Alliance for Better Bone Health (sanofi-aventis and Proctor & Gamble) and Lilly. FHH has received funding from The Alliance for Better Bone Health (sanofi-aventis and Warner Chilcott). AZL has received funding from The Alliance for Better Bone Health (sanofi-aventis and Warner Chilcott) and is an Advisory Board member for Amgen. JWN has no disclosures. JCN has undertaken paid consultancy work for Roche Diagnostics, Daiichi-Sankyo, Proctor & Gamble, and Nycomed; has been a paid speaker for and received reimbursement, travel and accommodation from Roche Diagnostics, Novartis, Daiichi-Sankyo, and Procter & Gamble; and has received research grants from The Alliance for Better Bone Health and Amgen. JP has received research grants from Amgen, Kyphon, Novartis, and Roche; has received other research support (equipment) from GE Lunar; has served on Speakers' Bureaus for Amgen, sanofi-aventis, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, Lilly Deutschland, Orion Pharma, Merck, Merckle, Nycomed, and Procter & Gamble; and has acted as an Advisory Board member for Novartis, Roche, Procter & Gamble, and Teva. MR is on the Speakers' Bureau for Roche. CR has received honoraria from and acted as a consultant/Advisory Board member for Alliance, Amgen, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Nycomed, Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Servier, and Wyeth. KGS received consulting fees or other remuneration from Eli Lilly & Co, Merck, Novartis, and Amgen; and has conducted paid research for Eli Lilly & Co, Merck, Novartis, and Amgen. SS has received research grants from Wyeth, Lilly, Novartis, and Alliance; has served on Speakers' Bureaus for Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and Procter & Gamble; has received honoraria from Procter & Gamble; and has acted as a consultant/Advisory Board member for Lilly, Argen, Wyeth, Merck, Roche, and Novartis. ESS has acted as a consultant for Amgen, Lilly, Novartis, and The Alliance for Better Bone Health; and has served on Speakers' Bureaus in the past year for Amgen, and Lilly. NBW has received honoraria for lectures in the past year from Amgen, Novartis, and Warner Chilcott; has acted as a consultant in the past year for Amgen, Arena, Baxter, InteKrin, Johnson & Johnson, Lilly, Medpace, Merck, NPS, Orexigen, Pfizer/Wyeth, Takeda, Vivus, Warner Chilcott; has received research support (through University) from Amgen, Merck, and NPS; and co-founded, has stock options and is a director of OsteoDynamics. AW has no disclosures. CC has received consulting fees from and lectured for Amgen, The Alliance for Better Bone Health (sanofi-aventis and Warner Chilcott), Lilly, Merck, Servier, Novartis, and Roche-GSK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Table S1

Age-adjusted Kaplan–Meier 3-year hazard ratios for fracture by morbidities and self-perceived fracture risk (DOC 43 kb)

Table S2

Unadjusted Kaplan–Meier 3-year incident fracture rate estimates according to the cumulative morbidity index and grouped morbidities, stratified by self-perceived fracture risk (DOC 41 kb)

Table S3

Age-adjusted Kaplan–Meier 3-year hazard ratios according to morbidity, by self-perceived fracture risk (DOC 36 kb)

Table S4

Age-adjusted Kaplan–Meier 3-year hazard ratios according to morbidity index and grouped morbidities, by self-perceived fracture risk (DOC 35 kb)

Table S5

Potential influences on self-perceived fracture risk in postmenopausal women (DOC 49 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gregson, C.L., Dennison, E.M., Compston, J.E. et al. Disease-specific perception of fracture risk and incident fracture rates: GLOW cohort study. Osteoporos Int 25, 85–95 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-013-2438-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-013-2438-y