Abstract

Summary

This study assessed whether osteoporosis diagnosis and treatment after an osteoporotic fracture can be increased by providing osteoporosis reading material to patients and family doctors or by watching a videocassette about osteoporosis. Educating patients about osteoporosis had little impact on whether a woman received an osteoporosis diagnosis or treatment.

Introduction

The purpose of this study was to investigate the impact of two education-based interventions on osteoporosis diagnosis and treatment in women ≥50 years of age after fragility fracture.

Methods

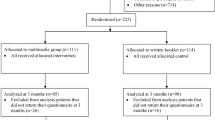

Six to eight months after fracture, women were randomized into three groups: (1) control, (2) written materials, or (3) videocassette and written materials. Written materials for both the patient and physician detailed osteoporosis, fragility fracture, and available treatments; written materials for physicians were provided through patients. The educational videocassette presented similar information as the written material, but in greater depth. Rates of osteoporosis diagnosis and treatment following intervention were compared among groups using survival analysis methods. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.0167.

Results

At randomization, 1,174 women were without osteoporosis diagnosis and treatment, and after follow-up, 12% of the control group, 15% of the written materials group (p = 0.073), and 16% (p = 0.036) of the videocassette and written materials group were diagnosed with osteoporosis (statistical comparisons to control). Treatment rates were 8% for the control group, 12% for the written materials group (p = 0.052), and 11% for the videocassette and written materials group (p = 0.157). At randomization, 1,314 women were without treatment and after follow-up therapy was initiated in 10% of the control group, 13% of the written materials group (p = 0.107), and 13% of the videocassette and written materials group (p = 0.238).

Conclusions

The educational interventions assessed in this trial were not satisfactory to increase osteoporosis diagnosis or treatment in recently fractured women to a clinically meaningful degree.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papaioannou A, Kennedy CC, Ioannidis G, Sawka A, Hopman WM, Pickard L, Brown JP, Josse RG, Kaiser S, Anastassiades T, Goltzman D, Papadimitropoulos M, Tenenhouse A, Prior JC, Olszynski WP, Adachi JD (2008) The impact of incident fractures on health-related quality of life: 5 years of data from the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study. Osteoporos Int 20:703–714

Ioannidis G, Papaioannou A, Hopman WM, Khtar-Danesh N, Anastassiades T, Pickard L, Kennedy CC, Prior JC, Olszynski WP, Davison KS, Goltzman D, Thabane L, Gafni A, Papadimitropoulos EA, Brown JP, Josse RG, Hanley DA, Adachi JD (2009) Relation between fractures and mortality: results from the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study. CMAJ 181:265–271

Wiktorowicz ME, Goeree R, Papaioannou A, Adachi JD, Papadimitropoulos E (2001) Economic implications of hip fracture: health service use, institutional care and cost in Canada. Osteoporos Int 12:271–278

Kanis JA, Johnell O, De Laet C, Johansson H, Oden A, Delmas P, Eisman J, Fujiwara S, Garnero P, Kroger H, McCloskey EV, Mellstrom D, Melton LJ, Pols H, Reeve J, Silman A, Tenenhouse A (2004) A meta-analysis of previous fracture and subsequent fracture risk. Bone 35:375–382

Siris ES, Chen YT, Abbott TA, Barrett-Connor E, Miller PD, Wehren LE, Berger ML (2004) Bone mineral density thresholds for pharmacological intervention to prevent fractures. Arch Intern Med 164:1108–1112

Cranney A, Tsang JF, Leslie WD (2009) Factors predicting osteoporosis treatment initiation in a regionally based cohort. Osteoporos Int 20:1621–1625

Bessette L, Ste-Marie LG, Jean S, Davison KS, Beaulieu M, Baranci M, Bessant J, Brown JP (2008) The care gap in diagnosis and treatment of women with a fragility fracture. Osteoporos Int 19:79–86

Papaioannou A, Kennedy CC, Ioannidis G, Gao Y, Sawka AM, Goltzman D, Tenenhouse A, Pickard L, Olszynski WP, Davison KS, Kaiser S, Josse RG, Kreiger N, Hanley DA, Prior JC, Brown JP, Anastassiades T, Adachi JD (2008) The osteoporosis care gap in men with fragility fractures: the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study. Osteoporos Int 19:581–587

Metge CJ, Leslie WD, Manness LJ, Yogendran M, Yuen CK, Kvern B (2008) Postfracture care for older women: gaps between optimal care and actual care. Can Fam Physician 54:1270–1276

Bessette L, Ste-Marie LG, Jean S, Davison KS, Beaulieu M, Baranci M, Bessant J, Brown JP (2008) Recognizing osteoporosis and its consequences in Quebec (ROCQ): background, rationale, and methods of an anti-fracture patient health-management programme. Contemp Clin Trials 29:194–210

Kreiger N, Tenenhouse A, Joseph L, Mackenzie T, Poliquin S, Brown J, Prior J, Rittmaster R (1999) The Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos): background, rationale, methods. Can J Aging 18:376–387

Cadarette SM, Jaglal SB, Raman-Wilms L, Beaton DE, Paterson JM (2010) Osteoporosis quality indicators using healthcare utilization data. Osteoporos Int. doi:10.1007/s00198-010-1329-8

Brown JP, Josse RG (2002) 2002 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada. CMAJ 167:S1–34

(2003) Osteoporosis update. Osteoporosis Canada. http://www.osteoporosis.ca/local/files/health_professionals/pdfs/osteoupdate_special_e.pdf. Accessed 25 April 2010

Gardner MJ, Brophy RH, Demetrakopoulos D, Koob J, Hong R, Rana A, Lin JT, Lane JM (2005) Interventions to improve osteoporosis treatment following hip fracture. A prospective, randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 87:3–7

Majumdar SR, Johnson JA, McAlister FA, Bellerose D, Russell AS, Hanley DA, Morrish DW, Maksymowych WP, Rowe BH (2008) Multifaceted intervention to improve diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis in patients with recent wrist fracture: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ 178:569–575

Majumdar SR, Johnson JA, Bellerose D, McAlister FA, Russell AS, Hanley DA, Garg S, Lier DA, Maksymowych WP, Morrish DW, Rowe BH (2011) Nurse case-manager vs multifaceted intervention to improve quality of osteoporosis care after wrist fracture: randomized controlled pilot study. Osteoporos Int 22:223–230

Cranney A, Lam M, Ruhland L, Brison R, Godwin M, Harrison MM, Harrison MB, Anastassiades T, Grimshaw JM, Graham ID (2008) A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women with wrist fractures: a cluster randomized trial. Osteoporos Int 19:1733–1740

Jaglal SB, Hawker G, Bansod V, Salbach NM, Zwarenstein M, Carroll J, Brooks D, Cameron C, Bogoch E, Jaakkimainen L, Kreder H (2009) A demonstration project of a multi-component educational intervention to improve integrated post-fracture osteoporosis care in five rural communities in Ontario, Canada. Osteoporos Int 20:265–274

Hawker G, Ridout R, Ricupero M, Jaglal S, Bogoch E (2003) The impact of a simple fracture clinic intervention in improving the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis in fragility fracture patients. Osteoporos Int 14:171–178

Laliberte MC, Perreault S, Dragomir A, Goudreau J, Rodrigues I, Blais L, Damestoy N, Corbeil D, Lalonde L (2010) Impact of a primary care physician workshop on osteoporosis medical practices. Osteoporos Int 21:1471–1485

Dell R, Greene D, Schelkun SR, Williams K (2008) Osteoporosis disease management: the role of the orthopaedic surgeon. J Bone Joint Surg Am 4(90):188–94, 188–194

Bogoch ER, Elliot-Gibson V, Beaton DE, Jamal SA, Josse RG, Murray TM (2006) Effective initiation of osteoporosis diagnosis and treatment for patients with a fragility fracture in an orthopaedic environment. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88:25–34

Majumdar SR, Beaupre LA, Harley CH, Hanley DA, Lier DA, Juby AG, Maksymowych WP, Cinats JG, Bell NR, Morrish DW (2007) Use of a case manager to improve osteoporosis treatment after hip fracture: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 167:2110–2115

Sander B, Elliot-Gibson V, Beaton DE, Bogoch ER, Maetzel A (2008) A coordinator program in post-fracture osteoporosis management improves outcomes and saves costs. J Bone Joint Surg Am 90:1197–1205

Charalambous CP, Kumar S, Tryfonides M, Rajkumar P, Hirst P (2002) Management of osteoporosis in an orthopaedic department: audit improves practice. Int J Clin Pract 56:620–621

Murray AW, McQuillan C, Kennon B, Gallacher SJ (2005) Osteoporosis risk assessment and treatment intervention after hip or shoulder fracture. A comparison of two centres in the United Kingdom. Injury 36:1080–1084

McLellan AR, Gallacher SJ, Fraser M, McQuillian C (2003) The fracture liaison service: success of a program for the evaluation and management of patients with osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int 14:1028–1034

Miki RA, Oetgen ME, Kirk J, Insogna KL, Lindskog DM (2008) Orthopaedic management improves the rate of early osteoporosis treatment after hip fracture. A randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 90:2346–2353

Rozental TD, Makhni EC, Day CS, Bouxsein ML (2008) Improving evaluation and treatment for osteoporosis following distal radial fractures. A prospective randomized intervention. J Bone Joint Surg Am 90:953–961

Majumdar SR, Lier DA, Beaupre LA, Hanley DA, Maksymowych WP, Juby AG, Bell NR, Morrish DW (2009) Osteoporosis case manager for patients with hip fractures: results of a cost-effectiveness analysis conducted alongside a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med 169:25–31

Majumdar SR, Lier DA, Rowe BH, Russell AS, McAlister FA, Maksymowych WP, Hanley DA, Morrish DW, Johnson JA (2011) Cost-effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention to improve quality of osteoporosis care after wrist fracture. Osteoporos Int. doi:10.1007/s00198-010-1412-1

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the ROCQ program staff, particularly program coordinators Nathalie Migneault and Lucie Vaillancourt and administrative assistant Julie Parrot. We also acknowledge the contributions of the regional coordinators and research assistants: Sylvie Bélanger, Geneviève Corneau, Isabel Lajeunesse, Pierre-Antoine Landry, Lise Lemire, Anne-Marie Louis XVI, Julie Simard, and Lyse Roy; the Office Clerks: Huguette Bédard, Kateri Bisson, Isabelle Bourque, Alexandre Brown, Marie-Hélène Brown, Francine Lavoie, Vanessa Poulin, Catherine Richard; and the interviewers: Lina Bélisle, Francine Bilodeau, Ginette David, Janot Dumont, Susie Gagnon, Ghislaine Fortin, Louise Groleau, Denise Hubert-Milot, Michèle Paris, Edith Picard-Marcoux, Lucie Riou. Finally, we thank the Regional Directors of this program: Dr. Pierre Dagenais (University of Montreal, Montreal), Dr. Kim Latendresse (University of Montreal, Montreal), Dr. Pierre Major (University of Montreal, Montreal), Dr. Frédéric Morin (Centre Hospitalier Régional deTrois-Rivières, Trois-Rivières), Dr. Suzanne Morin (McGill University, Montreal), and Dr. Josée Villeneuve (Laval University, Quebec City) for their support during the implementation of the program and their critical scientific advice. We also thank past members of the ROCQ executive, Louise Lafortune, Christine Chin, Luc Sauriol, and Andy McClenaghan, for their insightful guidance. Lastly, we appreciate all CaMos investigators for allowing us to utilize pertinent sections of the CaMos questionnaires for ROCQ.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Bessette has received research grants from Abbott, Amgen, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Eli Lilly, Merck, Pfizer, and Roche, has received consulting fees or other remuneration from Abbott, Amgen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche and has participated on the speakers bureau for Amgen, Novartis, Merck, Pfizer, Roche, and Warner Chilcott.

Dr. Brown has received research grants from Abbott, Amgen, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and Roche, has received consulting fees or other remuneration from Abbott, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Merck, and Warner Chilcott and has participated on the speakers bureau for Eli Lilly, Amgen, Novartis, Merck, and Warner Chilcott.

Dr. Davison has received consulting fees or other remuneration from Amgen and Servier and has participated on the Speakers’ Bureau for Amgen, Merck Frosst Warner Chilcott and Servier.

Dr. Ste-Marie has received research grants from the Alliance for Better Bone Health and Novartis, has received consulting fees or other remuneration from the Alliance for Better Bone Health, Amgen, Novartis, Eli Lilly, and Servier and has participated on the Speakers’ Bureau for the Alliance for Better Bone Health, Amgen, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Servier, and Merck. No other authors have a conflict or interest to disclose

The ROCQ program was funded by Merck Frosst Canada, Inc., Warner Chilcott, sanofi-aventis group, Amgen Canada Inc., Eli Lilly Canada, Inc., and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Canada, Inc. None of the funding sources had a role in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data or in the decision to publish this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bessette, L., Davison, K.S., Jean, S. et al. The impact of two educational interventions on osteoporosis diagnosis and treatment after fragility fracture: a population-based randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos Int 22, 2963–2972 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1533-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1533-1