Abstract

Summary

Our objective was to assess the association of self-reported non-persistence (stopping fracture-prevention medication for more than 1 month) and self-reported non-compliance (missing doses of prescribed medication) with perceived need for fracture-prevention medication, concerns regarding long-term harm from and/or dependence upon medications, and medication-use self-efficacy (confidence in one’s ability to successfully take medication in the context of their daily life).

Introduction

Non-persistence (stopping medication prematurely) and non-compliance (not taking medications at the prescribed times) with oral medications to prevent osteoporotic fractures is widespread and attenuates their fracture reduction benefit.

Methods

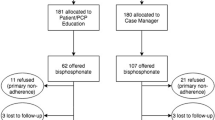

Cross-sectional survey and medical record review of 729 patients at a large multispecialty clinic in the United States prescribed an oral bisphosphonate between January 1, 2006 and March 31, 2007.

Results

Low perceived necessity for fracture-prevention medication was strongly associated with non-persistence independent of other predictors, but not with non-compliance. Concerns about medications were associated with non-persistence, but not with non-compliance. Low medication-use self-efficacy was associated with non-persistence and non-compliance.

Conclusions

Non-persistence and non-compliance with oral bisphosphonate medication have different, albeit overlapping, sets of predictors. Low perceived necessity of fracture-prevention medication, high concerns about long-term safety of and dependence upon medication , and low medication-use self-efficacy all predict non-persistence with oral bisphosphonates, whereas low medication-use self-efficacy strongly predicts non-compliance with oral bisphosphonate medication. Assessment of and influence of these medication attitudes among patients at high risk of fracture are likely necessary to achieve better persistence and compliance with fracture-prevention therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Nguyen ND, Ahlborg HG, Center JR, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV (2007) Residual lifetime risk of fractures in women and men. J Bone Miner Res 22:781–788

Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Nevitt MC, Bauer DC, Genant HK, Haskell WL, Marcus R, Ott SM, Torner JC, Quandt SA, Reiss TF, Ensrud KE (1996) Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. Lancet 348:1535–1541

Harris ST, Watts NB, Genant HK, McKeever CD, Hangartner T, Keller M, Chesnut CH 3rd, Brown J, Eriksen EF, Hoseyni MS, Axelrod DW, Miller PD (1999) Effects of risedronate treatment on vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. Vertebral Efficacy with Risedronate Therapy (VERT) Study Group. JAMA 282:1344–1352

McClung MR, Geusens P, Miller PD, Zippel H, Bensen WG, Roux C, Adami S, Fogelman I, Diamond T, Eastell R, Meunier PJ, Reginster JY (2001) Effect of risedronate on the risk of hip fracture in elderly women. Hip Intervention Program Study Group. N Engl J Med 344:333–340

Reginster J, Minne HW, Sorensen OH, Hooper M, Roux C, Brandi ML, Lund B, Ethgen D, Pack S, Roumagnac I, Eastell R (2000) Randomized trial of the effects of risedronate on vertebral fractures in women with established postmenopausal osteoporosis. Vertebral Efficacy with Risedronate Therapy (VERT) Study Group. Osteoporos Int 11:83–91

Wells G, Cranney A, Peterson J, Boucher M, Shea B, Robinson V, Coyle D, Tugwell P (2008) Risedronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD004523

MacLean C, Newberry S, Maglione M, McMahon M, Ranganath V, Suttorp M, Mojica W, Timmer M, Alexander A, McNamara M, Desai SB, Zhou A, Chen S, Carter J, Tringale C, Valentine D, Johnsen B, Grossman J (2008) Systematic review: comparative effectiveness of treatments to prevent fractures in men and women with low bone density or osteoporosis. Ann Intern Med 148:197–213

Cramer JA, Gold DT, Silverman SL, Lewiecki EM (2007) A systematic review of persistence and compliance with bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 18:1023–1031

Kothawala P, Badamgarav E, Ryu S, Miller RM, Halbert RJ (2007) Systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world adherence to drug therapy for osteoporosis. Mayo Clin Proc 82:1493–1501

Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, Fairchild CJ, Fuldeore MJ, Ollendorf DA, Wong PK (2008) Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health 11:44–47

Huybrechts KF, Ishak KJ, Caro JJ (2006) Assessment of compliance with osteoporosis treatment and its consequences in a managed care population. Bone 38:922–928

Caro JJ, Ishak KJ, Huybrechts KF, Raggio G, Naujoks C (2004) The impact of compliance with osteoporosis therapy on fracture rates in actual practice. Osteoporos Int 15:1003–1008

Siris ES, Harris ST, Rosen CJ, Barr CE, Arvesen JN, Abbott TA, Silverman S (2006) Adherence to bisphosphonate therapy and fracture rates in osteoporotic women: relationship to vertebral and nonvertebral fractures from 2 US claims databases. Mayo Clin Proc 81:1013–1022

Rabenda V, Mertens R, Fabri V, Vanoverloop J, Sumkay F, Vannecke C, Deswaef A, Verpooten GA, Reginster JY (2008) Adherence to bisphosphonates therapy and hip fracture risk in osteoporotic women. Osteoporos Int 19:811–818

Cotte FE, Mercier F, De Pouvourville G (2008) Relationship between compliance and persistence with osteoporosis medications and fracture risk in primary health care in France: a retrospective case-control analysis. Clin Ther 30:2410–2422

Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M (1999) The beliefs about medications questionnaire: the development of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation about medication. Psychol Health 14:1–24

Horne R (1999) Patients' beliefs about treatment: the hidden determinant of treatment outcome? J Psychosom Res 47:491–495

Horne R, Weinman J (2002) Self-regulation and self-management in asthma: exploring the role of illness perception and treatment beliefs in explaining non-adherence to preventer medication. Psychol Health 17:17–32

Horne R, Cooper V, Gellaitry G, Date HL, Fisher M (2007) Patients' perceptions of highly active antiretroviral therapy in relation to treatment uptake and adherence: the utility of the necessity-concerns framework. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 45:334–341

Tarn DM, Heritage J, Paterniti DA, Hays RD, Kravitz RL, Wenger NS (2006) Physician communication when prescribing new medications. Arch Intern Med 166:1855–1862

Becker MH, Rosenstock IM (1987) Comparing social learning theory and the health belief model. In: Ward WB (ed) Advances in health behavior and promotion. JAI, Greenwich, pp 245–249

O'Leary A (1985) Self-efficacy and health. Behav Res Ther 23:437–451

Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH (1988) Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Q 15:175–183

Brus H, van de Laar M, Taal E, Rasker J, Wiegman O (1999) Determinants of compliance with medication in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the importance of self-efficacy expectations. Patient Educ Couns 36:57–64

Johnson MO, Neilands TB, Dilworth SE, Morin SF, Remien RH, Chesney MA (2007) The role of self-efficacy in HIV treatment adherence: validation of the HIV treatment adherence self-efficacy scale (HIV-ASES). J Behav Med 30:359–370

Schoenthaler A, Ogedegbe G, Allegrante JP (2009) Self-efficacy mediates the relationship between depressive symptoms and medication adherence among hypertensive African Americans. Health Educ Behav 36:127–137

Resnick B, Wehren L, Orwig D (2003) Reliability and validity of the self-efficacy and outcome expectations for osteoporosis medication adherence scales. Orthop Nurs 22:139–147

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S (2000) Applied logistic regression. Wiley, New York

Pregibon D (1980) Goodness of link tests for generalized linear models. Appl Stat 29:15–24

Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 51:1173–1182

Herr NR (2006) Mediation with dichotomous variables. URL: http://nrherr.bol.ucla.edu/Mediation/logmed.html. Accessed on July 15, 2009

MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V (2002) A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods 7:83–104

MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH (1993) Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Eval Rev 17:144–158

Schwarzer R, Fuchs R (1995) Self-efficacy and health behaviors. In: Connor M, Norman P (eds) Predicting health behavior. Open University Press, Philadelphia, pp 163–196

Clifford S, Barber N, Horne R (2008) Understanding different beliefs held by adherers, unintentional nonadherers, and intentional nonadherers: application of the necessity-concerns framework. J Psychosom Res 64:41–46

Cline RR, Farley JF, Hansen RA, Schommer JC (2005) Osteoporosis beliefs and antiresorptive medication use. Maturitas 50:196–208

McHorney CA, Schousboe JT, Cline RR, Weiss TW (2007) The impact of osteoporosis medication beliefs and side-effect experiences on non-adherence to oral bisphosphonates. Curr Med Res Opin 23:3137–3152

Blumberg EJ, Hovell MF, Kelley NJ, Vera AY, Sipan CL, Berg JP (2005) Self-report INH adherence measures were reliable and valid in Latino adolescents with latent tuberculosis infection. J Clin Epidemiol 58:645–648

Choo PW, Rand CS, Inui TS, Lee ML, Cain E, Cordeiro-Breault M, Canning C, Platt R (1999) Validation of patient reports, automated pharmacy records, and pill counts with electronic monitoring of adherence to antihypertensive therapy. Med Care 37:846–857

Farmer KC (1999) Methods for measuring and monitoring medication regimen adherence in clinical trials and clinical practice. Clin Ther 21:1074–1090 discussion 1073

Garber MC, Nau DP, Erickson SR, Aikens JE, Lawrence JB (2004) The concordance of self-report with other measures of medication adherence: a summary of the literature. Med Care 42:649–652

Haynes RB, Taylor DW, Sackett DL, Gibson ES, Bernholz CD, Mukherjee J (1980) Can simple clinical measurements detect patient noncompliance? Hypertension 2:757–764

Mason BJ, Matsuyama JR, Jue SG (1995) Assessment of sulfonylurea adherence and metabolic control. Diabetes Educ 21:52–57

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Park Nicollet Institute and a small unrestricted grant from Proctor and Gamble, Inc.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Schousboe: current research support from Eli Lilly, Inc (2008–2009). Prior consultant work for Roche, Inc., 2008

Dr. Dowd: none

Dr. Davison: none

Dr. Kane: consultant for SCAN Health Plan, United Health Group, and Medtronics

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: psychometric (measurement) properties of survey scales

Appendix: psychometric (measurement) properties of survey scales

All survey items were pre-tested in detail with volunteers with osteoporosis (who were not participants in the main study) to assess whether or not they were clear and interpreted in the way we intended. We randomly split the study sample into two halves, and examined the psychometric properties of the multi-item scales separately in each half. Principal components analysis was done to establish the factor structure of all items within the multi-item scales in both groups. Internal consistency reliability of the multi-item scales was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, and item-scale correlations were evaluated. The unidimensionality of the summated rating (Likert) scales were established using principal components of each scale separately, and a ratio of the first to second eigenvalue greater than 3.0 was considered to be strong evidence of unidimensionality.

Perceived need for fracture-prevention medication was assessed by a seven-item scale, adapted for those with osteoporosis and at high risk of fracture, analogous to the disease-specific necessity scales of Horne and colleagues [16]. The raw summed scores were squared to achieve a normal distribution. The internal consistency reliability in each half of the study sample, respectively, was 0.87 and 0.86. There was also strong evidence of this being a unidimensional scale, in that principal components analysis showed the ratio of the first to second eigenvalue to be 4.77 and 4.09, respectively, in each half of the study sample. The item-scale correlation ranges were 0.69 to 0.80 and 0.74 to 0.82, respectively, in each half of the study sample.

Concerns about medications was measured by an 11-item scale that assessed patient perceptions regarding the perceived long-term safety of and dependence upon medications, and whether or not medications in their view are over-prescribed. Importantly, this scale does not assess actually experienced side effects (adverse reactions) to any medications. The internal consistency reliability of this scale was 0.85 in both halves of the study sample. The ratio of the first to second eigenvalue was 3.92 and 3.55, respectively, in each half of the study sample. The item-scale correlation ranges were 0.58 to 0.68 and 0.56 to 0.73, respectively, in each half of the study sample.

Medication-use self-efficacy was measured with a seven-item scale derived from that of Resnick and colleagues [27]. In our pre-test, participants expressed difficulty rating their self-efficacy with the original linear rating scale of Resnick and colleagues, and hence we converted this to a Likert scale with five response categories. We also eliminated items in Resnick’s original that referred to side effects or medication costs. We conceived of self-efficacy as confidence in the ability to execute medication-use behavior in the context of one’s daily life and that side effects or concerns about costs may lead one to choose not to take medication but would not influence the confidence to take it should they so choose. Our scale nonetheless had an internal consistency reliability in the two study sample halves, respectively, of 0.94 and 0.93, and was strongly unidimensional (ratio of first to second eigenvalues of 10.58 and 10.38, respectively, in the two study halves). The item-scale correlation ranges were 0.82 to 0.90 and 0.81 to 0.90, respectively, in the two study halves.

Principal components analysis with orthogonal rotation of all three scales together within both study halves showed the loadings of all items onto their hypothesized factor to be 0.51 or higher, and the loadings onto the other two factors to be 0.20 or lower.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schousboe, J.T., Dowd, B.E., Davison, M.L. et al. Association of medication attitudes with non-persistence and non-compliance with medication to prevent fractures. Osteoporos Int 21, 1899–1909 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-009-1141-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-009-1141-5