Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

Urinary incontinence (UI) is a common and embarrassing complaint for pregnant women. Reported prevalence and incidence figures show a large range, due to varying case definitions, recruited population and study methodology. Precise prevalence and incidence figures on (bothersome) UI are of relevance for health care providers, policy makers and researchers. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the prevalence and incidence of UI in pregnancy in the general population for relevant subgroups and assessed experienced bother.

Methods

All observational studies published between January 1998 and October 2018 reporting on prevalence and/or incidence of UI during pregnancy were included. All women, regardless of weeks of gestation and type of UI presented in all settings, were of interest. A random-effects model was used. Subgroup analyses were conducted by parity, trimester and subtype of UI.

Results

The mean (weighted) prevalence based on 44 included studies, containing a total of 88.305 women, was 41.0% (range of 9–75%). Stress urinary incontinence (63%) is the most prevalent type of UI; 26% of the women reported daily loss, whereas 40% reported loss on a monthly basis. Bother was experienced as mild to moderate.

Conclusions

UI is very prevalent and rising with the weeks of gestation in pregnancy. SUI is the most common type and in most cases it was a small amount. Bother for UI is heterogeneously assessed and experienced as mild to moderate by pregnant women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI) is the complaint of involuntary loss of urine [1]. It is a common and embarrassing problem, evoking substantial individual morbidity, loss in quality of life and socio-economic costs [2, 3]. In addition to the loss of bladder control, the need to wear incontinence pads often harms the individuality and self-confidence of young pre-partum women [4]. UI ranges from occasionally leaking urine when coughing or sneezing [stress UI (SUI)] to UI preceded by urgency [urgency UI (UUI)], or a combination of both [mixed UI (MUI)]. In the peri-partum period women often experience UI for the first time. In general, SUI is more related to the peri-partum period, whereas the prevalence of UUI and MUI increases with age [5]. Pregnancy and (vaginal) delivery are important risk factors in the development of UI in life [2, 6]. Moreover, when SUI presents during pregnancy, the risk of having SUI at 12 years post-partum is significant [7].

The prevalence and incidence of UI in pregnancy is widely researched. However, these prevalence and/or incidence figures vary greatly throughout published reports, depending on the local setting, case definitions applied, recruited population (trimester of pregnancy and parity), and study methodology [8, 9]. Former systematic reviews focused on the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders (PFDs) among community-dwelling women [10], the prevalence of UI in nulliparous women [11] or in female athletes [12]. To our knowledge, no systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence and incidence of UI in pregnancy is available. Reliable prevalence and incidence rates on UI in pregnancy are not only needed to indicate the burden of the health problem, but also to better inform health professionals, policy makers and researchers to set priorities and to assist in planning management of UI[13]. Furthermore, it is known that not all pregnant women are bothered by experiencing UI. It is reported that the crude UI prevalence rate is higher and probably overestimated compared to the prevalence rate of significant or bothersome UI [3]. As bothersome UI is associated with help-seeking behaviour, this discrepancy may have crucial consequences for research planning, health care providers and policy makers [14]. However, a clear and widely accepted definition of bothersome UI still does not exist, which results in the use of heterogeneous terminology and measurement instruments.

Therefore, the primary aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to examine the pooled overall prevalence and incidence of UI in pregnancy in the general population, specified for relevant subcategories (trimester of pregnancy, parity, type of UI, frequency and amount). A secondary aim was to provide an overview of the measurement instruments and their outcomes for bother in relation to UI as used in included studies.

Methods

The MOOSE statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses was followed [15]. The research protocol was published in the PROSPERO database (registration number CRD42018111991).

Search strategy

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies reporting on the prevalence and/or incidence of UI during pregnancy and experienced bother in relation to UI. We searched the electronic databases of PubMed, EMBASE and CINAHL.

We used the following search terms to search all databases: pregnancy, pregn*, prepartum, pre-partum, pre partum, peripartum, peri-partum, peri partum, nulliparous, primiparous, primigrav*, primipar*, multiparous, multigrav*, multipar*, urinary incontinence, urine loss, pelvic floor disorders, pelvic floor dysfunctions, leaking urine, incontinence, prevalence, incidence, epidemiology, bothersomeness, bother* and quality of life. In the Appendix the complete search strategy for PubMed is provided. This search string was adapted for use in the other databases.

Eligibility criteria

Observational studies published between January 1, 1998, and January 1, 2019, in Dutch, English, Portuguese, German and French were included. All studies examining prevalence and/or incidence of UI among adult primi- and multigravid women, regardless of weeks of gestation, type of UI, setting and country, were of interest. Outcomes of interest were prevalence and/or incidence of (bothersome) UI. Exclusion criteria were: articles not available in full or not reporting an overall UI prevalence of any frequency and studies examining only twin pregnancies. When articles did not report a prevalence or incidence figure or response rate, an attempt was made for estimation from the information provided. Throughout this article we use the term bother (in relation to UI) as umbrella term for related constructs [impact on daily life or quality of life (QOL)].

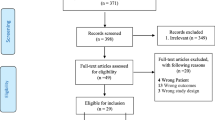

Study selection

Titles and/or abstracts of studies retrieved using the search strategy and those from additional sources were screened independently by two reviewers (HM and EB) to identify studies that potentially meet the inclusion criteria. The full text of these potentially eligible studies were retrieved and independently assessed for eligibility by two reviewers. Any disagreement on eligibility was resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (BB). All the included articles were reference checked.

Data extraction and risk of bias

Information on each study was extracted in a standardized data extraction form, based on the Cochrane Public Health Data Extraction and Assessment template[16].

To assess the risk of bias, the Joanna Briggs critical appraisal tool for studies reporting prevalence data was used [17, 18]. The checklist consists of nine questions, with the response options yes, no, unclear or not applicable. Overall risk of study bias was rated as low (defined as 8–9 criteria answered as ‘yes’), moderate (4–7 criteria answered as ‘yes’) or high risk (≤3 criteria answered as ‘yes’). The response option not applicable (occasionally scored in criteria 5) was considered to be a ‘yes’. Two reviewers extracted data independently. Inconsistencies were identified and resolved through discussion including a third author if necessary.

Characteristics regarding measurement instruments for bother were extracted in a separate standardized extraction form. The form contains items such as measurement instrument, related construct and measurement results.

Summary measures, statistical analyses and heterogeneity

We used a random effects model to pool the inverse variance (IV) weighted prevalence of UI in individuals to avoid undue influence on the summary estimate from smaller and less precise studies or studies with a very small prevalence. Pooled prevalence and incidence values were reported with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The degree of heterogeneity was determined by the I2 statistic, with I2 > 75% labelled as considerable heterogeneity [19].

We performed subgroup analyses based on trimester, parity, type and frequency of UI, as these factors may explain why studies show varying prevalence figures. Trimesters 1, 2 and 3 were defined as weeks 1–13, 14–26 and 27 to at term (42 weeks), respectively. STATA Statistical Software, release 15, was used for analysis.

To determine the overall experienced bother in relation to UI across included studies, the total scores of the different measurement instruments for bother were converted to a (standardized) 0 to 100 scale, with 0 indicating no bother and 100 indicating extremely bothered. We classified 1 to 20 as no to mild bother, 20 to 40 as mild to moderate bother, 40 to 60 as moderate to severe, 60 to 80 as severe to very severe and 80 to 100 as extremely severe bother.

Results

Study selection

Among the 1338 papers initially identified, 44 met the eligibility criteria (Fig. 1), resulting in a total of 88,305 participants. All included studies were observational and published between 1998 and January 1, 2019.

Risk of bias

The risk of bias items for each study are shown in Table 1. High, moderate and low risks of bias were considered to be present in 3, 34 and 7 studies respectively. Risk of bias items with the lowest ratings were 8 and 9, and risk of bias items with the highest ratings were 1 and 4.

Study characteristics

Seventeen studies originated from Asia, 15 from Europe, 8 from the USA, 3 from Africa and 1 from Oceania. The majority of women were included from a (tertiary) hospital. Other studies included women from a civil registration system [20], midwifery area [21], hospital and maternity unit [22] or obstetric/child health clinic [23, 24]. Table 1 summarizes the study characteristics of included studies.

Thirteen studies reported on (measurement instruments for) bother, whereas one study (73) reported on two measurement instruments. The result of only one measurement instrument was reported for this study, as the second one (SF-36) was incomplete. Table 2 provides an overview of the measurement instruments as used in included studies, with the original and the converted (0–100 scale) measurement results.

Six different measurement instruments for bother were used, of which the ICIQ-UI SF was most frequently used. Two studies reported the results of the ICIQ-UI SF as categories [25, 26]. One measurement instrument was self-constructed and non-validated [27].

Synthesis of results

Overall prevalence

Forty-four studies involving a total of 88.305 women were used to calculate the overall prevalence of UI. The weighted average of UI prevalence among pregnant women was 41.0% (CI 95% 34.0–48.0%; I2: 99.77%), regardless of trimester, parity or type of UI (Fig. 2). The lowest prevalence of UI found in the included studies was 9% [28] and the highest prevalence 75% [29]. Prevalence figures for low, moderate and high risk of bias studies were 38% (95% 18.0–58.0), 41% (95% 36.0–46.0) and 47% (95% 39.0–54.0) respectively.

Subcategories trimester of pregnancy, type of UI and parity

Five out of the 44 studies included women from trimester 1 or 2 or two out of three pregnancy trimesters. Fifteen studies recruited women from the third trimester, with an overall UI prevalence of 47% (95% CI: 37.0–58.0%). Twenty-four studies recruited women from trimester 1–3, with an overall UI prevalence of 40% (95% CI: 34.0–45.0%). Based on 24 studies, SUI accounts for 63% of UI cases, whereas UUI, MUI and unexplained UI were 12%, 22% and 3% respectively.

When parity is taken into account, 42% of nulliparous women experience UI (based on 12 studies; 95% CI 33.0–51.0%; I2 = 98.6%), whereas four studies reporting only on primiparous women found an overall UI prevalence of 31% (95% CI 26.0–36.0%; I2 90.6%). Twenty-seven studies included women with any parity, resulting in a pooled prevalence of 42% (95% CI 32.0–53.0%; I2 99.8%).

Based on 12 out of 44 studies, the overall prevalence for UI in trimesters 1, 2 and 3 is 9% (95% CI 6.0–12.0%; I2 97.7%), 19% (95% CI 12.0–25.0%; I2 98.7%) and 34% (95% CI 23.0–46.0%; I2 99.0%) respectively.

Subcategories frequency and amount of UI

Based on ten studies, monthly UI accounts for 40% of UI cases (95% CI 23.0–57.0%; I2 99.0%), weekly UI for 33% (95% CI 23.0–43.0%; I2 94.8%) and daily UI for 26% (95% CI 20.0–32.0%; I2 86.9%).

The majority of studies (n = 9), reporting on the amount of urine loss (n = 14), used the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ-UI SF) to assess this parameter (none, small, moderate, large amount) [30]. Three studies reported separately the ICIQ-UI SF amount item, showing that the majority (79.2–86.9%) of UI cases lose a small amount. Other descriptions of amount of urine lost were: drops or just a little, more like a trickle, more than a trickle [31, 32], a few droplets, a stream [33] and drops, small splashes and more [26, 34].

Bother

Thirteen studies reported on impact on daily life, quality of life or bother. It was heterogeneously assessed; however, the ICIQ-UI SF was used in the majority of studies (n = 7). In two studies question 3 of the ICIQ-UI SF on interference in daily life was reported as a measurement instrument for bother. Other measurement instruments that were used only once were the Incontinence Quality of Life (I-QOL), Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ-7), Wagner’s quality of life questionnaire and a self-constructed non-validated questionnaire. The overall bother of UI during pregnancy, on a 0 to 100 scale, ranges between 9.5 and 34.1, consistent with mild to moderate bother, whereas the experienced bother is higher in the 3rd trimester (between 13.3 and 57.6) (Table 3).

Case definition

The majority of studies (n = 30) did not specify a case definition for UI. Four studies used as a case definition ‘any leakage’ or used the frequency (n = 5), amount/volume (n = 1), timeframe (n = 2) or UI type (n = 3) criteria in their case definition, or a combination of those (n = 3).

Incidence

Few studies have examined incidence of UI during pregnancy, using different trimesters of pregnancy and case definitions. Therefore, no pooling was done for this outcome. Five studies reported on new-onset UI during pregnancy among women who were continent 12 months before the index pregnancy [31, 32] or who had no UI previous to pregnancy [20, 22, 26]. Daly et al. reported that 21.7% of nulliparous women experienced any new-onset urinary leakage in early pregnancy [32]. The frequency of leakage among new-onset UI was less than once per month in 55% of cases and on a monthly, weekly and daily basis in 26.7%, 13.3% and 5.0% of cases respectively. The majority (83.1%) experienced drops or just a little amount of leakage. Brown et al. [31] reported 146 incident cases for any UI in early pregnancy (≤ 24 weeks of gestation; 16.4%) compared to 561 cases in late pregnancy (31 weeks; 63.2%). It appeared that new cases of SUI accounted for more than two thirds of prevalent cases in early and late pregnancy, 70.4% and 73.9%, respectively. Hvidman et al. concluded that UI incidence during pregnancy was 16.8% among nulliparous and 8.4% among primiparous women [20]. Overall, incidence rates in early pregnancy among nulliparous women range between 16.4% and 21.7% [31, 32]. When considering late pregnancy, the incidence rate increases to 45.6–63.2% [22, 31]. The incidence rate of UI during first pregnancy, regardless of trimester, is 16.8–39.1% [20, 26].

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to examine the pooled prevalence and incidence of UI during pregnancy and to provide an overview of measurement instruments, including the measurement results, to assess bother in relation to UI. The results show an overall mean prevalence of UI during pregnancy of 41%, with a range of 9–75%. The prevalence numbers rise with gestational period from 9% in the first trimester to 34% in the third. SUI is the most prevalent type of UI, accounting for 63% of cases. Twenty-six percent of the women reported daily loss, whereas 40% reported loss on a monthly basis. Most of the cases reported a small amount of urine loss.

Incidence/new onset UI in nulliparous women in early pregnancy varied between 16.4% and 21.7%[31, 32]. This variation might be explained by the different case definition used for UI (e.g. any UI [32] in contrast to UI at least once a month [31]). Incidence in late pregnancy increased to 63.2% [31]. Over 70% of new onset UI was SUI. The high prevalence and rising incidence numbers of SUI during pregnancy might be due to several factors such as physiological weight gain, which results in increased intra-abdominal pressure on the bladder and pelvic floor muscles [35]. Additionally, it is known that pregnant women with SUI have significantly less pelvic floor muscle strength and thickness [36] and/or a larger hiatal area at rest and during pelvic floor muscle contraction [37]. But also previous childbirth and high body mass index are risk factors for developing SUI [38, 39].

Most included studies showed a moderate risk of bias. Although several factors influence reported prevalence rates, e.g. case definition, studies with moderate or high risk of bias may distort prevalence and/or incidence rates. The prevalence rate among three studies with high risk of bias is 47% compared to 38% among studies with low risk of bias (in studies with a moderate risk of bias the prevalence is 41%). As studies with a low risk of bias tend to have a slightly lower prevalence, it is likely that the real prevalence of UI in pregnant women is in the range of 38–41%.

Only 13 out of 44 studies reported bother in relation to UI; these studies used a variety of measurement instruments. In an attempt to provide an overall assessment of experienced bother in relation to UI, we (arbitrarily) chose to standardize the measurement results of different bother scales to a 0 to 100 scale. Bother of UI during pregnancy ranges between 9.5 and 34.1 on a (standardized) 0 to 100 scale. The 0 to 100 scale can be regarded as a visual analogue scale (VAS). The VAS is a valid and reproducible method to measure the impact of UI on QOL [40]. No studies are known that report on cut-off points for QOL in pregnant women with UI. Therefore, cut-off points must be interpreted cautiously. One study comparing the VAS with a measure that assesses the impact on functioning in patients with pain identified three classes: class 1, mild interference (score 1–34); class 2, moderate interference (score 35–64); class 3, severe interference with daily life (score 65–100) [41]. Based on these classes the overall bother of UI during pregnancy is mild and in the third trimester mild to moderate. One study reporting on bother of UI in the last 4 weeks of pregnancy reported the highest bother of 57 [42]. This might be due to the rising prevalence over time in pregnancy [29, 34, 42,43,44,45,46].

The ICI provides an overview of (recommended) grade A (high-quality) measurement instruments for bother in relation to UI [3] and advises to report prevalence figures in combination with the experienced bother. The ICIQ-UI SF, IIQ and I-QOL, for example, are rated as grade A measurement instruments. Wagner’s QOL and the VAS are not incorporated in the ICI overview, nor is the separate use of question 3 of the ICIQ-UI SF as a bother measure. A closer look at the measurement instruments shows that there are differences with regard to assessed constructs and domains. The ICIQ-UI SF is a quick way to assess frequency, severity and bother of UI. The IIQ, I-QOL and Wagner’s QOL scale assess bother of UI with a variety of subscales such as psychosocial impact, social embarrassment, relations, and physical activity and provide therefore more in-depth information.

This systematic review revealed that the reporting of prevalence with a measure of bother is not common practice yet. To improve the reporting of UI prevalence, it is recommended that in research projects both prevalence and bother should be measured with high quality measurement instruments in line with the recommendations of ICI. In clinical practice, measurement results of bother support healthcare professionals in the clinical reasoning process as it may provide information on diagnosis or prognosis or may evaluate one’s own actions. At the same time, it standardizes communication with colleagues. Moreover, measurement results can be used to better inform patients about their situation and to involve them more easily in joint therapy decisions (shared decision making).

The construct bother in relation to UI seems difficult to grasp, as included studies used different definitions. The following terms were used: effect on daily activities/everyday life, interference on daily life, health-related quality of life, severity, lifestyle changes, (perceived) impact on quality of life, distress, experienced discomfort and amount of bother. As the degree of bother is related to help-seeking behaviour for UI [47, 48], it is of importance to define the construct bother (what does bother in relation to UI mean for pregnant women) and quantify bother. When bother is well defined and quantified, this will support researchers in selecting the appropriate measurement instrument and interpretation of the results.

Based on the prevalence figures, it would appear that UI in pregnancy is an enormous healthcare problem. However, not everyone seeks (medical) help for UI immediately. Several factors determine help-seeking behaviour of pregnant women, such as awareness of treatment possibilities and the experienced burden of UI [48, 49]. Also the belief that UI will resolve by itself after delivery and the lack of knowledge that UI during pregnancy raises the odds for post-partum UI substantially obstructs help-seeking [50, 51].

Management of UI should be directed to women who seek help for UI, but may also be directed towards women who experience bother or have risk factors for developing UI (prevention). Such uncertainties require further evaluation and data on duration of treatment effects of PFM(G)T [52]. Maternity care workers need to assess women for the presence, severity and bother of UI and, in consultation with them, develop a specially tailored plan of care to meet the women’s needs.

The strength of this systematic review is the large number of included studies, which resulted in the availability of prevalence and incidence numbers for different subpopulations (countries, parity, trimester of pregnancy) and for different purposes (research planning, health care providers and policy makers). To our knowledge, this review is the first one that focused on assessment methods for bother in relation to UI and degree of adherence to the recommendations of ICI with regard to this topic.

The limitations of this systematic review are, first, the presence of substantial clinical heterogeneity of the studies. Clinical heterogeneity is due to differences in: case definition (any UI or different frequencies of UI in a certain period of time), population (primigravida-multigravida) or periods researched (first, second, third trimester or any specific trimester). Second, the considerable statistical heterogeneity of the studies resulted in large CIs. Third, as the Joanna Briggs critical appraisal tool does not recommend cut-off points for high, moderate or low risk of bias, we arbitrarily chose the cut-off points reported in this systematic review to explore possible differences in prevalence numbers if stratified for risk of bias. However, we did not include or exclude studies based on risk of bias.

Conclusion

UI is a very common symptom in pregnancy, and the prevalence rises as weeks of gestation progress. SUI is the most common types and in most of the cases a small amount of urine was lost. The level of bother for UI is heterogeneously assessed and is experienced as mild to moderate by pregnant women.

References

Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, Swift SE, Berghmans B, Lee J, Monga A, Petri E, Rizk DE, Sand PK, Schaer GN (2010) An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J 21 (1):5–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-009-0976-9

Morkved S, Bo K, Schei B, Salvesen KA. Pelvic floor muscle training during pregnancy to prevent urinary incontinence: a single-blind randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(2):313–9.

Abrams A, Cardozo L, Wagg A, Wein A, editors. Incontinence 6th edition. Bristol, UK: ICI-ICS. International Continence Society; 2017.

Stafne SN, Salvesen K, Romundstad PR, Torjusen IH, Mørkved S. Does regular exercise including pelvic floor muscle training prevent urinary and anal incontinence during pregnancy? A randomised controlled trial. Bjog. 2012;119(10):1270–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03426.x.

Botlero R, Davis SR, Urquhart DM, Shortreed S, Bell RJ. Age-specific prevalence of, and factors associated with, different types of urinary incontinence in community-dwelling Australian women assessed with a validated questionnaire. Maturitas. 2009;62(2):134–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.12.017.

Boyle R, Hay-Smith EJ, Cody JD, Morkved S. Pelvic floor muscle training for prevention and treatment of urinary and faecal incontinence in antenatal and postnatal women. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 10:Cd007471. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007471.pub2.

Viktrup L, Rortveit G, Lose G. Risk of stress urinary incontinence twelve years after the first pregnancy and delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(2):248–54. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000226860.01127.0e.

Lin YH, Chang SD, Hsieh WC, Chang YL, Chueh HY, Chao AS, et al. Persistent stress urinary incontinence during pregnancy and one year after delivery; its prevalence, risk factors and impact on quality of life in Taiwanese women: an observational cohort study. Taiwanese J Obstetrics Gynecol. 2018;57(3):340–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjog.2018.04.003.

Bedretdinova D, Fritel X, Panjo H, Ringa V. Prevalence of female urinary incontinence in the general population according to different definitions and study designs. Eur Urol. 2016;69(2):256–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2015.07.043.

Islam RM, Oldroyd J, Rana J, Romero L, Karim MN. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in community-dwelling women in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-03992-z.

Almousa S, Bandin van Loon A. The prevalence of urinary incontinence in nulliparous adolescent and middle-aged women and the associated risk factors: a systematic review. Maturitas. 2018;107:78–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.10.003.

Teixeira RV, Colla C, Sbruzzi G, Mallmann A, Paiva LL. Prevalence of urinary incontinence in female athletes: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29(12):1717–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-018-3651-1.

Cetinel B, Demirkesen O, Tarcan T, Yalcin O, Kocak T, Senocak M, et al. Hidden female urinary incontinence in urology and obstetrics and gynecology outpatient clinics in Turkey: what are the determinants of bothersome urinary incontinence and help-seeking behavior? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(6):659–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-006-0223-6.

Hagglund D, Walker-Engstrom ML, Larsson G, Leppert J. Quality of life and seeking help in women with urinary incontinence. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80(11):1051–5.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–12. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.283.15.2008.

(CPH) CPH (2020) Data Extraction and Assessment Template. https://ph.cochrane.org/review-authors.

Munn Z, Moola S, Riitano D, Lisy K. The development of a critical appraisal tool for use in systematic reviews addressing questions of prevalence. Int J health policy Manag. 2014;3(3):123–8. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2014.71.

Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):147–53. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054.

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors) (2019) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019). www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

Hvidman L, Hvidman L, Foldspang A, Mommsen S, Bugge Nielsen J. Correlates of urinary incontinence in pregnancy. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2002;13(5):278–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001920200061.

Herath INS, Balasuriya A, Sivayogan S. Physical and psychological morbidities among selected antenatal females in Kegalle district of Sri Lanka: a cross sectional study. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;37(7):849–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443615.2017.1306697.

Wesnes SL, Rortveit G, Bø K, Hunskaar S. Urinary incontinence during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(4):922–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.Aog.0000257120.23260.00.

Balik G, Guven ES, Tekin YB, Senturk S, Kagitci M, Ustuner I, et al. Lower urinary tract symptoms and urinary incontinence during pregnancy. Lower Urin Tract Sympt. 2016;8(2):120–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/luts.12082.

Bø K, Pauck Øglund G, Sletner L, Mørkrid K, Jenum A. The prevalence of urinary incontinence in pregnancy among a multi-ethnic population resident in Norway. BJOG. 2012;119(11):1354–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03435.x.

Okunola TO, Olubiyi OA, Omoya S, Rosiji B, Ajenifuja KO. Prevalence and risk factors for urinary incontinence in pregnancy in Ikere-Ekiti, Nigeria. Neurourol Urodyn. 2018;37(8):2710–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.23726.

Solans-Domènech M, Sánchez E, Espuña-Pons M. Urinary and anal incontinence during pregnancy and postpartum: incidence, severity, and risk factors. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(3):618–28. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d04dff.

Abdullah B, Ayub SH, Mohd Zahid AZ, Noorneza AR, Isa MR, Ng PY. Urinary incontinence in primigravida: the neglected pregnancy predicament. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;198:110–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.01.006.

Hojberg KE, Salvig JD, Winslow NA, Lose G, Secher NJ. Urinary incontinence: prevalence and risk factors at 16 weeks of gestation. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106(8):842–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08407.x.

Nigam A, Ahmad A, Gaur D, Elahi A, Batra S. Prevalence and risk factors for urinary incontinence in pregnant women in late third trimester. IJRCOG. 2016;5(7):2187–91.

Avery K, Donovan J, Peters TJ, Shaw C, Gotoh M, Abrams P. ICIQ: a brief and robust measure for evaluating the symptoms and impact of urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2004;23(4):322–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.20041.

Brown SJ, Donath S, MacArthur C, McDonald EA, Krastev AH. Urinary incontinence in nulliparous women before and during pregnancy: prevalence, incidence, and associated risk factors. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(2):193–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-009-1011-x.

Daly D, Clarke M, Begley C. Urinary incontinence in nulliparous women before and during pregnancy: prevalence, incidence, type, and risk factors. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29(3):353–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-018-3554-1.

Sharma JB, Aggarwal S, Singhal S, Kumar S, Roy KK. Prevalence of urinary incontinence and other urological problems during pregnancy: a questionnaire based study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;279(6):845–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-008-0831-0.

Raza-Khan F, Graziano S, Kenton K, Shott S, Brubaker L. Peripartum urinary incontinence in a racially diverse obstetrical population. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17(5):525–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-005-0061-y.

Lambert DM, Marceau S, Forse RA. Intra-abdominal pressure in the morbidly obese. Obes Surg. 2005;15(9):1225–32. https://doi.org/10.1381/096089205774512546.

Mørkved S, Salvesen KA, Bø K, Eik-Nes S. Pelvic floor muscle strength and thickness in continent and incontinent nulliparous pregnant women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2004;15(6):384–9; discussion 390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-004-1194-0.

van Veelen A, Schweitzer K, van der Vaart H. Ultrasound assessment of urethral support in women with stress urinary incontinence during and after first pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(2 Pt 1):249–56. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000000355.

Swenson CW, Kolenic GE, Trowbridge ER, Berger MB, Lewicky-Gaupp C, Margulies RU, et al. Obesity and stress urinary incontinence in women: compromised continence mechanism or excess bladder pressure during cough? Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(9):1377–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-017-3279-6.

MacLennan AH, Taylor AW, Wilson DH, Wilson D. The prevalence of pelvic floor disorders and their relationship to gender, age, parity and mode of delivery. Bjog. 2000;107(12):1460–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11669.x.

Stach-Lempinen B, Kujansuu E, Laippala P, Metsänoja R. Visual analogue scale, urinary incontinence severity score and 15 D--psychometric testing of three different health-related quality-of-life instruments for urinary incontinent women. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2001;35(6):476–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/003655901753367587.

Boonstra AM, Schiphorst Preuper HR, Balk GA, Stewart RE. Cut-off points for mild, moderate, and severe pain on the visual analogue scale for pain in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain. 2014;155(12):2545–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2014.09.014.

Jean-Michel M, Kroes J, Marroquin GA, Chau EM, Salafia CM, Mikhail M. Urinary incontinence in pregnant young women and adolescents: an unrecognized at-risk group. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018;24(3):232–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/spv.0000000000000445.

Oliveira C, Seleme M, Cansi PF, Consentino RF, Kumakura FY, Moreira GA. Berghmans B (2013) urinary incontinence in pregnant women and its relation with socio-demographic variables and quality of life. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 1992;59(5):460–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ramb.2013.08.002.

Spellacy C. Urinary incontinence in pregnancy and puerperium. JOGNN. 2001;30(6):634–41.

Tanawattanacharoen S, Thongtawee S. Prevalence of urinary incontinence during the late third trimester and three months postpartum period in King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital. J Med Assoc Thail. 2013;96(2):144–9.

Thomason AD, Miller JM, Delancey JO. Urinary incontinence symptoms during and after pregnancy in continent and incontinent primiparas. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(2):147–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-006-0124-8.

Papanicolaou S, Hunskaar S, Lose G, Sykes D. Assessment of bothersomeness and impact on quality of life of urinary incontinence in women in France, Germany, Spain and the UK. BJU Int. 2005;96(6):831–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05722.x.

Kinchen KS, Burgio K, Diokno AC, Fultz NH, Bump R, Obenchain R. Factors associated with women’s decisions to seek treatment for urinary incontinence. J Women’s Health (Larchmt). 2003;12(7):687–98. https://doi.org/10.1089/154099903322404339.

Mason L, Glenn S, Walton I, Hughes C. Women’s reluctance to seek help for stress incontinence during pregnancy and following childbirth. Midwifery. 2001;17(3):212–21. https://doi.org/10.1054/midw.2001.0259.

Burgio KL, Zyczynski H, Locher JL, Richter HE, Redden DT, Wright KC. Urinary incontinence in the 12-month postpartum period. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(6):1291–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obstetgynecol.2003.09.013.

Gartland D, MacArthur C, Woolhouse H, McDonald E, Brown SJ. Frequency, severity and risk factors for urinary and faecal incontinence at 4 years postpartum: a prospective cohort. Bjog. 2016;123(7):1203–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13522.

Woodley SJ, Lawrenson P, Boyle R, Cody JD, Morkved S, Kernohan A, et al. Pelvic floor muscle training for preventing and treating urinary and faecal incontinence in antenatal and postnatal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;5:Cd007471. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007471.pub4.

Adaji SE, Shittu OS, Bature SB, Nasir S, Olatunji O. Suffering in silence: pregnant women’s experience of urinary incontinence in Zaria, Nigeria. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;150(1):19–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.02.008.

Balik G, Güven ES, Tekin YB, Şentürk Ş, Kağitci M, Üstüner I, et al. Lower urinary tract symptoms and urinary incontinence during pregnancy. Low Urin Tract Symptoms. 2016;8(2):120–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/luts.12082.

Bekele A, Adefris M, Demeke S. Urinary incontinence among pregnant women, following antenatal care at University of Gondar Hospital, north West Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):333. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1126-2.

Beksac AT, Aydin E, Orhan C, Karaagaoglu E, Akbayrak T. Gestational urinary incontinence in nulliparous pregnancy- a pilot study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(8):Qc01–qc03. https://doi.org/10.7860/jcdr/2017/25572.10333.

Bo K, Oglund G, Sletner L, Morkrid K, Jenum A. The prevalence of urinary incontinence among a multi-ethnic population resident in Norway. BJOG. 2012;119:1354–60.

Chan SS, Cheung RY, Yiu KW, Lee LL, Chung TK. Prevalence of urinary and fecal incontinence in Chinese women during and after their first pregnancy. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(9):1473–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-012-2004-8.

Dinç A. Prevalence of urinary incontinence during pregnancy and associated risk factors. Low Urin Tract Symptoms. 2018;10(3):303–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/luts.12182.

Dolan LM, Walsh D, Hamilton S, Marshall K, Thompson K, Ashe RG. A study of quality of life in primigravidae with urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2004;15(3):160–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-004-1128-x.

Groutz A, Gordon D, Keidar R, Lessing JB, Wolman I, David MP, et al. Stress urinary incontinence: prevalence among nulliparous compared with primiparous and grand multiparous premenopausal women. Neurourol Urodyn. 1999;18(5):419–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1520-6777.

Hansen BB, Svare J, Viktrup L, Jorgensen T, Lose G. Urinary incontinence during pregnancy and 1 year after delivery in primiparous women compared with a control group of nulliparous women. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31(4):475–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.21221.

Huebner M, Antolic A, Tunn R. The impact of pregnancy and vaginal delivery on urinary incontinence. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010;110(3):249–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.04.019.

Kocaoz S, Talas MS, Atabekoglu CS. Urinary incontinence in pregnant women and their quality of life. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(23–24):3314–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03421.x.

Kok G, Seven M, Guvenc G, Akyuz A. Urinary incontinence in pregnant women: prevalence, associated factors, and its effects on health-related quality of life. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2016;43(5):511–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/won.0000000000000262.

Liang CC, Chang SD, Lin SJ, Lin YJ. Lower urinary tract symptoms in primiparous women before and during pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285(5):1205–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-011-2124-2.

Luo D, Chen L, Yu X, Ma L, Chen W, Zhou N, et al. Differences in urinary incontinence symptoms and pelvic floor structure changes during pregnancy between nulliparous and multiparous women. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3615. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.3615.

Mallah F, Tasbihi P, Navali N, Azadi A. Urinary incontinence during Pregnance and postpartum incidence, severity and risk factors in Alzahra and Taleqani hospitals in Tabriz, Iran 2011-2012. IJWHR. 2014;2(3):178–85.

Marshall K, Thompson KA, Walsh DM, Baxter GD. Incidence of urinary incontinence and constipation during pregnancy and postpartum: survey of current findings at the rotunda lying-in hospital. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105(4):400–2. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10123.x.

Martin-Martin S, Pascual-Fernandez A, Alvarez-Colomo C, Calvo-Gonzalez R, Muñoz-Moreno M, Cortiñas-Gonzalez JR. Urinary incontinence during pregnancy and postpartum. Associated risk factors and influence of pelvic floor exercises. Arch Esp Urol. 2014;67(4):323–30.

Martínez Franco E, Parés D, Lorente Colomé N, Méndez Paredes JR, Amat Tardiu L. Urinary incontinence during pregnancy. Is there a difference between first and third trimester? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;182:86–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.08.035.

Martins G, Soler ZA, Cordeiro JA, Amaro JL, Moore KN. Prevalence and risk factors for urinary incontinence in healthy pregnant Brazilian women. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(10):1271–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-010-1185-2.

Morkved S, Bo K. Prevalence of urinary incontinence during pregnancy and postpartum. Int Urogynecol J. 1999;10:394–8.

Rocha J, Brandão P, Melo A, Torres S, Mota L, Costa F (2017) [assessment of urinary incontinence in pregnancy and postpartum: observational study]. Acta med port 30 (7-8):568-572. https://doi.org/10.20344/amp.7371.

Rogers RG, Ninivaggio C, Gallagher K, Borders AN, Qualls C, Leeman LM. Pelvic floor symptoms and quality of life changes during first pregnancy: a prospective cohort study. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(11):1701–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-017-3330-7.

Sottner O, Zahumenski J, Krcmar M, Brtnicka H, Kolarik D, Driak D, et al. Urinary incontinence in a Group of Primiparous Women in the Czech Republic. Gynecol Obstet Investig. 2006;62:33–47.

Valeton CT, do Amaral VF (2011) Evaluation of urinary incontinence in pregnancy and postpartum in Curitiba mothers program: a prospective study. Int Urogynecol J 22 (7):813–818. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-011-1365-8.

Zhu L, Li L, Lang JH, Xu T. Prevalence and risk factors for peri- and postpartum urinary incontinence in primiparous women in China: a prospective longitudinal study. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23(5):563–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-011-1640-8.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the following persons for their support and cooperation in conducting the study: Bjorn Winkens, Department of Methodology and Statistics, Maastricht University, and Mrs. Julia J. Herbert, MSc, for checking the English language. This study was supported by grant number 80-84300-98-72001 from The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Search strategy for PubMed:

(((((((((((((((((((pregnancy[MeSH Terms]) OR pregnancy[Title/Abstract]) OR pregn*) OR prepartum[Title/Abstract]) OR ‘pre-partum’[Title/Abstract]) OR ‘pre partum’[Title/Abstract]) OR peripartum[Title/Abstract]) OR ‘peri-partum’[Title/Abstract]) OR ‘peri partum’[Title/Abstract]) OR nulliparous[Title/Abstract]) OR primiparous[Title/Abstract]) OR primigrav*[Title/Abstract]) OR primipar*[Title/Abstract]) OR multiparous[Title/Abstract]) OR multigrav*[Title/Abstract]) OR multipar*[Title/Abstract])) AND (((((((((((‘urinary incontinence’[MeSH Terms]) OR urinary incontinence title/abstract) OR ‘urine loss’[Title/Abstract]) OR ‘pelvic floor disorders’[MeSH Terms]) OR ‘pelvic floor disorders’[Title/Abstract]) OR ‘pelvic floor dysfunctions’[Title/Abstract])) OR incontinence[Title/Abstract])) OR ‘leaking urine’[Title/Abstract]))) AND ((((((((((((prevalence[MeSH Terms]) OR prevalence[Title/Abstract]) OR epidemiology[MeSH Terms]) OR epidemiology[Title/Abstract]) OR quality of life[MeSH Terms]) OR ‘quality of life’[Title/Abstract]) OR bother*[Title/Abstract]) OR bothersomeness[Title/Abstract]))))))

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moossdorff-Steinhauser, H.F.A., Berghmans, B.C.M., Spaanderman, M.E.A. et al. Prevalence, incidence and bothersomeness of urinary incontinence in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J 32, 1633–1652 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04636-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04636-3