Abstract

In this paper we explore the association between cost stickiness and firm value. Using a large sample of U.S. data, we find a robust negative relationship between cost stickiness and firm value. We then explore whether the resource adjustment, managerial expectations, and agency theories of cost stickiness affect the negative relation and find support for the managerial expectation and agency theories. Furthermore, we find evidence that the detrimental impact of cost stickiness on firm value is mediated partially through the cost of equity and cash flow channels. Further investigation suggests that the adverse effects of cost stickiness on firm value is stronger in the presence of high information asymmetry. We enrich the cost management literature by integrating cost stickiness with corporate finance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Cost stickiness is premised on the notion that costs do not behave linearly in response to changes in activity level (Cooper & Kaplan, 1992; Noreen, 1991) but, instead, depend on manager’s deliberate resource adjustment decisions. This is in contrast to traditional cost accounting, which considers fixed costs as resources not amenable to short-term adjustments, whereas variable costs can be adjusted easily in the short-term. However, in reality, resources fall along a spectrum and require managerial judgement regarding whether and when to adjust resources in response to changes in activity levels (Banker et al., 2018). Initial empirical evidence supporting the existence of cost stickiness was provided by Anderson et al. (2003), who document that selling, general and administrative (SGA) costs rise more when sales increase but decrease less when sales decrease.

While a plethora of studies have examined the determinants of cost stickiness (see Banker et al., 2018; Ibrahim et al, 2022 for comprehensive reviews), surprisingly little evidence exists on the implications of such cost stickiness. The most notable work is by Weiss (2010), who documents a positive relationship between cost stickiness and the analyst forecast error. According to Weiss (2010, p. 1442), firms with higher cost stickiness demonstrate greater declines in earnings, because “……stickier costs result in a smaller cost adjustment when activity level declines and, therefore, lower cost savings, [which] result in a greater decrease in earnings. This greater decrease in earnings when the activity levels fall increases the variability of the earnings distribution, resulting in less accurate earnings predictions.” Weiss (2010) also finds that firms with stickier costs have less analyst coverage, and investors rely less on the realized earnings of such firms because of their lower predictive power. Ciftci et al. (2016), reveal that analysts are unable to recognize and incorporate the ‘sticky’ nature of costs in their forecasts: a feature that increases error in earnings prediction. In addition, cost stickiness has been found to increase credit risk. Firms encounter increased default and credit risk, owing to higher earnings and asset volatility stemming from cost stickiness (Homburg et al., 2016). Similar to analysts, managers are also unable to incorporate cost stickiness, as Ciftci and Salama (2018) show that cost stickiness leads to higher management earnings forecast errors. He et al. (2020) find that firms with greater cost stickiness pay less dividend: a finding consistent with the argument that stickier firms will be unable to sustain high dividend payouts in the long run. In this paper we examine the association between cost stickiness and firm value, and the mediating effect of the cost of equity capital and cash flows on the relationship, if any.

We investigate this question for at least three important reasons. First, it is not clear ex-ante whether the findings documented by Weiss (2010) will mean that firms with more cost stickiness will have lower market value. The existing research on cost stickiness has proposed three potential explanations grounded on resource adjustment, managerial expectations, and agency arguments (Anderson et al., 2003; Banker et al., 2014b; Chen et al., 2012). We argue that the relationship between cost stickiness and firm value could vary, depending on which of these arguments dominates. Second, costs are a core driver of firm profitability and, consequently, firm value. Therefore, it is important to understand how cost stickiness affects firm value, since the maximization of firm value is considered to be one of the primary objectives of the firm (Jensen & Meckling, 1976). Third, Weiss (2010) uses three-day cumulative abnormal returns (CAR) surrounding the earnings announcement dates to proxy for market response to quarterly earnings announcements. However, such a short window test may fail to capture managerial resource adjustment decisions. This is because companies make resource adjustment decisions throughout the year, and the chosen short window may not coincide with any significant resource adjustment decisions. Hence, taking a longer time span of one year could ensure that resource adjustment decisions during the entire year are incorporated into firm value, thereby overcoming the limitations of the short window test to some extent.

During declining sales, retention of slack resources decreases the present value of sales, and increases the opportunity cost of keeping unused resources, resulting in decreased firm profitability. Therefore, we expect a negative association between cost stickiness and firm value. Investors make their investment decisions based primarily on the financial health of a firm, and this is determined by the future earnings and cash flow potential of the firm. Investors consider current earnings as a key firm performance indicator, as it can reliably predict future earnings (Finger, 1994; Nissim & Penman, 2001), future cash flows (Barth et al., 2001; Dechow et al., 1998), and firm equity performance (Dechow, 1994) or, in other words, the future wealth of the firm (Callen et al., 2009). More volatile earnings, and increased analysts’ earnings forecast errors stemming from greater cost stickiness when sales decline, increase investors’ investment risk and decreases analyst following (Weiss, 2010). An increase in investment risk requires investors to demand a higher return on their investments, thereby, increasing the cost of equity for the firm. Furthermore, retaining slack resources when sales decline incurs adjustment costs: an effect that also reduces cash flows. Since, cost of equity and future cash flows are the components of firm value, we further propose that the association between cost stickiness and firm value is mediated by these two components.

Using a sample of 85,521 firm-year observations of U.S. listed firms spanning the period from 1982 to 2016, we document that operating cost stickiness reduces firm value. In terms of economic magnitude, a one-standard-deviation increase in cost stickiness decreases firm value by 2.44 percent relative to its mean. Further investigation suggests that this detrimental relationship between cost stickiness and firm value exists owing to investor recognition of agency problem associated with the retention of slack resources. Empirical results also suggest that retention of slack resources in the event of a sales decline is detrimental for firms when managers are pessimistic about future demand. Further, we find evidence that this negative relation between cost stickiness and firm value is partially mediated through both the cost of equity and the cash flow channels, as the direct effect of cost stickiness on firm value accounts for the bulk of the total effect. Finally, we find that the adverse effects of cost stickiness on firm value become more pronounced for firms with high information asymmetry. The negative relationship between cost stickiness and firm value also holds for alternative measures of cost stickiness and cost components.

Understanding the implications of cost stickiness is important for managers as well as investors. Managers need to be aware of how their deliberate resource adjustment decisions could affect overall financial stability, cost of equity and, consequently, firm value. Feedback from the market could enable them to be more efficient in resource management. From the perspective of the investors, it is important that they understand the rationale behind retaining slack resources. A myopic consideration, i.e., failure to recognize the rationale for retaining resources to minimize resource adjustment costs, might lead them to conclude erroneously that retaining unutilised resources is detrimental to firm value. Therefore, our study provides a timely contribution to the limited research on the implications of cost stickiness. Our study also contributes to the line of research that integrates management accounting (cost stickiness) with financial accounting (firm value) and corporate finance (cost of equity and cash flow). Although Weiss (2010) concludes that investors take cost stickiness into consideration, our investigation provides the insight that cost stickiness leads to lower cash flows and investor demands for higher returns, both of which are detrimental to firm value.

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 reviews the related literature and develops the hypotheses. The research methods and sample selection procedure are described in Sect. 3. Descriptive statistics and test results are reported in Sect. 4. Section 5 reports various robustness tests. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2 Literature review and hypotheses development

2.1 Cost stickiness and firm value

A rational economic assumption is that one of the primary objectives of a manager is to create shareholder wealth, and one way to achieve that is through maximizing profit. To generate and sustain profits to maximize shareholder wealth, efficient cost management is crucial for managers; therefore, understanding cost behaviour and research related to cost stickiness have gained popularity in recent times. A manager’s task is to create shareholder wealth by engaging in activities and implementing strategies that allow the warranted market value of equity capital invested in the firm by the shareholders to exceed the book value of equity (Varaiya et al., 1987). A firm’s warranted market value of equity is investors’ perceived assessment of how effectively and efficiently the manager has used the invested capital and, thus, whether firm value will be created or destroyed depends on managerial decisions on efficient utilization of the firm’s resources, including cost management. Extant literature document that firms undergoing a declining performance reduce costs significantly in order to stabilize business operations and maintain profitability (Bailey & Szerdy, 1988; Grinyer & McKiernan, 1990; Hambrick & Schecter, 1983; Robbins & Pearce, 1992). In addition, investors consider current earnings as a key firm performance indicator that has been found to predict future earnings reliably (Finger, 1994; Nissim & Penman, 2001), as well as future cash flows (Barth et al., 2001; Dechow et al., 1998) and firm equity performance (Dechow, 1994) or, in other words, the future wealth of the firm (Callen et al., 2009). It, therefore, follows that cost behaviour that affects accounting earnings profoundly, should be related to firm value.

Weiss (2010) finds that firms with sticky costs tend to have volatile earnings, and analysts fail to incorporate the ‘sticky’ nature of costs; thereby, making their forecasts less accurate. Moreover, Weiss (2010) documents that investors are unlikely to rely on the realized earnings of firms with high-cost stickiness because of their lower predictive power. Similar to analysts, managers are also unable to incorporate cost stickiness in their forecasts, and this failure results in higher management earnings forecast errors (Ciftci & Salama, 2018). Hartlieb and Loy (2022) document that cost stickiness has a negative impact on garbling component of income smoothing. Habib and Costa (2022) document a positive association between cost stickiness and future stock price crash risk. Agarwal (2022) finds that cost stickiness reduces the quality of information available to investors and causes stock price delay. Firms encounter increased default and credit risk, owing to higher earnings and asset volatility stemming from cost stickiness (Homburg et al., 2016). He et al. (2020) document that firms with high resource adjustment costs and greater cost stickiness pay less dividend because, in the long run, such firms will be unable to continue paying a sustainable level of dividend. Therefore, retaining slack resources during declining demand decreases the present value of sales, increases the opportunity cost of keeping unused resources, decreases firm profitability and, thereby, affects firm value adversely. We, therefore, hypothesize as follows:

H1

There is a negative relation between cost stickiness and firm value, ceteris paribus.

Investigating the association between cost stickiness and firm value without accounting for the drivers of such an association, provides only a partial picture. Thus, to unfold what triggers the empirical relationship hypothesized in H1 above, we condition H1 on the theory driving the cost behaviour of a firm. Managers’ decisions related to resource adjustment during declining demand is based on resource adjustment theory, managerial expectation theory and agency theory. Resource adjustment theory is based on the notion that many costs arise from managers’ deliberate resource commitment decisions. Once committed, it is not easy to scale back resources without incurring some kind of adjustment cost. For instance, labour adjustment costs have been found to induce cost stickiness (Banker et al., 2013; Golden et al., 2020). Managers tend to enter into contracts for resources, which are costly to renegotiate; thus, when demand falls, managers are bound to retain those slack resources, because discarding them would incur obligatory costs such as severance payments (Calleja et al., 2006). Therefore, if rational investors are able to incorporate such high ‘adjustment costs’ into their valuations, then firm value should not necessarily be affected adversely during periods of sales decline. However, according to Agarwal (2022) investors are unlikely to have access to managerial rationale behind retaining slack resources and information on high ‘adjustment costs’. Therefore, investors will penalize firms for retaining slack resources as this will lower firm’s current profitability and will make earnings more volatile, thereby affecting firm value adversely. We, therefore, hypothesize as follows:

H2A

Cost stickiness may affect firm value adversely when the resource adjustment cost is high, ceteris paribus.

Managerial expectation theory posits that when managers are optimistic (pessimistic) about future demand, they are likely to retain (reduce) slack resources in the event of declining demand (Banker & Byzalov, 2014; Banker et al., 2014a; Venieris et al., 2015). Optimistic managers consider a declining demand as ‘temporary’ and prefer to retain slack resources to minimize the downward adjustment costs. If investors are concerned about long-term value creation by the company, then the retention of slack resources by optimistic managers during declining demand should not necessarily lead to a decrease in firm value. However, if managers are pessimistic about the future demand, then retaining slack resources is likely to have an adverse impact on firm value. As discussed before, maintaining slack resources during periods of sales decline would decrease the present value of sales and increase the opportunity cost of keeping unutilized resources: factors that would contribute to a reduction in profit and, hence, firm value. We, therefore, hypothesize as follows:

H2B

Cost stickiness affects firm value adversely when managers are pessimistic, ceteris paribus.

Agency theory predicts a negative relationship between cost stickiness and firm value. The agency problem occurs because of a misalignment of interests between shareholders and managers. An implication of the agency problem is that managers engage in empire-building activities, e.g., growing the firm beyond its optimal size by retaining unutilized resources for status, power, compensation, and prestige (see, e.g., Chen et al., 2012; Hope & Thomas, 2008; Jensen, 1986; Masulis et al., 2007; Stulz, 1990). Prior studies have documented that managers with empire-building tendencies are likely to add excessive resources when sales increase and are unlikely to reduce unutilized resources when demand falls, resulting in cost stickiness (Banker et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2012). Chen et al. (2012) document a positive relation between the agency problem and cost stickiness. Self-serving managers might be less tempted to discard unused resources, because such a decision reduces their chance of maximizing private benefits. However, such activity is likely to be value-destroying for the firm. We, therefore, hypothesize as follows:

H2C

Cost stickiness affects firm value adversely for firms with pronounced agency problem, ceteris paribus.

2.2 Mediating effect of cost of equity and cash flow on cost stickiness and firm value

So far, we have discussed the plausible direct relationship between cost stickiness and firm value. A related issue to be examined is whether this direct relation between cost stickiness and firm value is mediated through the cost of equity and cash flow channels. Since firm value consists of cost of equity and expected future cash flow components (Chen et al., 2010; Penman, 2011, 2016; Plumlee et al., 2015), investigating the mediating effect of these two components would provide insights into the relationship between cost stickiness and firm value.

Equity valuation involves discounting expected payoffs (free cash flows) (Penman, 2011). Realizations of future cash flows are plagued with fundamental uncertainties. This type of uncertainty is related to a firm’s specific business model, type of business, organizational structure, changes in competitive landscape, impacts of new product launches, regulatory change, and shifts in macro-economic conditions (Chen et al., 2008). As will be discussed below, volatile earnings stemming from more cost stickiness, increase cash flow uncertainties and, hence, investors need to be compensated through a higher rate of return (discount rate). Thus, both cash flow news (free cash flow) and return news (discount rate) become the appropriate channels to further examine the association between cost stickiness and firm value.

Cost stickiness increases earnings volatility, analysts’ forecast error (Ciftci et al., 2016; Weiss, 2010), credit risk (Homburg et al., 2016) and decreases analysts’ coverage: precursors of heightened investment risk. Such heightened risk, in turn, requires investors to demand a higher return from their investments and, thereby, increases the firm-level cost of equity capital. Therefore, the negative relation between firm value and cost stickiness may be attributed to an increase in discount rate holding firm cash flows constant, as investors may consider such resource adjustment decision to be inefficient and risky. With respect to future cash flows, holding onto unutilized resources during the period of declining demand incurs cost. Many such obligations, for instance, wages to workers, maintenance and repair costs of equipment, rents on leased equipment and storage/warehouse fees, have to be paid during the period with cash to avoid contractual violations. Therefore, a decline in cash during a period of declining sales would affect firm value adversely. Furthermore, cost stickiness makes the accurate prediction of future cash flows a difficult task and this, again, affects firm value adversely, since investors consider future cash flows when making investment decisions. Moreover, volatile cash flows also create uncertainty for investors regarding future dividend pay-outs. Thus, we hypothesize as follows:

H3

The association between cost stickiness and firm value postulated in H1 is mediated through the cost of equity and cash flow channels.

3 Research design

3.1 Empirical model

To test the relation between cost stickiness and firm value (H1), we adopt the following cross-sectional regression model:

We use Tobin’s Q (TOBINQ)Footnote 1 for the year t as our proxy for firm value, following previous literature (e.g., Henry, 2008; Jin & Jorion, 2006; Konijn et al., 2011; Maury & Pajuste, 2005; Villalonga & Amit, 2006). We measure TOBINQ as book value of assets plus market value of equity minus book value of equity minus deferred tax, scaled by the book value of assets. This is a widely used definition of Tobin’s Q (Gompers et al., 2003; Jiao, 2010; Kaplan & Zingales, 1997). We acknowledge that there are more sophisticated ways to measure Tobin’s Q (Perfect & Wiles, 1994), however, it is evident from prior studies that there is a high correlation between our measure of Tobin’s Q and more complex ones (Chung & Pruitt, 1994; Jiao, 2010). We control for firm risk (RISK), firm size (SIZE), leverage (LEV), firm profitability (PROFIT), firm growth or investment opportunities (GROWTH) and institutional ownership (IOWN). All variables are defined in the Appendix.

The main independent variable in our analysis is OC_STICKY. We use the firm-level cost sticky measure developed by Weiss (2010), as this measure is more appropriate for research examining the effect of cost stickiness (Banker & Byzalov, 2014). Weiss (2010) defines cost stickiness for firm i in quarter q (STICKYi,q) as the difference in the slope of the cost function between the two most recent quarters from quarter q-3 to q, such that sales decrease in one quarter and sales increase in the other.

where Ť (Ţ) is the most recent of the last four quarters with an increase (decrease) in sales, ΔCOST = COSTi,q-COSTi,q-1 and ΔSALES = SALEi,q-SALEi,q− 1. We obtain OC_STICKY by taking the mean of STICKYi,q values for firm i and in year t following Kim et al. (2019) and Costa and Opare (2022). We multiply Weiss’s (2010) original measure by -1 following Rouxelin et al. (2018) and Golden et al. (2020), so that higher values imply more cost stickiness. H1 predicts a negative and significant coefficient on OC_STICKYi,t. We take operating costs (OC) (Compustat data item SALEQ minus IBQ) because it is more comprehensive, as it includes costs related to both internal and external financing (Costa et al., 2021). Moreover, operating costs are incurred for everyday business operations, and failure to meet these contractual obligations could lead to early bankruptcy (Chen et al., 2019). In robustness tests (Sect. 4.3), we use the stickiness of selling, general and administrative cost (SGA_STICKY) and cost of goods sold (COGS_STICKY) as alternative cost components.

3.2 Resource adjustment cost, managerial expectation and agency problem proxies

We include (i) asset intensity (AIN), and (ii) workers’ skill level (SKILL) as two proxies for resource adjustment costs. AIN is measured as the total assets divided by the sales for year t. Based on the median value of AIN, we create two sub-groups with the high (low) AIN group representing firms incurring high (low) resource adjustment costs. Workers differ in their skill levels. For instance, a high-skill worker such as an engineer has an input to production different from that of a low-skill worker, such as an assembly-line worker. Thereby, labour is a heterogeneous factor of production. High-skilled workers tend to conduct difficult jobs, making them costly to replace; whereas, low-skilled workers jobs involve routine and relatively easy tasks, making them less costly to replace (Belo et al., 2017; Ghaly et al., 2017). We, therefore, include SKILL as another proxy for resource adjustment cost. SKILL is a dummy variable coded 1 for firm-year observations with above-median SKILL scores, and zero otherwise.Footnote 2

For managerial expectation we use two proxies, namely, (i) investor sentiment index (CCI) and (ii) business cycle measure (OECD). An external proxy for managerial expectation, we use CCI which is the consumer confidence index developed by Michigan Consumer Research Center (MCRC). CCI is a widely used measure of investor sentiment (Bergman and Roychowdhury, 2008; Lemmon & Portniaguina, 2006). MCRC administers opinion surveys to households around U.S. to gauge perceptions on personal financial welfare, on countrywide financial welfare, and on consumer spending. Responses to the monthly survey’s questions are combined to form an overall measure of sentiment. A higher (lower) value of CCI indicates consumer optimism (pessimism) about the overall state of the economy. We use the OECD Composite Leading Indicators (CLI), a macroeconomic proxy to measure managerial expectation.Footnote 3 A country CLI comprises a set of component series selected from a wide range of key short-term economic indicators. During recession (expansion) managers tend to be pessimistic (optimistic) about future demand.

We deploy two proxies for the agency problem, namely, (i) asset utilization ratio i.e., sales-to-assets (STA), and (ii) distracted institutional shareholders (DSHAR). As elucidated in Sect. 2.1, one of the consequences of the agency problem is managers’ tendency to engage in empire-building. Such managers are likely to overspend in the form of capital expenditure or acquire business to build an empire. Therefore, we have used STA to measure the empire-building tendency of managers (Ang et al., 2000; Fauver & Naranjo, 2010). STA, an efficiency ratio, measures how efficiently a manager utilizes assets under his/her control. The rationale behind using this ratio to proxy for the agency problem is that a low ratio implies that the manager has, for example, purchased unproductive assets and/or consumed excessive perquisites. Firm-year observations with below (above)-median STA are considered high (low) agency problem groups. Our second proxy for agency problem is institutional investor distraction. Investor attention plays a monitoring role in keeping managers’ interests aligned with firms’ goals. Kempf et al. (2017) constructed a firm-level shareholder “distraction” measure to capture the agency problem. The authors find that firms with distracted shareholders tend to make value-destroying M&A decisions. Additionally, such firms are more likely to cut dividends, and unlikely to dismiss poor performing CEOs: actions that increase agency costs for shareholders.Footnote 4 Firm-year observations with DSHAR higher (lower) than the median are considered high (low) agency problem groups.

3.3 Mediating effect variables

To test the mediating effects of cost of equity and cash flows on the association between cost stickiness and firm value (H3), we follow the mediation test approach of Baron and Kenny (1986). Following Baron and Kenny (1986), we use the following four steps to establish these mediation channels (Eqs. (3a)–(3c)). First, we show that variations in the independent variable (i.e., OC_STICKY, in our study) are correlated with the dependent variable (i.e., TOBINQ; Eq. (3a)), to confirm the possibility that a mediation effect is present. Second, we show how variations in the independent variable (i.e., OC_STICKY) account for variations in the mediators (Eq. (3b)). Third, we show that the mediators have a significant effect on the dependent variable (i.e., TOBINQ; Eq. (3c). Finally, we show that the significant relationship between OC_STICKY and TOBINQ (Eq. (3a)) either becomes insignificant after controlling for the mediators (full mediation) or that the significance level shrinks after doing so (partial mediation). In order to test the mediation effect (H3) we use the following set of equations:

where MV are the mediating variables, with MV_COEi,t being the mediating variable representing cost of equity capital, and MV_FCFi,t being the mediating variable pertaining to free cash flow (FCFi.t). Based on prior studies (Easton, 2004; El Ghoul et al., 2011; Gupta et al., 2018) we use implied approaches to estimate the cost of equity. Equation (3a) is our original baseline regression model or Eq. (1). For Eq. (3b) we include SIZE, LEV, IOWN, BETA (market beta), BTM (book-to-market value), ZSCORE (Altman’s Z-score) and DAC (discretionary accrual) as the control variables for the test using COE as the mediating channel (El Ghoul et al., 2011; Gupta et al., 2018). Owing to lack of prior literature on the determinants of free cash flow, we included the control variables used in the baseline model as some of the potential determinants of FCF. For Eq. (3c) we use the same control variables as in Eq. (1). The total effect of cost stickiness (i.e., OC_STICKY) on firm value (i.e. TOBINQ) can be decomposed into direct and indirect effects. The direct effect is \({\gamma }_{1}\) from Eq. (3c) above, while the indirect effect is α1*\({\gamma }_{2}\) for the proposed mediators. The core of the mediation effect is testing the null hypothesis H0: α1*\({\gamma }_{2}\) =0. We use a simultaneous equation model for defining and estimating the direct and indirect effects. Variables are defined in detail in the Appendix.

3.4 Sample selection

Our sample period spans from 1982 to 2016. We deliberately choose a long sample period to provide a richer analysis of the cost stickiness behaviour and firm value. We collect both yearly and quarterly financial data from Compustat, whilst the stock return data are collected from the CRSP and the institutional ownership data from Thomson Reuter’s F13 File. To estimate the implied cost of equity capital, we collect analyst forecast data from IBES. We begin with an initial sample of 413,585 firm-year observations. We then exclude 36,192 firm-year observations from the regulated industries (two-digit SIC code 48–49) and 96,226 firm-year observations from the financial institutions industry (two-digit SIC codes 60–69). Our final sample consists of 85,521 firm-year observations. Table 1, Panel A, reports the sample selection process. In the regression models, sample size varies depending on the model-specific data requirements. Firm-year observations come from a wide variety of industries, with two-digit SIC codes, 35–39 (30.13%) and 70–79 (13.83%) commanding the largest industry representation in our sample, as reported in Table 1, Panel B. To avoid the undesirable influence of outliers, we winsorize all the continuous variables at the extreme 1% of their respective distributions.

4 Empirical results and analysis

4.1 Descriptive statistics and correlation

Descriptive statistics of the baseline regression variables are reported in Panel A of Table 2. Over the study period from 1982 to 2016, the mean (median) of TOBINQ and OC_STICKY are 1.87 (1.38) and 0.05 (0.03), respectively. The average firm may be considered as moderately large (SIZE = 5.40), with moderate risk (RISK = 0.14), and moderate leverage (LEV = 0.23). On average, firms are profitable (PROFIT = 0.10) and exhibit high growth opportunities (GROWTH = 0.01).Footnote 5 Institutional ownership (IOWN) averages 39 percent. On average, sample firms use $2.08 million (median $0.92 million) assets to support each million dollars in sales. The mean (median) of STA and DSHAR are 1.17 (1.00) and 0.14 (0.14), respectively. Panel B reports the descriptive statistics of the variables used in the mediating test. The mean (median) of our mediating variables: COE_PEG, COE_MPEG and FCF are 0.11 (0.10), 0.12 (0.10) and 0.08 (0.08), respectively.

Table 3 shows the correlation between all the main variables. We find that the majority of the correlations are significant at the conventional level. From the correlation matrix it is apparent that firm value (TOBINQ) is significant and negatively correlated with OC_STICKY (− 0.021, p < 0.001). Though only suggestive of the underlying association, the highly significant negative correlation coefficient indicates that firms with higher cost stickiness have lower market values. Qtot, an alternative measure of firm value (discussed in Sect. 4.2), is positively correlated with TOBINQ (0.570, p < 0.001) and negatively correlated with OC_STICKY (− 0.021, p < 0.001). RISK, PROFIT and IOWN are positively correlated with TOBINQ; whereas, LEV and GROWTH are correlated negatively.

4.2 Regression results

Table 4 reports the OLS and firm fixed effect (FE) regression results for the association between cost stickiness and firm value for H1. To control for unobservable industry and year characteristics associated with firm value and cost stickiness, we include year and industry dummy variables in all our regression specifications. To take into account the time series and cross-sectional dependence in the error terms of our regressions, we calculate t-statistics using standard errors that are clustered by firm. Column (1) shows the OLS regression results for the relationship between OC_STICKY and TOBINQ, whilst column (2) shows the FE regression results. We find a negative and significant relationship between cost stickiness and firm value under both the OLS and the FE specifications, thereby, supporting H1. For example, the coefficient on OC_STICKY is − 0.048 (p < 0.01) in the OLS specification. In terms of economic magnitude, the estimated coefficient implies that a one-standard-deviation increase in cost stickiness decreases firm value by 2.44 percent relative to its mean (coefficient − 0.048* SD of OC_STICKY (0.95)/mean of TOBINQ (1.87)*100)).

The sign and significance of the control variables are generally consistent with prior studies (e.g., Henry, 2008; Konijn et al., 2011; Maury & Pajuste, 2005; Villalonga & Amit, 2006). From column (2), the coefficients on LEV (coefficient 0.66, p < 0.05), PROFIT (coefficient 0.68, p < 0.01), and IOWN (coefficient 1.19, p < 0.01) are positive and significant. The coefficients on SIZE (coefficient − 0.54, p < 0.01) and GROWTH (coefficient − 3.04, p < 0.01) are negative and significant. Based on prior studies (Henry, 2008), RISK should have a negative relation with firm value, although our result shows the opposite (coefficient 0.99, p < 0.01). One plausible reason could be that higher risk implies higher return which, in turn, increases firm value. From our OLS regression we find that the highest variance inflation factor (VIF) is 2.09 for the variable SIZE which is lower than the acceptable threshold of 10.00 (Costa & Habib, 2023; Marquardt, 1970; Studenmund, 2016) implying that our model does not suffer from multicollinearity.

As a robustness test, we use an alternative measure of firm value (Qtot). Results using the alternative measure of firm value (Qtot) are also reported in Table 4 (columns 3 and 4). Qtot is measured by scaling firm value by the sum of the physical and intangible capital following Peters and Taylor (2017) methodology. Results using this alternative proxy for firm value are very consistent with the TOBINQ measure. The coefficients on OC_STICKY are negative and significant in both the OLS (coefficient − 0.042, p < 0.01) and the FE (coefficient − 0.029, p < 0.01) specifications.Footnote 6 Taken together, our evidence reveals a detrimental effect of cost stickiness on firm value, supporting H1. We now test which of the three theoretical arguments developed in H2A, H2B, and H2C might explain the negative relationship.

Table 5, Panel A reports fixed effect results for H2A. For brevity, we report only the FE regression results in Table 5.Footnote 7 We hypothesized that investors are unlikely to have access to information regarding ‘adjustment costs’; and hence, are likely to penalize firms for retaining slack resources as this will lower firm’s current profitability and will make earnings more volatile, thereby affecting firm value adversely.. We find a value-destroying effect of retaining slack resources for all but the low AIN group for which the coefficient on OC_STICKY is insignificant. The coefficients are negative and significant for the high AIN group (coefficient − 0.025, p < 0.05), and the high SKILL group (coefficient − 0.034, p < 0.01).

Panel B of Table 5, reports results for the ‘managerial expectations’ arguments to test H2B. With respect to the ‘managerial expectation’ we hypothesized that retaining slack resources during declining demand and when managers are pessimistic, would affect firm value adversely. Based on the tabulated results, we find evidence supporting H2B. Our finding suggests that greater cost stickiness in the presence of managerial optimism, is not related to firm value. The coefficients on CCI (− 0.016, column 3) and OECD (− 0.018, column 5) are all insignificant.Footnote 8 However, we find evidence that investors penalize firms when managers retain slack resources, despite their pessimistic view about the future. The negative and significant coefficients on, CCI (− 0.018, p < 0.01, column 2) and OECD (− 0.026, p < 0.01, column 4) support H2B.

The FE regression results related to H2C, on whether the existence of agency problem affects the association between firm value and cost stickiness, are reported in Panel C of Table 5. For all the agency problem proxies we find evidence that cost stickiness destroys firm value for the high agency problem groups only (insignificant results for the low agency problem group). For example, the coefficient on OC_STICKY is − 0.037 (p < 0.01, column 2), and − 0.026 (p < 0.05, column 4) for STA, and DSHAR, respectively.Footnote 9 Our finding suggests that greater cost stickiness in the presence of high agency problem, is negatively related to firm value, which supports H2C.

We report the mediating test results (H3) in Table 6. Column (1) reports the regression result for Eq. (3a), whilst columns (2) to (4) report results for Eqs. (3b) and (3c). The same approach is followed in columns (5) to (7) with the only difference being in column (2), where we have used COE_PEG as the MV_COE proxy, whereas, in column (5) we have used COE_MPEG as the MV_COE proxy. Column (1) shows that the coefficient on OC_STICKY is negative and significant (coefficient − 0.028, p < 0.10), consistent with results in column (1), Table 4 (note that the coefficient is smaller than − 0.048, reported in Table 4, because of a substantial drop in the sample size). Column (2) documents a significant positive relation between cost stickiness (OC_STICKY) and COE_PEG (coefficient 0.002, p < 0.01), indicating that cost stickiness induces a higher cost of equity. This is justified because, as earnings become more volatile, investors are unable to use current earnings to predict future earnings and, therefore, require a higher return on their investments. Column (3) shows a significant negative relation between OC_STICKY and FCF (coefficient − 0.002, p < 0.01), implying that cost stickiness decreases free cash flow. A decrease in cash flow is expected when slack resources are retained in the face of declining demand because obligatory contractual payments continue to be paid off. Column (4) shows the coefficient on OC_STICKY is negative and significant but smaller in magnitude than that reported in column (1), implying a partial mediation effect.

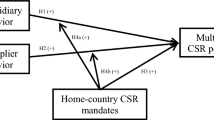

The total effect for OC_STICKY, − 0.028 (the last row of column (4)), is the effect we would have found had there been no mediator in our model. It is more meaningful to interpret the numbers from the mediation test by calculating proportions. The indirect effects through COE_PEG and FCF are − 0.008 and 0.001, respectively, with a total indirect effect of − 0.007. The proportion of the total OC_STICKY effect mediated is approximately 0.25 (total indirect effect divided by total effect), and the proportion of total OC_STICKY effect mediated through COE_PEG and FCF are 0.286 (− 0.008 divided by total effect − 0.028) and − 0.036 (0.001 divided by total effect − 0.028), respectively. Overall, we find evidence supporting H3 that the decrease in firm value due to cost stickiness is partially mediated through both the cost of equity and the free cash flow channels. Figure 1 illustrates the direct and indirect (mediated by COE and FCF) paths by a path diagram and indicates the coefficients of direct paths.

4.3 Additional test

Extant literature indicates that firms with high information asymmetry tend to suffer from lower firm value owing primarily to the adverse selection problem (e.g., Ashbaugh-Skaife et al., 2006; Drobetz et al., 2010; Fauver & Naranjo, 2010; Fosu et al., 2016; Mansi et al., 2011; Myers & Majluf, 1984). Equity investors are unable to evaluate firms’ fundamental quality owing to the presence of information asymmetry, and this results in investor demanding higher risk premiums (Botosan, 1997; Fosu et al., 2016; Gao & Zhu, 2015). Thus, owing to the high cost of equity stemming from adverse selection, firms are likely to have suboptimal investments that are detrimental for firm value (Fosu et al., 2016). Fosu et al. (2016) conjecture and find evidence using U.K. listed firms that adverse selection resulting from asymmetric information has a detrimental impact on firm value.

Managers might retain slack resources due to either high resource adjustment costs or optimistic expectations or empire-building motives. Investors are unlikely to be aware of such managerial rationales behind the retention of slack resources during declining demand. As discussed above, firms with sticky costs tend to suffer from higher volatility of both earnings and assets, and increased error in earnings prediction. Therefore, while assessing the investment opportunities, external investors encounter challenges in separating value-enhancing from value-destroying projects, owing to the existence of such information asymmetry between managers and external investors (Drobetz et al., 2010). Thus, we postulate that cost stickiness affects firm value adversely when information asymmetry is high.

We use the bid-ask spread (BA_SPREAD) to proxy for information asymmetry following prior literature (Armstrong et al., 2011; Cheng et al., 2011; Cho et al., 2013; Konijn et al., 2011). BA_SPREAD is calculated as the annual average of daily bid-ask spread scaled by the closing price for firm i in the fiscal year t. Based on the median value of BA_SPREAD, we create two sub-groups, with the high (low) BA_SPREAD group representing firms with high (low) information asymmetry.

Table 7 document that the detrimental impact of cost stickiness for firm value is more pronounced in the presence of high information asymmetry. The coefficient on OC_STICKY is insignificant for the low information asymmetry group (column 1). However, the coefficient is negative and significant for the high information asymmetry group (column 2) (coefficient − 0.038, p < 0.01). Columns (3) and (4) report the impact of cost stickiness on firm value for low and high asymmetric information-groups using Qtot as a proxy for firm value. Results using this alternative proxy for firm value are consistent with the TOBINQ measure.

5 Robustness tests

5.1 Alternative measures and cost components

In this section we perform additional analyses to check the robustness of results to alternative measures of cost stickiness, and cost components. Although the Weiss (2010) model is more appropriate for research investigating implications of cost stickiness, it has a few limitations. One of the major concerns with the Weiss (2010) approach, is that it can only be computed for firms that have had both a recent sales increase and a recent sale decrease: a criterion that results in a substantial drop in the sample size. Furthermore, Weiss’s (2010) model can only retain firms as long as the costs move in the same direction as sales. Banker and Byzalov (2014) highlight that the Weiss (2010)-based estimate could be “noisy for small sales changes due to the small denominator problem” (p. 58). Therefore, we also use the Anderson et al. (2003) model to check the robustness of our findings. Following the methodology of He et al. (2020), we estimate firm-level cost stickiness in year t by running the regression below with its previous 16 quarters of data:

where OC is operating cost, and SALE is sales revenue. DECDUM takes the value of 1 if sales in quarter q are less than sales in quarter q-1, and 0 otherwise. The coefficient β1 measures the percentage increase in OC, with a 1% increase in sales revenue. The sum of coefficients β1 and β2 measures the percentage decrease in OC with a 1% decrease in sales. β2 captures degree of cost stickiness (ABJ_OC_STICKYt). We multiply β2 by -1, so that larger values imply higher levels of cost stickiness.

Panel A, Table 8, reports the results for both the OLS and FE regressions using the Anderson et al. (2013) model. Using FE, we document in columns (2) and (4) that the coefficients on ABJ_OC_STICKYt are negative and significant for both the dependent variables TOBINQ (coefficient − 0.021, p < 0.01) and Qtot (coefficient − 0.034, p < 0.01), respectively. OLS results reported in columns (1) and (2), too, are consistent with the FE regression results. Thereby, we can conclude that our results are robust to alternative cost stickiness measure.

Although the Anderson et al. (2003) model has been widely used in the cost stickiness literature, there are certain limitations associated with it. One such shortcoming relates to the assumption that all the resources held by a firm are controllable over the short-run, i.e., one year, which is the commonly used time-period (Balakrishnan et al., 2014). However, in reality all firms have some resources with exceptionally high adjustment costs, and this inhibits resource adjustment in short-run leading to cost stickiness (Balakrishnan et al., 2014). Thus, the Anderson et al. (2003) model fails to control explicitly for cost structure. Balakrishnan et al., (2014, p. 97) suggests that “One way to avoid the non-constant cost response to activity changes is by scaling the dependent variable with lagged sales rather than with lagged total cost”. Thereby, we deploy the Balakrishnan et al. (2014) model as below. The coefficient on β2 in Eq. (5) captures the degree of cost stickiness (BLS_OC_STICKYt). We multiply β2 by -1 so that larger value of implies a higher level of cost stickiness.

We report both the OLS and FE regression results using the Balakrishnan et al. (2014) model in Panel B of Table 8. The coefficients on BLS_OC_STICKYt are negative and significant for both TOBINQ (coefficient − 0.007, p < 0.10, column 3) and Qtot (coefficient − 0.074, p < 0.01, column 4) for the FE specification. The OLS results reported in columns (1) and (2) are also consistent with the FE regression results. By deploying the Balakrishnan et al. (2014) model we, therefore, alleviate the concern that cost stickiness captures cost structure.

We conduct additional analyses for each of the main components of operating costs, i.e., SGA and COGS, using Eq. (1). Results are reported in Table 9. Columns (1) to (4) use TOBINQ, whilst columns (5) to (8) use Qtot as the proxy for firm value. Both the OLS and FE results are reported in the table. From columns (3) and (7) we find the SGA_STICKY is related significantly and negatively to both TOBINQ (coefficient − 0.012, p < 0.01) and Qtot (coefficient − 0.010, p < 0.05). Results reported in columns (4) and (8) demonstrate that COGS_STICKY is also related significantly and negatively to both TOBINQ (coefficients − 0.036, p < 0.01) and Qtot (coefficients − 0.033, p < 0.01). Thus, we find further evidence that both SGA and COGS stickiness are negatively related to firm values.

5.2 Change analysis

In Table 10 we test whether our results are sensitive to change specification, whereby we use the changes in TOBINQ (Panel A) and Qtot (Panel B) as the dependent variables. The results from both panels show that the coefficients on ΔSTICKY continue to be negative and significant across all three STICKY (OC_STICKY, SGA_STICKY and COGS_STICKY) specifications. For example, the OLS coefficients are (− 0.020, p < 0.01; − 0.011, p < 0.01 and − 0.017, p < 0.01) and the FE coefficients are (− 0.015, p < 0.05; − 0.007, p < 0.05 and − 0.011, p < 0.10) for the regression models: results that are consistent with our main findings.

5.3 Accounting for endogeneity

Although we have provided a robust negative relationship between cost stickiness and firm value, our results may be biased owing to the presence of endogeneity concerns. These could stem from some unobservable factors driving both cost stickiness and firm value simultaneously. To mitigate potential endogeneity concerns we use the two-step system GMM (generalized method of moments) approach (Arellano & Bover, 1995; Blundell & Bond, 1998). To validate the requirement that errors in levels should be serially uncorrelated, we expect AR1 (first-order serial correlation) to be significant but expect AR2 (second-order correlation in the first-differenced residuals) to be insignificant.

Panel A of Table 11 reports the two-step system GMM results. The coefficients on OC_STICKY are negative and significant at p < 0.01 for both TOBINQ (column 1) and Qtot (column 2). It is evident that AR1 is statistically significant, and AR2 is insignificant. From column (1), the Hansen J-statistics of over-identifying restrictions implies that the instruments are valid in the two-step system GMM estimation when TOBINQ is the dependent variable.

We also use the instrumental variable (IV) based two-stage least squares (2SLS) regression estimation technique to address the endogeneity problem. We use industry mean cost stickiness (INDUS_STICKY) as an instrument, because industry and firm-level cost stickiness are highly correlated, whereas industry-level cost stickiness is unlikely to be related to firm value directly. Columns 1 and 3 of Panel B in Table 11 report the first-stage regression results, in which our endogenous variable OC_STICKY is regressed on the instrument (INDUS_STICKY) and the exogenous variables in Eq. (1). The coefficients on INDUS_STICKY are 1.06 (p < 0.01) (column 1) and 1.10 (p < 0.01) (column 3), confirming the validity of our chosen instrument. The under-identification test result (LM statistic) indicates that the excluded instrument is relevant. Based on the weak instrument test result, it is evident that the excluded instrument is correlated with our endogenous regressor, OC_STICKY. The Cragg–Donald Wald F statistic is greater than Stock and Yogo’s (2005) critical value (i.e., 16.38) at 10%, which implies that a weak instrument is not a concern. Results reported in columns 2 and 4, indicate that the coefficients on OC_STICKY are negative and significant for both TOBINQ (coefficient − 0.32, p < 0.01) and Qtot (coefficient − 0.36, p < 0.05), confirming that our results are not biased by an endogeneity concern.

6 Conclusion

In this study, we investigate the association between cost stickiness and firm value for U.S. listed companies from 1982 to 2016, and the mediating effects of the cost of equity and cash flow channels. Our overall finding is that cost stickiness is negatively relatively to firm value and is prevalent in firms with marked agency problem. Further, we find evidence that this negative association between cost stickiness and firm value is partially mediated through both the cost of equity and cash flow channels. This study not only contributes to the existing limited literature related to the implications of cost stickiness (management accounting) but also extends that literature by integrating financial accounting (firm value) and corporate finance (cost of equity and free cash flow) concepts.

Although Weiss (2010) shows that investors understand cost stickiness, the three-day CAR surrounding the earnings announcement as a proxy for market response can be noisy, as stock prices adjust slowly to new information and, hence, such a short-time window might be unable to capture the market response (Fama, 1998; Kothari, 2001). We, therefore, test for a long-term effect, and also test whether existing theories on cost stickiness help explain the negative association between cost stickiness and firm value. This study, therefore, provides insight and understanding into how managers’ deliberate resource adjustment decisions affect overall financial health and firm value. Perhaps, managers need to be more transparent about their resource adjustment decisions, so that investors can incorporate both resource adjustment costs and managerial expectations of future demand, when doing risk assessments related to their investment decisions.

Data availability

Sources of raw data are disclosed in detail in the main text of the article. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are avsailable from the corresponding author on request.

Notes

We have taken TOBINQ at period t because STICKY is the annualized mean value of the quarterly STICKY measure. Since the market updates its values based on quarterly information, we consider the end-of-year market value as an appropriate measure.

The data on the SKILL variable is retrieved from Associate Professor Frederico Belo’s webpage at https://sites.google.com/a/umn.edu/frederico-belo/.

According to this time series, the recession begins at the midpoint of the period of the peak and ends at the midpoint of the period of the trough. We define a recession dummy accordingly.

The data on DSHAR variable is retrieved from Associate Professor Elisabeth Kempf’s webpage at https://sites.google.com/site/elikempf/research?authuser=0.

GROWTH is measured as dividend yield following Henry (2008) and firms paying higher dividend yields are considered to have less growth opportunities, thus, a negative association with those firms is expected.

The untabulated OLS regression results employing two-way clustering (firm and year) are consistent with the results reported in Table 4 (coefficient − 0.049, p < 0.01 for TOBINQ and − 0.054, p < 0.01 for Qtot measure, respectively).

The untabulated OLS regression results are similar to the FE results.

As a robustness test, we have used an alternative investor sentiment measure developed by Baker and Wurgler (2006). Their sentiment proxy is based on the common variation in six underlying proxies for sentiment: the closed-end fund discount, NYSE share turnover, the number and average of first-day returns on IPOs, the equity share in new issues, and the dividend premium. As each sentiment proxy is likely to include a sentiment component as well as idiosyncratic components, the authors use principal components analysis to isolate the common component. Investor sentiment is an indicator variable coded 1 for a high sentiment period (sentiment index greater than zero) and zero otherwise. This procedure yields 1987–88, 1996–97, 1999–01, 2004 and 2006–07 as high sentiment periods. Untabulated results reveal that the coefficients on OC_STICKY are negative and significant during the low sentiment period (coefficient − 0.022, p < 0.05) and insignificant during the high sentiment period (coefficient − 0.011).

As a robustness test, we have used an alternative measure of agency cost i.e., acquisition ratio (AQC) measured as the sum of the value of all acquisitions made by a firm in a year (Compustat data item AQC), scaled by firm’s total market capitalization (Compustat data item PRCC x CSHO) (Chhaochharia et al., 2012; Giroud and Mueller, 2010). Untabulated results reveal that the coefficient on OC_STICKY is negative and significant for the high agency group (AQC > median) (coefficient − 0.022, p < 0.05) while it is insignificant for the low agency group (AQC < median).

References

Agarwal, N. (2022). Cost stickiness and stock price delay. European Accounting Review, Online Early. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2022.2121739

Anderson, M. C., Banker, R. D., & Janakiraman, S. N. (2003). Are selling, general, and administrative costs “sticky”? Journal of Accounting Research, 41(1), 47–63.

Ang, J. S., Cole, R. A., & Lin, J. W. (2000). Agency costs and ownership structure. The Journal of Finance, 55(1), 81–106.

Arellano, M., & Bover, O. (1995). Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics, 68, 29–51.

Armstrong, C. S., Core, J. E., Taylor, D. J., & Verrecchia, R. E. (2011). When does information asymmetry affect the cost of capital? Journal of Accounting Research, 49(1), 1–40.

Ashbaugh-Skaife, H., Collins, D. W., & LaFond, R. (2006). The effects of corporate governance on firms’ credit ratings. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 42, 203–243.

Bailey, G., & Szerdy, J. (1988). Is there life after downsizing? The Journal of Business Strategy, 9, 8–11.

Baker, M., & Wurgler, J. (2006). Investor sentiment and the cross-section of stock returns. The Journal of Finance, 61(4), 1645–1680.

Balakrishnan, R., Labro, E., & Soderstrom, N. S. (2014). Cost structure and sticky costs. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 26(2), 91–116.

Banker, R. D., & Byzalov, D. (2014). Asymmetric cost behavior. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 26(2), 43–79.

Banker, R. D., Byzalov, D., & Chen, L. T. (2013). Employment protection legislation, adjustment costs and cross-country differences in cost behaviour. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 55(1), 111–127.

Banker, R. D., Byzalov, D., & Plehn-Dujowich, J. M. (2014a). Demand uncertainty and cost behavior. The Accounting Review, 89(3), 839–865.

Banker, R. D., Byzalov, D., Ciftci, M., & Mashruwala, R. (2014b). The moderating effect of prior sales changes on asymmetric cost behavior. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 26(2), 221–242.

Banker, R. D., Byzalov, D., Fang, S., & Liang, Y. (2018). Cost management research. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 30(3), 187–209.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173.

Barth, M. E., Cram, D. P., & Nelson, K. K. (2001). Accruals and the prediction of future cash flows. The Accounting Review, 76(1), 27–58.

Belo, F., Li, J., Lin, X., & Zhao, X. (2017). Labor-force heterogeneity and asset prices: The importance of skilled labor. The Review of Financial Studies, 30(10), 3669–3709.

Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87, 115–143.

Botosan, C. A. (1997). Disclosure level and the cost of equity capital. The Accounting Review, 72(3), 323–349.

Calleja, K., Steliaros, M., & Thomas, D. C. (2006). A note on cost stickiness: Some international comparisons. Management Accounting Research, 17(2), 127–140.

Callen, J. L., Livnat, J., & Segal, D. (2009). The impact of earnings on the pricing of credit default swaps. The Accounting Review, 84(5), 1363–1394.

Chen, L. H., Dhaliwal, D. S., & Trombley, M. A. (2008). The effect of fundamental risk on the market pricing of accruals quality. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 23(4), 471–492.

Chen, W. P., Chung, H., Hsu, T. L., & Wu, S. (2010). External financing needs, corporate governance, and firm value. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 18, 234–249.

Chen, C. X., Lu, H., & Sougiannis, T. (2012). The agency problem, corporate governance, and the asymmetrical behavior of selling, general, and administrative costs. Contemporary Accounting Research, 29(1), 252–282.

Chen, Z., Harford, J., & Kamara, A. (2019). Operating leverage, profitability, and capital structure. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 54(1), 369–392.

Cheng, M., Dhaliwal, D. S., & Neamtiu, M. (2011). Asset securitization, securitization recourse, and information uncertainty. The Accounting Review, 86(2), 541–568.

Chhaochharia, V., Kumar, A., & Niessen-Ruenzi, A. (2012). Local investors and corporate governance. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 54, 42–67.

Cho, S. Y., Lee, C., & Pfeiffer, R. J., Jr. (2013). Corporate social responsibility performance and information asymmetry. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 32, 71–83.

Chung, K. H., & Pruitt, S. W. (1994). A simple approximation of Tobin’s q. Financial Management, 23(3), 70–74.

Ciftci, M., & Salama, F. M. (2018). Stickiness in costs and voluntary disclosures: Evidence from management earnings forecasts. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 30(3), 211–234.

Ciftci, M., Mashruwala, R., & Weiss, D. (2016). Implications of cost behavior for analysts’ earnings forecasts. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 28(1), 57–80.

Cooper, R., & Kaplan, R. S. (1992). Activity-based systems: Measuring the costs of resource usage. Accounting Horizons, 6(3), 1–13.

Costa, M. D., & Habib, A. (2023). Local creative culture and audit fees. The British Accounting Review, 55, 101151.

Costa, M. D., & Opare, S. (2022). Cost asymmetry around seasoned equity offerings. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 34, 100668.

Costa, M. D., Habib, A., & Bhuiyan, M. B. U. (2021). Financial constraints and asymmetric cost behavior. Journal of Management Control, 32, 33–83.

Dechow, P. M. (1994). Accounting earnings and cash flows as measures of firm performance: The role of accounting accruals. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 18(1), 3–42.

Dechow, P. M., Kothari, S. P., & Watts, R. L. (1998). The relation between earnings and cash flows. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 25(2), 133–168.

Drobetz, W., Grüninger, M. C., & Hirschvogl, S. (2010). Information asymmetry and the value of cash. Journal of Banking & Finance, 34, 2168–2184.

Easton, P. D. (2004). PE ratios, PEG ratios, and estimating the implied expected rate of return on equity capital. The Accounting Review, 79(1), 73–95.

El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., Kwok, C. C., & Mishra, D. R. (2011). Does corporate social responsibility affect the cost of capital? Journal of Banking & Finance, 35(9), 2388–2406.

Fama, E. F. (1998). Market efficiency, long-term returns, and behavioral finance. Journal of Financial Economics, 49(3), 283–306.

Fauver, L., & Naranjo, A. (2010). Derivative usage and firm value: The influence of agency costs and monitoring problems. Journal of Corporate Finance, 16(5), 719–735.

Finger, C. A. (1994). The ability of earnings to predict future earnings and cash flow. Journal of Accounting Research, 32(2), 210–223.

Fosu, S., Danso, A., Ahmad, W., & Coffie, W. (2016). Information asymmetry, leverage and firm value: Do crisis and growth matter? International Review of Financial Analysis, 46, 140–150.

Gao, W., & Zhu, F. (2015). Information asymmetry and capital structure around the world. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 32, 131–159.

Ghaly, M., Dang, V. A., & Stathopoulos, K. (2017). Cash holdings and labor heterogeneity: The role of skilled labor. The Review of Financial Studies, 30(10), 3636–3668.

Giroud, X., & Mueller, H. (2010). Does corporate governance matter in competitive industries? Journal of Financial Economics, 95, 312–331.

Golden, J., Mashruwala, R., & Pevzner, M. (2020). Labor adjustment costs and asymmetric cost behavior: An extension. Management Accounting Research, 46, 100647.

Gompers, P., Ishii, J., & Metrick, A. (2003). Corporate governance and equity prices. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(1), 107–156.

Grinyer, P. H., & McKiernan, P. (1990). Generating major change in stagnating companies. Strategic Management Journal, 11, 131–146.

Gupta, A., Raman, K., & Shang, C. (2018). Social capital and the cost of equity. Journal of Banking & Finance, 87, 102–117.

Habib, A., & Costa, M. D. (2022). Cost stickiness and stock price crash risk. Accounting & Finance, 62(4), 4247–4278.

Hambrick, D. C., & Schecter, S. M. (1983). Turnaround strategies for mature industrial-product business units. Academy of Management Journal, 26, 231–248.

Hartlieb, S., & Loy, T. R. (2022). The impact of cost stickiness on financial reporting: Evidence from income smoothing. Accounting & Finance, 62(3), 3913–3950.

He, J., Tian, X., Yang, H., & Zuo, L. (2020). Asymmetric cost behavior and dividend policy. Journal of Accounting Research, 58(4), 989–1021.

Henry, D. (2008). Corporate governance structure and the valuation of Australian firms: Is there value in ticking the boxes? Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 35(7–8), 912–942.

Homburg, C., Nasev, J., Reimer, K., & Uhrig-Homburg, M. (2016). Does cost management affect credit risk? SSRN: Social Science Research Network.

Hope, O. K., & Thomas, W. B. (2008). Managerial empire building and firm disclosure. Journal of Accounting Research, 46(3), 591–626.

Ibrahim, A. E. A., Ali, H., & Aboelkheir, H. (2022). Cost stickiness: A systematic literature review of 27 years of research and a future research agenda. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 46, 100439.

Jensen, M. C. (1986). Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance, and takeovers. American Economic Review, 76(2), 323–329.

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Finance Economics, 3, 305–360.

Jiao, Y. (2010). Stakeholder welfare and firm value. Journal of Banking & Finance, 34(10), 2549–2561.

Jin, Y., & Jorion, P. (2006). Firm value and hedging: Evidence from US oil and gas producers. The Journal of Finance, 61(2), 893–919.

Kaplan, S. N., & Zingales, L. (1997). Do investment-cash flow sensitivities provide useful measures of financing constraints? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(1), 169–215.

Kempf, E., Manconi, A., & Spalt, O. (2017). Distracted shareholders and corporate actions. The Review of Financial Studies, 30(5), 1660–1695.

Kim, J. B., Lee, J. J., & Park, J. C. (2019). Internal control weakness and the asymmetrical behavior of selling, general, and administrative costs. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance (forthcoming).

Konijn, S. J., Kräussl, R., & Lucas, A. (2011). Blockholder dispersion and firm value. Journal of Corporate Finance, 17(5), 1330–1339.

Kothari, S. P. (2001). Capital markets research in accounting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 31(1–3), 105–231.

Kothari, S. P., Leone, A. J., & Wasley, C. E. (2005). Performance matched discretionary accrual measures. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 39(1), 163–197.

Lemmon, M., & Portniaguina, E. (2006). Consumer confidence and asset prices: Some empirical evidence. The Review of Financial Studies, 19(4), 1499–1529.

Mansi, S. A., Maxwell, W. F., & Miller, D. P. (2011). Analyst forecast characteristics and the cost of debt. Review of Accounting Studies, 16, 116–142.

Marquardt, D. W. (1970). Generalized inverses, ridge regression, biased linear estimation, and nonlinear estimation. Technometrics, 12, 591–612.

Masulis, R. W., Wang, C., & Xie, F. (2007). Corporate governance and acquirer returns. The Journal of Finance, 62(4), 1851–1889.

Maury, B., & Pajuste, A. (2005). Multiple large shareholders and firm value. Journal of Banking & Finance, 29(7), 1813–1834.

Myers, S. C., & Majluf, N. S. (1984). Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. Journal of Financial Economics, 13, 187–221.

Nissim, D., & Penman, S. H. (2001). Ratio analysis and equity valuation: From research to practice. Review of Accounting Studies, 6(1), 109–154.

Noreen, E. (1991). Conditions under which activity-based cost systems provide relevant costs. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 3(4), 159–168.

Penman, S. (2011). Accounting for risk and return in equity valuation. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 23(2), 50–58.

Penman, S. (2016). Valuation: Accounting for risk and the expected return. Abacus, 52(1), 106–130.

Perfect, S. B., & Wiles, K. W. (1994). Alternative constructions of Tobin’s q: An empirical comparison. Journal of Empirical Finance, 1(3–4), 313–341.

Peters, R. H., & Taylor, L. A. (2017). Intangible capital and the investment-q relation. Journal of Financial Economics, 123(2), 251–272.

Plumlee, M., Brown, D., Hayes, R. M., & Marshall, R. S. (2015). Voluntary environmental disclosure quality and firm value: Further evidence. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 34(4), 336–361.

Robbins, D. K., & Pearce, J. A. (1992). Turnaround: Retrenchment and recovery. Strategic Management Journal, 13, 287–309.

Rouxelin, F., Wongsunwai, W., & Yehuda, N. (2018). Aggregate cost stickiness in GAAP financial statements and future unemployment rate. The Accounting Review, 93(3), 299–325.

Stock, J., and Yogo, M. (2005). Asymptotic distributions of instrumental variables statistics with many instruments. In Identification and inference for econometric models: Essays in honor of Thomas Rothenberg (pp. 109–120).

Studenmund, A. H. (2016). Using econometrics: A practical guide (7th ed.). Pearson.

Stulz, R. (1990). Managerial discretion and optimal financing policies. Journal of Financial Economics, 26(1), 3–27.

Varaiya, N., Kerin, R. A., & Weeks, D. (1987). The relationship between growth, profitability, and firm value. Strategic Management Journal, 8(5), 487–497.

Venieris, G., Naoum, V. C., & Vlismas, O. (2015). Organisation capital and sticky behaviour of selling, general and administrative expenses. Management Accounting Research, 26, 54–82.

Villalonga, B., & Amit, R. (2006). How do family ownership, control and management affect firm value? Journal of Financial Economics, 80(2), 385–417.

Weiss, D. (2010). Cost behavior and analysts’ earnings forecasts. The Accounting Review, 85(4), 1441–1471.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We highly appreciate the help and constructive comments from Professor Frank Verbeeten, the Managing Editor and two anonymous reviewers.

Appendix: Variable definitions

Appendix: Variable definitions

Variables | Definition of measurement |

|---|---|

Firm value variables | |

TOBINQ | Tobin’s Q, measured as Compustat data item [AT + (CSHO*PRCC_F)-CEQ-TXDB]/AT |

Qtot | Measured by scaling firm value by the sum of physical and intangible capital using Peters and Taylor (2017) methodology |

Sticky variables | |

OC_STICKY | Sticky measure of operating cost (OC) using Eq. (2) explained in Sect. 3.1. OC is calculated as Compustat data item SALEQ minus IBQ |

SGA_STICKY | Sticky measure of selling, general and administrative cost (Compustat data item XSGAQ) using Eq. (2) explained in Sect. 3.1 |

COGS_STICKY | Sticky measure of cost of goods sold (Compustat data item COGSQ) using Eq. (2) explained in Sect. 3.1 |

Control variables | |

RISK | Firm risk, calculated as the standard deviation of monthly share returns (CRSP) |

SIZE | Firm size, calculated as the natural logarithm of total assets (Compustat data item AT) |

LEV | Leverage, measured as book debt (Compustat data item DLC plus DLTT) divided by total assets (Compustat data item AT) |

PROFIT | Profit, measured as operating income before depreciation (Compustat data item OIBDP) divided by total assets (Compustat data item AT) |

GROWTH | Firm growth or investment opportunities calculated as dividend per share (Compustat data item [DVC/CSHO]) dividend by end-of year share price (Compustat data item PRCC_F) |

IOWN | Percentage of common shares held by institutional investors retrieved from Thomson Reuter’s F13 File |

Mediating variables | |

COE_PEG | Implied cost of equity, estimated by PEG model of Easton (2004) Data collected from IBES and Compustat \(PEG= \sqrt{({FEPS}_{t+2}-{FEPS}_{t+1})/{P}_{t}}\)(A.1) where, \({P}_{t}\) = the market price per share at time t (Compustat data item PRCC_F); \({FEPS}_{t+i}\) = median forecasted earnings per share (EPS) of a firm for the year i at time t |

COE_MPEG | Implied cost of equity estimated by MPEG model of Easton (2004). Data collected from IBES and Compustat \(MPEG= \sqrt{({FEPS}_{t+2}+MPEG*{DPS}_{t}-{FEPS}_{t+1})/{P}_{t}}\)(A.2) where, \(DPS\)= the current payout ratio (Compustat data item [DVPSP_F] dividend by [IBCOM/CSHO]). Following Gupta et al. (2018) we use a return on assets of 6% if the denominator is negative. We winsorize \(DPS\) to be within 0 and 1. Other variables are defined as before |

FCF | Free cash flow is measured as cash flow from operating activities less common and preferred dividends scaled by total assets (Compustat data item OANCF minus DVC minus DVP over AT) |

Control variables for COE | |

BETA | Market beta calculated from regression using monthly returns with returns of the CRSP value weighted index (including dividends) as the return on the market index using at least 36 months |

BTM | Book value to market value of equity measured as Compustat data item [CEQ/( CSHOxPRCC_F)] |

ZSCORE | Altman’s Z score calculated as 1.2(Compustat data item ACT minus LCT over AT) + 1.4 (Compustat data item RE over AT) + 3.3(Compustat data item EBIT over AT) + 0.6 (Compustat data item [CSHOxPRCC_F] over [DLTT + DLC]) + 1 (Compustat data item SALE over AT) |

DAC | The absolute value of discretionary accrual, generated from the performance-matched modified Jones model (Kothari et al., 2005). We estimate the model for all firms in the same industry with at least eight observations in an industry-year pair using the following equation: \(\frac{{ACC}_{i,t}}{{TA}_{i,t-1}}= {\delta }_{0}\left(\frac{1}{{TA}_{i,t-1}}\right)+ {\delta }_{1}\left(\frac{{\Delta SALE}_{i,t}- {\Delta REC}_{i,t}}{{TA}_{i,t-1}}\right)+ {\delta }_{2}\left(\frac{{PPE}_{i,t}}{{TA}_{i,t-1}}\right)+ {\delta }_{3}\left({ROA}_{i,t-1}\right)+{ \varepsilon }_{i,t}\) (A.3) |

where, ACC is the total accruals calculated as (Compustat data item IB minus OANCF) in year t and TA is total assets (Compustat data item AT) in year t− 1. \(\Delta SALE\) is the change in sales (Compustat data item SALE) in year t; \(\Delta REC\) is the change in accounts receivables (Compustat data item RECT) in year t; PPE is the value of property, plant and equipment (Compustat data item PPEGT) at year t; and ROA is return on assets calculated as (Compustat data item IB scaled by AT) in year t− 1. Non-discretionary accruals is the predicted value from the above equation, with DAC representing the residuals | |

Resource adjustment proxies | |

AIN | Asset intensity calculated as total assets (Compustat data item AT) divided by sales (Compustat data item SALE) |

SKILL | Belo et al., (2017, p. 3675) classify an industry to be a low-skill or high-skill industry based on the variable [SKILL], defined as the percentage of workers in that industry that work on occupations that require a high level of training and preparation, that is, are high-skill workers. The authors use two data sources i.e. (i) Dictionary of Occupational Titles and (ii) Bureau of Labor Statistics to construct the variable SKILL |

Managerial expectation proxies | |

CCI | Yearly consumer confidence index constructed by the Michigan Consumer Research Center. Higher (lower) than median value of CCI indicates consumer optimism (pessimism) |

OECD | OECD Composite Leading Indicators. According to this time series, the recession begins at the midpoint of the period of the peak and ends at the midpoint of the period of the trough. We define a recession dummy accordingly |

Agency problem proxies | |

STA | Sales-to-assets ratio, measured as sales (Compustat data item SALE) divided by total assets (Compustat data item AT). Firm-year observations with below (above)-median STA are considered high (low) agency problem groups, respectively |

DSHAR | Kempf et al.’s (2017) distracted shareholders measure. The authors first compute an investor–level distraction score, and then aggregate across all investors in the firm using the following equation (p. 1668): \({DSHAR}_{fq}= {\sum }_{{i\in F}_{q-1} }{\sum }_{{IND\ne IND}_{f}}{w}_{ifq-1}\times {w}_{iq-1}^{IND}\times {IS}_{q}^{IND}\) (A.4) where, DSHAR is distraction, Fq-1 is the set of firm f’s institutional shareholders at the end of quarter q − 1, IND is Fama–French 12 industry, and INDf is firm f’s Fama–French industry. \({IS}_{q}^{IND}\) captures whether a distracting event occurs in an industry other than INDf, and \({w}_{iq-1}^{IND}\) captures how much investor i cares about the other industry. The weight \({w}_{ifq-1}\) captures how important investor i is for firm f. Higher values of DSHAR indicatess more distracted shareholders |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Costa, M.D., Habib, A. Cost stickiness and firm value. J Manag Control 34, 235–273 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00187-023-00356-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00187-023-00356-z