Abstract

This study contributes to understanding how firms pursuing differentiation strategy enhance exploratory innovation outcomes through business partner management accountants and their use of management accounting systems. Separate streams of literature analyzed the relationship between strategy and the role of management accountants in firms; and the relationship between the role of management accountants and new product innovation. Drawing on this evidence, I hypothesize that the relationship between differentiation strategy and exploratory innovation is mediated by two factors: a greater business partner orientation of management accountants and their subsequent use of the management accounting systems for attention focusing and decision making purposes. I find empirical support for the proposed three-path mediated effect using a structural equation model with survey data from 244 firms from German-speaking countries. In total, these findings reveal that management accounting department can be part of the strategy implementation mechanism in firms that emphasize exploratory innovation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

It is well known that firms following strategies such as “prospectors” (Miles and Snow 1978) and “product differentiation” (Porter 1980) need to be successful innovators in order to sustain their competitive advantage (Chenhall et al. 2011). Exploratory product innovation is regarded as an important way in that organizations can adapt effectively to changes in markets, technology and competition (Bisbe and Otley 2004). An ongoing discussion topic, however, is the way how these firms actually manage the process from strategy formulation to innovation outcomes (Birkinshaw et al. 2008; Hofmann et al. 2012).

Existing literature suggests that management accounting and management accountants are an essential part of this management process (e.g. Hughes and Pierce 2006; Jørgensen and Messner 2010; Windeck et al. 2015). For instance, research in strategic management accounting has explored how strategy implicates the accountants’ participation in strategic decision making processes (Cadez and Guilding 2008), while another stream of research has shown how management accountants can help promote exploratory innovation (Hughes and Pierce 2006; Rabino 2001). However, the way in which management accountants and their use of management accounting information for different purposes are involved in the connection between differentiation strategy and exploratory innovation remain unclear.Footnote 1

Prior qualitative literature suggests that the roles of management accountants are moving toward a “business partner” model, generally distinguished from the more traditional “bean counter” model (Rieg 2018; Windeck et al. 2015), by taking a more active role in the decision making processes of organizations (Byrne and Pierce 2007; Hughes and Pierce 2006; Jørgensen and Messner 2010; Rabino 2001; Rieg 2018). The “bean counter” role is defined as focusing on the provision of routine financial analysis, transaction processing and/or statutory reporting (Burns and Baldvinsdottir 2005, 726; Lambert and Sponem 2012, 566). In contrast, the “business partner” role is defined as supporting top management team members in analyzing broader business management issues (Byrne and Pierce 2007, 472; Cadez and Guilding 2008, 839; Goretzki and Messner 2018; Lambert and Sponem 2012, 566; Wolf et al. 2015, 25). Literature suggests that business partnering means working closely with operational managers and developing local strategies (Byrne and Pierce 2007; Hartmann and Maas 2011), being the primary suppliers of quantifiable information for decision-support (Chang et al. 2014), and acting as a liaison device across functions and between levels of management (Cadez and Guilding 2008). As summarized by Chotiyanon and de Lautour (2018), the business partner management accountants are becoming active outside their traditional domain with topics such as helping to structure a sales promotional campaign (Ahrens 1997), designing the restaurant menu in order to meet profit targets (Ahrens and Chapman 2007), defining and evaluating profitability thresholds for the approval of new products (Jørgensen and Messner 2010), helping middle managers with budgeting (Windeck et al. 2015), or by helping in improving internal processes and working procedures (Windeck et al. 2015). Further, it has been claimed that firms with a greater business partner orientation of management accountants (BPMA) should benefit from this development (Venkatraman 2015), yet the question for which purposes do BPMAs use the information available to them has not yet been explored.

This study is designed to investigate the mediating role of BPMAs and their subsequent use of management accounting systems (MAS) in the relationship between differentiation strategy and exploratory innovation.Footnote 2 A three-path mediated effect is tested (Taylor et al. 2008). Prior research suggests that BPMAs use MAS in a rather interactive way by emphasizing communication and fact-based decision making (e.g. Bhimani and Keshtvarz 1999; Granlund and Lukka 1998). We also know that the interactive use of MAS is beneficial in the implementation of innovative strategies (Chenhall and Moers 2015; Haustein et al. 2014). This suggests that it could be expected that BPMAs will be stronger involved in the implementation of innovative strategies compared to their bean counter colleagues by using MAS in a more interactive way.

The present research is motivated by two recent developments. The first is firms’ increasing dependency on creativity and innovations (Birkinshaw et al. 2008; Cho and Pucik 2005; Dunk 2011). The second is evidence suggesting that the management accounting function in a firm can significantly impact exploratory innovation by focusing managerial attention on specific problems or by triggering action during the product innovation process (Bisbe and Malagueño 2009, 2015; Grabner 2014; Saunila et al. 2014; Ylinen and Gullkvist 2014). Thus, understanding what effects management accountants and management accounting systems have on firms’ innovation activities is becoming important, not the least because such knowledge will help firms develop more effective approaches to control by taking into account how management accountants and the different ways to use MAS can impact exploratory innovation.

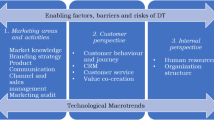

A structural equation model involving a three-path mediation is used to examine the proposed relationships (Taylor et al. 2008). As illustrated in Fig. 1, it is examined how the relationship between a differentiation strategy and firm innovation is mediated by a greater BPMA role and subsequently the four types of MAS use. The model is tested with survey data from 244 firms operating in German-speaking countries. I find support for the proposed mediating mechanism. More precisely, I find a positive relationship between differentiation strategy and the BPMA role. The BPMA role is strongly related to the use of MAS for attention focusing and decision making and, in contrast to my expectations, it is positively related to monitoring—although this latter relationship is weak. The relationship between the BPMA role and legitimization is not significant. In turn, the use of MAS for attention focusing and decision making is positively related to exploratory innovation, but the proposed negative relationship between the use of MAS for monitoring and legitimizing and innovation is not significant. In other words, this study finds that BPMA and their use of MAS sequentially mediate the relationship between differentiation strategy and exploratory innovation. This mediation is partial. In sum, the results provide insights regarding the role of management accountants and the use of management accounting systems in firms pursuing innovative strategies.

There are three potential contributions to the literature. First, this study adds to literature on the determinants of the business partner role of management accountants (Goretzki et al. 2013; Goretzki and Messner 2018; Hartmann and Maas 2011; Järvenpää 2007; Rieg 2018; Wolf et al. 2015; Zoni and Merchant 2007) by showing that differentiation strategy is an important driver of the BPMA role. This has practical consequences for firms concerned for example with the selection of the “right” management accountants during the recruitment process, or with the development of certain roles internally. Second, this study extends literature that analyses what management accountants do (e.g. Chang et al. 2014) by examining the relationship between the BPMA role and different uses of MAS. Third, this study examines the impact of management accountants on exploratory innovation through the different uses of MAS. Prior case study research observed an association between management accountants’ involvement in innovation processes and innovation outcomes (Hughes and Pierce 2006; Rabino 2001). This study contributes by identifying a mechanism through which this association is likely to work.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides the review of literature and development of the hypotheses, followed by the research method in Sect. 3. Section 4 presents the results. Section 5 closes with conclusions and limitations.

2 Literature review and development of the hypotheses

In this section relevant literature is reviewed and hypotheses are developed that lead to the conceptual model presented in Fig. 1.

2.1 Relationship between differentiation strategy and the BPMA role

Business strategy can be expected to influence the role that management accountants play in a firm (Cadez and Guilding 2008, 845) because each strategy implies different capabilities required from the organizational members (cf. Thompson and Stickland 1999, 50). Firms that emphasize strategies of product differentiation are focused on delivering high quality products or services that are perceived by their customers as superior to competition (Thompson and Stickland 1999, 49). Hence, a firm that follows a differentiation strategy might require a specific role of management accountants to support these strategic demands. Similar to Erhart et al. (2017), I assume that management accountants react to the demands of the organization and adjust their role accordingly.

In this paper I focus on two roles of management accountants commonly highlighted in literature: the “bean counter”-role and the “business partner”-role. The bean counters are considered to provide routine financial analysis, process transaction, and reporting (Burns and Baldvinsdottir 2005, 726; Lambert and Sponem 2012, 566). They are not considered to be involved in managerial decision making. Management accountants who take on the business partner role are considered to support firm managers in analyzing broader business management issues (Byrne and Pierce 2007, 472; Cadez and Guilding 2008, 839; Lambert and Sponem 2012, 566; Wolf et al. 2015, 25). The business partner contribution can range from providing strategic accounting analyses (such as customer lifetime analysis; Shank 2006) to supporting strategy implementation (Chang et al. 2014; Hartmann and Maas 2011) further to support of innovation projects (Hughes and Pierce 2006; Rabino 2001).

Literature suggest that complexity and uncertainty associated with a differentiation strategy are likely to increase the need for a greater involvement of the management accountants in day-to-day decision making (cf. Hartmann and Maas 2011, 440). It has been argued that the implementation of a differentiation strategy is more complex compared to a cost leadership strategy (cf. Anthony et al. 2014, 156–157). For instance, the business goals for firms pursuing differentiation strategy are typically more ambiguous and performance requirements tend to be not well understood (Chenhall et al. 2011, 103; Shields and Young 1994, 176). For example, the financial implications of a strategy emphasizing product quality are less likely to be understood by organizational members compared to a strategy emphasizing, let’s say, capacity utilization. The reason is that product quality does not directly lead to higher profits, but capacity utilization does.Footnote 3 Hence, operational decision making requires a greater alignment with management accounting for firms following a differentiation strategy in order to make sure that profit targets are met.

The case study by Järvenpää (2007) illustrates how a strategic shift towards a greater customer orientation implied a greater need for the involvement of management accountants into new product development, leading to the emergence of a business partner role. Lastly, survey evidence exists that differentiation-type strategies, such as product and innovation oriented strategies, are positively related to a greater accountants’ participation in strategic decision making (e.g. Cadez and Guilding 2008). On the other hand, management accountants in several firms following a differentiation strategy reported in the case study by Lambert and Sponem (2012) decided to “stick to their own work” and not to engage in business partnering. To test these ideas I propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1

A differentiation strategy is positively related to the BPMA role.

2.2 Relationship between the BPMA role and MAS use

Literature suggests that BPMAs use MAS for different purposes than the traditional types of accountants (Chang et al. 2014, 4; Hartmann and Maas 2011, 450). Henri (2006) distinguished four different purposes for which MAS could be used: strategic decision making, attention focusing, legitimization, and monitoring.Footnote 4 When used for strategic decision making, MAS is employed as a tool to evaluate business alternatives (Henri 2006). For example, a customer profitability analysis can be used to decide which customer groups should be addressed with additional products and which customers could be dropped (Kumar et al. 2008). When used for attention focusing, MAS is employed to foster organizational dialogue by sending signals throughout the organization. The purpose is to promote discussion, debate, exchange of information, and organizational learning (Argyris 1977; Henri 2006). For example, both management and floor-level employees can be provided with dashboards (e.g. balanced scorecards) containing a set of key performance indicators in order to quantify progress in several strategic areas. MAS can be used to justify decisions or actions, that is for legitimization purposes (Henri 2006). For example, a benchmark analysis that compares internal overhead costs to external best practices could be used to justify why personnel reduction programs were (or were not) started in the past. Lastly, when used for monitoring, MAS is employed to provide feedback regarding expectations and to compare outcomes to previously defined targets (Henri 2006). For example, cost reports might be provided to managers to allow them a better control of input and output relationships (van der Veeken and Wouters 2002).

Qualitative work in the management accounting literature suggests that the BPMAs are highly involved in strategic analysis and have stronger relationships with managers. For example, Burns and Baldvinsdottir (2005) find that BPMA have a greater awareness of the operational managers’ information needs for decision making. The study by Granlund and Lukka (1998) indicates that compared to bean counters, BPMAs are likely to have a wider scope of responsibility, which will probably result in a greater application of management accounting figures in business decisions. Qualitative studies by Byrne and Pierce (2007) and Granlund and Lukka (1998) find that line managers perceive BPMAs to use more management accounting information for decision making and communication. It seems that BPMAs use the information available to them to stimulate discussions and decision making based on strategic analyses. The above discussion leads to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2 a/b

The BPMA role is positively related to a) the use of MAS for strategic decision making, and b) the use of MAS for attention focusing.

Literature also suggests that BPMAs might be unwilling or unable to allocate much of their time to monitoring or legitimizing tasks that are generally perceived as a part of an “old-fashioned orientation” (Morales and Lambert 2013). Because much of their time is used to help and advise managers, to take part in daily operational decision making processes, and to undertake strategic interventions (Byrne and Pierce 2007), there simply might be not enough time left for traditional monitoring or legitimizing tasks. Furthermore, business partners might try to automate or seek to minimize tasks that they see as “dirty work” in order to give their occupation a more respectable image (Goretzki and Messner 2018; Morales and Lambert 2013). For example, the case study by Goretzki and Messner (2018) illustrates how simple reporting tasks were outsources to a shared service center in order to free up time for business partner tasks. From that follows:

Hypothesis 2 c/d

The BPMA role is negatively related to c) the use of MAS for legitimization, and d) the use of MAS for monitoring.

2.3 Relationship between the use of MAS and explorative innovation

Literature has shown a considerable interest in the relationship between management control and innovation (see reviews by Chenhall and Moers 2015 and Haustein et al. 2014). One common distinction in the innovation literature concerns the difference between explorative and exploitative innovation (March 1991). This distinction has increasingly been used in organizational (e.g. Jansen et al. 2009; Raisch et al. 2009), strategic (e.g. Uotila et al. 2009) and management control literatures (e.g. Bedford 2015; Malagueño et al. 2016). Explorative innovation is defined as a search for new knowledge that exceeds existing knowledge (Jansen et al. 2006, 2009). The aim is to develop new products and services for emerging customers and markets (March 1991). It is through explorative innovation that a firm can assure a stream of differentiated products that offer unique attributes that are valued by customers. Firms pursuing exploitative innovation, on the other hand, build on existing knowledge and seek to improve existing products and to enhance efficiency (Benner and Tushman 2003; Jansen et al. 2009; March 1991). This paper focusses on the exploratory type of innovation as the outcome of the management control process. It is theorized that the four different uses of MAS as described by Henri (2006) will have an impact on the exploratory innovation outcomes.

First, exploratory oriented firms depend on the discovery of emergent opportunities and the subsequent transformation of these opportunities into new products or services (Jansen et al. 2006). This transformation, in turn, requires a greater horizontal coordination in a firm by focusing on the overall progress of innovation initiatives across all functions (Chenhall 2009; Jansen et al. 2006). When MAS are used for attention focusing, organizational members from different functional areas are likely to be motivated to participate in discussions, debates, and exchange of information. Literature suggests that controls that build on participative communication can enhance opportunities to identify new ideas (Ylinen and Gullkvist 2014). The case study by Decoene and Bruggeman (2006) indicated that a better awareness of organizational members of the financial consequences of their actions leads to a higher intrinsic motivation, which is essential in new product development projects. Ylinen and Gullkvist (2014) found that controls that emphasize discussions are positively related to the outcomes of exploratory projects. Complementary, discussions with management accountants involving challenging the assumptions and action plans of product development teams provide an opportunity to validate new ideas and to decide whether to continue or discontinue exploratory projects (Bisbe and Malagueño 2015, 363). Such an intellectual stimulation encourages individuals to think “out of the box” and to look at problems from different angles, which is beneficial for explorative innovation (Jansen et al. 2009, 8).

Second, literature further suggests that controls that improve decision making processes can enhance motivation of individuals to look for new solutions (Ylinen and Gullkvist 2014). Searching for exploratory innovations requires breaking out organizational complacency and triggering peoples’ action to look for new ideas and opportunities. People, however, tend to cease searching for new ideas and fall into routines when they are satisfied with existing conditions (van de Ven 1986, 595). Because individuals unconsciously adapt to their environments, their thresholds for action are often not triggered while they adapt over time (van de Ven 1986, 595). The provision of MAS information for decision making is likely to disrupt complacency by stimulating discussions and debate among managers which is required for a better understanding of consequences of exploratory innovations. The study by Bedford et al. (2019) shows that MAS that are used to stimulate debate during the decision making process motivate cognitive conflict, that is questioning of existing positions, which is needed for explorative innovation. When MAS are used to make decisions, the thresholds for action are more likely to be made explicit resulting in actually triggering peoples’ action to make definitive decisions to implement or not to implement a certain explorative solution. Likewise, emphasis on enabling decisions might be expected to help control explorative projects towards launch by testing at given milestones regarding whether the explored ideas fit to key performance indicators (Bisbe and Malagueño 2015, 364). Given the discussion above, following hypotheses are formulated:

Hypothesis 3 a/b

The use of MAS for a) attention focusing and b) for strategic decision making is positively related to exploratory innovation.

Third, legitimization has been associated with mitigating risks and potential failures of unknown initiatives (Henri 2006, 85). Innovation, however, is as much about risk taking as it is about the identification of potentially promising ideas (March 1991, 71). Hence, innovative behavior requires some degree of risk tolerance and uncertainty, which seems to be incompatible with a management control environment where risk avoidance is dominant. Henri (2006) found empirically that management accounting systems use for legitimization was more likely to be found in firms with a less flexible and more centralized culture. These structures are expected to be detrimental for innovative behavior (Damanpour 1991).

Fourth, for exploratory firms, emphasis on monitoring control systems is unlikely to be beneficial (Bedford 2015; Dunk 2011). Exploratory behavior depends on experimentation and search outside existing market and technological domains. This requires activities to be loosely connected to outcomes, as learning about unfamiliar terrain is often the result of behaviors that are not goal-directed (Bedford 2015, 603). When MAS are used for monitoring, organizations develop a capacity to regulate their own behavior through a process of negative feedback, which means that goals are achieved by avoiding not achieving the goal (van de Ven 1986, 603). As a result, a space of possible actions is defined which leaves little room for innovative ideas outside these constraints. Empirically, Bedford (2015) found that explorative firms do not perform better when they use MAS in a diagnostic way. Dunk (2011) found that innovative firms benefited less from a monitoring use of budget controls. The multiple case study by Taipaleenmäki (2014) indicates that formal monitoring management accounting practices are often absent in R&D-intensive firms. These arguments suggest:

Hypothesis 3 c/d

The use of MAS c) for legitimization and d) for monitoring is negatively related to exploratory innovation.

3 Research method

3.1 Sample and data collection

The target population for this study was defined as firms or fully autonomous subunits of larger firms from German-speaking countries. Following common research conventions, companies from the industries of finance, insurance, real estate, and small firms with less than 50 employees were excluded. Using a commercial contact list, 1853 firms were selected that satisfied the selection criteria. To achieve a high response rate the following measures were taken. Chief financial officers or senior financial experts (e.g. head of controlling) of all selected firms were addressed with personalized emails and were asked to participate in the study. The 648 people who agreed to participate received another email containing a printable version of the instrument and a link to the online version of the survey (www.cfostudy.org). The number of complete questionnaires returned was 250, which results in the response rate of 13%, calculated as the number of returned questionnaires divided by the total number of people approached. During the data screening six cases were identified as outliers because the response pattern of these firms (e.g. all questions received the same item score) indicated that the respondents did not provide a true picture of their firms but simply clicked though the survey to close it. Another 23 cases had at least one missing data point. In total 0.6% of the data was missing. Because the Little’s MCAR test with expectation–maximization (EM) indicated that data was missing completely at random (Chi Square = 211,757, DF = 198, Sig. = 0.239), the missing data was replaced by the mean values.Footnote 5 After the removal of the six outliers, the final sample size is 244. Table 1 presents the characteristics of firms from different countries (panel A) and distribution across industries (panel B).

3.2 Measurement

Existing survey instruments with high reliability scales were used where possible to develop a questionnaire that was then translated to German. A back-translation procedure was applied to minimize construct validity concerns. In addition, the survey instrument was pre-tested by asking 12 respondents to complete the questionnaire and to give their feedback. This has led to some minor adjustments in the original survey design. All reflective variables were measured on a five-point scale. To check the construct reliability I apply both a Principal Component Analysis with Varimax rotation in SPSS and a Confirmatory Factor Analysis using maximum likelihood estimation in AMOS. Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 2.

3.3 Differentiation strategy

Strategy has been operationalized applying the Porter’s (1980) differentiation/cost-leadership typology and using an adopted eight items instrument from Chenhall and Langfield-Smith (1998) and Chenhall (2005). Factor analysis (Panel A of Table 2) reveals one factor with composite reliability equals to 0.85.Footnote 6

3.4 Exploratory innovation

Exploratory innovation was measured with three reflective survey items related to new product development and emphasis on research and innovations previously used by Chenhall and Morris (1995). Factor analysis (Panel A of Table 2) reveals one factor that I label INNOVATE with the composite reliability = 0.88.

3.5 MAS purpose

Purpose of MAS use as defined by Henri (2006) is a multidimensional construct with four sub-dimensions. In order to operationalize the four different purposes for which MAS can be used, the respondents were first shown a list of 15 most known management accounting systems derived from Cadez and Guilding (2008) (e.g. budgets, non-financial measures, ABC, BSC, and others). Then respondents were asked how often the previously shown MAS were used for the four purposes of strategic decision making, attention focusing, legitimization, and monitoring applying the 14 reflective items from Henri (2006) that have been used by other researchers as well (Guenther and Heinicke 2018).Footnote 7 Factor analysis (Panel A of Table 2) reveals four factors with eigenvalues greater than one that I label DECIDE, ATTENT, LEGITIM, and MONITOR. The composite reliability for these factors range from 0.79 to 0.87.

3.6 BPMA role

I calculate a formative index to measure the degree to which management accountants take on the BPMA role. The index is build based on the relative amount of time that management accountants allocate on average to specific tasks during a calendar year. The time allocation is measured with six categories derived from the finance-framework by the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW 2011). Measuring the activities of the management accountants to assess their role in an organization is in line with suggestions by (Mahlendorf 2014, 35). The respondents were asked to allocate exactly 100 points to the following answer categories: (1) Time spend on accounting and reporting; (2) Time spend on risk management and compliance; (3) Time spend on funding; (4) Time spend on management accounting and control; (5) Time spend on strategic analysis; (6) Time spend on other activities. The definition of BPMA implies that business partner should be stronger involved in management accounting and control, strategic analysis and other activities such as ERP projects (see exact survey items in attachment). Bean counters, on the other hand, should be stronger involved in accounting and reporting, risk management and compliance, and funding.

Hence, as both management accounting roles are considered to be two opposite ends of a continuum describing management accountants’ time allocation, I expect to observe two groups of management accountants with one group focusing on the business partner tasks and the other group focusing on the bean counter tasks. I perform a cluster analysis to empirically assess this expectation. Cluster analysis uses several input parameters to identify homogenous mutually exclusive groupings within a population (Ketchen and Shook 1996). I employ a two stage clustering process in SPSS. This process first runs a pre-clustering to build a number of pre-clusters based on the distance criterion and then in the second step merges the pre-clusters until the desired number of clusters is reached (Ketchen and Shook 1996). Because the descriptive analysis of the data showed a close to normal distribution of data (not tabulated), the log-likelihood estimator with Bayesian Information Criterion is used to calculate the distance between clusters. In line with my theoretical considerations regarding the roles of management accountants, I define two clusters in the procedure. The results of the cluster analysis are shown in Panel B of Table 2. I label the clusters based on the interpretation of mean time distribution between the different activities: bean counters spend relatively more time on accounting and reporting, risk management, compliance, and funding, while business partners spend relatively more time on management accounting and control, strategic analysis, and other activities.

Given the results of the cluster analysis, I compute a formative index BUSINESS representing the degree to which the management accountants take on the BPMA role by adding the scores of the items related to the business partner cluster and subtracting the items relating to the bean counter cluster.

3.7 Control variables

I control for the effects of several contingency variables on both exploratory innovation and business partner role of management accountants. First, firm size could have an effect on both of these variables. For example, large firms with slack resources might be more easily engaged in innovation (Damanpour 1991), while management accountants could be more often concerned with strategy issues in larger firms compared to smaller firms (Chang et al. 2014). SIZE is calculated as a formative index by averaging of logarithmized firms’ revenue and number of employees.

Second, firms that engage in price competition tend to emphasize low cost production and save on product quality (cf. Porter 1980) which could have a negative effect on exploratory innovation. In addition, the resources in low cost firms are likely to be scarcely distributed to the overhead functions, so there could be no capacity left for strategic tasks in the management accounting department. I use two reflective items from Chenhall and Langfield-Smith (1998) and Chenhall (2005) to measure the degree to which a firm follows a cost leadership strategy COST (CR = 0.90, Panel A of Table 2).

Third, organizational centralization has been argued to negatively affect exploratory innovation, as it represents the concentration of decision making authority (Damanpour 1991, 558; Jansen et al. 2006, 1663). The concentration of decision making authority prevents innovative solutions; the dispersion of power is necessary for innovation (Damanpour 1991, 558). Similarly, centralized firms are more likely to use formal procedures and closely monitor financial targets, which would have an impact on the role of management accountants (Chang et al. 2014). Four reflective items from previous literature were borrowed to measure centralization CENTR (Deshpande and Zaltman 1982; Hage and Aiken 1967). The composite reliability of this factor is 0.88 (Panel A of Table 2).

Fourth, the life-cycle stage of a firm can have a pronounced impact on innovation (Holthausen et al. 1995, 284). At an early point in the firm’s life-cycle (where a standardized product has not evolved), there are substantial potential rents to innovation activities. In contrast, once a firm’s product is mature (where the market exhibits an accepted standardized product), there are much lower economic rents to exploratory innovation (Miller and Friesen 1984). This would suggest a negative relation between the maturity life-cycle stage and innovation. A variable MATURE is set to one if firms self-categorized themselves as being located at the maturity life-cycle stage using the instrument from Kallunki and Silvola (2008), and zero otherwise.

Fifth, industry may also be important as it can capture the potential effects of different types of production technologies, which may in turn influence the role of management accountants and the emphasis on innovations. Similar to Chenhall et al. (2011), firms were grouped in manufacturing and non-manufacturing groups as these groups typically face different types of production complexities, management control approaches, and the need to innovate (Chenhall et al. 2011). 44% of the firms in the sample are from manufacturing industry. A dummy variable MFTG was set to one if the firm’s main competitive market was in manufacturing (SIC numbers 20–39), and zero otherwise.

Sixth, I measure the number of finance and accounting personnel in a firm with a formative survey item FINFTE. Similar to firm size, I expect the number of people working in the finance department to be related to the available capacity that could be allocated to more strategic tasks, and hence to the role of the management accountants. I covary FINFTE and SIZE in the structural equation model (cf. Byrne 2005, 22).

Seventh, I control for the covariance between the four purposes of MAS use (cf. Byrne 2005, 22) because I assume that the four uses are related (see correlation table).

Lastly, as I theorize a mediating mechanism between strategy and innovation, the direct relationship between strategy (DIFF) and innovation (INNOVATE) is added to the model in order to test the three-path mediated effect (James et al. 2006; Taylor et al. 2008).

4 Results

4.1 Data normality and estimation method

A review of univariate skewness and kurtosis shows that some items exhibit nonnormality (skewness above 3; see Curran et al. 1996; Hampton 2015; Kline 1998). Hence, multivariate nonnormality is problematic. To mitigate this problem maximum likelihood estimation method in AMOS with 5000 bootstrapping samples was used (Hampton 2015; Nevitt and Hancock 2001).

4.2 Full latent model

James and Brett (1984) recommended that if theoretical mediation models are thought of as causal models, then strategies designed specifically to test the fit of causal models to data, such as structural equation modeling (SEM), should be employed to test mediation. In line with this suggestion, I empirically test a model involving a three-path mediation using SEM (James et al. 2006; Taylor et al. 2008). The three-path mediated effect is tested applying the joint significance test as described by Taylor et al. (2008).

The full latent model based on the conceptual model depicted in Fig. 1 was estimated. The full latent model consists of both, the measurement and the structural models. The measurement model is concerned with the measurement properties of the instruments (reliability, validity, and common measure bias for the reflective constructs), while the structural model is concerned with causal relationships among the constructs and their relative explanatory power (Byrne 2013, 6–12; Schreiber et al. 2006, 325; Smith and Langfield-Smith 2004, 54).

4.3 Measurement model

The measurement model is built based on existing scales from prior empirical literature. Consequently, the relations between the observed measures and the underlying factors were proposed a priori and then tested using the Confirmatory Factor Analysis in AMOS (Byrne 2005, 17). As latent variables are not directly measured and thus have no definite metric scale, each of them was assigned a scale by setting the loading of one item for each latent construct to 1.0 (Byrne 2006, 32).

To assess convergent validity the individual item loadings, the composite reliability (CR), and the average variance extracted (AVE) are evaluated (Hampton 2015; Mackenzie et al. 2011). Discriminant validity is assessed through the examination of indicator cross-loadings, construct correlations, and the degree to which a construct explains its indicators better than it explains other constructs (Hampton 2015; Mackenzie et al. 2011). As shown in Table 2, all items reach standardized loadings equal to or greater 0.67, suggesting that the constructs explain a substantial portion of the indicator variance. Item cross-loading are checked by the examination of an eight-factor solution from the principal component analysis with varimax rotation. No surprisingly high cross-loadings are revealed (all below 0.4, not tabulated). Table 3 shows that the squared root of AVE of all constructs is higher than the bivariate correlations of the related constructs (Fornell and Larcker 1981). The composite reliability (CR) of all constructs exceeds 0.79, indicating that indicators consistently represent the construct. Moreover, the average variance extracted (AVE) of all constructs reaches the threshold value of 0.53 which indicates that at least 50% of the indicator variance is accounted for by construct variance rather than noise (Hampton 2015; Mackenzie et al. 2011). Based on these results, I conclude that the measurement model has sufficient convergent and discriminant validity. That means that the items that should measure a specific construct actually measure this construct and the different constructs represent distinctive phenomena.

Because the variables are constructed from one survey, common method bias is assessed next. A priori, it was attempted to reduce the potential effects of common method variance by presenting the items in the online questionnaire on separate pages and by selecting different scales for some of the variables. In addition, respondent anonymity was assured to reduce possible evaluation apprehension (Podsakoff et al. 2003, 888). A posteriori, common method variance is assessed applying the Harman’s one-factor test (Podsakoff et al. 2003). To this purpose, all items are loaded on one factor to see whether a potential common method factor appears in the data. The unrotated one-factor solution explains 22.5% of the variance. Further, principal component analysis with varimax rotation reveals eight factors rather than one, and the first factor explains 13.3% of the total variance. Thus, neither a single factor appears nor does one factor account for a large portion of the variance in the data, which shows that the likelihood of common measure bias is very low (Podsakoff et al. 2003, 889).

4.4 Structural model

The fit of the structural model is evaluated next using the Chi square divided by the degrees of freedom (CMINDF), the comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis fit index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) as indicators of fit. A CMINDF ratio < 3.0 (Schreiber et al. 2006), a CFI and TLI close to 0.95 (Hu and Bentler 1999; Schreiber et al. 2006), and an RMSEA of < 0.06 (Hu and Bentler 1999; Schreiber et al. 2006) indicate good fit. As shown in Table 5, all fit indices of the base model reach the required thresholds (CFI = 0.951; TLI = 0.944; CMINDF = 1.364; RMSEA = 0.039) which means that the model is well fitting the data.

4.5 Hypothesis testing

Next, the proposed hypotheses are tested by assessing the individual parameter estimates. First of all, there is a direct and positive relationship between the extent to which a firm follows a differentiation strategy and exploratory innovation (0.201, p < 0.01). Hence, there exists a relationship which can be mediated (James et al. 2006; Preacher and Hayes 2004). Second, consistent with H1 (0.224, p < 0.01), a differentiation strategy is positively related to the BPMA role. Third, the associations between the PBMA role and use of MAS for decision making (0.354, p < 0.01) and attention focusing (0.316, p < 0.01) are positive and significant. H2a and H2b are hence supported. The relationship between the BPMA role and the use of MAS for legitimization has the opposite of the expected sign and is not significant (0.123, p > 0.10). Lastly, the relationship between the BPMA role and monitoring use of MAS has the opposite sign as well and it is significant (0.151, p < 0.10). H2c/d are thus not supported.

Finally, there are positive and significant relationships between attention focusing and decision making use of MAS and innovation (0.255, p < 0.05 and 0.255 < 0.01, resp.), supporting H3a/b. The relationships between legitimization/monitoring and innovation proposed in H3c/d are not significant (− 0.014, p > 0.10 and 0.004, p > 0.10, resp.). These relationships are presented in Fig. 3. In total, the results indicate the existence of a three-path mediation mechanism of the BPMA role and the use of MAS between strategy and exploratory innovation, which is formally tested next.

4.6 Test of the three-path mediated effect

According to Taylor et al. (2008), one way to test the three-path mediated effect is to show that all regression coefficients making up the mediated effect were significantly nonzero and that the effects were in the predicted direction. To determine whether the mediation is complete or partial it is required to test the direct path between the independent and the outcome variables with and without the presence of the indirect paths (James et al. 2006, 242). If the direct path alone is significant and the significance is reduced to zero in the presence of the indirect paths, then the mediation is complete. If the significance of the direct path is not reduced to zero in the presence of the indirect paths, then the mediation is partial (James et al. 2006).

Hence, in order to establish a three-path mediated effect it is required to show that the direct relationship between the independent variable (differentiation strategy) and the outcome variable (innovation) is significant; and that the regression coefficients of the paths through the two mediators (BPMA role, use of MAS) are jointly significant as well (James et al. 2006; Preacher and Hayes 2004). The direct path a between the independent and the outcome variables is shown in panel A of Fig. 2. The direct path between the independent and the outcome variables controlling to the indirect paths is labeled a′ in panel B of Fig. 2. The four indirect paths through the mediating variables in panel B are β1β2β3, β1β4β5, β1β6β7, β1β8β9.

I use a series of structural equation models to test each (direct and indirect) path from strategy to innovation in isolation. The results are presented in Table 4. The direct path a is positive and significant (0.310; p < 0.01). Further, for all indirect paths β1β2β3, β1β4β5, β1β6β7, β1β8β9 all three coefficients are jointly significant. In contrast to my expectations, the regression coefficients for the paths between BPMA role and monitoring (β2) and legitimization (β4) and the subsequent paths to innovation (β3; β5) are positive. In line with my expectations, the regression confidents between BPMA role and attention focusing (β6) and decision making (β8) and the subsequent paths to innovation (β7; β9) are positive. The significance of all three coefficients per path means that the joint significance test rejected the null hypothesis of no mediation (Taylor et al. 2008). In sum, given the opposite signs for the paths through monitoring/legitimization, only the predicted indirect paths from differentiation strategy to exploratory innovation through the sequential mediators BPMA role and attention focusing/decision making are supported (Fig. 3).

Lastly, the significance of the direct path a′ is lower in the presence of the indirect paths but it is not zero (0.195; p < 0.05). Thus, the mediation is partial (James et al. 2006).

4.7 Alternative specifications

Although the base model presented in Table 5 is well fitting, there is no assurance that it is the only model. The purpose of this section is to compare the base model to alternative models (nested models) and to assess the robustness of results to alternative model specifications. Two nested models can be compared using a χ2 difference test.Footnote 8 A significant test result indicates that the more complex model (i.e. the one with less degrees of freedom) is better fitting the data than the less complex model (i.e. the one with more degrees of freedom) (Kline 1998). If the test is insignificant, then both models fit equally well statistically, so the parameters in question can be eliminated from the model (fixed to zero) and the simpler model (i.e. the one with more degrees of freedom) should be accepted (Schermelleh-Engel et al. 2003).

Table 6 reports the results of four additional models named model 2 to model 5. These nested models are built from the base model by adding paths between variables. In model 2, an additional path from the BUSINESS to INNOVATE is added in order to capture other effects of management accountants on innovation, above the theorized use of MAS. The insignificant χ2 difference test shows that this model is not better than the base model (cf. Schermelleh-Engel et al. 2003). In model 3, direct paths from DIFF to the different uses of MAS are added, as it is known that strategy is related to the use of MAS (e.g. Cadez and Guilding 2008; Cinquini and Tenucci 2010; Cuganesan et al. 2012; Ittner and Larcker 1997). The proposed paths are significant, model fit indices (RMSEA, TLI, CFI) are equally good, and the χ2 difference test is significant. Hence, this model fits the data equally good. In model 4, additional paths from COST to the different uses of MAS are added. This model does not outperform the base model. Finally, in model 5 both DIFF and COST are directly linked to the different uses of MAS. Similar to model 3, model 5 outperforms the base model.

In total, all alternative specifications except the models 3 and 5 with additional paths between differentiation strategy and the uses of MAS are rejected. These models were not hypothesized a priori, but emerged from the data analysis.

Lastly, a model was tested that included additional control paths between context variables and MAS use. The main results remained unchanged, except that the relationship between BPMA and the monitoring use of MAS did not reach significance.

5 Conclusions and discussion

The purpose of this study was to test a three-path mediation mechanism between differentiation strategy and exploratory innovation involving the business partner role of management accountants (BPMA role) and four different uses of management accounting systems (MAS) as subsequent mediators. The results of a structural equation model indicate that the relationship between differentiation strategy and exploratory innovation is mediated by the sequential mediators BPMA role and use of MAS for decision making and attention focusing purposes. The mediation is partial. This finding is consistent with management accounting literature arguing that increased innovation and less routine tasks require a greater involvement of management accountants in managerial decision making (Chapman 1997), because the BPMA role implies a greater management support on a broader set of issues.

In total, this study suggests that management accountants in firms following a differentiation strategy take a more proactive role as business partners by emphasizing a greater use of MAS for attention focusing and decision making. In turn, the use of MAS for attention focusing and decision making was found to positively impact exploratory innovation. There was no impact from monitoring and legitimization use. These findings fit to prior results in literature that firms that emphasize exploratory innovation benefit from the interactive use of MAS (Bedford 2015). Another interesting finding is that the diagnostic use of MAS had no detrimental effect of exploratory innovation (Bedford 2015).

As in all studies there are limitations. First of all, this study sets a narrow focus and investigates only few factors that potentially affect exploratory innovation: the role of management accountants and MAS use. Second, this study relies on survey data from firms in German-speaking countries. Despite measures that were taken to ensure instrument reliability (e.g. pre-test of instrument) and satisfactory post hoc diagnostics (e.g. reliability, validity, common method bias), indicators may be noisy and caution should be taken when generalizing the results to other populations and other countries. Third, this study relies on cross-sectional data which does not allow a direct test of causality. Future studies building time into the design could be conducted in order to provide a better assessment of causality. Fourth, different instruments exist for operationalization of the variables analyzed in this study and it is not clear how the results would have changed if other items were used. For example, a parallel set of papers uses different instruments measuring exploration/exploitation (Jansen et al. 2006, 1663; Ylinen and Gullkvist 2014). It is not clear how the alternative construct measurement would have affected the results.

Future studies could build upon the results of this work and analyze some of the relationships that were not covered in this study. For example, the role of BPMAs in firms following the cost leadership strategy is not discussed. Rather, cost leadership is used as a control variable. It could be, however, that firms emphasizing efficient production and low cost will assign less resources to strategic analyses (cf. Bendoly et al. 2009) and prefer to have a rather traditional type of management accountants mainly focusing on reporting and monitoring tasks. The benefit of BPMAs in low cost firms might then be altered and the value of the “bean counters” could increase in such firms. Assuming that process efficiency and exploitative innovation would be more suitable performance indicators for firms following a cost leadership strategy, future studies could contrast the different types of management accountants in firms following different strategies in the relationship to exploitation and exploration.

Similar issues concern the observed negative relationship between centralization and BPMA. It suggests that organizational demand for decentralized local decision making generates a need for greater business partner support from management accountants. While this finding complements evidence from Chang et al. (2014) who found that decentralization is negatively related to the traditional fiduciary tasks of accountants, future studies could build upon these results and investigate, for example, performance outcomes of the fit between organizational structure and the role of management accountants.

Notes

According to Hughes and Pierce (2006), some potential areas of contribution by management accountants are as follows: (1) a business partner accountant may introduce new and innovative management control systems, such as Balanced Scorecard; (2) a business partner accountant may introduce total quality management into the NPD process and tailor risk and uncertainty management to the needs of the NPD team; (3) finally, there is also scope to make a better contribution to measurement of functionality and product attributes.

Exploratory innovation is defined as a search for new knowledge that exceeds existing knowledge (Jansen et al. 2006; Jansen et al. 2009). The aim is to develop new products and services for emerging customers and markets (March 1991). It is through exploratory innovation that a firm can assure a stream of differentiated products that offer unique attributes that are valued by customers.

One idea often found in marketing literature is that product quality will eventually transform into economic value (e.g. Anderson et al. 2004; Gruca and Rego 2005). However, Doyle (2000, 299) points out that this belief is misleading because increasing service quality can always increase sales, market share and customer satisfaction, but not necessary profitability margins.

Note that the use of MAS for decision making and attention focusing is considered in literature to represent an interactive approach to control, while the use for legitimization and monitoring is considered to be diagnostic (Guenther and Heinicke 2018; de Harlez and Malagueño 2016; Bedford et al. 2016).

Main results do not change if the 23 cases with mean replaced missing values are excluded from the analysis (not tabulated).

13 out of 27 items originally used by Henri (2006) were dropped during the instrument test phase (one item related to monitoring, three items related to attention focusing, four items related to decision making, and five items related to legitimization) because they were considered strongly overlapping or ambiguous by test respondents.

For the χ2 difference test to be valid, at least the less restrictive model should fit the data, i.e. the test is meaningless if one of the models does not fit the data well (Schermelleh-Engel et al. 2003). If one model does not fit the data well, another parameters could be used to compare the models, such as the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), with a lower AIC score indicating a better model (Schermelleh-Engel et al. 2003).

References

Ahrens, T. (1997). Strategic interventions of management accountants: Everyday practice of british and german brewers. European Accounting Review, 6(4), 557–588.

Ahrens, T., & Chapman, C. S. (2007). Management accounting as practice. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 32(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2006.09.013.

Anderson, E. W., Fornell, C., & Mazvancheryl, S. K. (2004). Customer satisfaction and shareholder value. Journal of Marketing, 68(4), 172–185.

Anthony, R. N., Govindarajan, V., Hartmann, F. G. H., Krause, K., & Nilsson, G. (2014). Management control systems. London: McGrawHill Education Higher Education.

Argyris, C. (1977). Organizational learning and management information systems. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 2(2), 113–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(77)90028-9.

Bedford, D. S. (2015). Management control systems across different modes of innovation: Implications for firm performance. Management Accounting Research, 28, 12–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2015.04.003.

Bedford, D. S., Bisbe, J., & Sweeney, B. (2019). Performance measurement systems as generators of cognitive conflict in ambidextrous firms. Accounting, Organizations and Society. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2018.05.010.

Bedford, D. S., Malmi, T., & Sandelin, M. (2016). Management control effectiveness and strategy: An empirical analysis of packages and systems. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 51, 12–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2016.04.002.

Bendoly, E., Rosenzweig, E. D., & Stratman, J. K. (2009). The efficient use of enterprise information for strategic advantage: A data envelopment analysis. Journal of Operations Management, 27(4), 310–323.

Benner, M. J., & Tushman, M. L. (2003). Exploitation, exploration, and process management: The productivity dilemma revisited. The Academy of Management Review, 28(2), 238–256.

Bhimani, A., & Keshtvarz, M. H. (1999). British management accountants. Journal of Cost Management, 13(2), 25–31.

Birkinshaw, J., Hamel, G., & Mol, M. J. (2008). Management innovation. The Academy of Management Review, 33(4), 825–845.

Bisbe, J., & Malagueño, R. (2009). The choice of interactive control systems under different innovation management modes. European Accounting Review, 18(2), 371–405.

Bisbe, J., & Malagueño, R. (2015). How control systems influence product innovation processes: Examining the role of entrepreneurial orientation. Accounting and Business Research, 45(3), 356–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2015.1009870.

Bisbe, J., & Otley, D. (2004). The effects of the interactive use of management control systems on product innovation. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29(8), 709–737.

Burns, J., & Baldvinsdottir, G. (2005). An institutional perspective of accountants’ new roles: The interplay of contradictions and praxis. European Accounting Review, 14(4), 725–757. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180500194171.

Byrne, B. M. (2005). Factor analytic models: Viewing the structure of an assessment instrument from three perspectives. Journal of Personality Assessment, 85(1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa8501_02.

Byrne, B. M. (2006). Structural equation modeling with eqs: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Byrne, B. M. (2013). Structural equation modeling with amos: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis.

Byrne, S., & Pierce, B. (2007). Towards a more comprehensive understanding of the roles of management accountants. European Accounting Review, 16(3), 469–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180701507114.

Cadez, S., & Guilding, C. (2008). An exploratory investigation of an integrated contingency model of strategic management accounting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(7/8), 836–863.

Chang, H., Ittner, C. D., & Paz, M. T. (2014). The multiple roles of the finance organization: Determinants, effectiveness, and the moderating influence of information system integration. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 26(2), 1–32.

Chapman, C. S. (1997). Reflections on a contingent view of accounting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 22(2), 189–205.

Chenhall, R. H. (2005). Integrative strategic performance measurement systems, strategic alignment of manufacturing, learning and strategic outcomes: An exploratory study. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 30(5), 395–422.

Chenhall, R. H. (2009). Accounting for the horizontal organization. In C. S. Chapman, A. G. Hopwood, & M. D. Shields (Eds.), Handbook of management accounting research (pp. 1207–1233). Oxford: Elsevier.

Chenhall, R. H., Kallunki, J.-P., & Silvola, H. (2011). Exploring the relationships between strategy, innovation, and management control systems: The roles of social networking, organic innovative culture, and formal controls. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 23(1), 99–128.

Chenhall, R. H., & Langfield-Smith, K. (1998). The relationship between strategic priorities, management techniques and management accounting: An empirical investigation using a systems approach. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 23(3), 243–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-3682(97)00024-X.

Chenhall, R. H., & Moers, F. (2015). The role of innovation in the evolution of management accounting and its integration into management control. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 47, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2015.10.002.

Chenhall, R. H., & Morris, D. (1995). Organic decision and communication processes and management accounting systems in entrepreneurial and conservative business organizations. Omega, 23(5), 485–497.

Cho, H.-J., & Pucik, V. (2005). Relationship between innovativeness, quality, growth, profitability, and market value. Strategic Management Journal, 26(6), 555–575. https://doi.org/10.2307/20142249.

Chotiyanon, P., & de Lautour, V. J. (2018). The changing role of the management accountants: Becoming a business partner. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cinquini, L., & Tenucci, A. (2010). Strategic management accounting and business strategy: A loose coupling? Journal of Accounting and Organizational Change, 6(2), 228–259. https://doi.org/10.1108/18325911011048772.

Cuganesan, S., Dunford, R., & Palmer, I. (2012). Strategic management accounting and strategy practices within a public sector agency. Management Accounting Research, 23(4), 245–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2012.09.001.

Curran, P. J., West, S. G., & Finch, J. F. (1996). The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 1(1), 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.16.

Damanpour, F. (1991). Organizational innovation: A meta-analysis of effects of determinants and moderators. The Academy of Management Journal, 34(3), 555–590.

de Harlez, Y., & Malagueño, R. (2016). Examining the joint effects of strategic priorities, use of management control systems, and personal background on hospital performance. Management Accounting Research, 30(March), 2–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2015.07.001.

Decoene, V., & Bruggeman, W. (2006). Strategic alignment and middle-level managers’ motivation in a balanced scorecard setting. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 26(4), 429–448. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570610650576.

Deshpande, R., & Zaltman, G. (1982). Factors affecting the use of market research information: A path analysis. Journal of Marketing Research, 19(1), 14–31.

Doyle, P. (2000). Value-based marketing. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 8(4), 299–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/096525400446203.

Dunk, A. S. (2011). Product innovation, budgetary control, and the financial performance of firms. British Accounting Review, 43(2), 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2011.02.004.

Erhart, R., Mahlendorf, M. D., Reimer, M., & Schäffer, U. (2017). Theorizing and testing bidirectional effects: The relationship between strategy formation and involvement of controllers. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 61, 36–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2017.07.004.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Goretzki, L., & Messner, M. (2018). Backstage and frontstage interactions in management accountants’ identity work. Accounting, Organizations and Society. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2018.09.001.

Goretzki, L., Strauss, E., & Weber, J. (2013). An institutional perspective on the changes in management accountants’ professional role. Management Accounting Research, 24(1), 41–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2012.11.002.

Grabner, I. (2014). Incentive system design in creativity-dependent firms. The Accounting Review, 89(5), 1729–1750. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-50756.

Granlund, M., & Lukka, K. (1998). Towards increasing business orientation: Finnish management accountants in a changing cultural context. Management Accounting Research, 9(2), 185–211. https://doi.org/10.1006/mare.1998.0076.

Gruca, T. S., & Rego, L. L. (2005). Customer satisfaction, cash flow, and shareholder value. Journal of Marketing, 69(3), 115–130.

Guenther, T. W., & Heinicke, A. (2018). Relationships among types of use, levels of sophistication, and organizational outcomes of performance measurement systems: The crucial role of design choices. Management Accounting Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2018.07.002.

Hage, J., & Aiken, M. (1967). Relationship of centralization to other structural properties. Administrative Science Quarterly, 12(1), 72–92.

Hampton, C. (2015). Estimating and reporting structural equation models with behavioral accounting data. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 27(2), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.2308/bria-51226.

Hartmann, F. G. H., & Maas, V. S. (2011). The effects of uncertainty on the roles of controllers and budgets: An exploratory study. Accounting and Business Research, 41(5), 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2011.597656.

Haustein, E., Luther, R., & Schuster, P. (2014). Management control systems in innovation companies: A literature based framework. Journal of Management Control, 24(4), 343–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00187-014-0187-5.

Henri, J.-F. (2006). Organizational culture and performance measurement systems. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 31(1), 77–103.

Hofmann, S., Wald, A., & Gleich, R. (2012). Determinants and effects of the diagnostic and interactive use of control systems: An empirical analysis on the use of budgets. Journal of Management Control, 23(3), 153–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00187-012-0156-9.

Holthausen, R. W., Larcker, D. F., & Sloan, R. G. (1995). Business unit innovation and the structure of executive compensation: Organizations, incentives, and innovation. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 19(2–3), 279–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-4101(94)00385-I.

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Hughes, P., & Pierce, B. (2006). The accountant’s contribution to new product development. Irish Accounting Review, 13(1), 47–68.

ICAEW. (2011). The finance function: a framework for analysis. Finance direction initiative. Available online at http://www.icaew.com/~/media/corporate/files/technical/business%20and%20financial%20management/finance%20direction/finance%20function%20a%20framework%20for%20analysis.ashx. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

Ittner, C. D., & Larcker, D. F. (1997). Quality strategy, strategic control systems, and organizational performance. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 22(3–4), 293–314.

James, L. R., & Brett, J. M. (1984). Mediators, moderators, and tests for mediation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69(2), 307–321.

James, L., Mulaik, S., & Brett, J. (2006). A tale of two methods. Organizational Research Methods, 9(2), 233–244.

Jansen, J. J. P., Van Den Bosch, F. A. J., & Volberda, H. W. (2006). Exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation, and performance: Effects of organizational antecedents and environmental moderators. Management Science, 52(11), 1661–1674. https://doi.org/10.2307/20110640.

Jansen, J. J. P., Vera, D., & Crossan, M. (2009). Strategic leadership for exploration and exploitation: The moderating role of environmental dynamism. Leadership and Organizational Learning, 20(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.11.008.

Järvenpää, M. (2007). Making business partners: A case study on how management accounting culture was changed. European Accounting Review, 16(1), 99–142.

Jørgensen, B., & Messner, M. (2010). Accounting and strategising: A case study from new product development. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 35(2), 184–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2009.04.001.

Kallunki, J.-P., & Silvola, H. (2008). The effect of organizational life cycle stage on the use of activity-based costing. Management Accounting Research, 19(1), 62–79.

Ketchen, D. J., & Shook, C. L. (1996). The application of cluster analysis in strategic management research: An analysis and critique. Strategic Management Journal, 17(6), 441–458.

Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press.

Kumar, V., Venkatesan, R., Bohling, T., & Beckmann, D. (2008). The power of clv: Managing customer lifetime value at ibm. Marketing Science, 27(4), 585–599. https://doi.org/10.2307/40057110.

Lambert, C., & Sponem, S. (2012). Roles, authority and involvement of the management accounting function: A multiple case-study perspective. European Accounting Review, 21(3), 565–589.

Mackenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, P. M., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2011). Construct measurement and validation procedures in mis and behavioral research: Integrating new and existing techniques. MIS Quarterly, 35(2), 293.

Mahlendorf, M. D. (2014). Discussion of the multiple roles of the finance organization: Determinants, effectiveness, and the moderating influence of information system integration. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 26(2), 33–42.

Malagueño, R., Lopez-Valeiras, E., & Gomez-Conde, J. (2016). Examining the impact of planning and control sophistication on innovation orientations. In Proceedings of the EAA 39th annual conference.

March, J. G. (1991). Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2(1), 71–87.

Miles, R., & Snow, C. C. (1978). Organisational strategy, structure and process. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Miller, D., & Friesen, P. H. (1984). A longitudinal study of the corporate life cycle. Management Science, 30(10), 1161–1183.

Morales, J., & Lambert, C. (2013). Dirty work and the construction of identity: An ethnographic study of management accounting practices. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 38(3), 228–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2013.04.001.

Nevitt, J., & Hancock, G. R. (2001). Performance of bootstrapping approaches to model test statistics and parameter standard error estimation in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 8(3), 353–377. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0803_2.

Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879.

Porter, M. (1980). Competitive strategy: Techniques for analysing industries and competitors. New York: The Free Press.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(4), 717–731. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03206553.

Rabino, S. (2001). The accountant’s contribution to product development teams: A case study. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 18(1), 73–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0923-4748(00)00034-5.

Raisch, S., Birkinshaw, J., Probst, G., & Tushman, M. L. (2009). Organizational ambidexterity: Balancing exploitation and exploration for sustained performance. Organization Science, 20(4), 685–695.

Rieg, R. (2018). Tasks, interaction and role perception of management accountants: Evidence from Germany. Journal of Management Control, 29(2), 183–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00187-018-0266-0.

Saunila, M., Pekkola, S., & Ukko, J. (2014). The relationship between innovation capability and performance: The moderating effect of measurement. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 63(2), 234–249.

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research Online, 8(2), 23–74.

Schreiber, J. B., Nora, A., Stage, F. K., Barlow, E. A., & King, J. (2006). Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. The Journal of Educational Research, 99(6), 323–338. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338.

Shank, J. K. (2006). Strategic cost management: upsizing, downsizing, and right(?) sizing. In A. Bhimani (Ed.), Contemporary issues in management accounting (pp. 355–379). New York: Oxford University Press.

Shields, M. D., & Young, S. M. (1994). Managing innovation costs: A study of cost conscious behavior by R&D professionals. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 6, 175–196.

Smith, D., & Langfield-Smith, K. (2004). Structural equation modeling in management accounting research: Critical analysis and opportunities. Journal of Accounting Literature, 23, 49–86.

Taipaleenmäki, J. (2014). Absence and variant modes of presence of management accounting in new product development: Theoretical refinement and some empirical evidence. European Accounting Review, 23(2), 291–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2013.811065.

Taylor, A., MacKinnon, D., & Tein, J.-Y. (2008). Tests of the three-path mediated effect. Organizational Research Methods, 11(2), 241–269.

Thompson, A. A., & Stickland, A. J. (1999). Strategic management: concepts and cases. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Uotila, J., Maula, M., Keil, T., & Zahra, S. A. (2009). Exploration, exploitation, and financial performance: Analysis of S&P 500 corporations. Strategic Management Journal, 30(2), 221–231.

van de Ven, A. H. (1986). Central problems in the management of innovation. Management Science, 32(5), 590–607.

van der Veeken, H. J. M., & Wouters, M. J. F. (2002). Using accounting information systems by operations managers in a project company. Management Accounting Research, 13(3), 345–370. https://doi.org/10.1006/mare.2002.0188.

Venkatraman, S. (2015). Business partnering. Strategic Finance, 97(2), 47–53.

Windeck, D., Weber, J., & Strauss, E. (2015). Enrolling managers to accept the business partner: The role of boundary objects. Journal of Management and Governance, 19(3), 617–653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-013-9277-2.

Wolf, S., Weißenberger, B. E., Wehner, M., & Kabst, R. (2015). Controllers as business partners in managerial decision-making: Attitude, subjective norm, and internal improvements. Journal of Accounting and Organizational Change, 11(1), 24–46.

Ylinen, M., & Gullkvist, B. (2014). The effects of organic and mechanistic control in exploratory and exploitative innovations. Management Accounting Research, 25(1), 93–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2013.05.001.

Zoni, L., & Merchant, K. A. (2007). Controller involvement in management: An empirical study in large italian corporations. Journal of Accounting and Organizational Change, 3(1), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1108/18325910710732849.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This paper has greatly benefited from the comments of Henri Dekker, Isabella Grabner, Frank Moers, Rodriguez Mendoza, Gerhard Speckbacher, Paula van Veen-Dirks, Frank Verbeeten, Jacco Wielhouwer, Eelke Wiersma, participants at the research seminar at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, and participants at the 2016 ERMAC conference in Vienna. The comments from two anonymous reviews are greatly appreciated.

Survey instrument (abbreviated)

Survey instrument (abbreviated)

1.1 Purpose of MAS

A list of 15 different management accounting systems (e.g. Budgets, non-financial performance measures, ABC, BSC, and others) has been presented to the respondents. Then the following question is asked: Management accounting techniques can be used for various purposes. In your firm, how often are the previously mentioned management accounting techniques used to do the following (1 = Never for this purpose, 2 = Seldom for this purpose, 3 = Sometimes for this purpose, 4 = Often for this purpose, 5 = Very often for this purpose, 9 = Don’t know).

Monitoring

-

1.

Track progress toward goals

-

2.

Monitor results

-

3.

Compare outcomes to expectations

Attention focusing

-

4.

Tie the organization together

-

5.

Enable the organization to focus on critical success factors

-

6.

Enable discussion in meetings

-

7.

Enable continual challenge and debate

Strategic decision making

-

8.

Make strategic decisions when an immediate response is required

-

9.

Make strategic decisions when there is enough time for analysis

-

10.

Anticipate the future direction of the company

Legitimization

-

11.

Confirm your understanding of the business

-

12.

Justify decisions

-

13.

Verify assumptions (e.g. in a business case)

-

14.

Validate your point of view

Strategy

Are the following issues more or less important to your firm, compared to the competitors in your main business (1 = Far less, 2 = Less, 3 = Similar, 4 = More, 5 = Much more, 9 = Don’t know)?

-

1.

Delivery on time

-

2.

Provide good after-sales service and support

-

3.

Products and services are always available for customers

-

4.

Provide high quality products and services

-

5.

Be flexible with production volumes

-

6.

Introduce new productsa

-

7.

Create unique product featuresa

-

8.

Customize products and services to customer needsa

-

9.

Low price

-

10.

Low production costs

aItem dropped from analysis

Roles of management accounting

How much time on average do the finance and management accounting spend on the following activities during a year in your firm? Please distribute 100 points.

-

1.

Accounting and reporting (transaction processing, aggregating financial transactions in general ledgers, financial control, preparing annual report)

-

2.

Management accounting and control (planning, forecasting, budgeting, target setting, analysis, management reporting, balanced scorecards)

-

3.