Abstract

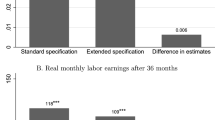

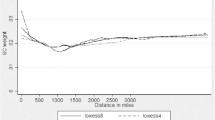

The German start-up subsidy (SUS) program for the unemployed has recently undergone a major makeover, altering its institutional setup, adding an additional layer of selection and leading to ambiguous predictions of the program’s effectiveness. Using propensity score matching (PSM) as our main empirical approach, we provide estimates of long-term effects of the post-reform subsidy on individual employment prospects and labor market earnings up to 40 months after entering the program. Our results suggest large and persistent long-term effects of the subsidy on employment probabilities and net earned income. These effects are larger than what was estimated for the pre-reform program. Extensive sensitivity analyses within the standard PSM framework reveal that the results are robust to different choices regarding the implementation of the weighting procedure and also with respect to deviations from the conditional independence assumption. As a further assessment of the results’ sensitivity, we go beyond the standard selection-on-observables approach and employ an instrumental variable setup using regional variation in the likelihood of receiving treatment. Here, we exploit the fact that the reform increased the discretionary power of local employment agencies in allocating active labor market policy funds, allowing us to obtain a measure of local preferences for SUS as the program of choice. The results based on this approach give rise to similar estimates. Thus, our results indicating that SUS are still an effective active labor market program after the reform do not appear to be driven by “hidden bias.”

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

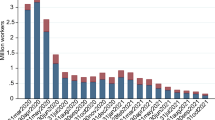

For an overview of the importance of SUS programs in OECD countries, see Fig. 1.

For example, effect estimates are provided by Tokila (2009) for Finland, Duhautois et al. (2015) for France, Caliendo and Künn (2011) and Wolff et al. (2016) for Germany, O’Leary (1999) for Hungary and Poland, Perry (2006) for New Zealand, Rodríguez-Planas and Jacob (2010) for Romania and Behrenz et al. (2016) for Sweden. An in-depth review of estimated effects and the institutional setup is given by Caliendo (2016).

For a detailed description of the program before and after the 2011 reform for the NSUS in Germany, estimated short-term program effects and a discussion of the importance of the institutional setup of the program, see Bellmann et al. (2018).

It is currently the only SUS program available to unemployment benefits I recipients. Unemployment benefits II recipients, which are mostly long-term unemployed or individuals with very sparse employment history, are eligible for a different program called “Einstiegsgeld,” which is not the focus of this study.

Participants spent on average 2.8 months in unemployment before entering the program. Our sample of non-participants was unemployed for 2.7 months on average prior to the assigned date of entry. The p value of a t-test of equality of means is about 0.22.

According to the FEA, about 7400 individuals entered the program between February and June 2012.

The significant gap between treated and comparison group characteristics is due to the fact that pre-matching was done in a very coarse way to ensure minimal overlap between the two groups.

The matching is performed using the psmatch2 ado-package by Leuven and Sianesi (2003).

In the spirit of Imai et al. (2008), a grid search is performed, choosing the bandwidth that maximizes balance by minimizing the pseudo-\(\hbox {R}^2\) after matching. We found this to be the case for \(h=0.13\).

The entire estimation procedure is repeated for each subsample. Balancing indicators and propensity score distributions for the subsamples are available upon request from the authors. Generally, matching quality is somewhat worse due to smaller sample but still within the recommended range of 3-5% in terms of mean standardized bias as given by Caliendo and Kopeinig (2008).

The interval derived by Crump et al. (2009) is optimal in the sense that it minimizes the asymptotic variance of matching estimators. Choosing \(\alpha \) involves a trade-off: Larger \(\alpha \) reduces imbalance and extrapolation leading to lower variance, while discarding information increases variance. As software implementation, we use their accompanying optselect package to obtain \(\alpha \).

The radius matching with bias adjustment is implemented using the radiusmatch package of Huber et al. (2015).

Interestingly, their results suggest a lesser role of personality traits for selection into SUS, which may indeed indicate more severe selection into treatment through caseworkers after the reform.

One additional finding of Chabé-Ferret (2015) is that it is advisable not to condition on pre-treatment characteristics in the matching process when using CDID. However, for our application, this does not make any significant difference.

There are several reasons why we are constrained to contemporaneous data for the instrument. First, data from the previous year correspond to the pre-reform program and thus measure the preference for a nonexistent program. Second, data from the month of January 2012 (the first month after the reform took place) cannot be used as the number of approved applications is contaminated by applicants from before the reform. Third, data after our sampling time frame cannot be used as there was a reform of LEA districts, which led to the disappearance of 22 LEAs. The data on applications for the program and actual entries are obtained from administrative data from the FEA.

The only difference is that we drop interaction terms as these were only included to further improve balance in X across treatment groups D. This choice does not affect our IV results in any significant manner. Results with the interaction terms included can be obtained from the authors on request.

Coefficients on personality traits and test results from the auxillary regression are shown in Table A.3.

The median corresponds to roughly a 50% leave-one-month-out approval rate.

References

Becker S, Caliendo M (2007) Sensitivity analysis for average treatment effects. Stata J 7(1):71–83

Behrenz L, Delander L, Månsson J (2016) Is starting a business a sustainable way out of unemployment? Treatment effects of the Swedish start-up subsidy. J Labor Res 37(4):389–411

Bellmann L, Caliendo M, Tübbicke S (2018) The post-reform effectiveness of the new German start-up subsidy for the unemployed. LABOUR 32(3):293–319

Bernhard S, Grüttner M (2015) Der Gründungszuschuss nach der Reform: Eine qualitative Implementationsstudie zur Umsetzung der Reform in den Agenturen. Forschungsbericht 4/2015, IAB Nürnberg

Blundell R, Costa Dias M (2009) Alternative approaches to evaluation in empirical microeconomics. J Hum Resour 44(3):565–640

Busso M, DiNardo J, McCrary J (2014) New evidence on the finite sample properties of propensity score reweighting and matching estimators. Rev Econ Stat 96(5):885–897

Caliendo M (2016) Start-up subsidies for the unemployed: opportunities and limitations. IZA World Labor 200:1–11

Caliendo M, Kopeinig S (2008) Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. J Econ Surv 22(1):31–72

Caliendo M, Künn S (2011) Start-up subsidies for the unemployed: long-term evidence and effect heterogeneity. J Public Econ 95(3–4):311–331

Caliendo M, Künn S (2014) Regional effect heterogeneity of start-up subsidies for the unemployed. Reg Stud 48(6):1108–1134

Caliendo M, Künn S (2015) Getting back into the labor market: the effects of start-up subsidies for unemployed females. J Popul Econ 28(4):1005–1043

Caliendo M, Fossen F, Kritikos A (2014) Personality characteristics and the decisions to become and stay self-employed. Small Bus Econ 42(4):787–814

Caliendo M, Künn S, Weissenberger M (2016) Personality traits and the evaluation of start-up subsidies. Eur Econ Rev 86:87–108

Chabé-Ferret S (2015) Analysis of the bias of matching and difference-in-difference under alternative earnings and selection processes. J Econ 185(1):110–123

Crump R, Hotz VJ, Imbens GW, Mitnik OA (2009) Dealing with limited overlap in estimation of average treatment effects. Biometrika 96(1):187–199

DiPrete T, Gangl M (2004) Assessing bias in the estimation of causal effects: Rosenbaum bounds on matching estimators and instrumental variables estimation with imperfect instruments. Sociol Methodol 34:271–310

Duhautois R, Redor D, Desiage L (2015) Long term effect of public subsidies on start-up survival and economic performance: an empirical study with French data. Rev Écon Ind 149(1):11–41

Dunn T, Holtz-Eakin D (2000) Financial capital, human capital, and the transition to self-employment: evidence from intergenerational links. J Labor Econ 18:282–305

Frölich M (2007) Nonparametric IV estimation of local average treatment effects with covariates. J Econ 139(1):35–75

Heckman JJ, Robb R (1985) Alternative methods for evaluating the impact of interventions: an overview. J Econ 30(1):239–267

Heckman JJ, Ichimura H, Todd P (1997) Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator: evidence from evaluating a job training programme. Rev Econ Stud 64(4):605–654

Heckman JJ, Stixrud J, Urzua S (2006) The effects of cognitive and noncognitive abilities on labor market outcomes and social behavior. J Labor Econ 24:411–482

Huber M, Lechner M, Wunsch C (2013) The performance of estimators based on the propensity score. J Econ 175(1):1–21

Huber M, Lechner M, Steinmayr A (2015) Radius matching on the propensity score with bias adjustment: tuning parameters and finite sample behavior. Empir Econ 49(1):1–13

Imai K, King G, Stuart EA (2008) Misunderstandings between experimentalists and observationalists about causal inference. J R Stat Soc Ser A 171(2):481–502

Imbens G, Angrist JD (1994) Identification and estimation of local average treatment effects. Econometrica 62(2):467–75

Imbens GW, Wooldridge JM (2009) Recent developments in the econometrics of program evaluation. J Econ Lit 47(1):5–86

Lechner M (2001) Identification and estimation of causal effects of multiple treatments under the conditional independence assumption. In: Econometric evaluation of labour market policies. Physica-Verlag, Heidelberg, pp 43–58

Lechner M, Strittmatter A (2017) Practical procedures to deal with common support problems in matching estimation. Discussion Papers 10532, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), Bonn

Lechner M, Wunsch C (2013) Sensitivity of matching-based program evaluations to the availability of control variables. Labour Econ 21:111–121

Lechner M, Miquel R, Wunsch C (2011) Long-run effects of public sector sponsored training in West Germany. J Eur Econ Assoc 9(4):742–784

Leuven E, Sianesi B (2003) PSMATCH2: stata module to perform full Mahalanobis and propensity score matching, common support graphing, and covariate imbalance testing. Technical report, Statistical Software Components S432001, Boston College Department of Economics, Revised 30 April 2004

Lindquist M, Sol J, van Praag M, Vladasel T (2016) On the origins of entrepreneurship: evidence from sibling correlations. CEPR Discussion Papers 11562, C.E.P.R. Discussion Papers

Liu C (2005) Robit regression: a simple robust alternative to logistic and probit regression. Wiley, Hoboken, pp 227–238

MacKinnon JG (2006) Bootstrap methods in econometrics. Econ Rec 82:2–18

OECD (2015) Public expenditure and participant stocks on LMP. OECD, Stat Database

O’Leary CJ (1999) Promoting self employment among the unemployed in Hungary and Poland. Working Paper 99-55, W. E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research

Perry G (2006) Are business start-up subsidies effective for the unemployed: evaluation of enterprise allowance. Working paper, Auckland University of Technology

Rodríguez-Planas N, Jacob B (2010) Evaluating active labor market programs in Romania. Empir Econ 38(1):65–84

Rosenbaum PR (2002) Observational studies, 2nd edn. Springer, New York

Rosenbaum P, Rubin D (1983) The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 70(1):41–55

Roy AD (1951) Some thoughts on the distribution of earnings. Oxf Econ Pap 3(2):135–146

Rubin D (1974) Estimating causal effects of treatments in randomised and nonrandomised studies. J Educ Psychol 66(5):688–701

Rubin DB (2001) Using propensity scores to help design observational studies: application to the tobacco litigation. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol 2(3):169–188

Sauerbrei W, Royston P (1999) Building multivariable prognostic and diagnostic models: transformation of the predictors by using fractional polynomials. J R Stat Soc Ser A (Stat Soc) 162(1):71–94

Sianesi B (2004) An evaluation of the Swedish system of active labour market programmes in the 1990s. Rev Econ Stat 86(1):133–155

Staiger D, Stock JH (1997) Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments. Econometrica 65(3):557–586

Tokila A (2009) Start-up grants and self-employment duration. Working paper, School of Business and Economics, University of Jyväskylä

Wolff J, Nivorozhkin A, Bernhard S (2016) You can go your own way! The long-term effectiveness of a self-employment programme for welfare recipients in Germany. Int J Soc Welf 25(2):136–148

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The authors thank Lutz Bellmann, two anonymous reviewers, the editor and participants at the 7th ifo Dresden Workshop on Labour Economics and Social Policy, the University of Barcelona’s Workshop on Unemployment and Labor Market Policies, the 2017 conference of the European Society for Population Economics, the LISER workshop on Causal Inference, Program Evaluation, and External Validity, and the 2017 conference of the European Association of Labor Economists for helpful discussions and valuable comments. We are grateful to the Institute for Employment Research (IAB) for cooperation and institutional support within the research Project No. 1755.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Caliendo, M., Tübbicke, S. New evidence on long-term effects of start-up subsidies: matching estimates and their robustness. Empir Econ 59, 1605–1631 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-019-01701-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-019-01701-9