Abstract

Major economic, environmental, or social shocks induce uncertainty, which in turn may impact economic development and may require institutional change. Based on the idea that catastrophic events (CEs) affect people’s perceptions of reality and judgments about the future, this paper analyzes the effect of CEs on people’s worries in terms of social, economic, and environmental issues. In particular, we consider the terrorist attack 9/11 in 2001, the beginning of the financial crisis in 2008, and the nuclear disaster in Fukushima in 2011. We propose two possible mechanisms: A CE in one sphere may affect people’s worries in general (“spillover”) or it may lead to people focusing on that sphere and being less worried about other spheres (“crowding out”). We argue that the determinants of the mechanisms are related to the type of CE, that a person’s professional background moderates the influence of a CE on his or her worries, and that the subsequent development of worries is affected by whether institutional responses are contested. The analysis is based on longitudinal data of the German Socio-Economic Panel.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This approach, of course, causes some uncertainty as to whether people were already aware of the CE at the time of the interview. We check this assumption in a robustness test in “Appendix B”.

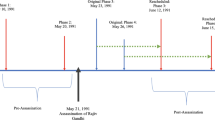

By contrast, a long-term general linear trend spanning the entire sample period from 1999 to 2013 will suffer from shifts and breaks of linearity due to a mixture of external influences on people’s worries. In addition, the assumption of time-constant unobserved heterogeneity can no longer be justified. Further, restricting the analysis to those individuals continuously surveyed for 15 years would substantially reduce sample size, cf. “Appendix B”.

Note that the variance of the daily worry averages increases in the course of each calendar year according to the clustering of interview dates towards the beginning of the year.

The nomenclature will soon become clear later on in this section.

For the sake of clarity our notation implies a slight redundancy at this point. Formally, worries \( y_{it,v \cdot } \) may be attributed to a certain CE w only tentatively by relying on temporal proximity. To put it simply, we do not know the source, i.e. the trigger-CE of a person’s worries, cf. the discussion at the end of Sect. 3. We still stick with the index w in \( y_{it,vw} \) as it serves to distinguish the models for different CEs.

This assumption will be relaxed in Sect. 5 by panel-robust statistical inference.

Note that, in spite of the individual effects \( \alpha_{i} \) included in the above equation, the errors \( \varepsilon_{it} \) are potentially correlated over t for a given individual i (serial correlation), and heteroscedastic. For this reason, panel-robust errors were specified in Stata.

This number is based on an average environmental worry level of 1.09 as of 2001 (cf. Table 2) and the corresponding reduction of 0.182 units given by the \( \beta_{1} \) estimate.

This number corresponds to the vertex of the simple quadratic equation involving the terms months and months2 (with coefficients \( \beta_{2} \) and \( \beta_{3} \), respectively). The x-coordinate of the vertex is given by \( {-}\beta_{2} /\left( {2\beta_{3} } \right) \), i.e. 11 months after the CE, for environmental worries. The worry level at this vertex is given by \( \beta_{1} - \beta_{2}^{2} /\left( {4\beta_{3} } \right) \). See also Lind and Mehlum (2010).

References

Abou-Taam M (2011) Folgen des 11. September 2001 für die deutschen Sicherheitsgesetze. APuZ 61:9–14

Allison PD (1994) Using panel data to estimate the effects of events. Sociol Methods Res 23:174–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124194023002002

Askitas N, Zimmermann KF (2009) Google econometrics and unemployment forecasting. Appl Econ Q 55:107–120

Balli HO, Sørensen BE (2013) Interaction effects in econometrics. Empir Econ 45:583–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-012-0604-2

BBC News (2003) Suspect ‘reveals 9/11 planning’. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/3128802.stm. Accessed 5 Nov 2016

Beck U (2006) Living in the world risk society. Econ Soc 35:329–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085140600844902

Berger EM (2010) The Chernobyl disaster, concern about the environment, and life satisfaction. Kyklos 63:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6435.2010.00457.x

Bloom N (2009) The impact of uncertainty shocks. Econometrica 77:623–685. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA6248

Bratberg E, Monstad K (2015) Worried sick? Worker responses to a financial shock. Labour Econ 33:111–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2015.02.003

Braumoeller BF (2004) Hypothesis testing and multiplicative interaction terms. Int Organ 58:807–820. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818304040251

Bundesfinanzministerium (2015) Ueberpruefung von Regulierungsmaßnahmen im Finanzmarkt. Bericht an den Finanzausschuss des Deutschen Bundestags. https://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/DE/Standardartikel/Themen/Internationales_Finanzmarkt/Finanzmarktpolitik/Finanzmarktregulierung/2015-08-07-finanzmarktregulierung-bericht.html. Accessed 5 Nov 2016

Bundesregierung (2011) Der Weg zur Energie der Zukunft. http://www.bundesregierung.de/ContentArchiv/DE/Archiv17/Regierungserklaerung/2011/2011-06-09-merkel-energie-zukunft.html. Accessed 5 Nov 2016

Christelis D, Georgarakos D (2013) Household economic decisions under the shadow of terrorism. SSRN Electron J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1317086

Christelis D, Georgarakos D, Jappelli T (2015) Wealth shocks, unemployment shocks and consumption in the wake of the Great Recession. J Monet Econ 72:21–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2015.01.003

Cochrane H (1995) The economic impact of earthquake disasters. In: Centre for Advanced Engineering, Earthquake Commission (ed) The challenge of rebuilding cities. Centre for Advanced Engineering and the Earthquake Commission, Wellington, pp 65–80

Davies W, McGoey L (2012) Rationalities of ignorance: on financial crisis and the ambivalence of neo-liberal epistemology. Econ Soc 41:64–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2011.637331

Elster J (1998) A plea for mechanisms. In: Hedström P, Swedberg R (eds) Social mechanisms: an analytical approach to social theory. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 45–73

Ferrer-i-Carbonell A, Frijters P (2004) How important is methodology for the estimate of the determinants of happiness? Econ J 114:641–659

Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (2011) The financial crisis inquiry report. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC

Goebel J, Krekel C, Tiefenbach T, Ziebarth NR (2013) Natural disaster, policy action, and mental well-being: the case of Fukushima. In: IZA discussion paper series, pp 1–43

Goebel J, Krekel C, Tiefenbach T, Ziebarth NR (2014) Natural disaster, environmental concerns, well-being and policy action: the case of Fukushima

Goebel J, Krekel C, Tiefenbach T, Ziebarth NR (2015) How natural disasters can affect environmental concerns, risk aversion, and even politics: evidence from Fukushima and three European countries. J Popul Econ 28:1137–1180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-015-0558-8

Hacker JS, Rehm P, Schlesinger M (2013) The insecure American: economic experiences, financial worries, and policy attitudes. Perspect Politics 11:23–49. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592712003647

Hobolt SB, Wratil C (2015) Public opinion and the crisis: the dynamics of support for the euro. J Eur Public Policy 22:238–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.994022

Huang L, Zhou Y, Han Y, Hammitt JK, Bi J, Liu Y (2013) Effect of the Fukushima nuclear accident on the risk perception of residents near a nuclear power plant in China. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:19742–19747. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1313825110

Im EI, Cauley J, Sandler T (1987) Cycles and substitutions in terrorist activities: a spectral approach. Kyklos 40:238–255

Jasanoff S (1993) Bridging the two cultures of risk analysis. Risk Anal 13:123–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.1993.tb01057.x

Kenourgios D, Dimitriou D (2015) Contagion of the global financial crisis and the real economy: a regional analysis. Econ Model 44:283–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2014.10.048

Köcher R (2011) Eine atemraubende Wende: Die Reaktionen der Politik auf die Katastrophe von Fukushima haben die Abwendung der Deutschen von der Atomkraft beschleunigt. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 5

Köcher R (2013) Banken in der öffentlichen Wahrnehmung: Ergebnisse einer repräsentativen Befragung im Auftrag des Bundesverbands deutscher Banken. https://bankenverband.de/media/files/Umfrageergebnis_9e01sBY.pdf. Accessed 5 Nov 2016

Lind JT, Mehlum H (2010) With or without U? The appropriate test for a U-shaped relationship. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 72:109–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0084.2009.00569.x

MacGregor D (1991) Worry over technological activities and life concerns. Risk Anal 11:315–324

Miko FT, Froehlich C (2004) Germany’s role in fighting terrorism: implications for U.S. Policy. Congressional Research Service, Washington, DC

North DC (1992) Institutions and economic theory. Am Econ 36:3–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13398-014-0173-7.2

NYT (2001) Nation plunges into fight with enemy hard to identify. New York Times

Owen AL, Wu S (2007) Financial shocks and worry about the future. Empir Econ 33:515–530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-006-0115-0

Riedl M, Geishecker I (2014) Keep it simple: estimation strategies for ordered response models with fixed effects. J Appl Stat 41:2358–2374. https://doi.org/10.1080/02664763.2014.909969

Schüller S (2016) The effects of 9/11 on attitudes toward immigration and the moderating role of education. Kyklos 69(4):604–632. https://doi.org/10.1111/kykl.12122

Schultz WP (2001) The structure of environmental concern: concern for self, other people, and the biosphere. J Environ Psychol 21:327–339. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.2001.0227

Scott WR (2013) Institutions and organizations: ideas, interests, and identities. Sage Publications, Los Angeles

Sjöberg L (1998) Worry and risk perception. Risk Anal 18:85–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.1998.tb00918.x

Sjöberg L (2004) Principles of risk perception applied to gene technology. EMBO Rep 5:47–51

Slovic P, Fischhoff B, Lichtenstein S (1982) Why study risk perception? Risk Anal 2:83–93

Spielberger CD, Vagg PR, Barker LR, Donham GW, Westberry LG (1980) The factor structure of the state-trait anxiety inventory. In: Sarason IG, Spielberger CD (eds) Stress and anxiety. Hemisphere, New York, pp 95–109

StataCorp (2013) Stata statistical software: release 13. StataCorp LP, College Station

Visschers VHM, Siegrist M (2013) How a nuclear power plant accident influences acceptance of nuclear power: results of a longitudinal study before and after the Fukushima disaster. Risk Anal 33:333–347. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1313825110

Wagner GG, Frick JR, Schupp J (2007) The German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP): scope, evolution and enhancements. Schmollers Jahrb 127:139–169

Wilkinson I (1999) News media discourse and the state of public opinion on risk. Risk Manag 1:21–31. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.rm.8240029

Wooldridge JM (2010) Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data, 2nd edn. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Further results

Appendix B: Robustness checks

In order to test for sample attrition and entry effects over the entire 15-year period ranging from 1999 to 2013 (including the 2-year “9/11” preliminary period and the 2-year “Fukushima” follow-up period), we re-estimate the model using a complete sample, i.e., people interviewed in each of the 15 years. Results for the one-time level effects (\( \beta_{1} \), cf. Sect. 4) are included in Table 5, which excludes all other covariates for brevity. For the “9/11” CE, magnitude and significance levels of the coefficients do not change as compared to Table 3. The same holds true for “Lehman” and “Fukushima,” with two exceptions of changing significance levels. Hence, our results are fairly robust as to sample composition over time.

Next, we check sensitivity as to the exact interview date. We introduce an artificial error (normal distribution with μ = 0 and σ = 1) to the recorded date in order to attenuate potential dependencies between CE and interview date. Table 5 shows that results are virtually robust as compared to Table 3. In addition, we rerun our analysis after removing all interviews carried out on the particular day of the respective CE with special attention to the “Fukushima” CE, where a number of 90 interviews were conducted on March 11, 2011. Results in Table 5 show that no distorting effects are to be expected.

Further, we consider the influence of the chosen two-year follow-up period for each CE. We re-estimate the model using a one-year and a three-year follow-up scenario, respectively. As to the shortened one-year follow-up period, there are three marked discrepancies compared to our previous results. For the “9/11” CE the \( \beta_{1} \) level effect estimate loses its significance for environmental worries. As to the “Lehman” and “Fukushima” CEs, the estimates for social worries turn significant. We conclude that our model is most affected by a shortening of the follow-up period requiring some time to capture the nonlinear evolution of worries following a CE. As to the extended three-year follow-up period, however, results are largely in line with Table 3 (where two estimates marked by “NA” are not available due to numerical instability). All in all, a two-year follow-up period as applied in Sect. 5 appears to be a reasonable choice, as results tend to stabilize upon extension to a three-year follow-up, see also Goebel et al. (2014).

Next, note that the main effect (i.e., not interacted with CE) of (nearly) time-invariant variables such as sex or education is generally not identified in FE models (in contrast to time-varying interaction effects). As a robustness check we will include a random effects (RE) estimator instead of the FE estimator applied in Sect. 5. The RE level effects displayed in Table 5 are in broad agreement with the FE results of Table 3. Hence, we may avoid the more sensitive RE assumptions which, in addition, are clearly rejected by a Hausman test (also included in Table 5). See e.g., Wooldridge (2010) for further technical details and precise assumptions of the FE and RE approaches.

Finally, we test whether our findings are robust to an ordered probit model (using Stata’s xtoprobit) in order to challenge the cardinality assumption introduced in Sect. 4. Note that, due to the nonlinear structure of the probit model, only the coefficients’ sign and significance can be compared. With this in mind, results appear to be robust against the linear model. Due to numerical instability the result for economic worries following the Fukushima CE is not available.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ehlert, A., Seidel, J. & Weisenfeld, U. Trouble on my mind: the effect of catastrophic events on people’s worries. Empir Econ 59, 951–975 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-019-01682-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-019-01682-9

Keywords

- Catastrophic event

- Institutional change

- Social

- Economic

- Environmental

- Worries

- Professional background

- GSOEP

- Spillover

- Crowding out

- Panel data