Abstract

In this paper, the results of an experimental campaign of cryogenic milling are presented and discussed. For this purpose, a specific experimental setup that allowed to feed the liquid nitrogen LN through the tool nozzles was used. Tool life tests were carried out at different cutting speeds. The tool duration data were collected and used to identify the parameters of the Taylor’s model. Different end-of-life criteria for the tool inserts were even investigated. The achieved results are compared to those obtained using conventional cooling. It was observed that at low cutting velocity, conventional cooling still assures longer tool lives than in cryogenic condition. Since in cryogenic milling the increasing of the cutting velocity is not so detrimental as in conventional cutting, at high cutting speed (from 125 m/min) longer tool durations can be achieved. Statistical analyses on the model parameters were carried out to confirm the presented findings. The analysis of the effect of the cooling approach on the main wear mechanisms was also reported. At low cutting speed, adhesion and chipping phenomena affected the tool duration mainly in cryogenic milling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the last decade, sustainability has been one of the main research pillars in several fields, including manufacturing.

As reported by Abdelrazek et al. in [1], cryogenic machining is one of the sustainable and profitable alternatives to conventional cooling for processing titanium and other heat-resistant alloys HRA. Jawahir et al. [2] carried out an exhaustive analysis of the state of art on cryogenics in manufacturing.

Shokrani et al. in [3] focused their attention to machining processes, especially with respect to hard-to-cut materials like titanium- and nickel-based alloys (HRA) that are widely used in several applications, ranging from aerospace to medical industries. Indeed, the use of cryogenics (mainly CO2 or liquid nitrogen LN) as an alternative cooling lubrication CL methodology reduces most of the environmental/economic issues connected to the oil-based cooling solutions as well as gets rid of the health issues linked to the connected hazard mist [4, 5]. Albertelli et al. [6] carried out an energy assessment of different cooling lubricating approaches. They found that cryogenic cooling even allows reducing the energy consumption at the machine tool perspective.

Several research studies were first carried out focusing on turning. In many of these works, cryogenic machining was compared to dry cutting that is far from being a feasible solution in real applications, especially if HRAs need to be processed, Rotella et al. [7].

Although the use of liquid nitrogen LN is particularly promising as cutting coolant, its continuous and stable delivery in the cutting region through tool nozzles is not trivial. Indeed, complex phenomena such as vaporization and cavitation can negatively affect a stable and reliable flow of LN. In milling, these issues are even more detrimental due to the rotation of the tool. Therefore, the cryogenic technology is not ready and mature for being used in shop floors, Jawahir et al. [2].

The optimization of the delivery system in terms of number, orientation, and position of the cryogenic jets together with the setup alternatives was some of the studied issues, for instance in Balaji et al. [8]. Tahmasebi et al. [9] developed a computational fluid dynamics (CFD) model for studying the feeding system and the LN jets coming from the mill nozzles.

The analysis of the effects of cryogenic cooling on cutting forces, friction, cutting temperatures, and chip morphology is another relevant research branch in this field [10, 11]. Moreover, even the characteristics (i.e., surface roughness, residual stresses, micro-hardness, material microstructural changes) of the processed surfaces in cryogenic turning were analyzed, Sivaiah and Chakradhar [12]. It was confirmed that in most of the cases, cryogenic turning assures better surface specifications if compared to other CL methods.

For what concerns the effect the cryogenic cooling on the life of the tools, the enhancement of the tool duration was observed in some works, but it seems strongly related to the specific used delivery system and to the selected cutting parameters. For instance, Strano et al. in [13] observed an increment of 40% (machining at 50 m/min, feed 0.3 mm/rev and using an optimized tool for LN) with respect to wet turning. Higher improvements (200%) were observed by Wang and Rajurkar in [10] but performing wear tests at very high cutting speeds (130 m/min with a lower feed 0.2 mm/rev). Intermediate results were observed in Jun [14] that tested some solutions to optimize the penetration of the LN jets into the tool-chip interface. The author even demonstrated that cryogenic cooling reduces the tool-workpiece friction.

In order to improve the knowledge on cryogenics in turning, a few studies focused on the finite element (FE) modeling were carried out [15,16,17]. Although many works on cryogenic turning have been developed, the literature is rather poor for what concerns the use of cryogenic in milling, especially if the performance assessment with respect to the industrial reference solutions (wet machining) is of interest.

For instance, Sadik et al. [18] carried out an experimental campaign in which cryogenic and wet milling were compared. In this research, the CO2 was adopted as cryogenic coolant. Indexable mill with physical vapor deposition (PVD)–coated inserts were used. They found that for a specific nozzle configuration, the life of the tool can be extended up to 4 times. It was found that other setups were not so effective.

In [19], Pereira et al. studied the effects of lubri-coolant technologies on the cutting performance in contour milling. More specifically, the authors compared traditional cooling (wet) with a combination of cryogenic and MQL (minimum quantity lubrication) and MQL. Cutting tests were carried out on Inconel 718. It was observed that although wet machining involved highest cutting forces, it assured the longest tool lives.

In Lu et al. [20], an innovative tool for cryogenic (liquid nitrogen) milling was developed. The same authors in [21] investigated the sustainability of the cryogenic cooling technology. Cutting data were gathered in a shop-floor where, for the limitations linked to production constraints, dedicated tool life tests were not feasible. Moreover, some information on the adopted tools and on the cutting parameters are missing. Although the adopted approach was not suitable for doing a scientific and rigorous analysis, a moderate enhancement was observed.

In [22], Pittalà carried out an experimental study on the effects of a CO2-based cryogenic coolant of end-milling of Ti6Al4V. A coated tungsten carbide with 10% cobalt tool was used. Moreover, the authors tested some different inner tool channel configurations both testing cryogenic cooling and wet cutting. The performed analysis showed that the cutting performance in terms of flank wear depends on the selected tool. More specifically, a moderate reduction of the flank wear was observed only for one of the tested configurations. As can be noted, the effect of cryogenic cooling on tool life is not univocal. Indeed, the reported results refer to different cryogenic cooling strategies, different tools, and operating parameters.

Although it was observed, from the literature developed on turning, that the LN is the most promising cryogenic solution, only one research investigated the potentialities of such cryogenic solution in milling, Lu et al. [21]. Moreover, in that work, only a rough comparison with respect to conventional cooling was performed. Due to this lack of knowledge, a wide use of cryogenic in milling is far from being accomplished.

In order to bridge this gap, in this work, tool wear tests were carried out in cryogenic (LN) and conventional cooling conditions. In both the cases, the coolant was delivered through the inner nozzles of a commercial indexable cutter. For this purpose, a specific cryogenic setup was developed and installed on a 5-axes machine. The worn inserts were analyzed and compared. The tool life data were gathered and used to develop a Taylor’s model for both the studied CL methodologies. Statistical analyses were carried out to corroborate the findings.

The paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, all the details of the developed cryogenic setup, together with the information linked to the tooling systems and the adopted cutting parameters, are provided. In Section 3, the results of the experimental campaign were analyzed and discussed.

2 Materials and methods

In this section, a detailed description of the developed setup and of all the performed considerations needed for designing the experiments is presented.

2.1 Experimental setup

A cryogenic setup was conceived and developed. It was installed and tested on a 5-axes machine tool (Flexi model by Sigma, FFG group) (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). Figure 1a shows the main parts of the cryogenic feeding line. A flexigas (pressurized liquid nitrogen reservoir, Fig. 1b) was placed on the back of the machine. The associated piloting electro-valve, a vacuum jacket flexible pipe, and a phase separator that is used to purge the evaporated nitrogen in the feeding line due to both heat transfer and cavitation phenomena are also visible.

Figure 2a shows how the end part of the feeding line was integrated with the machine. Indeed, the developed solution allows the spindle head tilting. Figure 2a shows how the workpiece held on the force dynamometer and how it was fixed on the machine table. In Fig. 2b, details of the cryogenic head are shown. In particular, the connections of the head to the spindle and to the end part of the feeding line are visible.

The described cryogenic setup was even equipped with some sensors: a pressure sensor installed at the output of the cryogenic reservoir, a pressure sensor placed close to cryogenic head, and a dynamometer that was used to hold the cryogenic reservoir and to measure its weight variation during the experiments. More specifically, the pressure sensor closer to the head was used to measure the delivery pressure of the liquid nitrogen and to monitor the continuity of the liquid nitrogen flow during the cutting tests. The mass flow rate in cryogenic cutting was estimated exploiting subsequent flexigas weight measurements. It was observed that averagely the mass flow rate was about \( {\dot{m}}_{LN}=45\mathrm{kg}/\mathrm{h} \) for the selected pressure set point, Table 1. Several tests were performed in order to assess the quality and the stability of the jets of liquid nitrogen.

For what concerns the tests performed with the coolant, a pressure of 40 bar was set for the pump. In such conditions, the observed flow rate was equal to \( {\dot{m}}_{\mathrm{coolant}}=2770\ \mathrm{kg}/\mathrm{h} \) (measured using a flow sensor).

A Kistler force dynamometer (9255B) with the corresponding amplifier (5070A) were used for acquiring and real-time monitoring the tool and the process conditions during the wear tests.

As reported in Fig. 2a, the processed workpiece (230×230×300mm) held on the Kistler dynamometer.

Referring to the cutting strategy, in order to limit the influence of the workpiece engagement-disengagement on the tool life, a specific part-program was conceived. The cutting strategy was optimized assuring that during the change of the feed direction (i.e., workpiece corner) the tool remains in contact with the workpiece keeping a constant load (constant stepover offsetting). This was done using an approach similar to the one reported in Jacso et al. [23]. Moreover, when it was requested to stop the cutting to analyze the tool (for a scheduled stop or for a supplementary check), it was smoothly disengaged from the piece with a circular trajectory.

During each milling run, the cutting forces were constantly monitored to fast react to possible abrupt tool deterioration. In case, the cutting was immediately stopped as described. The developed part program allowed recording the final position of the tool and starting again from the last saved position to further continue the experiments.

At each stop, all the inserts were analyzed (flank wear) with a Stereomicroscope Optika SZN-T with Motic SMZ 168T. A fast rough evaluation of the flank width was performed during the experimentation (Fig. 3). Another indirect sign used to assess the wear of the tool was the presence of marks (uncut material) left on the machined surface. These evaluations were done to decide to stop the run or to continue cutting. It is worth noting that a more accurate analysis of the flank wear was carried out post-processing the images of the worn inserts. More specifically, the tool life TL for each insert was computed (refer to Eq. 2 and Fig. 4) considering the following different end-of-life criteria:

-

Average flank width threshold VBt = 0.2mm (that can be considered “small cutting time” according to ISO 8688-1 [24])

-

Average flank width threshold VBt = 0.3mm (that can be considered “medium cutting time” according to ISO 8688-1 [24])

-

Average flank width threshold VBmt = 0.7mm (that can be considered “small cutting time,” ISO 8688-1 [24])

Fig. 3

This was done to study the effects of the end-of-life criteria on the achieved results.

The flank wear width was analyzed according to ISO standard 3685 [25], Fig. 3.

For the generic ith tested insert, a set of m VB (or maximum flank width VBm) measurements was available \( \overline{V{B}_i}=\left\{V{B}_{i1},V{B}_{i2},\cdots, V{B}_{ik},\cdots V{B}_{ip},V{B}_{i\left(p+1\right)},V{B}_{im}\right\} \) where VBik is the generic kth measurement of the average flank width (performed after the kth stop) of the ith insert. The VBik was computed using Eq. 1 where \( \mathrm{V}{\mathrm{B}}_{\mathrm{i}{\mathrm{k}}_{\mathrm{j}}} \) is the generic local measurement of the flank width; see Fig. 3.

Integrating the \( \mathrm{V}{\mathrm{B}}_{\mathrm{i}{\mathrm{k}}_{\mathrm{j}}} \) over the length lBik of the analyzed region, the area Aik of the wear land and the VBik can be computed. The tool life of each single insert TLi can be estimated linearly interpolating two subsequent cutting times (CTip and CTi(p + 1)) that were associated respectively at the pth and the (p+1)th stops. VBip and VBi(p + 1) fulfill the relationship reported in Eq. 3 where VBt is the considered threshold on the average flank width. Equations analogous to Eq. 2 and Eq. 3 were used for computing the TLi when the maximum flank width VBm was considered the selected end-of-life criterion.

2.2 Design of experiments

In this section, more details on the utilized tool and the selected cutting parameters are presented.

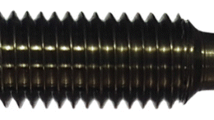

2.2.1 Tool selection

For this study, a high feed tool was selected. This tool is generally used by aerospace manufacturing companies for machining some features of air frames. Specifically, face and side milling operations can be carried out, ranging from roughing to semi-finishing. Since this tool is highly recommended by tool manufacturers for achieving high cutting performance in terms of productivity, it was decided to focus this research on this cutting solution. So far, the performance of this kind of tool with the use of cryogenic cooling has not been assessed. In this paper, a 20-mm diameter tool with Z=3 inserts from Mitsubishi (Tool body AJX06R203SA20S and JOMT06T216ZZER-JL MP9140) was selected for executing the experiments. The inserts (carbide substrate and PVD coating characterized by an Al-rich (Al,Ti)N single layer) were selected. According to the tool manufacturer, the cemented carbide substrate was designed also for providing improved crack propagation resistance. This is a brand-new grade, specifically designed by Mitsubishi for machining titanium alloys and other HRA. It was decided to perform comparative wear tests among cryogenic cooling and conventional cooling (obtained mixing water with a synthetic metalworking fluid with a volume ratio of 12%). As already reported, the literature is poor of such comparisons.

2.2.2 Cutting parameters

In Table 1, the tested cutting conditions were reported. Three cutting velocity vc levels were considered (50 m/min, 70 m/min, and 125 m/min). According to the specific literature, it was decided to consider only the dependence of the tool life TL on the cutting speed, neglecting the effect of the feed.

The other utilized cutting parameters are reported in Table 2 where ap is the axial depth of cut, ae is the radial tool-workpiece engagement, and fz is the feed per tooth. All the cutting experiments were carried out in down-milling conditions.

3 Results and discussions

In this section, the results of the experimental campaign were reported and critically analyzed. For all the tests (resumed in Table 1), the flank wear data VBik (where ith is associated to the considered test condition-insert combination) together with the VBmik measurements were computed and collected. For sake of brevity, only the average flank width data are presented in Figs. 5 and 6. More specifically, Fig. 5 shows the average flank evolution observed in the cryogenic cutting tests while Fig. 6 refers to the conventional tests. In both the pictures, the tested condition (Table 1) and the considered inserts (ins#1, ins#2, and ins#3) were specified.

The durations TLi of the tested inserts (computed using Eqs. 2 and 3) are summarized in Tables 3 and 4. Specifically, Table 3 (in accordance with ISO 8688-1 [24]) refers to what was supposed to be a small testing time considering, as end-of-life criteria, the average flank width VBt=0.2 mm and the maximum width VBmt=0.7 mm, see also Section 2.

Table 4 refers to what was supposed to be a medium testing time (VBt=0.3 mm). In such case, the homologous VBmt was not considered since it is very high and it was risky to extend the cutting tests to such end-of-life criterion.

The data were analyzed through linear regressions, see Section 3.1 for further details.

The flank wear of the three (ins#1, ins#2, ins#3) inserts at the end of each single run is reported in Table 5.

It is worth noting that, from the phenomenological perspective, the wear aspect observed on the inserts used for cryogenic cutting seems different from the wear visible on the inserts used in conventional cooling condition.

It seems that in all the cryogenic tests, the processed material was stuck on the worn insert flank. This phenomenon was not observed on the insert used for conventional cutting. This difference is less pronounced in the tests carried out at high cutting velocity (125 m/min). Its interpretation could refer to a higher adhesion phenomenon, amplified in the low cutting speed range. Some chipped portions of the tool can even be appreciated (i.e., test 5, ins#2 and ins#3) how it was brought to the well-known built-up edge phenomenology. These findings were not observed in conventional cooling, especially at low cutting velocity where the wear appears regular and the worn cutting-edge profile rather smooth.

3.1 Model development

In this section, the tool life data were exploited for identifying the Taylor’s law (Eq. 4) coefficients (C and n) through a linear regression procedure (Eqs. 5–7), Montgomery [26]. The analysis was carried out exploiting all the TLi data presented at the beginning of this paragraph (Table 3 and Table 4).

First, the Taylor’s equation was converted into a logarithmic scale as shown below.

And it was generalized as reported in Eq. 6:

where β is the vector of the unknown regression coefficients (β0 and β1), X is the vector of the regressor variables, and y is the vector that contains the response variables (in this case, the tool life durations TLi). The analysis of variance (ANOVA) (Montgomery [26]) for all the studied cases were carried out. DF, Adj SS, Adj MS, F-value, and P-value are respectively the degrees of freedom, the adjusted sum of square, the adjusted mean of square, the Fisher statistics, and the linked P-value that were all used to assess the adequacy of the performed regressions.

According to the linear regression theory, the estimation of \( {\hat{\beta}}_0 \) and \( {\hat{\beta}}_1 \) was computed using the following equation.

For all the performed regressions (changing the end-of-life criterion and considering the two cooling approaches), the standard error (SE) of the coefficients, the T Student statistics, and the linked P-values were also computed as well as the R2 and the R2-adjusted coefficients, resumed Table 19.

The regression curves, together with their 95% confidence interval CI, were plotted to appreciate the matching with the experimental data. The CI estimation on the mean response (Eq. 8) evaluated in a specific point x0 (in this case for a defined cutting velocity vc0) can be used for comparing the regression curves associated to different cooling lubricating approaches.

\( \mathbf{cov}\boldsymbol{\upbeta } ={\hat{\upsigma}}^{\mathbf{2}}{\left({\mathbf{X}}^{\prime}\mathbf{X}\right)}^{-\mathbf{1}} \) is the covariance matrix, \( {\hat{\upsigma}}^{\mathbf{2}}=S{S}_E/\left(n-p\right) \), where p is the number of regression coefficients and n is the number of the available TL data.

In order to statistically compare the model parameters (regression coefficients β0 and β1) identified in different CL conditions, a supplementary ANOVA that jointly analyzed the data was carried out as suggested by Clogg et al. in [27]. According to the specific literature, this approach is preferable than the 2t test (Montgomery, [26]) that tends to refuse more frequently the null hypothesis due to the fact that the regression coefficients are coming from the same set of covariates. Specifically, the additional ANOVA was carried out defining a categorial variable named CL type (that could be cryogenic or conventional). The proposed analysis considered, as additional contribution to the model, both the categorial variable and the interaction term ln vc* CL type. Considerations on the achieved results, according to the selected end-of-life criterion, were reported.

3.1.1 Small cutting time criterion—average flank width

Taylor’s regression was carried out considering the first dataset of TLi, obtained using VBt=0.2 as the end-of-life criterion. The regression curves (cryogenic/conventional cutting), their 95% CIs, and the experimental data are reported in Fig. 7.

The corresponding ANOVA of the regression is presented in Tables 6 and 7 while the estimated regression coefficients are summarized in Tables 8 and 9 together with the associated SE that can be used to estimate the 95% CIs of the estimated model parameters, Eq. 9 (see Fig. 8 and Fig. 9).

It seems that the both the regression coefficients only slightly differ. As anticipated at the beginning of this section, in order to statistically compare both the model parameters (regression coefficients β0 and β1 identified in different CL conditions), a specific ANOVA was carried out, Table 10.

The results demonstrated (being the CL type and the interaction term P-values>α=0.05) that the null hypotheses \( {H}_{0-{\beta}_0-\mathrm{comparison}}:{\beta}_{0-\mathrm{cryo}}={\beta}_{0-\mathrm{conv}} \) and \( {H}_{1-{\beta}_1-\mathrm{comparison}}:{\beta}_{1-\mathrm{cryo}}={\beta}_{1-\mathrm{conv}} \)cannot be refused. This means that there is no statistical evidence to distinguish the two formulations. The coefficients of determination for both the regressions (R2 and R2adj) are summarized in Table 20.

3.1.2 Small cutting time criterion—maximum flank width

The analysis was carried out considering the criterion on the maximum flank width. The regression in the logarithmic coordinates was performed to identify the model parameters, reported in Tables 11 and 12. The corresponding ANOVAs are reported in Tables 13 and 14. The fitting curves for both cryogenic and conventional cutting (Fig. 10) together with their confidence intervals (CIs) are reported in Table 10.

Even in this case, the CIs for the identified model parameters were computed and are reported in Figs. 11 and 12.

The same approach (ANOVA on the overall data) was used to compare the regression coefficients even considering this end-of-life criterion. For the sake of brevity, the full ANOVA table was not reported but in this case both\( {H}_{0-{\beta}_0-\mathrm{comparison}} \) and \( {H}_{0-{\beta}_1-\mathrm{comparison}} \) can be refused. More specifically, it is worth noting that β0 − cryo < β1 − conv and β1 − cryo < β1 − conv. The same consideration can be inferred looking at Figs. 11 and 12. The analysis shows that for low cutting speeds, the expected tool duration is higher using conventional lubricant while in cryogenic cutting the increment of the cutting speed is not so detrimental as the one observed in conventional cutting.

3.1.3 Medium cutting time criterion—average wear width

The approach was extended to VBt=0.3 mm that is supposed to be a medium cutting time according to ISO 8688-1 [24]. The regression curves are reported in Fig. 13. The ANOVA results are reported in Tables 15 and 16. Although the P-value of the lack of fit (conventional cutting) is quite low, the R2 and R2adj are similar to the ones observed for the other regression models, Table 20.

The regression coefficients are summarized in Tables 17 and 18.

Figures 14 and 15 show the confidence intervals of the regression coefficients.

As done in the previous cases, the joined ANOVA was used for assessing \( {H}_{0-{\beta}_0-\mathrm{comparison}} \) and \( {H}_{0-{\beta}_1-\mathrm{comparison}} \). As observed for VBt=0.2 mm, even in this case, it seems that for both β0 and β1 the null hypothesis cannot be refused even if a slight trend (in accordance with what was observed for VBmt=0.7 mm) can be appreciated, see Figs. 14 and 15. In order to corroborate this evidence, a 2t test was performed. As anticipated, since the 2t test is generally more prone to refuse H0 especially if the coefficients come from the same set of covariates, we expected that the test is more sensitive to small variations in the parameter means. This was confirmed since the 2 t-test allowed refusing both the null hypotheses.

3.2 Results discussion

According to the presented regressions, Eqs. 4 and 5 were used to compute the Taylor’s coefficients (C and n).

Considering the performed analyses (resumed in Table 19), it can be noted that the effect of cryogenic cooling is statistically relevant only if the used end-of-life criterion is VBmtrefert to Table 19. This agrees with the shape of the flank wear lands reported in Table 5. Indeed, the average processing of the flank width (Eq. 1) tends to weaken the effects of the cooling lubricating strategy that seem to be irrelevant if VBt=0.2 mm was set while they start to be noticeable if the cutting time was extended (VBt=0.3 mm) although they did not result significant from the statistical perspective.

Since all the coefficients of determination seem comparable (Table 20) in all the regression, the cutting velocity explains roughly in the same manner the variability of the response variable TL.

The reported analyses confirmed that cryogenic cooling seems more effective than lubricant (oil-water emulsion) if high cutting speeds are used while for low cutting speeds (the ones typically used in industrial applications 50–70 m/min) conventional cooling remains the best alternative.

The same conclusion is in agreement with other research works but referring to turning process, [10, 13]. On the contrary, the results in milling operation are rather scattered and typically they are not properly analyzed.

This evidence was even confirmed by the analysis of the wear land reported in Table 5: at low cutting speeds, an adhesion phenomenon is clearly visible (assimilable to the built-up edge that typically occurs when the set cutting speed is too low). This phenomenology tends to decrease at higher velocity. It can be concluded that cryogenic cooling seems very promising, with respect to conventional cooling, in high-speed Ti6Al4v cutting. This cooling technology would assure enhancing the cutting performance (increasing the material removal rate through cutting velocity increment) without a detrimental effect on the life of the tool. For instance, according to the engagement conditions reported in Table 2, at 125 m/min, the tool averagely lasted more than 15 min that is reasonable even from the industrial perspective (Table 21).

4 Conclusions

In this research, a comprehensive comparison in terms of tool life among conventional cooling and cryogenic (liquid nitrogen LN) in high feed milling was carried out. Several tests at different cutting velocities (three levels) were performed. The gathered data were used to identify Taylor’s law coefficients. The worn inserts were analyzed to make some considerations about the main wear mechanisms in all the tested conditions. It was found that:

-

Conventional cooling assures higher tool duration at low cutting speeds. The flank wear is regular.

-

In cryogenic cooling, adhesion-like phenomenon can be observed. This probably causes a chipping effect especially at low cutting velocity.

-

At high cutting velocity, the tool durations are more similar. Moreover, the identified models show that at higher velocities it is expected better performance for the cryogenic cooling approach. This duration can even be feasible for the shop floor scenario (time to change the tool).

Future research would be oriented to the consolidation of the findings of this preliminary work.

Availability of data and materials

Data are not available since the project was developed in collaboration with a company.

References

Abdelrazek AH, Choudhury IA, Nukman Y, Kazi SN (2020) Metal cutting lubricants and cutting tools: a review on the performance improvement and sustainability assessment. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 106:4221–4245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-019-04890-w

Jawahir IS, Attia H, Biermann D, Duflou J, Klocke F, Meyer D, Newman ST, Pusavec F, Putz M, Rech J, Schulze V, Umbrello D (2016) Cryogenic manufacturing processes. CIRP Ann - Manuf Technol 65:713–736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cirp.2016.06.007

Shokrani A, Dhokia V, Muñoz-Escalona P, Newman ST (2013) State-of-the-art cryogenic machining and processing. Int J Comput Integr Manuf 26:616–648. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951192X.2012.749531

Adler DP, Hii WW-S, Michalek DJ, Sutherland JW (2006) Examining the role of cutting fluids in machining and efforts to address associated in machining to address associated environmental/health concerns. Mach Sci Technol 10:23–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/10910340500534282

Hong SY (2019) Economical and ecological cryogenic machining. 123:331–338. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.1315297

Albertelli P, Monno M (2021) Energy assessment of different cooling technologies in Ti-6Al-4V milling. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 112:3279–3306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-020-06575-1

Rotella G, Dillon OW, Umbrello D et al (2014) The effects of cooling conditions on surface integrity in machining of Ti6Al4V alloy. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 71:47–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-013-5477-9

Balaji V, Ravi S, Chandran PN, Damodaran KM (2015) Review of the cryogenic machining in turning and milling process. Int J Res Eng Technol 04:38–42

Tahmasebi E, Albertelli P, Lucchini T, Monno M, Mussi V (2019) CFD and experimental analysis of the coolant flow in cryogenic milling. Int J Mach Tools Manuf 140:20–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJMACHTOOLS.2019.02.003

Wang ZY, Rajurkar KP (2000) Cryogenic machining of hard-to-cut materials. Wear 239:168–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0043-1648(99)00361-0

Hong SY, Ding Y, Jeong W (2001) Friction and cutting forces in cryogenic machining of Ti–6Al–4V. Int J Mach Tools Manuf 41:2271–2285. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0890-6955(01)00029-3

Sivaiah P, Chakradhar D (2017) Influence of cryogenic coolant on turning performance characteristics: a comparison with wet machining. Mater Manuf Process 32:1475–1485. https://doi.org/10.1080/10426914.2016.1269920

Strano M, Chiappini E, Tirelli S, Albertelli P, Monno M (2013) Comparison of Ti6Al4V machining forces and tool life for cryogenic versus conventional cooling. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part B J Eng Manuf 227:1403–1408. https://doi.org/10.1177/0954405413486635

Jun SC (2005) Lubrication effect of liquid nitrogen in cryogenic machining friction on the tool-chip interface. J Mech Sci Technol 19:936–946. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02919176

Bajpai V, Lee I, Park HW (2015) FE simulation of cryogenic assisted machining of Ti alloy (Ti6AI4V). In: Volume 1: Processing. ASME, p V001T02A028

Shi B, Elsayed A, Damir A, Attia H, M'Saoubi R (2019) A hybrid modeling approach for characterization and simulation of cryogenic machining of Ti-6Al-4V Alloy. J Manuf Sci Eng Trans ASME 141. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4042307

Davoudinejad A, Chiappini E, Tirelli S, Annoni M, Strano M (2015) FE simulation and validation of chip formation and cutting forces in dry and cryogenic cutting of Ti – 6Al – 4V. Procedia Manuf 1:728–739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2015.09.037

Sadik MI, Isakson S, Malakizadi A, Nyborg L (2016) Influence of coolant flow rate on tool life and wear development in cryogenic and wet milling of Ti-6Al-4V. Procedia CIRP 46:91–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2016.02.014

Pereira O, Urbikain G, Rodríguez A, Fernández-Valdivielso A, Calleja A, Ayesta I, de Lacalle LNL (2017) Internal cryolubrication approach for Inconel 718 milling. Procedia Manuf 13:89–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PROMFG.2017.09.013

Lu T, Kudaravalli R, Georgiou G (2018) Cryogenic machining through the spindle and tool for improved machining process performance and sustainability: Pt. II, Sustainability Performance Study. Procedia Manuf 21:273–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PROMFG.2018.02.121

Lu T, Kudaravalli R, Georgiou G (2018) Cryogenic machining through the spindle and tool for improved machining process performance and sustainability: Pt. I, System Design. Procedia Manuf 21:266–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2018.02.120

Pittalà GM (2018) A study of the effect of CO2 cryogenic coolant in end milling of Ti-6Al-4 V. Procedia CIRP 77:445–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PROCIR.2018.08.278

Jacso A, Matyasi G, Szalay T (2019) The fast constant engagement offsetting method for generating milling tool paths. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 103:4293–4305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-019-03834-8

International Standards (1994) ISO 8688: tool life testing in milling - part 1 : face milling. 1–28

International Standards (1993) ISO 3685: tool-life testing with single-point turning tools. 1–48

Montgomery D (2001) Design and analysis of experiments, 5th edn. John Wiley adn Sons

Clogg CC, Petkova E, Haritou A (1995) Statistical methods for comparing regression coefficients between models. Am J Sociol 100:1261–1293

Acknowledgements

This research was developed in the framework of the project “Nuovo processo di asportazione di truciolo supportato da fluido criogenico per materiali aeronautici di difficile lavorabilità: incremento della produttività, riduzione dei costi ed eliminazione degli oli da taglio”. The project was founded by the “Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico.” The project involves an important Italian machine tool manufacturer, Jobs Spa (FFG group). The authors would like to thank all the company staff that collaborated to the project development. Moreover, the authors would like to thank the SIAD company for the LN delivery and for the collaboration on the cryogenic plant enhancement and MMC Italia Srl (Mitsubishi Materials) for the tool and the inserts.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Politecnico di Milano within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. Partial financial support was received from Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico, Italy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Paolo Albertelli conceived the research, performed the tests, made the analysis, wrote the paper, and revised the paper. Valerio Mussi: performed the tests; Matteo Strano: carried out the proof-reading; Michele Monno carried out the proof-reading.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This research follows ethical standards

Consent to participate

The authors agree.

Consent for publication

The authors consent for publication.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Albertelli, P., Mussi, V., Strano, M. et al. Experimental investigation of the effects of cryogenic cooling on tool life in Ti6Al4V milling. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 117, 2149–2161 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-021-07161-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-021-07161-9