Abstract

This paper examines the effects of female education on marriage outcomes by exploiting the exogenous variation generated by the Female Secondary School Stipend Program in Bangladesh, which made secondary education free for rural girls. Our findings show that an additional year of female education leads to an increase in 0.72 years of husband’s education and that better educated women pair with spouses who have better occupations and are closer in age to their own, suggesting assortative mating. Those educated women appear to experience greater autonomy in making decisions on receiving their own health care and visiting their family. Furthermore, educated women have lower fertility and use more maternal health care, and their children have better health outcomes than those of less-educated women. Overall, our results suggest that the marriage market is one of the channels through which women’s education affects their life outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Boulier and Rosenzweig (1984) and Fafchamps and Quisumbing (2005) examine the positive assortative matching in rural Ethiopia and in the Philippines, respectively. Boulier and Rosenzweig (1984) use father’s education, female unemployment rate, and infant mortality as instruments for female education. Fafchamps and Quisumbing (2005) examine the correlations between characteristics of husbands and wives at the time of marriage.

Source: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics and UNICEF Bangladesh 2014.

Gross enrolment rate is the ratio of total enrolment, regardless of age, to the total population of the age group that officially corresponds to the level of education. Source: United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Institute for Statistics.

Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

Source: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, 2012b.

The exclusion restriction requires that the stipend program affect marriage outcomes only through women’s education. We believe that the program satisfies the exclusion restriction for an instrumental variable for the following reasons. First, the proposal for the Female Secondary School Assistance Project (World Bank Report No. P-5945-BD, source: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/512471468200338698/pdf/multi-page.pdf) states that the main objective of the project was to increase the pool of educated women who can participate in further development of the country. In addition, the vast majority of the total project cost (about 88% of the total cost excluding the cost for implementation and monitoring) was directly related to education, such as the stipend program (70%) and a teacher enhancement program and a female education awareness program (18%).

Subscripts indicating survey year and geographic area are omitted for simplicity.

We do not have information where they had lived during their secondary school years. The internal migration rate in Bangladesh, however, is quite low. The migration rate from rural to urban areas was 4.29 whereas in the other direction, the rate was 0.36% (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, 2012a). The low urban-to-rural migration rate indicates that to the extent that urban women in our data in fact participated in the stipend program, our first-stage results are likely to show the lower bound of possible effects of the program on education.

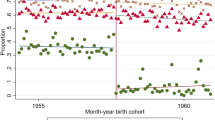

Students in grade 7 in 1994 and students in grade 8 in 1995 did not receive a stipend, but they received it for 2 consecutive years in 1996 and 1997 (in grades 9 and 10). Students in grade 8 in 1994 did not receive a stipend but received it for 2 years in 1995 and 1996 (in grades 9 and 10). Students in grade 9 in 1994 received a stipend for 2 years in 1994 and 1995.

As a further check, we provide a falsification test using only non-eligible cohorts (i.e., those who were born between 1965 and 1978) in Table 9. Placebo cohort 1 is those born between 1973 and 1978, while placebo cohort 2 is those born between 1970 and 1972; they are meant to resemble the structure of our original cohort 1 and cohort 2. Using these non-eligible cohorts, we find no significant coefficients on the interaction of placebo cohorts and a rural dummy, and if anything, the coefficient estimates are negative.

In the 2007 DHS, there are 134 urban areas and 227 the rural areas, while in the 2011 and 2014 DHS, there are 207 urban areas and 393 the rural areas.

The informal sector includes semi-skilled labor such as rickshaw drivers, carpenters, domestic servants, and factory workers, while the formal sector includes skilled employment including doctors, lawyers, accountants, entrepreneurs, traders, religious leaders, and factory workers who are skilled and trained.

The statistics look similar when we keep all children under age 5.

Our sample is restricted to married women, and if educated women tend to marry later, younger women, in particular, in the 2007 data, might drop out of the sample. Thus, our results might underestimate the effects of education by excluding young girls. Given that 97% of women in our sample married before they turned 23, if we use the 2011 and 2014 data only, most women (aged 23 to 43) in the sample had already married, and thus, we can partially address the sample selection issue. When we use the 2011 and 2014 data, the results do not change significantly.

Although not reported, we find no statistically significant effect of education on (1) whether a woman can go out without telling her husband, (2) whether a beating is justified if the wife argues with her husband, or (3) whether a beating is justified if the wife refuses to have sex.

The results do not change much when we include all children under age 5 (which increases the sample size about 20%) instead of including only the oldest child under age 5. The effect on height, however, decreases slightly and is no longer statistically significant at the 10% level (p value = 0.17) when the sample of all children under 5 years old is used.

Our estimates are lower than those of Güneş (2015). Note that the estimates of Güneş (2015) are based on the effect of primary schooling completion. In developing countries, returns to education are highest for primary education and the returns decline by the level of schooling (Colclough 1982; Psacharopoulos 1985, 1994; Schultz 1988).

Using randomized control trials in Rwanda, however, Okeke and Chari (2015) show that without addressing supply-side constraints (e.g., quality of service delivery), program-induced increases in the rate of institutional delivery do not necessarily reduce the newborn mortality.

References

Ahmed S, Creanga AA, Gillespie DG, Tsui AO (2010) Economic status, education and empowerment: implications for maternal health service utilization in developing countries. PLoS One 5(6). https://doi.org/10.1371/ journal. pone.0011190

Anderberg D, Zhu Y (2014) What a difference a term makes: the effect of educational attainment on marital outcomes in the UK. J Popul Econ 27(2):387–419

Asadullah MN, Chaudhury N (2009) Reverse gender gap in schooling in Bangladesh: insights from urban and rural households. J Dev Stud 45(8):1360–1380

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Statistics and informatics Division, Ministry of Planning, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh 2012a Population and Housing Census, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Statistics and informatics Division, Ministry of Planning, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh 2012b Statistical Yearbook of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics and UNICEF Bangladesh (2014) Bangladesh Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2012–2013. Progotir Pathey Final Report, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Behrman JR, Rosenzweig MR (2002) Does increasing women’s schooling raise the schooling of the next generation? Am Econ Rev 92(1):323–334

Boulier BL, Rosenzweig MR (1984) Schooling, search, and spouse selection: testing economic theories of marriage and household behavior. J Polit Econ 92(4):712–732

Breierova L, Duflo E 2004 The impact of education on fertility and child mortality: do fathers really matter less than mothers? National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper no. 10513, Cambridge, MA

Chen Y, Li H (2009) Mother’s education and child health: is there a nurturing effect? J Health Econ 28(2):413–426

Chiappori PA, Iyigun M, Weiss Y (2009) Investment in schooling and the marriage market. Am Econ Rev 99(5):1689–1713

Chong A, Cohen I, Field E, Nakasone E, Torero M (2016) Iron deficiency and schooling attainment in Peru. Am Econ J: Appl Econ 8(4):222–255

Chowdhury S, Mallick D, Chowdhury PR (2017) Natural shocks and marriage markets: evolution of mehr and dowry in Muslim marriages. IZA Discussion Paper no. 10675, Institute for the Study of Labor

Colclough C (1982) The impact of primary schooling on economic development: a review of the evidence. World Dev 10(3):167–185

Currie J, Moretti E (2003) Mother’s education and the intergenerational transmission of human capital: evidence from college openings. Q J Econ 118(4):1495–1532

Darmstadt GL, Lee AC, Cousens S, Sibley L, Bhutta ZA, Donnay F, Osrin D, Bang A, Kumar V, Wall SN, Baqui A, Lawn JE (2009) 60 million non-facility births: who can deliver in community settings to reduce intrapartum-related deaths? Int J Gynecol Obstet 107:S89–S112

Duflo E, Dupas P, Kremer M (2015) Education, HIV, and early fertility: experimental evidence from Kenya. Am Econ Rev 105(9):2257–2297

Fafchamps M, Quisumbing AR (2005) Marriage, bequest, and assortative matching in rural Ethiopia. Econ Dev Cult Chang 53(2):347–380

Fafchamps M, Quisumbing AR (2008) Household formation and marriage markets in rural areas. Handb Dev Econ 4:3187–3247

Fernandez R, Guner N, Knowles J (2005) Love and money: inequality, education, and marital sorting. Q J Econ 120(1):273–344

Field E, Ambrus A (2008) Early marriage, age of menarche, and female schooling attainment in Bangladesh. J Polit Econ 116(5):881–930

Filippi V, Ronsmans C, Campbell OM, Graham WJ, Mills A, Borghi J, Koblinsky M, Osrin D (2006) Maternal health in poor countries: the broader context and a call for action. Lancet 368(9546):1535–1541

Foster A, Khan N (2000) Equilibrating the marriage market in a rapidly growing population: evidence from rural Bangladesh. Univ. Pennsylvania Working Paper no. 80, Philadelphia, PA

Grépin KA, Bharadwaj P (2015) Maternal education and child mortality in Zimbabwe. J Health Econ 44:97–117

Güneş PM (2015) The role of maternal education in child health: evidence from a compulsory schooling law. Econ Educ Rev 47:1–16

Hahn Y, Islam A, Nuzhat K, Smyth R, Yang HS (2015) Education, marriage and fertility: long-term evidence from a female stipend program in Bangladesh. Research Discussion Paper no. 30–15, Monash Univ. Melbourne

Kamal N (2000) The influence of husbands on contraceptive use by Bangladeshi women. Health Policy Plan 15(1):43–51

Khandker S, Pitt M, Fuwa N (2003) Subsidy to promote girls’ secondary education: the female stipend program in Bangladesh. World Bank, Washington, DC

Lavy V, Zablotsky A (2011) Mother’s schooling and fertility under low female labor force participation: evidence from a natural experiment. NBER Working Paper No.16856, Cambridge, MA

Lefgren L, McIntyre F (2006) The relationship between women’s education and marriage outcomes. J Labor Econ 24(4):787–830

Lewis SK, Oppenheimer VK (2000) Educational assortative mating across marriage markets: Nonhispanic Whites in the United States. Demography 37(1):29–40

Lochner L (2011) Non-production benefits of education: crime, health, and good citizenship. NBER Working Paper No. 16722, Cambridge, MA

Maitra P (2004) Parental bargaining, health inputs and child mortality in India. J Health Econ 23(2):259–291

Mansour H, McKinnish T (2014) Who marries differently aged spouses? Ability, education, occupation, earnings, and appearance. Rev Econ Stat 96(3):577–580

Mare RD (1991) Five decades of educational assortative mating. Am Sociol Rev 56(1):15–32

McCrary J, Royer H (2011) The effect of female education on fertility and infant health: evidence from school entry policies using exact date of birth. Am Econ Rev 101(1):158–195

Nielsen HS, Svarer M (2009) Educational homogamy how much is opportunities? J Hum Resour 44(4):1066–1086

Okeke E, Chari AV (2015) Can institutional deliveries reduce newborn mortality? RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA

Osili UO, Long BT (2008) Does female schooling reduce fertility? Evidence from Nigeria. J Dev Econ 87(1):57–75

Pal S (2015) Impact of hospital delivery on child mortality: an analysis of adolescent mothers in Bangladesh. Soc Sci Med 143:194–203

Pencavel J (1998) Assortative mating by schooling and the work behavior of wives and husbands. Am Econ Rev 88(2):326–329

Psacharopoulos G (1985) Returns to education: a further international update and implications. J Hum Resour 20(4):583–604

Psacharopoulos G (1994) Returns to investment in education: a global update. World Dev 22(9):1325–1343

Rosenzweig MR, Schultz TP (1989) Schooling, information and nonmarket productivity: contraceptive use and its effectiveness. Int Econ Rev 30(2):457–477

Schultz TP (1988) Education investments and returns. Handb Dev Econ 1:543–630

Thomas D, Strauss J, Henriques MH (1991) How does mother’s education affect child height? J Hum Resour 26(2):183–211

UNICEF Bangladesh 2009 Report on quality primary education. Dhaka

Weiss Y, Willis RJ (1997) Match quality, new information, and marital dissolution. J Labor Econ 15(1):S293–S329

World Bank (2003) Project Performance Assessment Report Bangladesh Female Secondary School Assistance Project. Credit 2649, Report no. 26226. World Bank, Washington, DC

Acknowledgements

We thank Julie Cullen, Asadul Islam, Booyuel Kim, Do Won Kwak, Pushkar Maitra, Debdulal Mallick, Russell Smyth, Haishan Yuan, the editor, and two anonymous referees, as well as seminar participants at Monash University, University of Queensland, Korea Development Institute, Chung-Ang University, and the 2016 Korea Economic Association Conference for helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Junsen Zhang

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hahn, Y., Nuzhat, K. & Yang, HS. The effect of female education on marital matches and child health in Bangladesh. J Popul Econ 31, 915–936 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-017-0673-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-017-0673-9

Keywords

- Female education

- School stipend program

- Assortative mating

- Spouse characteristics

- Child health

- Bangladesh