Abstract

Exploiting the exogenous variation in user fees caused by a Swedish childcare reform, we are able to identify the causal effect of childcare costs on fertility in a context in which childcare enrollment is almost universal, user fees are low, and labor force participation of mothers is very high. Anticipation of a reduction in childcare costs increased the number of first and higher-order births, but only seemed to affect the timing of second births. For families with many children we also find a marginally significant negative income effect on fertility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See also Hirazawa and Yakita (2009) for a theoretical model where they analyze the long-run effects of a pay-as-you-go social security system on fertility.

Note that even though maternal labor force participation is high in Sweden, many mothers with small children work part-time, Hence, there was a potential for an increased labor supply.

Publicly subsidized childcare comes in different forms, the most common being center-based care. Different forms of family daycare—e.g., care provided in a publicly paid caretaker’s home or in the child’s home—also exist, although to a rather small extent (in 2001, only 5% of all enrolled children had this type of care). Although the financing of childcare is public, care providers can be public, cooperative, or private. Until the early 1990s, childcare was almost exclusively publicly provided; since then, a growing proportion of municipalities have introduced voucher systems, paving the way for the private provision of services. These private childcare centers still have to follow the nationally set curriculum.

There are 290 local governments in Sweden. In addition to arranging childcare, they are responsible for primary and secondary education, care of the elderly and disabled, welfare, and local infrastructure. Local governments finance their activities through (in order of their importance) a proportional local income tax, grants from the central government, and user fees.

Infants are instead cared for by their parents. Parents are entitled to a year’s paid parental leave with an earnings replacement rate of 80% up to a cap.

The father’s work hours has a much smaller impact on attendance time. Men are also much less likely to work part-time (Skolverket 2007).

Also differences in income due to differences in the tax base are principally equalized across municipalities.

Elinder et al. (2008) analyze the reform’s impact on voter behavior and find that families with young children increased their propensity to vote for the incumbent government.

The reform also introduced a right for children whose parents were unemployed or on parental leave to attend childcare for a minimum of 15 h per week.

These municipalities are not included in the study.

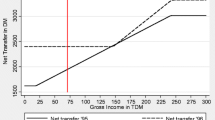

The percentage rate for the first child in preschool is 3%; the rate is 2% for the second child, and 1% for the third child. The corresponding figures for after-school care are 2%, 1%, and 1%. The household does not pay anything for child number 4 or for any children thereafter. The youngest child is defined as child number 1. Hence, families with one child in preschool and one in after-school care pay 4% of household income.

Calculated for currency rates on November 2, 2011.

Total fertility in a given year shows how many children a hypothetical woman would have in her lifetime if she had as many children at each age as women of a given age in that particular year.

The variables that determine childcare charges are household income, the number of children, and the age of each child. These are all available in Swedish register data, and it is therefore possible to compute each household’s exact childcare fee both before and after the reform, on the assumption that all children of childcare-eligible age are enrolled in full-time childcare. We return to this issue in Section 3.4.

The reason that we compare household of the same type over time rather than to follow the same households over time is that the children in the households will be older after the reform than before and we believe that age of already born children is very likely to have a direct effect on the fertility behavior of mothers.

Elinder et al. (2008) show that the election promise was credible enough to affect families’ voting behavior.

Note that the model is estimated on first differences at the household type - municipal level which implies that any level effects are differenced out.

IFAU collected childcare fee data via an email request sent to all Swedish municipalities asking for exact formulas used to calculate prices in 2001–04. Information about the exact fee structure from 220 of Sweden’s 290 municipalities was received. Comparing the pre-reform childcare costs for a number of type families in the municipalities that responded with those of the municipalities that did not respond (available in Skolverket 1999), we conclude that the costs are very similar, which implies that we need not worry about selection based on a specific type of municipality.

We have tried to impute household income for these unmarried childless women using predictions from the sample for which we observe both parents. Because we were unable to replicate our results for the married women using predicted household income, we judge that the results for unmarried childless women are too speculative and uncertain.

Note that we do not observe whether children attend childcare or for how many hours they do so. The cost measure we calculate is based on the assumption that everyone attends childcare and after-school care full-time. As a sensitivity test, we will also calculate the costs assuming that children do not attend after-school care. We have further assumed that the families discount future costs exponentially with the discount rate 0.05. Within reasonable limits, the results are not sensitive to the choice of discount factor.

The information collected by IFAU pertains to the fee schedules as they were in 2001. Information on prices scheduled prior to 2001 is not available, but the survey information suggests that there were no major changes in local fee schedules in the years prior to the reform. As a result, we use the fee schedule for 2001 to compute what the household pre-reform fee was in the years prior to 2001. Although inflation was minor during these years, we have denominated household incomes in 2001 prices using a consumer price index in order to achieve comparability across years.

This sample only includes married couples, since register data does not allow us to capture cohabiting couples without common children.

We have also elaborated with a linear household-type trend, and a linear municipality trend respectively. Doing this, we still find an effect the first year, and we therefore reject those specifications. These results are available upon request.

The median share of votes for the Social Democrats in the 1998 election was 38%.

References

Adsera A (2004) Changing fertility rates in developed countries. The impact of labor market institutions. J Popul Econ 17(1):17–43

Adsera A (2005) Vanishing children: from high unemployment to low fertility in developed countries. Am Econ Rev 95(2):189–193

Angrist J, Lavy V, Schlosser A (2010) Multiple experiments for the causal link between the quantity and quality of children. J Labor Econ 28(4):773-824

Apps P, Rees R (2004) Fertility, female labor supply and public policy. Scandinavian J Econ 106(4):745–763

Björklund A (2006) Does family policy affect fertility? J Popul Econ 19(1):3–24

Blau DM, Robins PK (1989) Fertility, employment, and child-care costs. Demography 26(2):287–299

Brewer M, Ratcliffe A, Smith S (2010) Does welfare reform affect fertility? Evidence from the UK. J Popul Econ. doi:10.1007/s00148-010-0332-x

Cohen A, Dehejia R, Romanov D (2009) Do financial incentives affect fertility? NBER Working Paper 13700

Cortes P, Tessada J (2011) Low-skilled immigration and the labor supply of highly skilled women. Am Econ J: Appl Econ 3(3):88–123

D’Addio AC, d’Ercole M (2005) Trends and determinants of fertility rates in OECD countries: the role of policies. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Paper No 27

Del Boca D (2002) The effect of child care and part time opportunities on participation and fertility decisions in Italy. J Popul Econ 15(3):549–573

Elinder M, Jordahl H, Poutvara P (2008) Selfish and prospective: theory and evidence of pocketbook voting. CESifo Working paper No 2489

Ermisch JF (1989) Purchased child care, optimal family size and mother’s employment. J Popul Econ 2(2):79–102

Furtado D, Hock H (2010) Immigrant labor, child-care services, and the work-fertility trade-off in the United States. Am Econ Rev 100(2):22–228

Hirazawa M, Yakita A (2009) Fertility, child care outside the home, and pay-as-you-go social security. J Popul Econ 22(3):565–583

Kearney M (2004) Is there an effect of incremental welfare benefits on fertility behavior? A look at the family cap. J Hum Resour 39(2):295–325

Laroque G, Salanié B (2004) Fertility and financial incentives in France. CESifo Econ Stud 50(3):423–450

Lundin D, Mörk E, Öckert B (2008) How far can reduced childcare prices push female labour supply? Labour Economics 15(4):647–659

Milligan K (2005) Subsidizing the stork: new evidence on tax incentives and fertility. Rev Econ Stat 87(3):539–555

Moffit R (2005) Remarks on the analysis of causal relationships in population research. Demography 42(1):91–108

OECD (2005) Babies and bosses: reconciling work and family life? Canada, Finland, Sweden and the United Kingdom

Schlosser A (2006) Public preschool and the labor supply of Arab mothers: evidence from a natural experiment. Mimeo Hebrew University, Jerusalem

Skolverket (1999) Avgifter i förskola och fritidshem 1999. Rapport 174

Skolverket (2003) Avgifter i förskola och fritidshem. Fördjupning av rapport 231

Skolverket (2007) Barns omsorg. Tillgång och efterfrågan på barnomsorg för barn 1–12 år med olika social bakgrund. Rapport 203

Smith J, Todd P (2005) Does matching overcome LaLonde’s critique of nonexperimental estimators? J Econom 125(1–2):305–353

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for comments by two anonymous referees as well as from Matz Dahlberg, Peter Fredriksson, Christian Holzner, Rafael Lalive, Imran Rasul, and participants at seminars at IFN, IFAU, SOFI, Stockholm University, Växjö University, the IFN Stockholm Conference on Family, Children and Work and the 23rd Annual Congress of EEA in Milan, SOLE 2009, the ELE Summer Institute, Bergen 2009, the Econometric Society’s 2009 North American Summer Meeting in Boston, the 2009 NBER Summer Institute, the 2009 IIPF Congress in Cape Town, and the 2010 ASSA Meeting in Atlanta. Financial support from Riksbankens Jubileumsfond is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Junsen Zhang

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mörk, E., Sjögren, A. & Svaleryd, H. Childcare costs and the demand for children—evidence from a nationwide reform. J Popul Econ 26, 33–65 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-011-0399-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-011-0399-z