Abstract

Complementing prior research on income and educational mobility, we examine the intergenerational transmission of cognitive abilities. We find that individuals’ cognitive skills are positively related to their parents’ abilities, despite controlling for educational attainment and family background. Differentiating between mothers’ and fathers’ IQ transmission, we find different effects on the cognition of sons and daughters. Cognitive skills that are based on past learning are more strongly transmitted between generations than skills that are related to innate abilities. Our findings are not compatible with a pure genetic model but rather point to the importance of parental investments for children’s cognitive outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Bowles and Gintis (2002: 12) note that “for the commonly used Armed Forces Qualification Test (AFQT), for example—a test used to predict vocational success that is often used as a measure of cognitive skills—the correlation between two test scores taken on successive days by the same person is likely to be higher than the correlation between the same person’s reported years of schooling or income on two successive days.”

We do not neglect that the individual’s environments, including peers, grandparents, and neighborhood, may also play a role in the development of cognitive and non-cognitive abilities. However, it is plausible to assume that the two channels mentioned mainly affect the critical early life-cycle cognitive development.

According to this framework, the technology varies with the periods of development. In the first stages, the primary care givers (in most cases the individual’s parents) form the environment in which initial conditions, i.e., the individual’s abilities endowment, can thrive. In later stages, there is interaction with parents, the larger family, with friends and in school that affects individuals’ abilities and how these evolve.

Research in neuroscience however emphasizes that genes are the predominant determinant of IQ transmission (e.g., Toga and Thompson 2005).

Another strand of literature combines the analysis of income mobility with cognitive skills. Bowles and Gintis (2002) identify cognitive abilities as one of the causal channels of intergenerational transmission of economic status. Blanden et al. (2007) show that parental income is strongly associated with children’s cognitive abilities, which in turn significantly affect their earnings later in life. By comparing earnings correlations of parents with biological children and those with adopted children, Liu and Zeng (2009) reveal the importance of genetic ability for the intergenerational transmission of earnings in the USA.

Matching parents’ information to their children is possible for (grown up) children who lived at some point of time during the survey years (1984–2006) in the same household as the parents. Only then are mother and father identifiers available. This requirement naturally excludes relatively old respondents from our sample, since these were less likely to be observed in the same household as their parents during the survey years (54% of the individuals in our sample live in the same household as their parents: 49% of females and 57% of males).

As usual in survey-based datasets, it is not possible in the SOEP to identify biological parents with full certainty. Available birth biographies for men and women allow identifying 70% of biological (or adoptive) fathers and 80% biological (or adoptive) mothers in our sample. The identification of the remaining parents was based on children files, which include pointers to the mother and to the partner of the mother, and on the relationship of the child to the head of the household. This implies that the probability of identifying non-biological parents is higher among these children due to the more frequent presence of stepparents or new partners of the biological parent who act as social parents. Additional regressions, in which we restrict our sample to children for whom biological (or adoptive) parents could be identified (n = 347), yield virtually the same results.

It might be argued that the time constraint of 90 s interferes with the concept of crystallized intelligence inasmuch as factors like working memory come into play. Working memory however is related to executive function and thus to fluid intelligence rather than crystallized intelligence only. It should therefore be kept it mind that the WFT scores may be a mixture of fluid and crystallized intelligence.

If at all, the random component to cognition test scores in our data may lead to a downward bias in the estimates of IQ correlations.

Age-standardized test scores are generated by calculating the scores’ standardized value for every year along the age distribution.

Note that the parents’ ability test scores have been age-standardized using all individuals with available test score information because there were too few persons in some of the age groups within the sample. The higher number of observations further allowed to age-standardize the test scores for males and females separately.

Although formal education in part depends on early cognitive ability, it has been shown that additional years of schooling increase IQ later in life (Falch and Sandgren 2010).

It is striking that there is only a minor difference between parents’ and children’s word fluency test scores. This is in line with the notion in psychology that crystallized intelligence remains fairly stable, whereas cognitive speed declines at old age.

We are grateful to one of the referees for pointing us to this method.

Pure correlations of age-standardized ability test scores between parents and their children are about 0.45 for the SCT and 0.46 for the WFT.

We cross-checked this result using the initial sample of 5,321 observations before merging the data to the respondents’ parents. Regressing the IQ test scores on gender and educational attainment for the larger sample yields only slightly higher R 2 values as compared to our final sample. This may seem unexpected at first glance, but note again that the tests aim at measuring individuals’ intelligence and not achievement. This might be behind this first low explained variation.

Adjusting the standard errors to account for heteroskedasticity and for intra-family correlation does not affect the results.

In order to compare these estimates with intergenerational transmission of educational attainment, educational degrees of parents and children are transformed into years of schooling. The transmission effect with respect to years of schooling, when only a gender dummy is included, amounts to 0.319 (SE, 0.046, adjusted R 2, 0.109). It slightly decreases to 0.277 (SE, 0.047, adjusted R 2, 0.160) when parental test scores are also taken into account. Detailed results are available from the authors upon request.

In three alternative specifications, we checked for differences between East and West Germany by including a dummy variable for (a) living in East Germany, (b) being born in the former GDR, (c) having spent the childhood (at least 10 years) in the former GDR. However, none of these variables were statistically significant, and the test score estimates were not affected.

As an additional robustness check, we included the disability status of the parents and an interaction term with parents’ test scores. Both main and interaction effects were negative for coding speed and positive for the word fluency test, but none of them was statistically significant. Parental test score coefficients however were not affected.

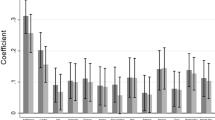

The differences between mothers’ and fathers’ transmission effects on children’s IQ scores were formally tested using Wald tests. The test statistics yielded hardly significant results. This may however be attributed to the small sample size and the related lack of precision. A statistically significant difference between mothers’ and fathers’ transmission effects at the 8% significance level was shown in the estimates of the SCT scores for the sub-sample of daughters. The remaining differences between coefficients should be interpreted with caution.

In order to test differences in the transmission effects between sons and daughters, we run additional regressions fully interacted with a gender dummy. Again, the small sample size decreases the chance that any interaction term with parental test scores is statistically significant. The interaction term for mothers’ test scores is not statistically different from zero in any specification. The only relevant gender difference in the fully interacted model was shown by the interaction term between gender and fathers’ SCT scores, which is positive and statistically significant at the 14% level, whereas the main effect vanishes completely.

This result does not change qualitatively when factorized data is used instead of averaging.

Moreover, there is evidence that not all types of cognitive abilities are equally economically important. The findings of Anger and Heineck (2010) suggest that coding speed is positively related to earnings, whereas verbal fluency is not.

References

Agee MD, Crocker TD (2002) Parents’ discount rate and the intergenerational transmission of cognitive skills. Economica 69(273):143–154

Anger S, Heineck G (2010) Cognitive abilities and earnings - first evidence for Germany. Appl Econ Lett (in press)

Björklund A, Jäntti M, Solon G (2007) Nature and nurture in the intergenerational transmission of socioeconomic status: evidence from Swedish children and their biological and rearing parents. BE J Econ Anal Policy 7(2), Article 4

Björklund A, Hederos Eriksson K, Jäntti M (2009) IQ and family background: are associations strong or weak? IZA Discussion Paper No. 4305

Black SE, Devereux PJ, Salvanes KG (2009) Like father, like son? A note on the intergenerational transmission of IQ scores. Econ Lett 105(1):138–140

Black SE, Devereux PJ, Salvanes KG (2010a) Older and wiser? Birth order and IQ of young men. Econ Lett (in press)

Black SE, Devereux PJ, Salvanes KG (2010b) Small family, smart family? The effect of family size on IQ. J Hum Resour (in press)

Blanden J, Gregg P, Macmillan L (2007) Accounting for intergenerational income persistence: noncognitive skills, ability and education. The Econ J 117(519):C43–C60

Bouchard TJ Jr, McGue M (1981) Familial studies of intelligence: a review. Science 212(4498):1055–1059

Bowles S, Gintis H (2002) The inheritance of inequality. J Econ Perspect 16(3):3–30

Bronars SG, Oettinger GS (2006) Estimates of the return to schooling and ability: evidence from sibling data. Labour Econ 13(1):19–34

Brown S, McIntosh S, Taylor K (2009) Following in your parents’ footsteps? Empirical analysis of matched parent–offspring test scores. IZA Discussion Paper No. 3986

Cameron S, Heckman JJ (1993) Nonequivalence of high school equivalents. J Labor Econ 11(1):1–47

Case A, Paxson C (2008) Stature and status: height, ability and labor market outcomes. J Polit Econ 116(3):499–532

Cattell RB (1987) Intelligence: its structure, growth, and action. Elsevier, New York

Cebi M (2007) Locus of control and human capital investment revisited. J Hum Resour 42(4):919–932

Corak M (2006) Do poor children become poor adults? Lessons from a cross country comparison of generational earnings mobility. In: Creedy J, Kalb G (eds) Dynamics of inequality and poverty, research on economic inequality. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 143–188

Cunha F, Heckman JJ (2007) The technology of skill formation. Am Econ Rev 97(2):31–47

Ermisch J (2008) Origins of social immobility and inequality: parenting and early child development. Natl Inst Econ Rev 205(1):62–71

Ermisch J, Francesconi M (2001) Family matters: impacts of family background on educational attainment. Economica 68(270):137–156

Falch T, Sandgren S (2010) The effect of education on cognitive ability. Econ Inq (in press)

Flynn JR (1994) IQ gains over time. In: Sternberg RJ (ed) Encyclopedia of human intelligence. Macmillan, New York, pp 617–623

Green DA, Riddell WC (2003) Literacy and earnings: an investigation of the interaction of cognitive and unobserved skills in earnings generation. Labour Econ 10(2):165–184

Groth-Marnat G (1997) Handbook of psychological assessment, 3rd edn. Wiley, New York

Hanushek EA, Woessmann L (2008) The role of cognitive skills in economic development. J Econ Lit 46(3):607–668

Heckman JJ, Stixrud J, Urzua S (2006) The effects of cognitive and noncognitive abilities on labor market outcomes and social behavior. J Labor Econ 24(3):411–482

Heckman JJ, Vytlacil E (2001) Identifying the role of cognitive ability in explaining the level of and change in the return to schooling. Rev Econ Stat 83(1):1–12

Heineck G (2009) Too tall to be smart? The relationship between height and cognitive abilities. Econ Lett 105(1):78–80

Heineck G, Riphahn RT (2009) Intergenerational transmission of educational attainment in Germany - the last five decades. Jahrb Natlökon Stat (J Econ Stat) 229(1):36–60

Heineck G, Anger S (2010) The returns to cognitive abilities and personality traits in Germany. Labour Econ (in press)

Hertz T, Jayasundera T, Piraino P, Selcuk S, Smith N, Verashchagina A (2007) The inheritance of educational inequality: international comparisons and fifty-year trends. J Econ Anal Policy 7(2), Article 10

Klepper S, Leamer EE (1984) Consistent sets of estimates for regressions with errors in all variables. Econometrica 52(1):163–183

Kline P (1999) The handbook of psychological testing. Routledge, New York

Lang FR, Weiss D, Stocker A, von Rosenbladt B (2007) Assessing cognitive capacities in computer-assisted survey research: two ultra-short tests of intellectual ability in the german socio-economic panel study. Schmollers Jahr 127(1):183–192

Leamer EE, Leonard HB (1983) Reporting the fragility of regression estimates. Rev Econ Stat 65(2):306–317

Lindenberger U, Baltes B (1995) Kognitive Leistungsfähigkeit im Alter: Erste Ergebnisse aus der Berliner Altersstudie. Zeitschrift für Psychologie 203(4):283–317

Liu H, Zeng J (2009) Genetic ability and intergenerational earnings mobility. J Popul Econ 22(1):75–95

Mueller G, Plug E (2006) Estimating the effects of personality on male and female earnings. Ind Labor Relat Rev 60(1):3–22

Nicoletti C, Ermisch JF (2007) Intergenerational earnings mobility: changes across cohorts in Britain. BE J Econ Anal Policy 7(2), Article 9

Oreopoulos P (2003) The long-run consequences of growing up in a poor neighbourhood. Q J Econ 118(4):1533–1575

Pfeiffer FT (2008) Persistent inequality in educational attainment and its institutional context. Eur Sociol Rev 24(5):543–565

Plug E, Vijverberg W (2003) Schooling, family background, and adoption: is it nature or is it nurture. J Polit Econ 111(3):611–641

Plomin R, Owen MJ, McGuffin P (1994) The genetic basis of complex human behaviors. Science 264(5166):1733–1739

Plomin R, DeFries JC, McClearn GE, McGuffin P (2000) Behavioral genetics, 4th edn. Freeman, New York

Sacerdote B (2002) The nature and nurture of economic outcomes. Am Econ Rev 92(2):344–348

Schupp J, Hermann S, Jaensch P, Lang FR (2008) Erfassung kognitiver Leistungspotentiale Erwachsener im Sozio-oekonomischen Panel (SOEP). Data Documentation 32, DIW Berlin

Shonkoff J, Phillips D (2000) From neurons to neighborhoods: the science of early childhood development. National Academy Press, Washington

Smith A (1995) Symbol digit modalities test. Western Psychological Services, Los Angeles

Solon G (2002) Cross-country differences in intergenerational earnings mobility. J Econ Perspect 16(3):59–66

Todd PE, Wolpin KI (2003) On the specification and estimation of the production function for cognitive achievement. Econ J 113(485):F3–F33

Toga AW, Thompson PM (2005) Genetics of brain structure and intelligence. Annu Rev Neurosci 28:1–23

Wagner GG, Frick JR, Schupp J (2007) The German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP)—scope evolution and enhancements. Schmollers Jahr 127(1):139–169

WHO (2007) Early child development: a powerful equalizer. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2007/a91213.pdf. Accessed November 13, 2009

Zimmerman DJ (1992) Regression toward mediocrity in economic stature. Am Econ Rev 82(3):409–429

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge helpful comments from Sandra Black, Michael Kvasnicka, Steve Machin, Regina Riphahn, Thomas Siedler, and Bernd Weber. We also would like to thank the editor and two anonymous referees for their valuable suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Deborah Cobb-Clark

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00148-010-0327-7

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Representativeness of the sample

The severe reduction in sample size (from a total number of 22,665 SOEP respondents in 2006 to 504 test participants with information on their parents’ test performance) raises the issue of representativeness of the data, as there might be selection problems with respect to (a) test participation and (b) availability of parent–child pairs. The first question is whether individuals who participated in the cognitive ability tests differ systematically from test deniers or from those respondents who were not asked to participate in the IQ tests, since they were not CAPI interviewed. Table 6 shows summary statistics of the variables used in the analysis for all SOEP respondents in 2006 by interview mode and test participation. Persons who refused to participate in the IQ test were, on average, somewhat older, had slightly lower education, were more often raised in rural areas, and had their residence more often in South Germany. These differences are statistically significant, but except for the regional discrepancies, the comparison of the sample means yields no overwhelming differences between groups. The same is true when test participants are compared to SOEP respondents who were interviewed with other than the CAPI interview mode and hence not asked to participate in the IQ tests. Compared to respondents with other interview modes, East Germans are underrepresented in the sample of test participants. We therefore have to keep in mind that our sample of IQ test participants might not be fully representative for all regions in Germany. However, we conclude that there are no severe selection problems due to test participation with respect to the central variables in our study.

The second question is whether individuals whose parents also participated in the IQ test can be compared to the rest of the population. Table 7 in the Appendix shows summary statistics of all variables used in the analysis for our sample compared to all other parent–child pairs with interviews in 2006. These include parent–child pairs who are not part of the sample because either the child or the parent had an interview mode other than CAPI or refused to participate in the IQ test. Individuals who were included in our sample of parent–child pairs with IQ test scores were on average two years younger and, related to that, slightly less educated, less experienced in the labor market, and fewer of them were married than individuals who belong to the excluded parent–child pairs. In our sample, a higher percentage of parents had no school degree, and again, persons from South and East Germany were underrepresented. Since most discrepancies are rather small and furthermore can be explained by the age difference between the two samples, we conclude that the selection of parent–child pairs with information on IQ test performance does not erode the representativeness of the data. To undermine this, we check whether the results are driven by relatively young sons and daughters in our sample. By restricting our sample to children aged 25 or older (222 observations; average age: 32.6 years), we obtain virtually the same results as for the full sample.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Anger, S., Heineck, G. Do smart parents raise smart children? The intergenerational transmission of cognitive abilities . J Popul Econ 23, 1105–1132 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-009-0298-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-009-0298-8